|

by Aryan Kaganof

Veracruz, painted by Jesus Sepulveda

Art operates like a symbolic appropriation of reality. The act of representing reality or mediating our relation with the world—through an object or product of symbolic art—reinforces the process of reification. Art is a representation that replaces reality. in this same way it is a form of mediation of social and inter-subjective relations. said mediation is produced through cognitive reason, which filters the modes of appreciation of reality. becoming familiar with reality, the subject internalizes it. this is an appropriation that occurs, straining reality through a utilitarian and functional sieve. the codes of the filter are the codes of instrumental rationality, which projects the expansion of the subject’s interiority over the world’s exteriority. this develops the cognitive mechanisms of appropriation, categorization, and control of the other—that which is always unknown and unfamiliar. these mechanisms are the product of fear of the outside. because of this, the projection of interiority upon the exterior world produces an expansive and colonizing zeal. this zeal in turn projects the ego over the other: the external world (nature), and the creatures that inhabit it (human beings, animals, plants, and the soil). the expansive projection of the “i” over nature accelerates the process of reification.

kant was enraptured by the majestic spectacle of nature. this emotion produced in him a kind of “mental agitation,” which he called “sublime.” but this emotion is also the living experience of the dread that is sublimated through art, the petrification of the natural spectacle of the world. when art is an institution or a mere object— symbolic and separated from life—it is converted into a symbol of the process of reification. sophisticated meta-art is nothing more than a symbol of the symbol, a reification of reification. this process sharpens the ideological mechanism of the reification of the subject itself, which, when commodified, alienates itself from reality and loses perspective. to replace instrumental reason with aesthetic reason does not mean simply replacing the mechanisms of reification. reification in art exists because art symbolizes that which has been taken from life—the experience of beauty. art and life have been divided into two separate planes, without any real interconnection. this makes art an institution of the sublime, while life is the praxis of enslavement. art has been the pressure release valve of alienation. traditionally it has sheltered those values and energies distanced from life, permitting the maintenance throughout “history” of the illusion of humanity. the separation between art and reality has created a situation in which both planes of experience are lived as isolated spheres, without spirit or emotion. art becomes petrified in museums, in galleries, in salons and libraries, while existence continues to the rhythm of the minute hand that subjugates salaried work. there, beauty is suppressed, joy domesticated, pleasure enslaved, and peculiarity made uniform. art is the negative mirror of reality that compensates for the miseries of life with the illusion of liberty. to remove art from the sphere of the institution means living art in life and vice versa. it means destroying the alienation that implies the distinction between the artistic and intellectual, and the vulgar and manual. it means beautifying life and enlivening art, both as a unified and organic whole. it also means creating a humanity of artists, and humanizing the artists who already exist. VENUS IN FURS from African Noise Foundation on Vimeo.

taken from:

0 Comments

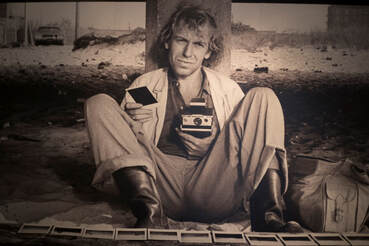

by David Roden Charles Sheeler, Catastrophe No. 2, 1944 Here, one of my favourite critical theorists/philosophers Claire Colebrook talks about the role of art in thinking and imagining the end of the world. The bottom line, for her, is that only a certain idea of art as decoupled from our immediate practices and functions, that which always relates to other worlds, allows us to think or angst about the end of ours. And by extension, only a world that appropriates or colonizes other worlds can have art as a value. “The logic of art” is also one of colonization. So post-apocalyptic dramas like Christopher Nolan’s Interstellar are both about the fragility of a certain kind of humanity (humanity defined in terms of its intelligence, its ability to “master” worlds) an an implicit demand that this humanity should be preserved: “The more exposed, fragile, vulnerable and damaged this future is imagined to be, the more forceful the heroic narrative of salvation.” The end of the world is the end of the human who does not merely exist “here and now.” but trades in objects and worlds and inscriptions that can be detached from their material origin while still being bound up with worlds. If there are no libraries, no geopolitics, no archives, no mathematics, there are no humans in this sense. Thus imagining a world without art is imagining the end of the world. “Only a world that has a sense of its specific end can demand that it not end” Tribes, cultures, languages, etc. can end, but the world that looks on these as worlds is “too big to fail”. This involves a concept of humanity so global that it implies the impossibility of its own outside precisely by imagining that outside. Colebrook’s piece prompted me to revisit a piece on Philosophical Catastrophism I wrote earlier this year, focused on catastrophe in Ballard, Brassier and Cronenberg. This also considered the catastrophe as unthinkable limit. However, there are some significant differences. The dust bowls of Mad Max and Interstellar are perfectly representable and thinkable. Indeed, as Colebrook reminds us, they resemble the fragile, hand to mouth existence of much of contemporary humanity more than the sheltered urban world typically threatened in popular end of the world scenarios. The “unthinkability” of the catastrophes considered in Colebrook’s talk is expressed as a normative or ethical demand (they are that which must never be). Those of Crash, Nihil Unbound, Videodrome, and the Hyperapocalypse are all literally unthinkable or, more precisely, unrepresentable. Ballard’s catastrophe is the ‘unique vehicle collision’ that would utterly transform our dreams and desires; thus transcending the novel’s patina of shattered machinery and ruptured, broken bodies. The thermonuclear war of the ‘Terminal Beach’ is the immense “historical and psychic zero” which generates sense by extirpating it. Its textual and ontological function is is to bind the decoupled moments of Ballard’s montage and of modernist time alike within its promiscuous absence. Whereas Colebrook’s apocalypses imagine worlds to subdue, Ballard’s event reproduces Being by promising to extirpate it. Brassier’s evocation of cosmic collapse in Nihil Unbound is likewise an attempt to decouple thought from Being, to think a reality that could never belong to or relate to a world. Brassier replicates Laruelle’s detachment of the Real from Being or intentionality but without reinstating it in the form of a gnosis of a bare humanity or inner life. Finally, Videodrome‘s viscid new flesh ramifies or plasticizes the barred subject of modernity beyond the point at which it or its erotic distance from the thing is sustainable. This “semantic apocalypse” is also a different kind of unworlding, if only because it forces us to redefine the globalizing human which forms the background to Colebrook’s reading of apocalyptic fiction. In a sense, this modernist subject is a myth that allows us to reclaim a modernity whose trajectory is fundamentally inhuman and asubjective. watch the video below: The article is taken from: by Andy McGlashen Wim Wenders is known primarily for his work as a film director, most notably Paris, Texas (1984) and Buena Vista Social Club (1999). He is also known for his photography and his images have been exhibited worldwide, more specifically his collection of Polaroids. Around 3,500 of his Polaroids survive (many had been given away immediately to the subjects in the photos), and the Photographers’ Gallery in London is currently exhibiting 200 of them in a collection titled “Instant Stories”. As well as the Polaroids (which are grouped into themes) there is an 8-minute documentary that Wenders made in 1978, which he has updated for the exhibition by adding narration. In the film he is an “actor” on a road trip with a prototype Polaroid SX-70 Land camera which was given to him by Polaroid to test. It is an interesting little film in its own right, and Wenders explains the attraction of Polaroid being the “missing link” (although I’m not sure to what extent it is missing) between film photography and the instant gratification of digital. He explains in his narration that Polaroids felt like a different act to photography and likened it to playing with a toy. This meant, he says, that taking pictures was playful and casual, and simply fun. Looking at the images in the gallery isn’t the easiest thing to do. They are of course standard Polaroids – around 3″ x 2.5″ – and mounted in frames, and my short-sightedness meant I was often squinting at the pictures from a distance of about two inches! The quality of the photos by today’s digitally airbrushed efforts (or even an amateur’s darkroom, I’m guessing) appears poor. They are often out of focus, or over- and under-exposed, or their colours are bleached, although a partial reason for this may be the passage of time and the quality of the original paper. I’m not sure anyone really expected the things to last 50 years or so. However, they often had a magnetic quality. Even though I was not drawn into all of the compositions, there was a palpable sense that you were viewing something through Wim Wenders’ eyes at the time. These images are not altered, distorted or enhanced from the little film that popped out from the front of the Polaroid camera all those years ago, and it felt like stepping into a time machine. Another aspect of the Polaroid is that it is undoubtedly the great-grandfather of the selfie. In today’s age of ubiquitous smartphones a selfie is something that is so instant we immediately see if something is a keeper (albeit we might not agree in future years if it’s committed to social media!) and throwaway others with a simple tap of the dustbin symbol. A Polaroid is also (almost) instant, but its cost meant that more often than not they were keepers and not consigned to a physical dustbin. I have never used a Polaroid and I can only guess at the sense of wonder and excitement as a picture crystallised before your very eyes. This is a great little exhibition and, although in hindsight probably more of a celebration of the Polaroid SX-70 than the images of Wim Wenders per se, it was fascinating to learn about both subjects. If I learnt anything about the creative aspects on show, it is to embrace a photo for what it is, play with randomness, and ensure that photography stays fun. taken from: |

ART

Archives

December 2017

art and aesthetics in art |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed