|

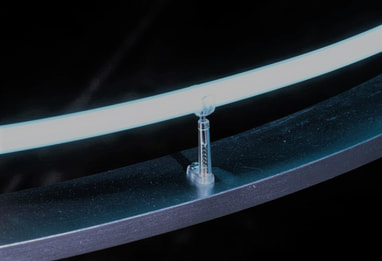

by Gilles Deleuze The body is the Figure, or rather the material of the Figure. The material of the Figure must not be confused with the spatializing material structure, which is positioned in opposition to it. The body is the Figure, not the structure. Conversely, the Figure, being a body, is not the face, and does not even have a face. It does have a head, because the head is an integral part of the body. It can even be reduced to the head. As a portraitist, Bacon is a painter of heads, not faces, and there is a great difference between the two. For the face is a structured, spatial organization that conceals the head, whereas the head is dependent upon the body, even if it is the point of the body, its culmination. It is not that the head lacks spirit; but it is a spirit in bodily form, a corporeal and vital breath, an animal spirit. It is the animal spirit of man: a pig-spirit, a buffalo-spirit, a dog-spirit, a bat-spirit .... Bacon thus pursues a very peculiar project as a portrait painter: to dismantle the face, to rediscover the head or make it emerge from beneath the face. The deformations which the body undergoes are also the animal traits of the head. This has nothing to do with a correspondence between animal forms and facial forms. In fact, the face lost its form by being subjected to the techniques of rubbing and brushing that disorganize it and make a head emerge in its place. And the marks or traits of animality are not animal forms, but rather the spirits that haunt the wiped off parts, that pull at the head, individualizing and qualifying the head without a face. Bacon's techniques of local scrubbing and asignifying traits take on a particular meaning here. Sometimes the human head is replaced by an animal; but it is not the animal as a form, but rather the animal as a trait - for example, the quivering trait of a bird spiraling over the scrubbed area, while the simulacra of portrait-faces on either side of it act as "attendants" (as in the 1976 Triptych). Sometimes an animal, for example a real dog, is treated as the shadow of its master or conversely, the man's shadow itself assumes an autonomous and indeterminate animal existence. The shadow escapes from the body like an animal we had been sheltering. In place of formal correspondences, what Bacon's painting constitutes is a zone of indiscernibility or undecidability between man and animal. Man becomes animal, but not without the animal becoming spirit at the same time, the spirit of man, the physical spirit of man presented in the mirror as Eumenides or Fate. It is never a combination of forms, but rather the common fact: the common fact of man and animal. Bacon pushes this to the point where even his most isolated Figure is already a coupled Figure; man is coupled with his animal in a latent bullfight. This objective zone of indiscernibility is the entire body, but the body insofar as it is flesh or meat. Of course, the body has bones as well, but bones are only its spatial structure. A distinction is often made between flesh and bone, and even between things related to them. The body is revealed only when it ceases to be supported by the bones, when the flesh ceases to cover the bones, when the two exist for each other, but each on its own terms: the bone as the material structure of the body, the flesh as the bodily material of the Figure. Bacon admires the young woman in Degas's After the Bath [101], whose suspended spinal column seems to protrude from her flesh, making it seem much more vulnerable and lithe, acrobatic.2 In a completely different context, Bacon has painted such a spinal column on a Figure doubled over in contortions (Three Figures and a Portrait, 1975 [78]). This pictorial tension between flesh and bone is something that must be achieved. And what achieves this tension in the painting is, precisely, meat, through the splendor of its colors. Meat is the state of the body in which flesh and bone confront each other locally rather than being composed structurally. The same is true of the mouth and the teeth, which are little bones. In meat, the flesh seems to descend from the bones, while the bones rise up from the flesh. This is a feature of Bacon that distinguishes him from Rembrandt and Soutine. If there is an "interpretation" of the body in Bacon, it lies in his taste for painting prone Figures, whose raised arm or thigh is equivalent to a bone, so that the drowsy flesh seems to descend from it. Thus, we find the two sleeping twins flanked by animal-spirit attendants in the central panel of the 1968 triptych; but also the series of the sleeping man with raised arms, the sleeping woman with vertical legs, and the sleeper or addict with the hypodermic syringe. Well beyond the apparent sadism, the bones are like a trapeze apparatus (the carcass) upon which the flesh is the acrobat. The athleticism of the body is naturally prolonged in this acrobatics of the flesh. We can see here the importance of the fall [chute] in Bacon's work. Already in the crucifixions, what interests Bacon is the descent, and the inverted head that reveals the flesh. In the crucifixions of 1962 and 1965, we can see the flesh literally descending from the bones, framed by an armchair-cross and a bone-lined ring. For both Bacon and Kafka, the spinal column is nothing but a sword beneath the skin, slipped into the body of an innocent sleeper by an executioner. Sometimes a bone will even be added only as an afterthought in a random spurt of paint. Pity the meat! Meat is undoubtedly the chief object of Bacon's pity, his only object of pity, his Anglo-Irish pity. On this point he is like Soutine, with his immense pity for the Jew. Meat is not dead flesh; it retains all the sufferings and assumes all the colors of living flesh. It manifests such convulsive pain and vulnerability, but also such delightful invention, color, and acrobatics. Bacon does not say, "Pity the beasts," but rather that every man who suffers is a piece of meat. Meat is the common zone of man and the beast, their zone of indiscernibility; it is a "fact," a state where the painter identifies with the objects of his horror and his compassion. The painter is certainly a butcher, but he goes to the butcher's shop as if it were a church, with the meat as the crucified victim (the Painting of 1946 [3]). Bacon is a religious painter only in butcher's shops. I've always been very moved by pictures about slaughterhouses and meat, and to me they belong very much to the whole thing of the Crucifixion .... Of course, we are meat, we are potential carcasses. If I go into a butcher shop I always think it's surprising that I wasn't there instead of the animal. Near the end of the eighteenth century, the novelist K. P. Moritz described a person with "strange feelings": an extreme sense of isolation, an insignificance almost equal to nothingness; the horror of sacrifice he feels when he witnesses the execution of four men, "exterminated and torn to pieces," and when he sees the remains of these men "thrown on the wheel" or over the balustrade; his certainty that in some strange way this event concerns all of us, that this discarded meat is we ourselves, and that the spectator is already in the spectacle, a "mass of ambulating flesh"; hence his living idea that even animals are part of humanity, that we are all criminals, we are all cattle; and then, his fascination with the wounded animal, a calf, the head, the eyes, the snout, the nostrils ... and sometimes he lost himself in such sustained contemplation of the beast that he really believed he experienced, for an instant, the type of existence of such a being ... in short, the question if he, among men, was a dog or another animal had already occupied his thoughts since childhood. Moritz's passages are magnificent. This is not an arrangement of man and beast, nor a resemblance; it is a deep identity, a zone of indiscernibility more profound than any sentimental identification: the man who suffers is a beast, the beast that suffers is a man. This is the reality of becoming. What revolutionary person - in art, politics, religion, or elsewhere - has not felt that extreme moment when he or she was nothing but a beast, and became responsible not for the calves that died, but before the calves that died? But can one say the same thing, exactly the same thing, about meat and the head, namely, that they are the zone of objective indecision between man and animal? Can one say objectively that the head is meat (just as meat is spirit)? Of all the parts of the body, is not the head the part that is closest to the bone? Look again at El Greco or Soutine. Yet Bacon does not seem to think of the head in this manner. The bone belongs to the face, not to the head. According to Bacon, there is no death's-head. The head is deboned rather than bony, yet it is not at all soft, but firm. The head is of the flesh, and the mask itself is not a death mask, it is a block of firm flesh that has been separated from the bone: hence the studies for a portrait of William Blake [20, 21]. Bacon's own head is a piece of flesh haunted by a very beautiful gaze emanating from eyes without sockets. And he pays tribute to Rembrandt for having known how to paint a final self-portrait as one such block of flesh without eye sockets.6 Throughout Bacon's work, the relationship between the head and meat runs through a scale of intensity that renders it increasingly intimate. First, the meat (flesh on one side, bone on the other) is positioned on the edge of the ring or the balustrade where the Figure-head is seated [3]; but it is also the dense, fleshly rain that surrounds the head and dismantles its face beneath the umbrella [65]. The scream that comes out of the Pope's mouth and the pity that comes out of his eyes have meat as their object [27]. Later, the meat is given a head, through which it takes flight and descends from the cross, as in the two preceding crucifixions . Later still, Bacon's series of heads will assert their identity with meat, among the most beautiful of which are those painted in the colors of meat, red and blue [26]. Finally, the meat is itself the head, the head becomes the nonlocalized power of the meat, as in the 1950 Fragment of a Crucifixion , where the meat howls under the gaze of a dog-spirit perched on top of the cross. Bacon dislikes this painting because of the simplicity of its rather obvious method: it had been enough to hollow out a mouth from solid meat. Still, it is important to understand the affinity of the mouth, and the interior of the mouth, with meat, and to reach the point where the open mouth becomes nothing more than the section of a severed artery, or even a jacket sleeve that is equivalent to an artery, as in the bloodied pillow in the Sweeney Agonistes triptych. The mouth then acquires this power of nonlocalization that turns all meat into a head without a face. It is no longer a particular organ, but the hole through which the entire body escapes, and from which the flesh descends (here the method of free, involuntary marks will be necessary). This is what Bacon calls the Scream, in the immense pity that the meat evokes. excerpt from the book: Francis Bacon: the logic of sensation by GILLES DELEUZE

0 Comments