|

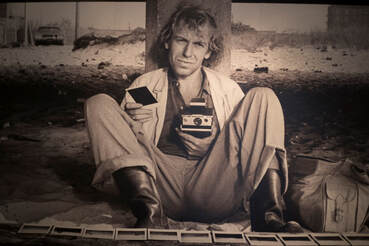

by Andy McGlashen Wim Wenders is known primarily for his work as a film director, most notably Paris, Texas (1984) and Buena Vista Social Club (1999). He is also known for his photography and his images have been exhibited worldwide, more specifically his collection of Polaroids. Around 3,500 of his Polaroids survive (many had been given away immediately to the subjects in the photos), and the Photographers’ Gallery in London is currently exhibiting 200 of them in a collection titled “Instant Stories”. As well as the Polaroids (which are grouped into themes) there is an 8-minute documentary that Wenders made in 1978, which he has updated for the exhibition by adding narration. In the film he is an “actor” on a road trip with a prototype Polaroid SX-70 Land camera which was given to him by Polaroid to test. It is an interesting little film in its own right, and Wenders explains the attraction of Polaroid being the “missing link” (although I’m not sure to what extent it is missing) between film photography and the instant gratification of digital. He explains in his narration that Polaroids felt like a different act to photography and likened it to playing with a toy. This meant, he says, that taking pictures was playful and casual, and simply fun. Looking at the images in the gallery isn’t the easiest thing to do. They are of course standard Polaroids – around 3″ x 2.5″ – and mounted in frames, and my short-sightedness meant I was often squinting at the pictures from a distance of about two inches! The quality of the photos by today’s digitally airbrushed efforts (or even an amateur’s darkroom, I’m guessing) appears poor. They are often out of focus, or over- and under-exposed, or their colours are bleached, although a partial reason for this may be the passage of time and the quality of the original paper. I’m not sure anyone really expected the things to last 50 years or so. However, they often had a magnetic quality. Even though I was not drawn into all of the compositions, there was a palpable sense that you were viewing something through Wim Wenders’ eyes at the time. These images are not altered, distorted or enhanced from the little film that popped out from the front of the Polaroid camera all those years ago, and it felt like stepping into a time machine. Another aspect of the Polaroid is that it is undoubtedly the great-grandfather of the selfie. In today’s age of ubiquitous smartphones a selfie is something that is so instant we immediately see if something is a keeper (albeit we might not agree in future years if it’s committed to social media!) and throwaway others with a simple tap of the dustbin symbol. A Polaroid is also (almost) instant, but its cost meant that more often than not they were keepers and not consigned to a physical dustbin. I have never used a Polaroid and I can only guess at the sense of wonder and excitement as a picture crystallised before your very eyes. This is a great little exhibition and, although in hindsight probably more of a celebration of the Polaroid SX-70 than the images of Wim Wenders per se, it was fascinating to learn about both subjects. If I learnt anything about the creative aspects on show, it is to embrace a photo for what it is, play with randomness, and ensure that photography stays fun. taken from:

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

ART

Archives

December 2017

art and aesthetics in art |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed