|

by JOSEPH NECHVATAL

Considering the Problem of Aesthetic Immersion: "Dioramas" at the Palais de Tokyo

Exhibition view of Jean Paul Favand, Naguère Daguerre III (2015) 19th century painted canvas, luminous installation and scenography, Musée des Arts Forains (Paris), courtesy of the artist. Photo Aurélien Mole

Dioramas

Palais de Tokyo 13 Avenue du Président Wilson, 16th arrondissement June 14 – September 10, 2017

Dioramas may or may not be your cup of tea, but they do clarify and confirm our latent immersive desire for intimate sublime space, something that has marginally existed in art and human culture throughout time. Anyone who has played with dolls or army men has a feel for the psychic projection of the diorama: a model representing a scene with three-dimensional figures in miniature. Subsequently, Palais de Tokyo’s current show Dioramas is impossible not to enjoy on that juvenile level. But the cultural feelings inherent in adult aesthetic immersion - which entails a lack of psychic spatial distance - need to be considered as well in this kind of show.

Armand Morin, Panorama 14 (2013-2017) Divers material, 260 x 260 x 300 cm Photo: Armand Morin. Courtesy of the artist

Charles Matton, L’Atelier de Giacometti (1987), photo by the author

Dioramas attempt to close the atmospheric gulf between the viewer and the aesthetic environment being viewed, something that is ideally dissolved in virtual reality’s 360-degree industrial standard of perfect functionality: total-immersion. Total-immersion, that state of virtual being which is considered the holy grail of the VR industry, can be characterized as a total lack of psychic distance between body-image and the immersive environment, accompanied by a feeling of plunging into another world. Dioramas are a cultural step towards total-immersion within the insinuated space of a virtual surrounding where everything within that sphere relates necessarily to the proposed "reality" of that world’s space and where the immersant is seemingly altogether disconnected from exterior physical space. As such, diorama’s immersion promotes a conflated but promiscuous ontological feeling of awareness where aesthetic cognition of the limits of the aesthetic environment attain the actual state of the generally subjective world of consciousness. Pushing back against that subjective seduction is the finest piece in the show: Richard Baquié’s 1991 remake facsimile of Marcel Duchamp’s Étant donnés: 1° la chute d'eau / 2° le gaz d'éclairage (1966); it deconstructs the illusionism behind all dioramas. One can circle the Étant donnés sculpture and see it for the first time from many angles, thus undercutting Duchamp’s original artistic peek-a-boo intentions.

Richard Baquié, Sans titre. Étant donnés: 1° la chute d'eau / 2° le gaz d'éclairage (1991), photo by the author.

Dioramas involve the viewer in a combination of the history of scenography, illusion, art, cinema, theatre, circus, science, and perception technology. Indeed, they are an apparent ancestor of immersive virtual reality. Their formal invention in the 19th century brought about an optical revolution and represented a turning point in the history of spectacle akin to the emergence of magic lanterns in the 17th century. Like virtual reality, dioramas seem to offer us the promise of an over-all make-believe world, or trips to the lost past. Two of the strongest works Diorama invoke the purpose of the diorama especially well: Charles Matton’s excellent L’Atelier de Giacometti (1987), and Armand Morin’s Panorama 14(2012). While Giacometti’s studio exudes meditative stillness, Panorama 14, a model of the amazing Canyon de Chelly animated by special effects and theatrical lighting, is rhythmed in time by a miniature sandstorm. This swooshing motion lends a feel of the sublime to the diorama, as shifting elements of ruddy scenery fade and emerge from the shifting landscape.

Armand Morin, Panorama 14 (2013-2017) Divers material, 260 x 260 x 300 cm Photo: Armand Morin. Courtesy of the artist

This sense of subtly shifting scenery evokes the diorama’s pre-history: the history of the panorama, a history that is given slight recognition here in this show. The name panorama is bestowed upon several forms of large-scale pictorial displays which enjoyed widespread popularity in the 18th and 19th centuries as applied to artificial installations that utilized a 360° view of a landscape or cityscape. These scenes were painted on the inside of a large cylinder and viewed from a platform at the cylinder’s center. This mode of optic display was officially invented and patented by Robert Barker, an Irish artist who lived and worked in Edinburgh. The original name for the panorama was the French term la nature à coup d'oeil, but in advertisements for its exhibition in London in 1791 Barker adapted the term panorama, which derives from the Greek words for all and view. This choice of words (all-view) indicates that what was strived for was an attempt at a total-view.

Mark Dion, Paris Streetcape (2017) Courtesy of the artist & Galerie In situ – Fabienne Leclerc (Paris). Photo: Aurélien Mole

Barker first exhibited his invention in 1787 in Edinburgh and in London in 1788. These presentations were considerably well-received by the public (the audience undoubtedly enjoyed being immediately surrounded on all sides by a three-dimensional interior) and their success enabled Barker to open a permanent rotunda for the exhibition of his panorama in London in 1793: the Leicester Square Panorama, which operated continuously for seventy years. However, prior to Barker’s achievement, several antecedents were put forth in Britain. In 1777, Thomas Hearne produced a sketch of Derwentwater that was 6.1 metres long (approximately 20 feet) for George Barret, who intended to have the scene painted on the walls of a circular banquet room. In 1781, Barret had painted the walls of a room at Norbury Park in Surrey with a continuous vista of the Cumberland Hills.

Jean-Paul Favand, Naguère Daguerre II (2012) View of the canvas illuminated from the back. 19th century painted canvas, luminous installation and scenography, 270 x 410 cm. Photo: Jean Mulatier. Courtesy Jean Paul Favand, Paris

Eschewing Barker et al, the show launches itself with the work of Louis-Jacques Daguerre, inventor of the daguerreotype, who, together with the architect/painter Charles-Marie Bouton, created the scenography diorama in 1822. This landmark work is here represented by Jean-Paul Favand’s 19th century painted canvases, luminously treated in a fluctuating fashion: Naguère Daguerre I and Naguère Daguerre II (both 2012). Like the panorama, the diorama was an attempt to recreate the appearance of 360-degree nature by means of painting and the mechanical regulation of light. Daguerre’s diorama consisted of a delicate cloth measuring about 14 by 22 metres (approximately 46 by 72 feet) painted with landscapes in a manner of the idyllic sublime. The audience sat in near-darkness as the picture was shown by means of daylight admitted through the windows, concealed both above the spectators and behind the painting by a system of shutters and colored filtering screens. These innovations were first shown at the Paris Diorama, which the two men constructed to seat 350 people at the Place de la République, which opened July 11th, 1822. On September 29th, 1823 the partners opened a second Diorama that seated 200, which could show two dioramas in succession by rotating the audience 73 degrees in London’s Regent’s Park. The Daguerre Diorama also made a tour of Britain and the east coast of America.

Jean-Paul Favand, Naguère Daguerre I (2012), View of the canvas illuminated from the front. 19th century painted canvas, luminous installation and scenography, 270 x 410 cm. Photo: Jean Mulatier. Courtesy Jean Paul Favand, Paris

Closely linked to the history of landscape painting and the emergence of the notion of the sublime, dioramas most often featured grandiose monuments and landscapes in the purest romantic tradition. These trompe-l’oeil compositions came to life thanks to ingenious lighting tricks, reflective mirrors, and colored glass - elements which together could create a range of atmospheric effects such as fog, sunlight, and dawn.

Following a dive into Daguerre’s original 1822 diorama, the Palais de Tokyo exhibition goes on to explore naturalist and ethnographic dioramas that consist of a glass case, a backdrop, and a selection of three-dimensional figures and objects. This exhibition trope is spoofed at the get-go: upon entering the Dioramas exhibit, one first is confronted by a short clip of the movie Night at the Museum, where Ben Stiller is trying to speak to Sacagawea in a glass box, but she can’t hear him. At once entertaining due to their spectacular character, pedagogical in their desire to tell a story, and highly plastic thanks to their painted backdrops and sculpted figures, ethnographic dioramas attest to the talent of the unknown artists, scientists, taxidermists, and architects who created them, therefore redefining the territory of art and its borders with technology.

Rowland Ward, Léopard et Guibs harnachés (1904) Diorama, 113 x 236 x 70 cm Photo: Alain Franchella / Région Auvergne-Rhône-Alpes. Courtesy of the Domaine royal de Randan (Randan)

Faced with the rise of Protestantism, the Catholic Church at the Council of Trent (1545-1563) found in the excesses of art a valuable ally with an undeniable power of attration. This clever development is illustrated with a collection of dioramas that show Biblical scenes or the lives of saints in three dimensions, such as Caterina De Julianis’s Santa Maria Maddalena in adorazione della croce (1717). Immersion into the image here proved to be a remarkably effective means of propagating the Catholic faith, and such models enjoyed a great deal of success from the 16th century onwards by stressing nativity scenes (that proliferated in churches come Christmas time) along with small-format, three-dimensional paintings that served as private devotional objects.

Caterina De Julianis, Santa Maria Maddalena in adorazione della croce (1717) Polychrome wax, painted paper, glass, tempera on paper and other materials, 53,7 x 59 cm. Photo: Artefotografica, Rome. Courtesy Galleria Carlo Virgilio & C, Rome

The show’s press release claims these Biblical scenes as the very first dioramas, with their three-dimensional elements set in a painted background. But this assertion is clearly wrong. Already in classical Greeco-Roman antiquity, there was a distinct contrast between the natural grotto (decorated with pumice stone, tufa, and shells and punctuated with sculpture and a diminutive pool of water) and the architectural grotto (where interior walls are coated in a mosaic of coloured pebbles, shells and coral in union with frescoes and sculpture). By the mid-16th century, almost every cognoscenti had a grotto of one of these types. The nymphaeum at Hadrian’s Villa (AD 134) at Tivoli is regarded as the most famous and influential grotto from Roman antiquity. In addition, the 1st-century BC Temple of the Sibylat Tivoli, which stands on a ledge of naturally caved rocks which were fitted-out as grottoes, served as a model for a good many of grottoes over time, including that at the Schloss Schwetzingen at Baden-Württemberg. The Blue Grotto at Capri served as a clear-cut model for the neo-rococo Venus Grotto (1877) at Linderhof. In the early half of the 18th century, when the impact of the Baroque could still be felt, an independent type of grotto architecture came into being in Germany whereby the grotto became associated with a garden green-room. The proliferation of seashells and glistening minerals, combined with painted frescos and stucco, is typical of this trend. Furthermore, already in the 16th century there evolved the autonomous pavilion grotto in France: a detached diminutive fabrication coated in tufa (e.g., Noisy-le-Roy (1599)); this form, less the tufa, became widely adapted in Germanic culture, including the Orpheus Grotto at Schloss Hellbrunn. In 1584, Bernardo Buontalenti installed a grotesque grotto at the Medici villa of Pratolina, which was famous for its water-driven mechanical automata.

Exhibition view of Walter Potter, Happy Family (ca 1870) Wood, glass, paint, paper, preserved animals. Private collection, courtesy of the artist. Photo: Aurélien Mole

Remarkably like the diorama, the mannerist Grotesque grotto is deliberately anti-realistic, often including elaborate depictions of multiple figures bound in tendrils. Mannerist Renaissance grottoes were placed in various locations: in the ground floor of buildings, as separate stand-alone structures, or tucked under terraces. Mannerist interior decorators esteemed the style inasmuch as it was suitably hoary in derivation, whimsical and playfully erotic, and capable, due to its all-over field approach, of fitting any required expanse. Many late-Renaissance grottoes were decorated in just such a grotesque and syncretistic fashion. Grotesque grottoes were created in a variety of extravagant shapes, but all were dedicated to the impulses of sex and love. Often the inside simulated an underwater cavern, replete with a mosaic coating of opened seashells suggestive of female genitalia. In that sense, grottoes represented the reverse side of Renaissance rationality by introducing into the ordered garden space of the formal garden a niche dedicated to the irrational realm of the mystic world in which rationalist rules need not apply. It is this aspect of the grotto which is the most relevant characteristic in formulating comparisons to the diorama's urge towards immersive space.

The interior grotto was greeted with a warm reception in France, starting as early as the regime of King François I (1494-1547). Its importance resides in the fact that the interior grotto inspired the immersive attributes of the Rococo Rocaille style, attributes that set the conditions for the diorama mania to follow. To sum-up: all interior grottoes shared with the diorama these following characteristics: the expansion of a precise formal visual idea, a taste for astonishment and special effects, the inflation of form, and an excessively self-confident premeditation.

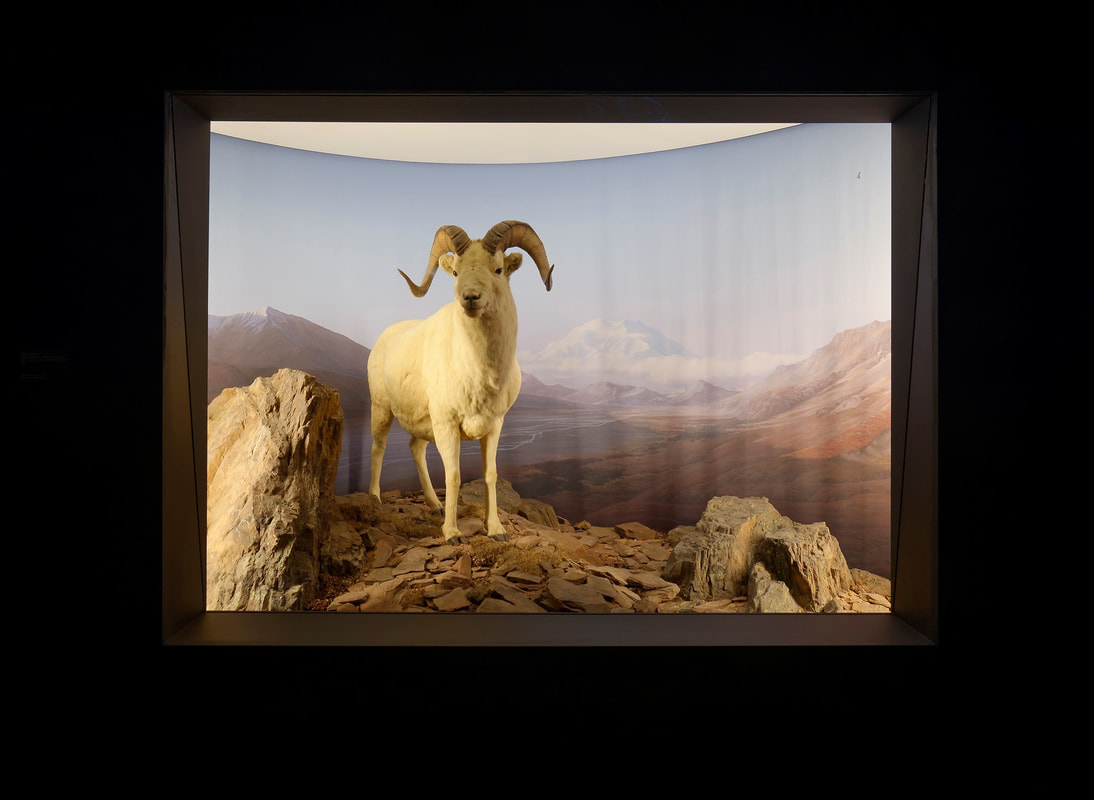

Exhibition view of Erich Böttcher, Mouflon de Dall, Denali National Park (1997) Mixed media, 400 x 190 x 238 cm. Bremen, Ubersee-Museum Bremen Courtesy of the artist. Photo: Aurélien Mole

To return to what is in the show, besides disliking the taxidermy in Rowland Ward’s Léopard et Guibs harnachés (1904) and Erich Böttcher’s Mouflon de Dall, Denali National Park(1997), what I definitely don’t like about dioramas - as opposed to grottoes - is how visually over-determined they are. How helplessly childish and passive they make us feel! It's similar to a point that Donna Haraway made in terms of bias in her essay Teddy Bear Patriarchy: Taxidermy in the Garden of Eden, New York City, 1908-1936. Their etymology would suggest that dioramas are about imaginarily "seeing through" a scene. But there is little transparency and/or simultaneity to be found in the diorama, which seems to be more about "seeing across" a space of objects into a deeper space, as with staged theatre. In understanding the frustration of the too-partial immersion of the diorama, we realize that the edification produced by their suggestions of artistic immersion is not merely the effect of social approval and disapproval, but of the taciturn, refining contact with our own private immersive desires. The private ideal of immersion that we harbor (that dioramas can only hint at) is an entry into the interrelational aorist space of binding that admits us into the realm of unknowingness and the non-self. As such, the reality of immersion is qualitatively and quantitatively distinct from what the diorama can offer. The esprit de corps of immersion is diaphanous hyper-being within a kind of experiential and excessive span where ocular extravagance is felt to be a function of the space. Its raison d'être is to supplant the framed deep gaze of the diorama by enticing vision into a more fully a posteriori understanding of vision’s potential in terms of peripheral attention. WM

JOSEPH NECHVATAL

Joseph Nechvatal is an artist whose computer-robotic assisted paintings and computer software animations are shown regularly in galleries and museums throughout the world. In 2011 his book Immersion Into Noise was published by the University of Michigan Library's Scholarly Publishing Office in conjunction with the Open Humanities Press. He exhibited in Noise, a show based on his book, as part of the Venice Biennale 55, and is artistic director of the Minóy Punctum Book/CD project. Follow Whitehot on Instagram view all articles from this author

The article is taken from:

in cooperation with JOSEPH NECHVATAL

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

ART

Archives

December 2017

art and aesthetics in art |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed