|

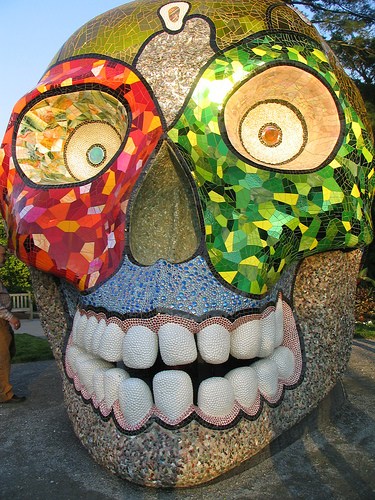

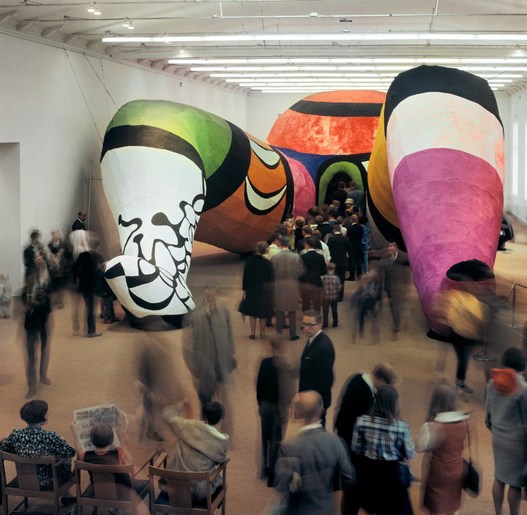

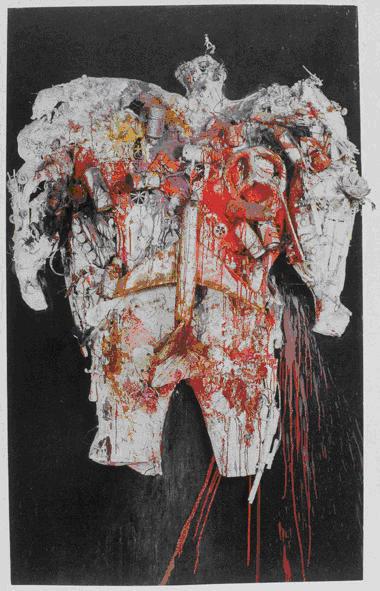

by Arran James Niki de Saint Phalle. “Le Cabeza”. Niki de Saint Phalle was a French sculptor, performance artist, painter, poster maker, writer, film-maker and feminist. A producer of voluptuous sculptures of female bodies that alternate between Goddess worship and the affirmation of vulnerability, her work is almost always oversized, brash and colourful. There is an innocence to her work that reflects her desire for her sculptures to be touched and literally inhabited. For instance, this skull was designed for human bodies to move around within it and to this day her intentions are being respected. She also wanted her art to communicate a sensuous call to children and after having taken our 5 year old to see an exhibition of her work at GoMA I can attest that it does. Even when her work is exploring the darkest of themes (and often her own lost innocence after being sexually assaulted as a child by her own father) her work’s instantiate a revealing in the production of an aesthetic sensibility of joyful abundance. Even threatening material remains an exotic flash of colour and warm with the softness of curves. Traditionally a leaden reminder of mortality and finitude, here the skull becomes playful, vivacious and obscene in size: death itself is captured as a thing of beauty and joy. The Great Devil. The Great Devil, like her “Nanas”, might be soft, voluptuous and inviting but they are also disfigured. Heads and arms appear under-developed or don’t appear at all and faces are obliterated. There is the suggestion of incompleteness within abundance and of an ambiguous reversibility of malevolent and nurturing forces. This might best be illustrated in her small but important book on Aids. In the materials she produced in her early “shooting paintings” de Saint Phalle also revealed the necessity of violence that subtends the creative process and would talk about the experience of watching the painting “bleed” colour. By taking aim at cans or balloons of paint she was able to force the canvas and the objects attached to it to reveal its corporeal dimension thereby revealing both it, and her own, vulnerability in a performative gesture. Her career as an artist was a therapeutic response to a “nervous breakdown” that centred on her traumatic exposure to male sexuality and so violence had both a demonic and cathartic operation in her art. What gesture could be more ambiguous than seizing the phallic power of the rifle and turning it on one’s own creations? Yet in making them bleed she punctures the paintings making them more than they were, rather than diminishing or killing them. a shooting painting In another of her enormous sculptures a giant Nana lays with her legs open while the spectators shuffle between her part labia and walk into her vagina. Adult bodies are returned to their infantile size by the effect of the relative scales of their organic and inorganic corporeal dimensions. Grown adults return to the womb having been made small and put in the mimetic place treacherous body of infancy and childhood. At one and the same time this is a return with both comforting and horrific aspects but which ultimately reminds each of us that our fragile bodies began as growths held within the uterus of our mothers. She: a cathedral We return to the place we have left as a collectivity and a public rather than as isolated children. At least in theory; galleries tend to be among the most alienating environments, which goes some way towards explaining why she often displayed her work in extra-institutional spaces. But it is not just as mother that this giant body welcomes us but as lover: the public enters the cunt of an artist who once described herself as one of ‘the biggest whores in the world’. There is no shame in this though- her body is big and welcoming and never closes, is never finished with new lovers. This is both the celebration of motherhood and of a particularly female eros. Furthermore, it is an eros that is indifferent to the sex, sexuality or gender identifications of those that enter her. And in entering we also see another aspect of the vulnerable corporeality of bodies: they penetrate (us) and our penetrable (sculpture); they may be broken into (sexual assault and rape) or they may welcome us (consensuality). This particular female body opens itself up to a waiting public and so loses performs or prophesies the time when female bodies aren’t considered in the negative as deprivation and confined to the private sphere. The very title, She: a cathedral, at once suggests congregations flocking to a Sacred space and the publicity that such spaces can take on. This is the happy side of feminism but de Saint Phalle is engages its more militant face too. La Mort du patriarche/Death of the patriarch In this shooting painting (or tir) we find that the patriarch is neither a male or female body but a blank white and sexless form. The body of the patriarch is not just a body but a territory bounded by darkness and populated by aircraft, missiles and torn apart dolls: the weapons of war and the broken bodies of their victims. The red explosion so obviously suggestive of blood emerges from the place where the heart is located in the popular imagination suggesting that the patriarch’s heart has exploded. Of course this is the effect created by the artist shooting it herself. If this is the dead body of the patriarch then the cause of death was assassination. At the same time as performing the destruction of the patriarch (at once patriarchy itself and the very “name-of-the-father” that had abused her and countless others) the painting is also an explicit and somehow lurid and stark elaboration on the relationship between that patriarchy, war and the image of femininity that women were expected to consume throughout the 1960s. In the time since it was first exhibited this angry feminist image has lost none of its power. In coming to the end of this appreciation- rather than review or critique- of Nikki’s de Saint Phalle’s work I wanted to turn to her own words. The exhibition at GoMA is accompanied by many quotations and features copies of her books. So it is odd that I can’t find any of her writing available online, except for non-preview e-books. The insurgent vitality of her artwork, often dismissed as merely “playful” and thereby missing the way that the early aggression still haunts the later work, sings and screams loudly about corporeality, sexuality, trauma, women and feminism; but her words seem to be largely ignored by the institutions and publications that announce her as cutting edge. This depoliticisation and repackaging as “exciting” “dangerous” or “innovative” is often the fate of political art within the circuitry of the art-market’s consumerism. So instead of reading some of what she had to say about the world and her own artistic practice, let’s watch her shooting the fuck out of a painting: The article is taken from:

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

ART

Archives

December 2017

art and aesthetics in art |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed