|

by Steven Craig Hickman Phenomenology, then, is an essential cognitive task of confronting the threat that things pose in their very being. … After phenomenology, we can only conclude that a great deal of philosophizing is not an abstract description or dispassionate accounting, but only an intellectual defense against the threatening intimacy of things. – Timothy Morton, Realist Magic Peter Schwenger in his book The Tears of Things comes very close to the same central insight upon which Graham Harman has built his entire metaphysical edifice. We discover that for the most part the everyday tools that we use: hammers, rakes, pens, computers, etc., remain inconspicuous; overlooked by those of us who use such tools; noticing them, if at all, as necessities that help us get on with our own work. Yet, the paradox of this situation is that there are moments when the tool threatens us, becomes an obstacle to our enterprising projects, and it is at such moments that we suddenly awaken from our metaphysical sleep and notice these objects in a strange new light: when the hammer iron head flies free of the wooden handle, or the computer suddenly freezes, the screen goes black, then sparking and sending out small frissions of stench and smoke from the flat box that encases it; at such moments we become defensive, threatened by the power of these material objects that we no longer control, that in fact are broken and exposed, beyond our ability to know just what they are. We also become aware that the tool is part of a larger sphere: it does not exist in and of itself, but is applied to materials in concert with other tools to make something that may then be seen in its turn as “equipment for residency” in parallel to Le Corbusier’s famous pronouncement that “a house is a machine for living in.” The full network of equipment’s interrelated assignments and intentions makes up what the subject perceives as “world.” The dynamic of this world, at whatever level, is one of care – care of the subject’s being. The business of equipment, then, is not just to build an actual house but as much as possible, and in the broadest sense, to make the subject feel at home in the state of existing.1 Against this Heiddegerian world of comfort and care much of what we call modernist art incorporated the tools into their artistic charade in order to break our at homeness, to make us feel a more difficult strangeness and estrangement, to become Aliens in an Alien Land ( I play off Heinlein’s Stranger in a Strange Land). Against the order of meaning and description OOO prides itself in making things strange again, allowing the Master Signifiers that once ruled the world to fall away into darkness, withdrawn and empty of significance, uncanny and paradoxical guests to a banquet of the Real that can no longer be controlled by humans or scientific discourse. Listen to a master of philosophical mythography, Graham Harman, as he turns a Ferris Wheel into a lesson on Objects and the levels of being, occasional causality, and the inhuman withdrawnness of substance: The reader should pause and fix this image firmly in mind: a giant rotating wheel, carrying thousands of beings in a long arc ascending to the clouds and vanishing into the darkness of the earth. Let it spin dozens of times in your mind before we move on from this beautiful spectacle. Imagine the faint machinic whirr of its concealed engine, the creaking of its bolts, and the varied sounds emitted by the objects riding in its cars: from neighing horses to mournful woodwind ensembles. Imagine too the ominous mood in the vicinity as its cars plunge deep into the earth. Picture the wheel loaded with animals, bombs, and religious icons. Picture it creaking under the weight of its cargo and emitting a ghostly light as it spins along its colossal circuit. Imagine the artists and engineers of genius who designed such a thing. And consider the human culture that would arise nearby, with the wheel as its sacred point of reference.2 Timothy Morton in his new work reminds us that “the phenomenological approach requires a cycling, iterative style that examines things again and again, now with a little more detail here, then with a little more force there”.2 Harman does just that in his myth of the Wheel turning from light to dark to light again, a fabricated circle of machinic life that harbors the strangeness of existence itself, entities that cannot be charmed into eloquence accept as paradoxical creatures that inhabit the interstices of thought like fragments of a cyclic world. The great wheel rising and falling from the sky into the underbelly below the ground, the dramatic interplay of object and network, the countless entities circling into and out of our lives, some of them threatening and others ludicrous. The objects in the cars and those on the ground or in the chambers affect one another, coupling and uncoupling from countless relations— seducing, ignoring, ruining, or liberating each other. (Harman KL 69-72) As Morton remarks “thinking objects is one of the most difficult yet necessary things thinking can do—trying to come close to them is the point, rather than retreating to the grounds of the grounds of the possibility of the possibility of asserting anything at all”. Are as Harman would have it objects affect us and in fact these objects turning on the Wheel of Relations – as he terms it, “generate new realities” (Harman, KL 76). At the end of this little myth of wheels within wheels, the churning ocean of being and becoming, Harman remarks that “no point in reality is merely a solid thing, and none is an ultimate concrete event unable to act as a component in further events. In this respect, the cosmos might be described as a vast series of interlocking ferris wheels” (Harman, KL 175-177). This opening move leads me back to Timothy Morton and his new work where he tells us that to think this way about Objects all the way and all the way down as a series of interlocking machines is to begin to work out an object-oriented view of causality. “If things are intrinsically withdrawn, irreducible to their perception or relations or uses, they can only affect each other in a strange region out in front of them, a region of traces and footprints: the aesthetic dimension“. As he states it so eloquently in his introduction “Every aesthetic trace, every footprint of an object, sparkles with absence. Sensual things are elegies to the disappearance of objects.” I am reminded of his work within literary criticism of which he is a master. In his excellent essay The Dark Ecology of Elegy in the Oxford Handook to Elegy he remarks: Perhaps the future of ecological poetry is that it will cease to play with the idea of nature. Since ecology is, philosophically thinking how all beings are interconnected, in as deep a way as possible, the idea of nature, something ‘over there,’ the ultimate lost object … will not cut it. We will lose nature, but gain ecology. Ecological poetry must thus transcend the elegiac mode” (255). 4 And, yet, under the sign of the inhuman he brings us closer to the Sadean truth of the world. “What if ‘man’ was already a kind of ‘living sepulcher,’ an empty tomb, a ‘mere husk’ like the seeds of the rustling reeds? If is finally our intimacy with that which is the deepest and the darkest. Under these circumstances, elegy would perform the melancholy knowingness that we are machines” (269). It is in the darkness that ecology withdrawn within the inhuman begins to harbor that ecological thought of which Morton is the eloquent elegist: Dark ecology chooses not to digest the phobic-disgusting object. Instead it decides to remain with it in all its meaningless inconsistency (Zizek 1992:35-9). Dark ecology is the ultimate reverse of deep ecology. The most ethical act is to love the other precisely in their artificiality, rather than seeking their naturalness and authenticity. Dark ecology refuses to digest plants and animals and humans into ideal forms. Cheering your self up too fast will only make things more depressing. ‘Linger long’ (Alastor: 1. 98) in the darkness of a dying world. (269) As he reminds us in his new book “Doesn’t this tell us something about the aesthetic dimension, why philosophers have often found it to be a realm of evil? The aesthetic dimension is a place of illusions, yet they are real illusions. If you knew for sure that they were just illusions, then there would be no problem.” This is the realm of vicarious causation the place where the “aesthetic dimension floats in front of objects, like a group of disturbing clowns in an Expressionist painting or a piece of performance art whose boundaries are nowhere to be seen”. This aesthetic dimension was revived with Harman’s return to Aristotelian substantialist form, which forced him to revive the older occasional causation theories he termed vicarious causation because, as he remarks, it “requires no theology to support it. Any philosophy that makes an absolute distinction between substances and relations will inevitably become a theory of vicarious causation, since there will be no way for the substances to interact directly with one another” (Guerrilla Metaphysics: Phenomenology and the Carpentry of Things (Kindle Locations 83-85). As Morton in his new work remarks on this: I argue that causality is wholly an aesthetic phenomenon. Aesthetic events are not limited to interactions between humans or between humans and painted canvases or between humans and sentences in dramas. They happen when a saw bites into a fresh piece of plywood. They happen when a worm oozes out of some wet soil. They happen when a massive object emits gravity waves. When you make or study art you are not exploring some kind of candy on the surface of a machine. You are making or studying causality. The aesthetic dimension is the causal dimension. It still astonishes me to write this, and I wonder whether having read this book you will cease to be astonished or not. Even though I come out of the traditions of Spinoza, Schopenhauer, Schelling, Hegel, Nietzsche, Bataille, Deleuze, Zizek and Land, and am definitely in the opposing insubstantialist stance within the philosophical spectrum, I still admire the power of this older formalism of substance. I have yet to finish this work by Timothy but have enjoyed the stimulation of its alternative traditions descending as they do from those Great Originals, Plato and Aristotle. And, even if I fit within their competitors loquacious if insubstantial or immanent tradition – that tributary river of another materialism (Epicurus and his epigones, who down the ages has spawned varying proposals concerning matter and the void) I still affirm those who hold to the flame of materialism no matter which path they follow. Read online: Realist Magic: Objects, Ontology, Causality 1. Peter Schwenger. The Tears of Things. (University of Minnesota, 2006) 2. Harman, Graham (2010-11-26). Circus Philosophicus (Kindle Locations 27-34). NBN_Mobi_Kindle. Kindle Edition. 3. Timothy Morton. Realist Magic: Objects, Ontology, Causality (Open Humanities Press An imprint of MPublishing, University of Michigan Library, ©2013) 4. The Oxford Handbook of The Elegy. Edited by Karen Weisman (Oxford University Press, 2010) The article is taken from:

0 Comments

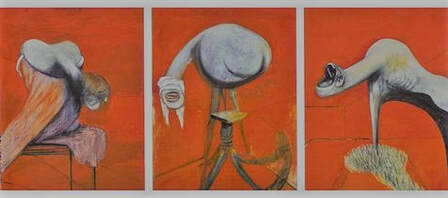

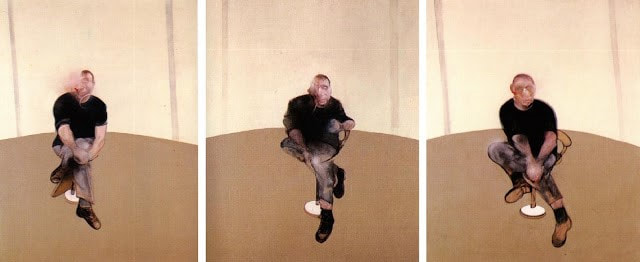

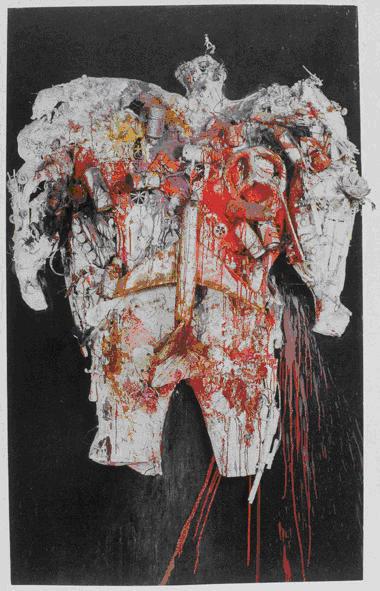

by Steven Craig Hickman The point is that the relation, the subjective relation between an event and the world cannot be a direct relation. -Alain Badiou: The Subject of Art "Meraki" Acrylic on canvas, 50x40 cm BTW One often wonders what truly is going on in Badiou’s mind as he prepares for his lectures. Reading the lecture I quoted above in the link I sit back in wonderment at the childlike simplicity of his statements, as if the audience before him were all ten year old kids and he the master was trying his best to lead them through the intricate yet simple realms of Alice’s Wonderland. His voice is charming and eloquent, decisive and pure, yet one is tempted to smile and realize that the Master has gone over this track too many times, that it is all too confident, too precise and mathematical for our taste. It’s as if he is trying to convince not the audience but himself of the simplicity of his system, to make sure that each and every aspect of its labored precision still fits the measure of his tempered mind. And, does it? Is this trifold world of being qua being, being-in-the-word, and the event truly locked down in such a methodical fashion as to allow for no critical injunctions? Badiou like Zizek always begins and ends with the Subject as that point in the world where something new happens: The point is that the relation, the subjective relation between an event and the world cannot be a direct relation. Why? Because an event disappears on one side, and on the other side we never have a relation with the totality of the world. So when I say that the subject is a relation between an event and the world we have to understand that as an indirect relation between something of the event and something of the world. The relation, finally, is between a trace and the body. I call trace ‘what subsists in the world when the event disappears.’ It’s something of the event, but not the event as such; it is the trace, a mark, a symptom. And on the other side, the support of the subject—the reality of the subject in the world—I call ‘a new body.’ So we can say that the subject is always a new relation between a trace and a body. It is the construction in a world, of a new body, and jurisdiction—the commitment of a trace; and the process of the relationship between the trace and the body is, properly, the new subject. (here) When I saw that word ‘trace’ rise up in the above sentences I was reminded of another French philosopher, Jaques Derrida, for whom trace became a catch word. In the 1960s, Derrida used this word in two of his early books, namely “Writing and Difference” and “Of Grammatology”. Because the meaning of a sign is generated from the difference it has from other signs, especially the other half of its binary pairs, the sign itself contains a trace of what it does not mean. One cannot bring up the concepts of woman, normality, or speech without simultaneously evoking the concepts of man, abnormality, or writing. The trace is the nonmeaning that is inevitably brought to mind along with the meaning.” Is there a connection? I doubt it, only the connection in my own mind between two distinctly independent and intelligent philosophers that obviously with careful reading probably questioned each other to no end, yet read each other deeply and contentiously. Their thought converges and diverges on the concept of the event. I’d have to spend too much time to tease out the complexity of both philosophers conceptions to do that in a blog post so will end here. Read the above essay if you will for it lays down in a few words the basic architectural units of Badiou’s whole system of philosophy. One could do no better than read it and either follow it up with a deep reading of his major works Being and Event and The Logic of Worlds, or toss it into the trash and follow one’s own inclinations toward other climes. I leave that to the reader to choose. For me it is enough to realize that Badiou is someone you cannot pass over, but must confront with all the rigor that he brings to his own project. That there can be no direct relation between the event and the world to me seems to fit nicely into many of the strands of current philosophical speculation. This is a philosophy of movement, of happening, not of closure and stasis. The idea of indirect relation is processual in its dynamics, yet is also gathered into the net of mathematical precision as the intersection of relations defined as the movement between world and body, subject and its field of newness. Where does this take us? I’ll only leave you with one last tidbit from the lecture: So the subject of art is not only the creation of a new process in its proper field, but it’s also a question of war and peace, because if we don’t find the new paradigm—the new subjective paradigm—the war will be endless. And if we want peace—real peace—we have to find the possibility that subjectivity is really in infinite creation, infinite development, and not in the terrible choice between one form of the power of death (experimentation of the limits of pleasure) and another form of the power of death (which is sacrifice for an idea, for an abstract idea). That is I think, the contemporary responsibility of artistic creation. Taken from: by Steven Craig Hickman “Bacon’s bodies, heads, Figures are made of flesh, and what fascinates him are the invisible forces that model flesh or shake it. This is the relationship not of form and matter, but of materials and forces making these forces visible through their effects on the flesh.” – Gilles Deleuze, Francis Bacon: the logic of sensation The ripple of flesh, the slippery lushness just below the surface plane, the immanent materials and forces, the “violence of a sensation (and not of a representation), a static or potential violence, a violence of reaction and expression” (x), these are demarcations of a philosophy of life rather than death. Against the old religions, the monotheistic tribalism of the sky: the dark powers of hierarchy, of the One who beholds, who sees all, whose gaze orders everything into a system of justice and retribution: under the law that keeps everything bound to its harsh justice and stringent banishments; instead of this dead and deadening judgment that hands down decrees and punishments, enforces the legal inducements of final Heavens of the Immortals or Eternal Judgments in Lakes of Fire (for all who do not follow the dictates of this fierce power). Against this harsh world Deleuze offers us the immanent law of rebellion, of force, of flows that churn within like so many coagulating sperm infested snakes that want to escape: the spasmodic, the serpentine liquidity, the “revelation of the body beneath the organism, which makes organisms and their elements crack or swell, imposes a spasm on them, and puts them into relation with forces sometimes with an inner force that arouses them, sometimes with external forces that traverse them, sometimes with the eternal force of an unchanging time. sometimes with the variable forces of a flowing time” (160). Three Studies for Figures at the Base of a Crucifixion, 1944. Oil and pastel on Sundeala board. Tate Britain, London Egyptian painted figures float in an abstract space that is neither here nor there. The background is coolly blank. Everything is flattened into the foreground, an eternal present where serenely smiling pharaohs offer incense and spools of flax to the gods or drive their chariot wheels over fallen foes. Women strike tambourines, dance as the forces of the earth rise in their young lithe bodies. Hieroglyphics hang in midair, clusters of sharp pictograms of a rope, reed, bun, viper, owl, human leg, or mystic eye. “Can the Egyptian assemblage be taken as the point of departure for Western painting? It is an assemblage of bas-relief even more than of painting,” says Deleuze (122). The Bas-relief is the flat plane of the ontic, the place where eye and hand meet on the surface, the terraform that cleaves the haptic, the layers of movement no longer above or below but moving along the surface unhindered by the chains of chance or necessity. “It is thus a geometry of the plane, of the line, and of essence that inspires Egyptian bas-relief; but it will also incorporate volume by covering the funerary cube with a pyramid;that is, by erecting a Figure that only reveals to us the unitary surface of isosceles triangles on clearly limited sides. It is not only man and the world that in this way receive their planar or linear essence; it is also the animal and the vegetal, the sphinx and the lotus, which arc raised to their perfect geometrical form, whose very mystery is the mystery of essence” (123). In line with Lucretius, needing to make visible the forces below the threshold of things, Deleuze touches the heart of art in deformation, the elastic or plastic deformations that are productive of temporal fluctuations harboring the monstrous truth of being: “they are like the forces of the cosmos confronting an intergalactic traveler immobile in his capsule” (58). The transformation of form can be abstract or dynamic. But deformation is always bodily, and it is static, it happens at one place; it subordinates movement to force, but it also subordinates the abstract to the Figure (59). The deformation is obtained in the form at rest; and at the same time, the whole material environment, the structure, begins to stir: “walls twitch and slide, chairs bend or rear up a little, cloths curl like burning paper…. “(60). The aesthetics of forces inhabiting the geometry of flows and fluctuations that move discordantly up through the tongue in the moment of becoming visible, the “visibility of the scream (the open mouth as a shadowy abyss) and invisible forces, which are nothing other than the forces of the future” (61): “When, like a wrestler, the visible body confronts the powers of the invisible, it gives them no other visibility than its own. It is within this visibility that the body actively struggles, affirming the possibility of triumphing, which was beyond its reach as long as these powers remained invisible, hidden in a spectacle that sapped our strength and diverted us. It is as if combat had now become possible. The struggle with the shadow is the only real struggle” (62). This is the agon with duende – the force of the sublunar, the chills that spring forward out of the shadows in our moments between, makes one smile or cry as a bodily reaction to an artistic performance that is particularly expressive. Folk music in general, especially flamenco, tends to embody an authenticity that comes from a people whose culture is enriched by diaspora and hardship; vox populi, the human condition of joys and sorrows. Lorca writes: “The duende, then, is a power, not a work. It is a struggle, not a thought. I have heard an old maestro of the guitar say, ‘The duende is not in the throat; the duende climbs up inside you, from the soles of the feet.’ Meaning this: it is not a question of ability, but of true, living style, of blood, of the most ancient culture, of spontaneous creation.” He suggests, “everything that has black sounds in it, has duende. … This ‘mysterious power which everyone senses and no philosopher explains’ is, in sum, the spirit of the earth, the same duende that scorched the heart of Nietzsche, who searched in vain for its external forms on the Rialto Bridge and in the music of Bizet, without knowing that the duende he was pursuing had leaped straight from the Greek mysteries to the dancers of Cadiz or the beheaded, Dionysian scream of Silverio’s siguiriya.” … “The duende’s arrival always means a radical change in forms. It brings to old planes unknown feelings of freshness, with the quality of something newly created, like a miracle, and it produces an almost religious enthusiasm.” …”All arts are capable of duende, but where it finds greatest range, naturally, is in music, dance, and spoken poetry, for these arts require a living body to interpret them, being forms that are born, die, and open their contours against an exact present” (Theory and Play of the Duende). Head VI, 1949. 93.2 × 76.5 cm (36.7 × 30.1 in), Arts Council collection, Hayward Gallery, London Or as Deleuze eloquently states it “Life screams at death, but death is no longer this all-too visible thing that makes us faint; it is this invisible force that life detects, flushes out, and makes visible through the scream. Death is judged from the point of view of life, and not the reverse, as we like to believe” (62). … There is the force of ‘banging time, through the allotropic variation of bodies, down to the tenth of a second,” which involves ”’formation; and then there is the force of eternal time, the eternity of time, through the uniting separating that reigns in the triptychs, a pure light. To render time sensible in itself is a task common to the painter, the musician, and sometimes the writer. It is a task beyond all measure or cadence” (64). The famously filthy mess that was Bacon’s studio at Reece Mews – the piles and sticky avalanches of photos, books, clipped newsprint, booze-stained scribbles on the verge of becoming drawings, squished paint tubes and every imaginable ingredient of clutter that covered the horizontal and vertical surfaces, tables and walls, like some illegible compost in which, like molds or somewhat alien life-forms, his future pictures were brewing and his past ones decaying. This stuff was more than rubbish. It was an archive, admittedly a staggeringly disordered one. An archive of the deformations that arise out of the earth itself to grasp hold of our very thoughts, and scream… the painters visions of that moment of deformation that implodes and gives birth at the same time. Out of disorder order shapes us, moves through us, spasmodically, and with desperate disjunctive sounds of the duende… “It is not I who attempts to escape from my body, it is the body that attempts to escape from itself by means of…. in short, a spasm: the body as plexus, and its effort or waiting for a spasm” (15). “Time is no longer the chromatism of bodies; it has become a monochromatic eternity. An immense space-time unites all things, but only by introducing between them the distance of a Sahara, the centuries of an aeon: the triptych and its separated panels… There are nothing but triptychs in bacon: even the isolated paintings are, more or less visibly, composed like triptychs” (85). An inversion of the ancient Christian formalism, Bacon’s triptychs remind us not so much of icons of some transcendent deity, but rather as the immanent movement of those strange forces that surface and withdraw, channel their rapprochement or negotiate between the triple aspects of being that is always and forever the faces of Time past, present, and future: the motion of a pendulum that carves and deforms us even as death awakens within us the flowers of life itself. “Like Lucretius’s simulacrum, …seem to him to cut across ages and temperaments, to come from afar, in order to fill every room or every brain” (91). These triple non-forms are the strokes of a cosmic catastrophe: “It is like the emergence of another world. For these marks, these traits, are irrational, involuntary, accidental, free, random. They are nonrepresentative, nonillustrative, nonnarrative. They are no longer either significant or signifiers: they are asignifying traits” (101). The monstrous void opens inward revealing nothing less than the face of an abyss that cannot be described nor represented for it is the face of the inhuman other that for so long has been banished, exiled among its own dark thoughts, riven of its place within the fold, the flows of time’s dark prison. But the path to salvation is not easy. No. But are atheists allowed salvation? Is art a form of salvation? Are the paths of artistic expression forms of freedom? And, what of these paths? “Abstraction would be one of these paths, but it is a path that reduces the abyss or chaos (as well as the manual) to a minimum: it offers us an asceticism, a spiritual salvation. Through an intense spiritual effort, it raises itself above the figurative givens, but it also turns chaos into a simple stream we must cross in order to discover the abstract and signifying Forms” (103). The Second Path leads another way: “A second path, often named abstract expressionism or art informed oilers an entirely different response, at the opposite extreme of abstraction. This time the abyss or chaos is deployed to the maximum. Somewhat like a map that is as large as the country, the diagram merges with the totality of the painting; the entire painting is diagrammatic” … In the unity of the catastrophe and the diagram, man discovers rhythm as matter and material. (104 – 107). These diagrams offer recompense, only if we can differentiate between the triptych diagrams. But we can also date the diagram of a painter, because there is always a moment when the painter confronts it most directly. “The diagram is indeed a chaos, a catastrophe, but it is also a germ of order or rhythm. It is a violent chaos in relation to the figurative givens, but it is a germ of rhythm in relation to the new order of the painting” (102). As Bacon says, it “unlocks areas of sensation.” The diagram ends the preparatory work and begins the act of painting. There is no painter who has not had this experience of the chaos-germ, where he or she no longer sees anything and risks foundering: the collapse of visual coordinates. Ultimately this is a tale of facts, of the power of non-representational painting, the ardour of emergence and flow, the moment of facticity: “…the forms may be figurative, and there may still be narrative relations between the characters – but all these connections disappear in favor of a ‘matter of fact’ or a properly pictorial (or sculptural) ligature, which no longer tells a story and no longer represents anything but its own movement, and which makes these apparently arbitrary elements coagulate in a single continuous flow” (160). Gilles Deleuze. Francis Bacon: the logic of sensation. Continuum 2003 The article is taken from: by Aryan Kaganof It is worth reminding ourselves why many people think August Highland a great modern poet. The first thing to say is that without him it would have been impossible for the Metapoetics Theatre movement to cohere or become a public sensibility, a symptomatic art for the age. The details of his part in the Hyper-Literary Fiction movement, and the part he played in forming and feeding its views, have been accumulating over the years in which scholars and critics have looked back to San Diego in 1998-2003 as an optimum time of creation. The moment of the Genre Splice is superluminal. It arrives before it was sent. Hyper-Literary Fiction is never on time. It’s time is a perpetuum mobile of memories of what happens next. Next-Gen Nanopoetics is Zarathustra’s eternal recurrence, vibrating fast enough for your ears to see it and slow enough for your eyes to hear it. The prime characteristic of the Genre-Splicer is that he does not tell a story. The Genre-Splicer creates an emptiness of literature. But this emptiness was already there. It merely needed to be filled. With Genre-Splices the sources of contemporary literature are exposed in their emptiness. What is expelled from the screen page is hysteria, ie. contemporary literature itself. Hyper-Literary Fiction is never finished. Genre-Splices always beg the question: when may we begin again? Each of the Genre Splices August Highland makes is trying to say the whole thing, i.e. the same thing over and over again. It is as though they were all simply views of one object seen from different angles. The closest Microlinear Storytelling gets to Once Upon A Time is Always Now. The Hyper-Literary Fiction of value always invokes deja-vu. Genre-Splicing is addictive. In a way having one’s writings Genre-Spliced is like eating from the tree of knowledge. The knowledge acquired sets us new (ethical) problems; but contributes nothing to their solution. Sometimes a Genre-Splice can be understood only if it is experienced at the right tempo. August Highland’s Hyper-Literary Fiction is all supposed to be read very fast. Hyper-Literary Fiction gazes into abysses, which it should not veil from sight nor can conjure away. The key to Genre-Splicing lies undoubtedly hidden somewhere in our complex sexual nature. Hyper-Literary Fiction is ANNIHILATIVE! The Metapoetics Theatre movement probably reached its most distilled meaning in August Highland’s own career, where the notion of “the hard textimage” did acquire an authoritative centrality, but nonetheless it most certainly offered many essential constituents fundamental to modern Genre-Splicing lore – the free line, “superpositioning”, crack, etc. One thing that can be said in his favour is that August Highland always went in pursuit of a redemptive kinesis.  Aryan Kaganof is an award-winning avant-garde filmmaker, writer and artist living in Gauteng. He is one half of South African Noise duo Virgins. The article is taken from:

by Marcel Wesdorp

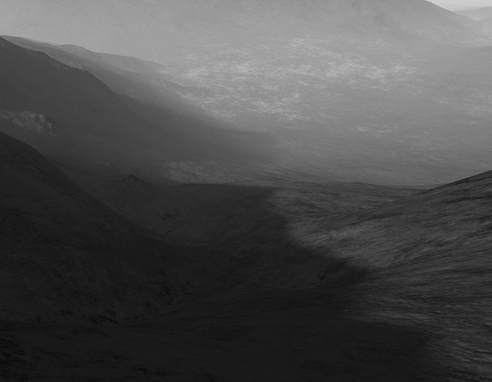

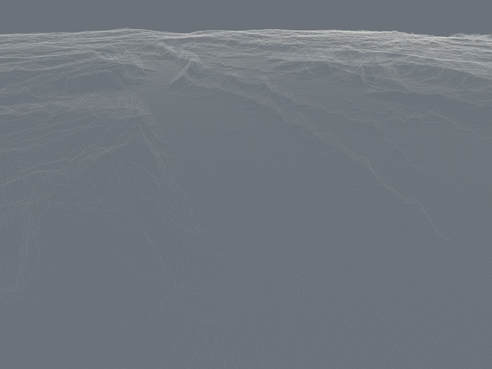

Prints of these digitally developed areas seem to be real photographs, uniquely named by their specific xyz co-ordinates. But at a second glance you are struck by an unknown reality that lies beyond. Some steps in this process lead to unsuspected and surprisingly catching images, each of them with a most sensitive and enigmatic touch, as may be seen in his PW series.

loading...

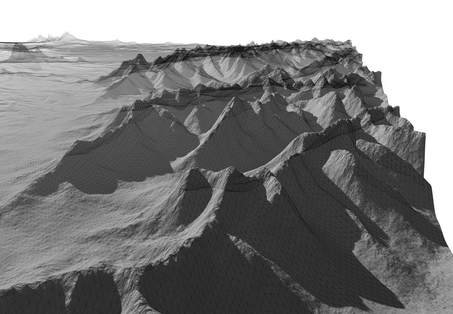

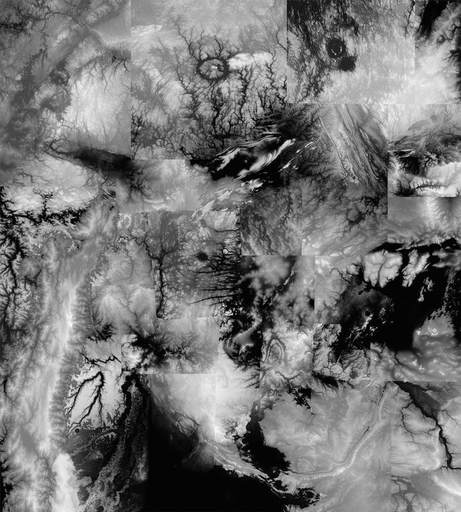

Apart from the purely software based techniques, the collection and modelling of existing satellite data and maps is a second intricate field of work of the artist. Here another elaborate few years were needed to complete the paper-printed black and white ‘Untitled World File’. Wesdorp’s fine imagination of scale and proportion makes you dazzle for this vacuum of time and space. The work originates from a real love history, only to be revealed to the viewer when taking time to see its dimensions.

x4207.44/y2809.41/z258.51 - 2011

x1288.20/y6028.21/z285.40 - 2010

x3435.26./y5201.54/z-9.14 - 2011

x7457.29/y9325.47/z226.42 - 2012

loading...

Out of NothingOut of nothing from Marcel Wesdorp on Vimeo.

2007/2010 - 02:05 hour [fragment]

x86946.1/y55460.1-3838.8 - 2015/16

x52059.4/y2598.8-2161 - 2015

Untitled World - 2015

Untitled World-File - 2014/2015

MINE 'compiled world file' 2017

Marcel Wesdorp

Born in Netherlands (1965) and graduated at Willem de Kooning Academy -Rotterdam and the advanced programme in photography at St. Joost Academy in Breda, Wesdorp creates computerized animations of landscapes.