Hark! the voice of a pheasant

Has swallowed the wide field At a gulp.

Givochini, the famous comedian of the

Malii Theatre, was once forced to substitute at the last moment for the popular Moscow basso, Lavrov, in an opera, The Amorous Bayaderka. But Givochini had no singing voice. His friends shook their heads sympathetically. "How can you possibly sing the role, Vasili Ignatyevich?" Givochini was not disheartened. Said he, happily, "Whatever notes I can't take 'With my voice, I'll show with my hands."

Yamei

loading...

WE HAVE been visited by the Kabuki theater-a wonderful manifestation of theatrical culture.

Every critical voice gushes praise for its splendid craftsmanship. But there has been no appraisal of what constitutes its wonder. Its "museum" elements, though indispensable in estimating its value, cannot alone afford a satisfactory estimate of this phenomenon, of this wonder. A "wonder" must promote cultural progress, feeding and stimulating the intellectual questions of our day. The Kabuki is dismissed in platitudes: "How musical!" "What handling of objects!" "What plasticity! " And we come to the conclusion that there is nothing to be learned, that (as one of our most respected critics has announced) there's nothing new here: Meyerhold has already plundered everything of use from the Japanese theater!

Behind the fulsome generalities, there are some real attitudes revealed. Kabuki is conventional! How can such conventions move Europeans! Its craftsmanship is merely the cold perfection of form! And the plays they perform are feudal/-What a nightmare!

More than any other obstacle, it is this conventionalism that prevents our thorough use of all that may be borrowed from the Kabuki. But the conventionalism that we have learned "from books" proves in fact to be a conventionalism of extremely interesting relationships. The conventionalism of Kabuki is by no means the stylized and premeditated mannerism that we know in our own theater, artificially grafted on outside the technical requirements of the premise. In Kabuki this conventionalism is profoundly logical-as in any Oriental theater, for example, in the Chinese theater.

Among the characters of the Chinese theater is "the spirit of the oyster"! Look at the make-up of the performer of this role, with its series of concentric touching circles spreading from the right and left of his nose, graphically reproducing the halves of an oyster shell, and it becomes apparent that this is quite "justified." This is neither more nor less a convention than are the epaulettes of a general. From their narrowly utilitarian origin, once warding off blows of the battle-axe from the shoulder, to their being furnished with hierarchic little stars, the epaulettes are indistinguishable in principle from the blue frog inscribed on the forehead of the actor who is playing the frog's "spirit."

Another convention is taken directly from life. In the first scene of Chushingura (The Forty-Seven Ronin), Shocho, playing a married woman, appears without eyebrows and with blackened teeth. This conventionalism is no more unreal than the custom of Jewish women who shear their heads so that the ears remain exposed, nor of that among girls joining the Komsomol who wear red kerchiefs, as some sort of "form." In distinction from European practice, where marriage has been made a guard against the risks of freer attachments, in ancient Japan ( of the play's epoch) the married woman, once the need had passed, destroyed her attractiveness! She removed her eyebrows, and blackened (and sometimes extracted) her teeth.

Let us move on to the most important matter, to a conventionalism that is explained by the specific world-viewpoint of the Japanese. This appears with particular clarity during the direct perception of the performance, to a peculiar degree that no description has been able to convey to us.

And here we find something totally unexpected-a junction of the Kabuki theater with these extreme probings in the theater, where theater is transformed into cinema.· And where cinema takes that latest step in its development: the sound film. The sharpest distinction between Kabuki and our theater isif such an expression may be permitted-in a monism of ensemble. We are familiar with the emotional ensemble of the Moscow Art Theatre-the ensemble of a unified collective "re-experience" ; the parallelism of ensemble employed in opera (by orchestra, chorus, and soloists); when the settings also make their contribution to this parallelism, the theater is designated by that dirtied word "synthetic" ; the "animal" ensemble finally has its revenge-that outmoded form where the whole stage clucks and barks and moos a naturalistic imitation of the life that is led by the "assisting" human beings.

The Japanese have shown us another, extremely interesting form of ensemble-the monistic ensemble. Sound-movement-space-voice here do not accompany (nor even parallel) each other, but function as elements of equal significance.

The first association that occurs to one in experiencing Kabuki is soccer, the most collective, ensemble sport. Voice, clappers, mimic movement, the narrator's shouts, the folding screens-all are so many backs, half-backs, goal-keepers, forwards, passing to each other the dramatic ball and driving towards the goal of the dazed spectator.

It is impossible to speak of "accompaniments" in Kabuki-just as one would not say that, in walking or running, the right leg "accompanies" the left leg, or that both of them accompany the diaphragm!

Here a single monistic sensation of theatrical "provocation" takes place. The Japanese regards each theatrical element, not as an incommensurable unit among the various categories of affect (on the various sense-organs), but as a single unit of theater.

. . . the patter of Ostuzhev no more than the pink tights of the prima-donna, a roll on the kettledrums as much as Romeo's soliloquy, the cricket on the hearth no less than the cannon fired over the heads of the audience.

Thus I wrote in 1923, placing a sign of equality between the elements of every category, establishing theoretically the basic unity of theater, which I then called "attractions."

The Japanese in his, of course, instinctive practice, makes a fully one hundred per cent appeal with his theater, just as I then had in mind. Directing himself to the various organs of sensation, he builds his summation to a grand total provocation of the human brain, without taking any notice which of these several paths he is following.

In place of accompaniment, it is the naked method of transfer that flashes in the Kabuki theater. Transferring the basic affective aim from one material to another, from one category of "provocation" to another.

In experiencing Kabuki one involuntarily recalls an American novel about a man in whom are transposed the hearing and seeing nerves, so that he perceives light vibrations as sounds, and tremors of the air-as colors: he hears light and sees sound. This is also what happens in Kabuki! We actually "hear m0vement" and "see sound."

loading...

An example : Yuranosuke leaves the surrendered castle. And moves from the depth of the stage towards the extreme foreground. Suddenly the background screen with its gate painted in natural dimensions ( close-up) is folded away. In its place is seen a second screen, with a tiny gate painted on it (long shot). This means that he has moved even further away. Yuranosuke continues on. Across the background is drawn a brown-green-black curtain, indicating: the castle is now hidden from his sight. More steps. Yuranosuke now moves out on to the "flowery way." This further removal is emphasized by... the samisen, that is-by sound! !

First removal-steps, i.e., a spatial removal by the actor.

Second removal-a flat painting: the change of backgrounds. Third removal-an intellectually-explained indication: we understand that the curtain "effaces" something visible. Fourth removal-sound!

Here is an example of pure cinematographic method from the last fragment of Chushingura:

After a short fight ( "for several feet") we have a "break" an empty stage, a landscape. Then more fighting. Exactly as if, in a film, we had cut in a piece of landscape to create a mood in a scene, here is cut in an empty nocturnal snow landscape (on an empty stage). And here after several feet, two of the "forty-seven faithful" observe a shed where the villain has hidden (of which the spectator is already aware). Just as in cinema, within such a sharpened dramatic moment, some brake has to be applied. In Potemkin, after the preparation for the command to "Fire!" on the sailors covered by the tarpaulin, there are several shots of "indifferent" parts of the battleship before the final command is given: the prow, the gun-muzzles, a life-preserver, etc. A brake is applied to the action, and the tension is screwed tighter.

The moment of the discovery of the hiding-place must be accentuated. To find the right solution for this moment, this accent must be shaped from the same rhythmic material-a return to the same nocturnal, empty, snowy landscape ...

But now there are people on the stage! Nevertheless, the Japanese do find the right solution-and it is a flute that enters triumphantly! And you see the same snowy fields, the same echoing emptiness and night, that you heard a short while before, when you looked at the empty stage ...

Occasionally (and usually at the moment when the nerves seem about to burst from tension) the Japanese double their effects. With their mastery of the equivalents of visual and aural images, they suddenly give both, "squaring" them, and brilliantly calculating the blow of their sensual billiard-cue on the spectator's cerebral target. I know no better way to describe that combination, of the moving hand of Ichikawa Ennosuke as he commits hara-kiri-with the sobbing sound offstage, graphically corresponding with the movement of the knife. There it is: "Whatever notes I can't take with my voice, I'll show with my hands! " But here it was taken by the voice and shown with the hands! And we stand benumbed before such a perfection of-montage.

We all know those three trick questions: What shape is a winding staircase? How would you describe "compactly"?

What is a "surging sea"? One can't fonnulate intellectually analyzed answers to these. Perhaps Baudouin de Courtenay knows, but we are forced to answer with gestures. We show the difficult concept of "compactly" with a clenched fist, and so on.

And what is more, such a description is fully satisfactory . We also are slightly Kabuki! But not sufficiently!

In our "Statement" on the sound film we wrote of a contrapuntal method of combining visual and aural images. To possess this method one must develop in oneself a new sense: the capacity of reducing visual and aural perceptions to a "common denominator."

This is possessed by Kabuki to perfection. And we, too crossing in turn the successive Rubicons flowing between theater and cinema and between cinema and sound-cinema must also possess this. We can learn the mastery of this required new sense from the Japanese. As distinctly as impressionism owes a debt to the Japanese print, and post-impressionism to Negro sculpture, so the sound film will be no less obliged to the Japanese.

And not to the Japanese theater, alone, for these fundamental features, in my opinion, profoundly penetrate all aspects of the Japanese world-view. Certainly in those incomplete fragments of Japanese culture accessible to me, this seems a penetration to their very base.

We need not look beyond Kabuki for examples of identical perceptions of naturalistic three-dimensionality and flat painting. "Alien? " But it is necessary for this pot to boil in its own way before we can witness the completely satisfactory resolution of a waterfall made of vertical lines, against which a silverpaper serpentine fish-dragon, fastened by a thread, swims desperately. Or, folding back the screen-walls of a strictly cubist tea-house "of the vale of fans," a hanging backdrop is disclosed, a "perspective" gallery racing obliquely down its center. Our theater design has never known such decorative cubism, nor such primitivism of painted perspective. Nor, moreover, such simultaneity-here, apparently, pervading everything.

Costume. In the Dance of the Snake Odato Goro enters, bound with a rope that is also expressed, through transfer, in the robe's pattern of a flat rope-design, and her sash, as well, is twisted into a three-dimensional rope-a third form.

Writing. The Japanese masters an apparently limitless quantity of hieroglyphs. Hieroglyphs developed from conventionalized features of objects, put together, express concepts, i.e., the picture of a concept-an ideogram. Alongside these exists a series of Europeanized phonetic alphabets: the Manyo kana, hiragana, and others. But the Japanese writes all letters, employing both forms at once! It is not considered remarkable to compose sentences of hieroglyph pictures concurrently with the letters of several absolutely opposed alphabets. Poetry. The tanka is an almost untranslatable form of lyrical epigram of severe dimension: 5, 7, 5 syllables in the first strophe (kami-no-ku) and 7, 7 syllables in the second (shimo-no-ku)...This must be the most uncommon of all poetry, in both form and content. When written, it can be judged both pictorially and poetically. Its writing is valued no less as calligraphy than as a poem.

And content? One critic justly says of the Japanese lyric: "A Japanese poem should be sooner seen [i.e., represented visually.-S.E.] than heard."

APPROACH OF WINTER

They leave for the East A flying bridge of magpies A stream across the sky . . . The tedious nights Will be trimmed with hoar-frost.

Across a bridge of magpies in flight, it seems that Yakamochi (who died in 785) departs into the ether.

CROW IN THE SPRING MIST

The crow perched there Is half-concealed By the kimono of fog... As is a silken songster By the folds of the sash.

The anonymous author ( ca. 1800) wishes to express that the crow is as incompletely visible through the morning mist as is the bird in the pattern of the silk robe, when the sash is wound around the robed figure.

Strictly limited in its number of syllables, calligraphically charming in description and in comparison, striking in an incongruity that is also wonderfully near (crow, half-hidden by the mist, and the patterned bird, half-hidden by the sash), the Japanese lyric evidences an interesting "fusion" of images, which appeals to the most varied senses. This original archaic "pantheism" is undoubtedly based on a non-differentiation of perception-a well-known absence of the sensation of "perspective." It could not be otherwise. Japanese history is too rich in historical experience, and the burden of feudalism, though overcome politically, still runs like a red thread through the cultural traditions of Japan. Differentiation, entering society with its transition to capitalism and bringing in its wake, as a consequence of economic differentiation, differentiated perceptions of the world,-is not yet apparent in many cultural areas of Japan. And the Japanese continue to think "feudally," i.e., undifferentiatedly. This is found in children's art. This also happens to people cured of blindness where all the objects, far and near, of the world, do not exist in space, but crowd in upon them closely.

In addition to Kabuki, the Japanese also showed us a film, Karakuri-musume. But in this, non-differentiation, brought to such brilliant unexpectedness in Kabuki, is realized negatively.

Karakuri-musume is a melodramatic farce. Beginning in the manner of Monty Banks, it ends in incredible gloom, and for long intervals is criminally torn in both directions.

The attempt to tie these opposing elements together is generally the hardest of tasks. Even such a master as Chaplin, whose fusion of these opposing elements in The Kid is unsurpassed, was unable in The Gold Rush to balance these elements. The material slid from plane to plane. But in Karakuri-musume there is a complete smash-up.

As ever the echo, the unexpected junction, is found only at polar extremes. The archaism of non-differentiated sense "provocations" of Kabuki on one side, and on the other-the acme of montage thinking.

Montage thinking-the height of differentiatedly sensing and resolving the "organic" world-is realized anew in a mathematic faultlessly performing instrument-machine. Recalling the words of Kleist, so close to the Kabuki theater, which was born from marionettes:

... [grace] appears best in that human bodily structure which has no consciousness at all, or has an infinite consciousness-that is, in the mechanical puppet, or in the god.

Extremes meet ....

Nothing is gained by whining about the soullessness of Kabuki or, still worse, by finding in Sadanji's acting a "confirmation of the Stanislavsky theory"! Or in looking for what "Meyerhold hasn't yet stolen"!

Let us rather - hail the junction of Kabuki and the soundfilm!

SERGEI EISENSTEIN/Film Form: Essays in Film Theory/The Unexpected

Copyright 1949 by Harcourt, Brace & Horld, Inc. Copyright renewed 1977 by Jay Leyda

loading...

0 Comments

IT IS interesting to retrace the different paths of today's cinema workers to their creative beginnings, which together compose the multi-colored background of the Soviet cinema. In the early 1920's we all came to the Soviet cinema as something not yet existent. We came upon no ready-built city; there were no squares, no streets laid out; not even little crooked lanes and blind alleys, such as we may find in the cinemetropolis of our day. We came like bedouins or goldseekers to a place with unimaginably great possibilities, only a small section of which has even now been developed.

We pitched our tents and dragged into camp our experiences in varied fields. Private activities, accidental past professions, unguessed crafts, unsuspected eruditions-all were pooled and went into the building of something that had, as yet, no written traditions, no exact stylistic requirements, nor even formulated demands.

Without going too far into the theoretical debris of the specifics of cinema, I want here to discuss two of its features. These are features of other arts as well, but the film is particularly accountable to them. Primo: photo-fragments of nature are recorded; secundo: these fragments are combined in various ways. Thus, the shot (or frame), and thus, montage.

Photography is a system of reproduction to fix real events and elements of actuality. These reproductions, or photoreflections, may be combined in various ways. Both as reflections and in the manner of their combination, they permit any degree of distortion-either technically unavoidable or deliberately calculated. The results fluctuate from exact naturalistic combinations of visual, interrelated experiences to complete alterations, arrangements unforeseen by nature, and even to abstract formalism, with remnants of reality.

The apparent arbitrariness of matter, in its relation to the status quo of nature, is much less arbitrary than it seems. The final order is inevitably determined, consciously or unconsciously, by the social premises of the maker of the filmcomposition. His class-determined tendency is the basis of what seems to be an arbitrary cinematographic relation to the object placed, or found, before the camera.

We should like to find in this two-fold process (the fragment and its relationships) a hint as to the specifics of cinema, but we cannot deny that this process is to be found in other art mediums, whether close to cinema or not (and which art is not close to cinema?). Nevertheless, it is possible to insist that these features are specific to the film, because film-specifics lie not in the process itself but in the degree to which these features are intensified.

The musician uses a scale of sounds; the painter, a scale of tones; the writer, a row of sounds and words-and these are all taken to an equal degree from nature. But the immutable fragment of actual reality in these cases is narrower and more neutral in meaning, and therefore more flexible in combination, so that when they are put together they lose all visible signs of being combined, appearing as one organic unit. A chord, or even three successive notes, seems to be an organic unit. Why should the combination of three pieces of film in montage be considered as a three-fold collision, as impulses of three successive images?

A blue tone is mixed with a red tone, and the result is thought of as violet, and not as a "double exposure" of red and blue. The same unity of word fragments makes all sorts of expressive variations possible. How easily three shades of meaning can be distinguished in language-for example: "a window without light," "a dark window," and "an unlit window."

Now try to express these various nuances in the composition of the frame. Is it at all possible?

If it is, then what complicated context will be needed in order to string the film-pieces onto the film-thread so that the black shape on the wall will begin to show either as a "dark" or as an "unlit" window? How much wit and ingenuity will be expended in order to reach an effect that words achieve so simply?

The frame is much less independently workable than the word or the sound. Therefore the mutual work of frame and montage is really an enlargement in scale of a process microscopically inherent in all arts. However, in the film this process is raised to such a degree that it seems to acquire a new quality.

The shot, considered as material f or the purpose of composition, is more resistant than granite. This resistance is specific to it. The shot's tendency toward complete factual immutability is rooted in its nature. This resistance has largely determined the richness and variety of montage forms and styles-for montage becomes the mightiest means for a really important creative remolding of nature.

Thus the cinema is able, more than any other art, to disclose the process that goes on microscopically in all other arts.

The minimum "distortable" fragment of nature is the shot; ingenuity in its combinations is montage.

Analysis of this problem received the closest attention during the second half-decade of Soviet cinema (1925 - 1930), an attention often carried to excess. Any infinitesimal alteration of a fact or event before the camera grew, beyond all lawful limit, into whole theories of documentalism. The lawful necessity of combining these fragments of reality grew into montage conceptions which presumed to supplant all other elements of film-expression.

Within normal limits these features enter, as elements, into any style of cinematography. But they are not opposed to nor can they replace other problems-for instance, the problem of story.

To return to the double process indicated at the beginning of these notes: if this process is characteristic of cinema, finding its fullest expression during the second stage of Soviet cinema, it will be rewarding to investigate the creative biographies of film-workers of that period, seeing how these features emerged, how they developed in pre-cinema work. All the roads of that period led towards one Rome. I shall try to describe the path that carried me to cinema principles.

Usually my film career is said to have begun with my production of Ostrovsky's play, Enough Simplicity in Every Sage, at the Proletcult Theatre (Moscow, March 1923). This is both true and untrue. It is not true if it is based solely on the fact that this production contained a short comic film made especially for it (not separate, but included in the montage plan of the spectacle). It is more nearly true if it is based on the character of the production, for even then the elements of the specifics mentioned above could be detected.

We have agreed that the first sign of a cinema tendency is one showing events with the least distortion, aiming at the factual reality of the fragments. A search in this direction shows my film tendencies beginning three years earlier, in the production of The Mexican (from Jack London's story). Here, my participation brought into the theater "events" themselves-a purely cinematographic element, as distinguished from "reactions to events"-which is a purely theatrical element. This is the plot: A Mexican revolutionary group needs money for its activities. A boy, a Mexican, offers to find the money. He trains for boxing, and contracts to let the champion beat him for a fraction of the prize. Instead he beats up the champion, winning the entire prize. Now that I am better acquainted with the specifics of the Mexican revolutionary struggle, not to mention the technique of boxing, I would not think of interpreting this material as we did in 1920, let alone using so unconvincing a plot.

The play's climax is the prize-fight. In accordance with the most hallowed Art Theatre traditions, this was to take place backstage (like the bull-fight in Carmen), while the actors on stage were to show excitement in the fight only they can see, as well as to portray the various emoti?ns of the persons concerned in the outcome.

My first move (trespassing upon the director's job, since I was there in the official capacity of designer only) was to propose that the fight be brought into view. Moreover I suggested that the scene be staged in the center of the auditorium to re-create the same circumstances under which a real boxing match takes place. Thus we dared the concreteness of factual events. The fight was to be carefully planned in advance but was to be utterly realistic.

The playing of our young worker-actors in the fight scene differed radically from their acting elsewhere in the production. In every other scene, one emotion gave rise to a further emotion (they were working in the Stanislavsky system), which in turn was used as a means to affect the audience; but in the fight scene the audience was excited directly.

While the other scenes influenced the audience through intonation, gestures, and mimicry, our scene employed realistic, even textural means-real fighting, bodies crashing to the ring floor, panting, the shine of sweat on torsos, and finally, the unforgettable smacking of gloves against taut skin and strained muscles. Illusionary scenery gave way to a realistic ring (though not in the center of the hall, thanks to that plague of every theatrical enterprise, the fireman) and extras closed the circle around the ring.

Thus my realization that I had struck new ore, an actualmaterialistic element in theater. In The Sage, this element appeared on a new and clearer level. The eccentricity of the production exposed this same line, through fantastic contrasts. The tendency developed not only from illusionary acting movement, but from the physical fact of acrobatics. A gesture expands into gymnastics, rage is expressed through a somersault, exaltation through a salto-mortale, lyricism on "the mast of death." The grotesque of this style permitted leaps from one type of expression to another, as well as unexpected intertwinings of the two expressions. In a later production, Listen, Moscow (summer 1923), these two separate lines of "real doing" and "pictorial imagination" went through a synthesis expressed in a specific technique of acting.

These two principles appeared again in Tretiakov's Gas Masks (1923-24), with still sharper irreconcilability, broken so noticeably that had this been a film it would have remained, as we say, "on the shelf."

What was the matter? The conflict between materialpractical and fictitious-descriptive principles was somehow patched up in the melodrama, but here they-broke up and we failed completely. The cart dropped to pieces, and its driver dropped into the cinema. This all happened because one day the director had the marvelous idea of producing this play about a gas factory in a real gas factory. As we realized later, the real interiors of the factory had nothing to do with our theatrical fiction. At the same time the plastic chaml of reality in the factory became so strong that the element of actuality rose with fresh strength-took things into its own hands-and finally had to leave an art where it could not command.

Thereby bringing us to the brink of cinema. But this is not the end of our adventures with theater work. Having come to the screen, this other tendency flourished, and became known as "typage." This "typage" is just as typical a feature of this cinema period as "montage." And be it known that I do not want to limit the concept of "typage" or "montage" to my own works.

I want to point out that "typage" must be understood as broader than merely a face without make-up, or a substitution of "naturally expressive" types for actors. In my opinion, "typage" included a specific approach to the events embraced by the content of the fihn. Here again was the method of least interference with the natural course and combinations of events. In concept, from beginning to end, October is pure "typage."

A typage tendency may be rooted in theater; gro\ving out of the theater into film, it presents possibilities for excellent stylistic growth, in a broad sense-as an indicator of definite affinities to real life through the camera.

And now let us examine the second feature of film-specifics, the principles of montage. How was this expressed and shaped in my work before joining the cinema?

In the midst of the flood of eccentricity in The Sage, including a short film comedy, we can find the first hints of a sharply expressed montage. The action moves through an elaborate tissue of intrigue. Mamayev sends his nephew, Glumov, to his wife as guardian. Glumov takes liberties beyond his uncle's instructions and his aunt takes the courtship seriously. At the same time Glumov begins to negotiate for a marriage with Mamayev's niece, Turussina, but conceals these intentions from the aunt, Mamayeva. Courting the aunt, Glumov deceives the uncle; flattering the uncle, Glumov arranges with him the deception of the aunt. Glumov, on a comic plane, echoes the situations, the overwhelming passions, the thunder of finance, that his French prototype, Balzac's Rastignac, experiences. Rastignac's type in Russia was still in the cradle. Money-making was still a sort of child's game between uncles and nephews, aunts and their gallants. It remains in the family, and remains trivial. Hence, the comedy. But the intrigue and entanglements are already present, playing on two fronts at the same time-with both hands-with dual characters . . . and we showed all this with an intertwined montage of two different scenes (of Mamayev giving his instructions, and of Glumov putting them into execution). The surprising intersections of the two dialogues sharpen the characters and the play, quicken the tempo, and multiply the comic possibilities.

For the production of The Sage the stage was shaped like a circus arena, edged with a red barrier, and three-quarters surrounded by the audience. The other quarter was hung with a striped curtain, in front of which stood a small raised platform, several steps high. The scene with Mamayev (Shtraukh) took place downstage while the Mamayeva (Yanukova) fragments occurred on the platform. Instead of changing scenes, Glumov (Yezikanov) ran from one scene to the other and back-taking a fragment of dialogue from one scene, interrupting it with a fragment from the other scene-the dialogue thus colliding, creating new meanings and sometimes wordplays. Glumov's leaps acted as caesurae between the dialogue fragments.

And the "cutting" increased in tempo. What was most interesting was that the extreme sharpness of the eccentricity was not torn from the context of this part of the play; it never became comical just for comedy's sake, but stuck to its theme, sharpened by its scenic embodiment.

Another distinct film feature at work here was the new meaning acquired by common phrases in a new environment.

Everyone who has had in his hands a piece of film to be edited knows by experience how neutral it remains, even though a part of a planned sequence, until it is joined with another piece, when it suddenly acquires and conveys a sharper and quite different meaning than that planned for it at the time of filming.

This was the foundation of that wise and wicked art of reediting the work of others, the most profound examples of which can be found during the dawn of our cinematography, when all the master film-editors-Esther Schub, the Vassiliyev brothers, Benjamin Boitler, and Birrois - were engaged in reworking ingeniously the films imported after the revolution.

I cannot resist the pleasure of citing here one montage tour de force of this sort, executed by Boitler. One film bought from Germany was Danton, with Emil Jannings. As released on our screens, this scene was shown: Camille Desmoulins is condemned to the guillotine. Greatly agitated, Danton rushes to Robespierre, who turns aside and slowly wipes away a tear. The sub-title said, approximately, "In the name of freedom I had to sacrifice a friend..." Fine.

But who could have guessed that in the German original, Danton, represented as an idler, a petticoat-chaser, a splendid chap and the only positive figure in the midst of evil characters, that this Danton ran to the evil Robespierre and ...spat in his face? And that it was this spit that Robespierre wiped from his face with a handkerchief? And that the title indicated Robespierre's hatred of Danton, a hate that in the end of the film motivates the condemnation of Jannings-Danton to the guillotine?!

Two tiny cuts reversed the entire significance of this scene!

Where did my montage experiment in these scenes of The Sage come from?

There was already an "aroma" of montage in the new "left" cinema, particularly among the documentalists. Our replacement of Glumov's diary in Ostrovsky's text with a short "film-diary" was itself a parody on the first experiments with newsreels.

I think that first and foremost we must give the credit to the basic principles of the circus and the music-hall-for which I had had a passionate love since childhood. Under the influence of the French comedians, and of Chaplin (of whom we had only heard), and the first news of the fox-trot and jazz, this early love thrived.

The music-hall element was obviously needed at the time for the emergence of a "montage" form of thought. Harlequin's parti-colored costume grew and spread, first over the structure of the program, and finally into the method of the whole production.

But the background extended more deeply into tradition. Strangely enough, it was Flaubert who gave us one of the finest examples of cross-montage of dialogues, used with the same intention of expressive sharpening of idea. This is the scene in Madame Bovary where Emma and Rodolphe grow more intimate. Two lines of speech are interlaced: the speech of the orator in the square below, and the conversation of the future lovers:

Monsieur Derozerays got up, beginning another speech . .. praise of the Government took up less space in it; religion and agriculture more. He showed in it the relations of these two, and how they had always contributed to civilization. Rodolphe with Madame Bovary was talking dreams, presentiments, magnetism. Going back to the cradle of society, the orator painted those fierce times when men lived on acorns in the heart of woods. Then they had left off the skins of beasts, had put on cloth, tilled the soil, planted the vine. Was this a good, and in this discovery was there not more of injury than of gain? Monsieur Derozerays set himself this problem. From magnetism little by little Rodolphe had come to affinities, and while the president was citing Cincinnatus and his plough, Diocletian planting his cabbages, and the Emperors of China inaugurating the year by the sowing of seed, the young man was explaining to the young woman that these irresistible attractions find their cause in some previous state of experience.

"Thus we," he said, "why did we come to know one another? What chance willed it? It was because across the infinite, like two streams that flow but to unite, our special bents of mind had driven us towards each others."

And he seized her hand; she did not withdraw it.

"For good farming generally!" cried the president. "Just now, for example, when I went to your house." "To Monsieur Bizat of Quincampoix." "Did I know I should accompany you? " "Seventy francs." "A hundred times I wished to go; and I followed you-I remained." "Manures!" "And I shall remam to-night, to-morrow, all other days, all my life!"

And so on, with the "pieces" developing increasing tension.

As we can see, this is an interweaving of two lines, thematically identical, equally trivial. The matter is sublimated to a monumental triviality, whose climax is reached through a continuation of this cross-cutting and word-play, with the significance always dependent on the juxtaposition of the two lines.

Literature is full of such examples. This method is used with increasing popularity by Flaubert's artistic heirs.

Our pranks in regard to Ostrovsky remained on an "avant garde" level of an indubitable nakedness. But this seed of montage tendencies grew quickly and splendidly in P atatra, which remained a project through lack of an adequate hall and technical possibilities. The production was planned with "chase tempos," quick changes of action, scene intersections, and simultaneous playing of several scenes on a stage that surrounded an auditorium of revolving seats. Another even earlier project attempted to embrace the entire theater building in its composition. This was broken up during rehearsals and later produced by other hands as a purely theatrical conception. It was the Pletnev play, Precipice, which Smishlayev and I ,vorked on, following The Mexican, until we disagreed on principles and dissolved our partnership. (When I returned to Proletcult a year later, to do The Sage, it was as a director, although I continued to design my own productions.)

Precipice contains a scene where an inventor, thrilled by his new invention, runs, like Archimedes, about the city (or perhaps he was being chased by gangsters-I don't remember exactly). The task was to solve the dynamics of city streets, as well as to show the helplessness of an individual at the mercy of the "big city." (Our mistaken imaginings about Europe naturally led us to the false concept of "urbanism.")

An amusing conlbination occurred to me, not only to use running scenery-pieces of buildings and details ( Meyerhold had not yet worked out, for his Trust D. E., the neutral polished shields, murs mobiles, to unify several places of action)-but also, possibly under the demands of shifting scenery, to connect these moving decorations with people. The actors on roller skates carried not only themselves about the stage, but also their "piece of city." Our solution of the problem-the intersection of man and milieu-was undoubtedly influenced by the principles of the cubists. But the "urbanistic" paintings of Picasso were of less importance here than the need to express the dynamics of the city-glimpses of facades, hands, legs, pillars, heads, domes. All of this can be found in Gogol's work, but we did not notice that until Andrei Belyi enlightened us about the special cubism of Gogol. I still remember the four legs of two bankers, supporting the facade of the stock-exchange, with two top-hats crowning the whole. There was also a policeman, sliced and quartered with traffic. Costumes blazing with perspectives of twirling lights, with only great rouged lips visible above. These all remained on paper-and now that even the paper has gone, we may become quite pathetically lyrical in our reminiscences.

These close-ups cut into views of a city become another link in our analysis, a film element that tried to fit itself into the stubborn stage. Here are also elements of double and multiple exposure-"superimposing" images of man onto images of buildings-all an attempt to interrelate man and his milieu in a single complicated display. (The fact that the film Strike was full of this sort of complexity proves the "infantile malady of leftism" existing in these first steps of cinema.)

Out of mechanical fusion, from plastic synthesis, the attempt evolves into thematic synthesis. In Strike, there is more than a transformation into the technique of the camera. The composition and structure of the film as a whole achieves the effect and sensation of uninterrupted unity between the collective and the milieu that creates the collective. And the organic unity of sailors, battleships, and sea that is shown in plastic and thematic cross-section in Potemkin is not by trickery or double-exposure or mechanical intersection, but by the general structure of the composition. But in the theater, the impossibility of the mise-en-scene unfolding throughout the auditorium, fusing stage and audience in a developing pattern, was the reason for the concentrated absorption of the mise-en-scene problems within the scenic action.

The almost geometrically conventional mise-en-scene of The Sage and its formal sequel, Listen, Moscow, becomes one of the basic elements of expression. The montage intersection eventually became too emphatically exact. The composition singled out groups, shifted the spectator's attention from one point to another, presented close-ups, a hand holding a letter, the play of eyebrows, a glance. The technique of genuine mise-en-scene composition was being mastered-and approaching its limits. It was already threatened with becoming the knight'S move in chess, the shift of purely plastic contours in the already non-theatrical outlines of detailed drawings.

Sculptural details seen through the frame of the cadre, or shot, transitions from shot to shot, appeared to be the logical way out for the threatened hypertrophy of the mise-en-scene. Theoretically it established our dependence on mise-en-scene and montage. Pedagogically, it determined, for the future, the approaches to montage and cinema, arrived at through the mastering of theatrical construction and through the art of mise-en-scene. Thus was born the concept of mise-en-cadre. As the mise-en-scene is an interrelation of people in action, so the mise-en-cadre is the pictorial composition of mutually dependent cadres (shots) in a montage sequence.

In Gas Masks we see all the elements of film tendencies meeting. The turbines, the factory background, negated the last remnants of make-up and theatrical costumes, and all elements appeared as independently fused. Theater accessories in the midst of real factory plastics appeared ridiculous. The element of "play" was incompatible with the acrid smell of gas. The pitiful platform kept getting lost among the real platforms of labor activity. In short, the production was a failure. And we found ourselves in the cinema.

Our first film opus, Strike [1924-25], reflected, as in a mirror, in reverse, our production of Gas Masks. But the film floundered about in the flotsam of a rank theatricality that had become alien to it.

At the same time, the break with the theater in principle was so sharp that in my "revolt against the theater" I did away with a very vital element of theater-the story. At that time this seemed natural. We brought collective and mass action onto the screen, in contrast to individualism and the "triangle" drama of the bourgeois cinema. Discarding the individualist conception of the bourgeois hero, our films of this period made an abrupt deviation-insisting on an understanding of the mass as hero. No screen had ever before reflected an image of collective action. Now the conception of "collectivity" was to be pictured. But our enthusiasm produced a one-sided representation of the masses and the collective; one-sided because collectivism means the maximum development of the individual within the collective, a conception irreconcilably opposed to bourgeois individualism. Our first mass films missed this deeper meaning.

Still, I am sure that for its period this deviation was not only natural but necessary. It was important that the screen be first penetrated by the general image, the collective united and propelled by one wish. "Individuality within the collective," the deeper meaning, demanded of cinema today, would have found entrance almost impossible if the way had not been cleared by the general concept.

In 1924 I wrote, with intense zeal: "Down with the story and the plot!" Today, the story, which then seemed to be almost "an attack of individualism" upon our revolutionary cinema, returns in a fresh form, to its proper place. In this tum towards the story lies the historical importance of the third half-decade of Soviet cinematography (1930-1935). And here, as we begin our fourth five-year period of cinema, when abstract discussions of the epigones of the "story" film and the embryones of the "plotless" film are calming down, it is time to take an inventory of our credits and debits. I consider that besides mastering the elements of filmic diction, the technique of the frame, and the theory of montage, we have another credit to list-the value of profound ties with the traditions and methodology of literature. Not in vain, during this period, was the new concept of film-language born, film-language not as the language of the film-critic, but as an expression of cinema thinking, when the cinema was called upon to embody the philosophy and ideology of the victorious proletariat. Stretching out its hand to the new quality of literature-the dramatics of subject-the cinema cannot forget the tremendous experience of its earlier periods. But the way is not back to them, but forward to the synthesis of all the best that has been done by our silent cinematography, towards a synthesis of these with the demands of today, along the lines of story and Marxist-Leninist ideological analysis. The phase of monumental synthesis in the images of the people of the epoch of socialism-the phase of socialist realism.

SERGEI EISENSTEIN/Film Form: Essays in Film Theory/Through Theater To Cinema

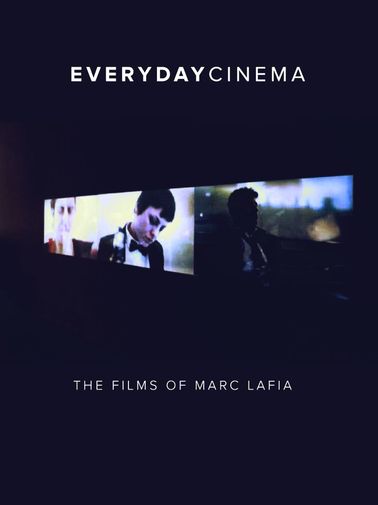

Copyright 1949 by Harcourt, Brace & Horld, Inc. Copyright renewed 1977 by Jay Leyda The Extraordinary Event of Everyday Cinema: On the Films by Marc Lafia  Everyday Cinema presents the films (eight components and various shorts, computational, and installation movies) of Marc Lafia. In his many movies (counting Exploding Oedipus; Love and Art; Confessions of an Image; Revolution of Everyday Life; Paradise; Hi, How Are You Guest 10497; and 27) Lafia tests what it is to develop a picture, to fashion frameworks of portrayal, to see and speak to ourselves. His work has been characterized as a film of rise, a silver screen of the occasion, in which the very demonstration of universal recording makes something new. Everyday Cinema is comprised of two parts, the initial an inside and out take a gander at his movies and establishments, extend by venture, giving foundation on how they came to fruition, Lafia's procedure and thoughts. The second part highlights chose interviews and more than two hundred film stills wherein Lafia advances another feeling of the likelihood of the silver screen. As we as a whole steadily record ourselves and are recorded, we turn out to be a piece of the artistic texture of life, some portion of a scene of which we are both constituent and constitutive. This is the thing that Lafia embarks to catch and look at. Cinema is no longer gigantic. In spite of the best endeavors of Hollywood, making a film no longer requests a huge number of dollars, blasts, grasps, lights, and cameras. We needn't bother with theaters. We needn't bother with studios. All we need is a cell phone. Cinema has become everyday. Marc Lafia has taken to making movies that grasp the everyday cinema machine. He has a thought; assembles a cast (he has begun working with similar on-screen characters); and movies in the city of New York with computerized cameras. In his most recent, The Revolution of Everyday Life, he gives HD Flip camcorders to the cast and has them film themselves alone. For Lafia, this procedure is not an economical approach to make ta so-called indie film with its idiosyncratic characters and accounts of reclamation. This is not mumblecore. Nor is it The Blair Witch Project or Mean Streets For Lafia, the ordinary apparatuses of silver screen breed a rising film, a film of the occasion, in which the very demonstration of recording makes something new. The most obvious and fascinating thing about viewing a Marc Lafia film is that it's plainly up to something. This is an alternate sort of cinema. Indeed, even the routes in which it difficulties are not well known. Without a doubt, the movies are liberal, abundant, and delightful—however in the meantime, they solicit odd things from us. But then what makes them so odd is definitely their everydayness, their careful engagement with the devices and means we as a whole know so well—just we don't expect them in our "films." There's something uncanny going ahead here. We watch videos throughout the day on YouTube, Facebook, Vine, Vimeo. The recorded moving picture has moved from over yonder, up on the extra large screen, to ideal here, before me, at all circumstances. Recording has turned out to be universal, organized, and computational. But then our cinema stays, generally, univocal and grand. Movies today may incorporate pervasive recording as something to speak to—think about the Jason Bourne movies or Catfish—yet those movies themselves stay amazing instead of computational and arranged. The dependably on recording of the social Web is generally changing our method for remaining toward the picture, toward ourselves, toward each other. But with regards to watching "motion pictures," we have altogether different desires—not simply as far as art or quality but rather as far as what considers genuine, as scene, as screen, as filmic occasion. As a prepared producer who once made component movies, Lafia has most likely been managed new strategies and obvious flexibilities by new media. He needn't bother with six truckloads of blasts, links, and grasps—also a truckload of cash. He has a thought; assembles a cast; and movies wherever he is—generally the boulevards of New York. Regularly, he has performing artists film themselves all alone, outfitted with some sort of directions and a little HD camera. His procedure is open yet correct, to some degree "scripted," continually creating, conforming to situation. Be that as it may, this is not an economical approach to make a supposed outside the box film with peculiar characters and recovery accounts. This is not an approach to make a film for next to nothing and maintain a strategic distance from the Hollywood scramble for cash. For Lafia, new media implies better approaches for going. In the expressions of Deleuze and Guattari, new media offer a line of flight from the state device of the film business. The ordinary devices of film breed an alternate sort of silver screen, with various account methodologies, distinctive thoughts of character, an alternate transaction of thoughts, scene, and even screen. Lafia's movies don't as much utilize or hold onto new media as they are of this everyday cinema. This is not just another method for recording: it is a recoding—of cinema, of story, of self, of life. In the event that we live in a general public of the scene, this everyday cinema motor decenters picture generation, multiplies focuses, smashs the authority of the partnership's will to amount and consistency. This inescapability of cinema — this capacity to make, convey, and screen on request — in a general sense shifts streams of correspondence, presenting radical new potential outcomes of constituting the social. Pictures no longer exclusively stream downhill or in a straight direct line. They are no longer exclusively made by immense companies and gushed into our homes. Pictures now stream each which path — up, down, sideways, corner to corner — disturbing the excruciating platitude of account, character and buzzword. As cinema takes up the everyday, it imbues life and is thus implanted. Drawing in this regular film motor, Lafia gives us a living cinema, a live cinema, a film that is dependably (and right now) during the time spent making itself, a cinema loaded with influence, with the incomprehensible many-sided quality of the human: a cinema that is progressive.  Marc Lafia is an artist, filmmaker, photographer, curator, educator, essayist and information architect. Lafia's profession as a artist started in the mid 1980s in filmmaking. Lafia's many works incorporate appointed movies, online works, and multi-screen computational installations for the Walker Art Center; the Whitney Museum of American Art; Tate Online: Intermedia Art; Zentrum für Kunst und Medientechnologie (ZKM), Karlsruhe, Germany; NTT InterCommunication Center (ICC), Tokyo; and Center Georges Pompidou. Marc has lectured and taught courses on film directing, acting for the camera, new media art practices, and graduate seminars in new media philosophy, methods, and practices at Stanford University, San Francisco Art Institute, California Institute of the Arts, Pratt Institute of Design, and Art Center College of Design in Pasadena, California, New York Film Academy, and Columbia University. His essays on the subjects of new media art, computational cinema, and the way of the picture have been published in Artforum International, Digital Creativity, Eyebeam.org, and Film and Philosophy Journal. Museums of contemporary art, including the Museum of Modern Art-New York; the Tate Britain's online online for-profit dare, Tate Online: Intermedia Art; and the Institute of Contemporary Art, Boston utilized Lafia’s expertise as a creative strategist and information architect to conduct global media audits of best practices in advance technologies for the arts, and audits of each institution’s assets for online initiatives. Marc Lafia lives in Brooklyn, New York.

Life as a reflection, life as a dream

Andrei Arsenevich Tarkovsky (1932–1986) was a Soviet film director, writer, and theorist. His family had a literary background, and he studied art, music and language at school.

Andrei Tarkovsky (1932-1986) directed seven feature films and three student shorts over a 24-year period. Ivanovo detstvo (Ivan’s Childhood, 1962), Andrei Rublev (1966) and Solaris (1972); Zerkalo (Mirror) (1975)after it, will come Stalker (1979), Nostalghia (1983) and Offret (The Sacrifice, 1986). The last two – shot in Italy and Sweden, respectively – were made in exile from the Soviet Union. "Tarkovsky is for me the greatest, the one who invented a new language, true to the nature of film, as it captures life as a reflection, life as a dream." - Ingmar Bergman

The great Swedish director Ingmar Bergman excellently intoned in his 1987 autobiography, “The Magic Lantern,” that discovering Russian filmmaker Andrei Tarkovsky’s work was, “A miracle. Tarkovsky for me is the greatest director, the one who invented a new language, true to the nature of film, as it captures life as a reflection, life as a dream.”

In 1987, a couple of months after Tarkovsky's passing Akira Kurosawa would praise his “unusual sensitivity as both overwhelming and astounding. It almost reaches a pathological intensity. Probably there is no equal among film directors alive now.” And trial movie producer Stan Brakhage was essentially stricken, pursuing him down at the Telluride Film Festival in 1983 to screen his work and calling him, “the greatest living narrative filmmaker.”

Awards for Tarkovsky, one of Russia's most persuasive filmmakers are for the most part gleaming praises, motivating a zest that would discover the faction chief's work inspected and contemplated for quite a long time. In any case, similarly passionate are his spoilers; gatherings of people and faultfinders who locate his moderate, sluggish, mysterious work exhausting and invulnerable. Such uncontrollably dissimilar venerate him-or-despise him sentiments must mean a certain something: that Tarkovsky's movies speak to the apotheosis of a specific sort of filmmaking and eventually your inclination to like that sort of film conditions your response to Tarkovsky. Indeed, even the individuals who loathe moderate, thoughtful, dreamlike movies can't prevent Tarkovsky's authority from claiming the frame. Furthermore, with film history continually in a condition of modification, Tarkovsky's work, such as streaming water searching for an exit, dependably discovers roads for re-appreciation. This week, Kino International discharges his last picture, "The Sacrifice" on Blu-Ray, and prior this year in May, the Criterion Collection — which has three of his movies in their list — released his science fiction great, "Solaris" onto the Blu-design.

Interminably intrigued by the spiritual, the metaphysical, the texture of dreams and memory, Tarkovsky shunned customary account and plot, and rather looked to light up the pith of the oblivious through a patient, puzzling and intelligent silver screen that for some outskirts on lovely heavenliness.

While their methods and aesthetics are unmistakably unique, one marvels why Terrence Malick's movies and comparative huge picture reflections seldom come up in discussions about Tarkovsky. There seems to be a sure family relationship between their work, however it's impossible the Russian filmmaker could ever have condescended to incorporate a voiceover that actually asks each mystical question out loud; it was more his style to represent these regularly existential conundrums verifiably, letting the imagery do the work, quietly, dreamily.

Making just seven features in twenty-four years, Tarkovsky permitted his movies to inhale, to say the least — they are frequently portrayed by their extreme length ("Andrei Rublev" is 3 hours and 25 minutes), their unhurried pace and the utilization of amplified following shots that could last from 7-10 minutes, all of which continually loaned his photos a lethargic, hallucinatory, sleep inducing environment. Tarkovsky trusted silver screen was the main artistic expression that could genuinely save the stream of time — which maybe clarifies the length of his movies to some degree — and keeping in mind that his mesmeric dream tenor and narcotic pacing can send the normal moviegoer off to rest, his "chiseling of time" ethos (the name of his posthumous 1989 book) for the most part motivates stunningness, ponder and a feeling of lovely equivocalness in those with persistence and interest enough to give themselves over to the experience.

As John Gianvito place it in his 2006 Tarkovsky Interviews book, the corpus of his work is the “near-messianic pursuit of nothing less than the redemption of the soul of man.”

The historical backdrop of the silver screen has seen executives whose works have been more "unique" or "noteworthy, (for example, Eisenstein, Ozu or Godard). Furthermore, there are a lot of chiefs who have made the same number of, if not more movies (Griffith, Hitchcock or Chabrol). However the question remains: is there any individual who so typifies the idea of the auteur – a movie producer with full control over his medium, whose work has an unmistakable and incomparable mark – as Ingmar Bergman?

One reason one promptly perceives a Bergman film is that he is one of those uncommon movie producers who has made his own true to life world. (This is likewise the reason that we have a segment on this site under the heading Universe.) Through repeating situations, topics, characters, expressive gadgets, performing artists and film groups, Bergman has made his own sort of film, right around a class in itself. On the off chance that Alfred Hitchcock is the encapsulation of the mental thriller (regardless of the way that he likewise made movies in different types), Bergman has turned into the trademark for the existential/philosophical relationship show (in spite of the fact that he, as well, has made different sorts of movies). Without disparaging the effect of Ingmar Bergman's own work, his standing has additionally been impacted by various outside components. He composed his first screenplay toward the finish of the Second World War, and began to make his own movies amid the post war years. As far as film history, this was a period of radical change (with winning styles, for example, Italian neo-authenticity and film noir in the USA) which has once in a while, to some degree delicately maybe, been alluded to as a watershed amongst "great" and "current" movies. For Bergman's situation, nonetheless, no such division can completely be said to exist. His movies regularly (yet not generally) utilize the story methods of "exemplary" film with the expansion of "current" expressive gadgets. On the off chance that Bergman's introduction came amid a time of real change in silver screen history, his worldwide leap forward came only before the begin of another such period. It is not really an occurrence that it was in France in the mid 1950s that Bergman got his first certified acknowledgment outside Sweden. The "New Wave" was going to break, and growing chiefs like Jean-Luc Godard and Eric Rohmer were persuasive film faultfinders who proclaimed Bergman, up until then moderately obscure, as the "world's principal executive". Simply, Bergman fitted in flawlessly with the perfect they wished to advance: the auteur who utilizes the film camera as an essayist uses his pen. In this shape Bergman's movies quickly came to exemplify the idea of "craftsmanship house silver screem". In a period when film was at the end of the day taking a stab at authenticity, Bergman exhibited that film could be something more than amusement: it could without a doubt be workmanship. All things considered, recollect that Bergman instantly went before the other "advanced" European chiefs with whom he is frequently said: Antonioni, Buñuel, Fellini, Godard and others. The way that film considers developed toward the finish of the 1960s as a scholastic teach in its own privilege is in many regards down to Bergman, whose movies of existential investigation actually loan themselves to methodical examination. To a vast degree, Bergman's subjects established the framework for his notoriety. His Strindberg-like conviction that marriage äktenskapet is terrible, and his repeating questions about God gudstvivlet were, incidentally enough, and to put it roughly, very little more than a synopsis of the Scandinavian social custom at the time, with its sprouting sexual flexibility and its effectively broad secularization. However abroad at the time, not minimum in the catholic European and South American nations, or in the ethically traditionalist United States and Eastern Europe, Bergman's movies seemed progressive. Neither would one be able to thoroughly disregard the commitment to Bergman's accomplishment of what were, for the time, very brave portrayals of bareness and "regular" sexuality. Bergman' movies, with their incredible dialect, scenes of pristine common magnificence orörd natur and blonde ladies blonda kvinnor, were broadly viewed as the epitome of a Scandinavian sort of exoticism. On the off chance that one disregards the encompassing variables that added to the effect of Ingmar Bergman and looks rather at what makes his movies one of a kind, one can start to recognize the topical and complex improvements of his profession. Albeit any endeavor to compartmentalize any craftsman's oeuvre is of need a rearrangements, one can in any case separation Bergman's film creation generally into five periods. Such a division into periods requires a specific measure of oversight (and indeed, the periods are frequently entwined), however it provides a depiction of his improvement. Focus on young lovers

Concentrate on youthful partners, particularly from the common laborers. Frequently set in the city and its environment (the Stockholm Archipelago). Clear impacts from neo-authenticity, particularly Roberto Rossellini. Memory is a vital expressive gadget. Much of the time utilized performing artists incorporate Alf Kjellin, Birger Malmsten, Maj-Britt Nilsson and Stig Olin. Cinematographers were generally Göran Strindberg and Gunnar Fischer. Different organizations lay behind the creations: Svensk Filmindustri, Sveriges Folkbiografer and Terrafilm.

Focus on marriage

Concentrate on marriage, frequently with the lady in the focal part. Settings are frequently ordinary, either cutting edge urban communities or common situations of times past. True to life good examples have all the earmarks of being Mauritz Stiller or Ernst Lubitsch's room comedies, Alfred Hitchcock's specialized abilities and Jean Renoir's investigates of average lip service. Gunnar Fischer is only the cinematographer of decision. Throws were enrolled from his general work environment at the time, Malmö City Theater: Harriet Andersson, Gunnar Björnstrand, Eva Dahlbeck and Åke Grönberg. Bergman moved between two generation organizations: Sandrews and Svensk Filmindustri.

The most imperative movies of the period are Waiting Women, A Lesson in Love and his first universal achievement, Smiles of a Summer Night. Essential movies of this period are Torment (for which Bergman just composed the screenplay), his presentation film Crisis, Prison (his first film with his own particular screenplay), Summer Interlude (which as indicated by Bergman himself was the first of his "own" movies) and Summer With Monika. Metaphysics and human

Concentrate on anxiety ridden male focal characters. Settings progressively include fruitless scenes, independent of whether the movies are set in cutting edge times or, as in two cases, in the Middle Ages. In spite of noteworthy contrasts, the religious issues displayed in the movies have all the earmarks of being enlivened by film chiefs Carl Theodor Dreyer and Robert Bresson. Memory keeps on having a critical influence, and Bergman's most imperative elaborate commitment to film history starts to rise unequivocally: the uncompromising utilization of the nearby up. Gunnar Fischer proceeds as his cinematographer until 1961, when Sven Nykvist assumes control. His gathering of performing artists is currently totally settled with Malmö City Theater keeping on providing names, for example, Bibi Andersson, Ingrid Thulin and Max von Sydow. A companion from his initial years, Erland Josephson starts to assume minor parts. Bergman works only with Svensk Filmindustri.

All of Bergman's best known movies are made amid this period: The Seventh Seal, Wild Strawberries and the supposed "hush of God set of three": Through a Glass Darkly, Winter Light and The Silence. In the event that one likewise includes his broad work in the theater, this is without a doubt the imaginative high purpose of Bergman's vocation. Imperative movies of this period are Torment (for which Bergman just composed the screenplay), his presentation film Crisis, Prison (his first film with his own screenplay), Summer Interlude (which as per Bergman himself was the first of his "own" movies) and Summer With Monika. The role of the artist and woman

The movies are set solely on the fruitless Baltic Sea island of Fårö (where Bergman makes his home), and the social setting is middle class. The period is Bergman's most trial, with pioneer components. Close-ups command the symbolism in a way unparalleled somewhere else in film history. The most imperative on-screen characters stay, as some time recently, Bibi Andersson, Erland Josephson and Max von Sydow, with the essential presentation of Liv Ullmann. Sven Nykvist is dependably the cinematographer, and Svensk Filmindustri the creation organization until the mid 1970s, when Bergman set up his own particular organization, Cinematograph. In the vicinity of 1976 and 1981 he makes movies abroad (Germany, Norway), yet for the most part in Swedish.

The period sees the two movies which many (counting Bergman himself) view as his most imperative of all: Persona and Cries and Whispers. Other vital works incorporate the fruitful TV arrangement Scenes From a Marriage and the film just perceived as of late, the German dialect From the Life of the Marionettes. Epilog and collection of memoirs

Amid Bergman's later period his movies are generally worried with an intelligent summing up both of his prior profession and his own particular life. Past topics, for example, marriage, religion and the part of the craftsman repeat: even past characters re-rise. His movies are made only for TV. Vital parts are played by Erland Josephson and Liv Ullmann, additionally by new performing artists for Bergman, for example, Börje Ahlstedt. He likewise composes screenplays for other individuals; the subjects are his own existence of those of his folks, and the executives are regularly individuals with individual associations with himself, for example, his child Daniel Bergman, or his previous accomplice Liv Ullmann.

The period's real film in all regards is Fanny and Alexander, yet After the Rehearsal, In the Presence of a Clown and Saraband likewise rate profoundly in Bergman's later filmography. This division into periods above has its impediments. Certain subjects, for instance, first seem sooner than they are said above, and vital movies, for example, Sawdust and Tinsel or The Magician don't fit easily into the example. However as a fundamental outline of Bergman's movie profession, it additionally has its qualities. An exceptionally critical executive, Ingmar Bergman today appears to be unexpectedly to have been for all intents and purposes overlooked. His effect has been so all-unavoidable, his impact so extraordinary and his movies such evident benchmarks, that his work has nearly turned out to be undetectable. However similarly as one every so often needs to return to the Bible to comprehend something of western culture, one needs to see Bergman's movies over again. For some it was quite a while prior; for others it will be interestingly. Whichever it is, the movies will feel natural.

“I think it's important that we all try to give something to this medium, instead of just thinking about what is the most efficient way of telling a story or making an audience stay in a cinema.”

His genuine name is Lars Trier - he included the "von" on for impact at film school. Clearly in tribute to executive Josef von Sternberg, and his Teutonic fixation at film school, the highborn "von" is an expansion. Interestingly enough, a number of the coaches at his Danish Film School thought he was an egomaniac without ability who might go no place.

He has a productive and disputable vocation spreading over very nearly four decades. His work is known for its kind and specialized development, angry examination of existential, social, and political issues, and treatment of subjects like benevolence, give up and emotional wellness. His political and helpful work was respected in 2004 with the Cinema for Peace mindfulness grant. Among more than 100 honors and more than 200 assignments in celebrations around the world, he has gotten the Palme d'Or (for Dancer in the Dark), the Grand Prix (for Breaking the Waves), the Prix du Jury (for Europa), and the Technical Grand Prize (for The Element of Crime and Europa) at the Cannes Film Festival. In 2016 Trier started shooting The House that Jack Built, an English-dialect serial executioner thriller. Lars von Trier is the organizer and shareholder of worldwide film generation organization Zentropa Films,[16][17] which has sold more than 350 million tickets and accumulated seven Academy Award designations in the course of recent years. Career

Von Trier went to the National Film School of Denmark, graduating in 1983. He was conceived Lars Trier, yet while in school he included the prefix von—generally a marker of participation in the gentry—to his surname trying to be provocative.

Von Trier started his profession with the wrongdoing film Forbrydelsens component (1984; The Element of Crime), the first in an inevitable arrangement known as the Europa set of three, which gorgeously investigates confusion and estrangement in current Europe. Alternate movies in the set of three are Epidemic (1987), a metafictional purposeful anecdote about a torment, and Europa (1991; discharged in the U.S. as Zentropa), an examination of life in post-World War II Germany. In 1994 von Trier composed and coordinated a Danish TV miniseries called Riget (The Kingdom), which was set in a clinic and concentrated on the extraordinary and horrifying. It demonstrated so prevalent that it was trailed by a spin-off, Riget II (1997), and later roused an American form, adjusted by American awfulness writer Stephen King, for which von Trier served as official maker. In 1995 von Trier and Danish chief Thomas Vinterberg composed a statement for an idealist film development called Dogme 95. Taking an interest chiefs took what the gathering named the Vow of Chastity, which bound them to a rundown of fundamentals that, in addition to other things, disallowed the utilization of any props or impacts not characteristic to the film's setting with a specific end goal to accomplish a direct type of story based authenticity. Von Trier's next film was Breaking the Waves (1996), an inauspicious story about a devout Scottish lady subjected to severity that was tied down by a bravura Oscar-selected execution by Emily Watson. It encapsulates a great part of the soul of Dogme 95, however it was not actually confirmed in that capacity. At last, the main authority Dogme 95 film that von Trier coordinated was Idioterne (1998; The Idiots), an exceedingly disputable work that focuses on a gathering of individuals who openly put on a show to be formatively incapacitated.

In 2000 von Trier released Dancer in the Dark, a drama that elements Icelandic pop vocalist Björk as an about visually impaired assembly line laborer who discovers help from her consistent travails in dream powered melodic numbers. Von Trier pulled in further consideration for Dogville (2003), a critical and drastically stark illustration about the United States, featuring Nicole Kidman. Despite the fact that it was reprimanded for its absence of nuance and for its sex governmental issues, the film was taken after two years by a spin-off, Manderlay. Later movies incorporate Antichrist (2009), which unsettled groups of onlookers with its realistic delineation of sexual brutality inside a lamenting couple's relationship, and the frightful Melancholia (2011), in which a clamorous wedding and orderly familial strife are set against a planet's approaching crash with Earth. His next film, Nymphomaniac, was discharged in two volumes (2013). It chronicled the lewd exercises of a solitary lady—played by a few performers at various ages—from her first encounters to her later rendezvous. The film was exceedingly questionable in view of its delineation of unsimulated sex acts.

Aesthetics, lemma and style of working

To simplify Danish film history perhaps a bit unfairly, one could claim that only two directors really matter – Carl Theodor Dreyer and Lars von Trier. The two gentlemen are groundbreaking innovators, preeminent auteurs, towering over a scene of good humored people satire and polite standard authenticity. Dreyer and von Trier, producers of dull true to life workmanship, are related spirits with a solid creative association. Von Trier has, obviously, been granted the Carl Th. Dreyer Prize – in 1995, the 100th commemoration of film.

Additionally, Dreyer and von Trier have in like manner a practically whimsical separation from the thunderings of the nearby resound chamber. It ought to be noted, be that as it may, that there is no partner to von Trier's Dogme development in Dreyer: no school ever conformed to Dreyer.

As far back as the start of von Trier's profession, he held up Dreyer as his venerated image of profound respect, which shaded some of his soonest creations. Through his maternal uncle, the narrative movie producer Børge Høst, youthful von Trier landed a position at the recent Statens Filmcentral, which managed him the chance to view Dreyer's La Passion de Jeanne d'Arc endless circumstances on the altering table. The motivation from Dreyer is very evident in von Trier's first driven creations, Orchidégartneren (1978) and Menthe – la bienheureuse (1979), two half-hour movies made on a beginner premise while he was in the Film Studies program at Copenhagen University in 1976-79. Uninhibitedly propelled by the sexual novel Story of O, the Menthe film incorporates torment scenes with chains shot in a whitewashed room that are near the torment scenes in Jeanne d'Arc. In addition, Dreyer and von Trier have in like manner a practically flighty separation from the thunderings of the nearby reverberate chamber. It ought to be noted, nonetheless, that there is no partner to von Trier's Dogme development in Dreyer: no school ever conformed to Dreyer.

Medea – Directed by von Trier from a Dreyer Script