|

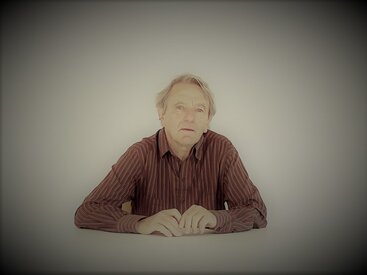

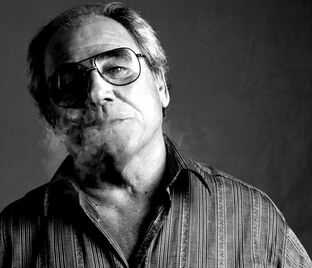

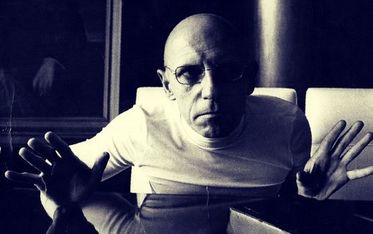

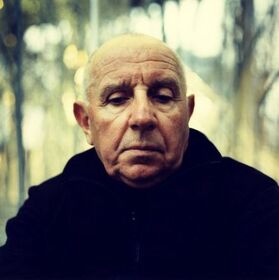

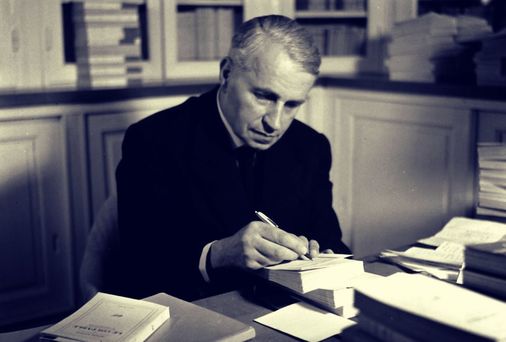

This interview was conducted in Paris on 29 August 2002. Peter Hallward: One of your constant concerns has been to analyse and condemn any posture of mastery, particularly theoretical, pedagogical, “academic” mastery. So may I ask why you started teaching? How did you first get involved with education? Jacques Rancière: I became involved almost unwittingly, when I went through the École Normale Supérieure (ENS), which was set up to train teachers. I am, in the first instance, a student. I am one of those people who is a perpetual student and whose professional fate, as a consequence, is to teach others. “Teaching” obviously implies a certain position of mastery, “researcher” implies in some way a position of knowledge, “teacher-researcher” implies the idea of the teacher adapting a position of institutional mastery to one of mastery based on knowledge. At the outset, I was immersed in an Althusserian milieu, and consequently marked by its idea of forms of authority linked specifically to knowledge. But I was also caught up in the whole period of 1968, which threw into question the connection between positions of mastery and knowledge. I went through it all with the mentality of a researcher: I thought of myself, above all, as someone who did research and let others know about his research. Which meant, for example, that as a teacher I always resisted divisions into levels (advanced, intermediate, etc.). At the University of Paris VIII, where I have taught for most of my career, there were no levels in the philosophy department and I have always tried hard to maintain this lack of division into levels. In my courses I often have people of all different levels, in the belief that each student does what he or she can do and wants to do with what I say. P.H.: I suppose you must have made your initial decision to take up teaching and research path at about the age of fifteen or sixteen: did you grow up in a milieu where this option was encouraged? J.R.: As a child, I wanted to go to the ENS because I wanted to be an archaeologist. But by the time I got into the ENS I’d lost that sense of vocation. It has to be said, too, that this was a time when, for people like me, there wasn’t really much of a choice: you were good in either arts or sciences. And if you were good in arts, you aimed for what was considered the best in the field, which is to say, the ENS. That, rather than any vocation to teach, is how I ended up there. P.H.: And your initial collaboration with Althusser, was it a true conversion or the result of a theoretical interest? What happened at that point? J.R.: Several things happened. First, there was my interest in Marxism, which was not at all part of the world I’d been brought up in. For people like me, our interest in Marxism before Althusser had to follow some slightly unorthodox paths. The people who had written books on Marx, the authorities on Marx at the time, were priests like Father Calvez, who had written a hefty book on Marx’s thought, or people like Sartre. So, I arrived at Marxism with a sort of Marxian corpus which was hardly that of someone from the communist tradition, but which did provide access to Marx at a time when he didn’t have a university presence and when theory was not very developed within the French Communist Party. In relation to all that, Althusser represented a break. People told me about him when I first entered the ENS: they said he was brilliant. He really did offer a way of breaking with the Marxist humanist milieu in which we had been learning about Marx at the time. So, of course, I was enthusiastic, because Althusser was seductive, and I was working against myself in a way, because following Althusser’s thinking meant breaking with the sort of Marxism that I had known, that I was getting to know, and with those forms of thought that did not share its sort of theoretical engagement. P.H.: Would it be too simple to say that Althusser was a teacher, whereas Sartre was something else – not a researcher or a teacher, but a writer or an intellectual, I guess? J.R.: I don’t know if you can say “teacher.” In the end, Althusser taught relatively little. His words seduced us, but they were those of certain written texts as much as anything oral. He was like the priest of a religion of Marxist rigour, or of the return to the text. It wasn’t really the rigour of his teaching that appealed so much as an enthusiasm for his declaration that there was virgin ground to be opened up. His project to read Capital was a little like that: the completely naive idea that we were pioneers, that no one had really read Marx before and that we were going to start to read him. So there were two sides to our relation with Althusser. There was, first of all, a sense of going off on an adventure: for the seminar on Capital, I was supposed to talk, to explain to people the rationality of Capital, when I still hadn’t read the book. So I rushed about, rushed to start reading the various volumes of Capital, in order to be able to talk to others about them. There was this adventurous side, but there was something else as well: our roles as pioneers put us in a position of authority, it gave us the authority of those who know, and it instituted a sort of authority of theory, of those who have knowledge, in the midst of a political eclecticism. Thus, there was an adventurous side and a dogmatic side to it all, and they came together: the adventure in theory was at the same time dogmatism in theory. P.H.: It’s the role of the pioneer you’ve held on to. Did your break with Althusser take place during the events of May 1968? What happened exactly? J.R.: For me, the key moment wasn’t the events of May 1968, which I watched from a certain distance, but rather the creation of Paris VIII. With the creation of a philosophy department full of Althusserians, we had to decide what we were going to do. It was then I realised that Althusser stood for a certain power of the professor, the professor of Marxism who was so distant from what we had seen taking place in the student and other social movements it was almost laughable. At the time, what really made me react was a programme for the department put together by Etienne Balibar, a programme to teach people theoretical practice as it should be taught. I came out rather violently against this programme, and from that point began a whole retrospective reflection on the dogmatism of theory and on the position of scholarly knowledge we had adopted. That’s more or less how things started for me, not with the shock of 1968 but with the aftershock. Which is to say, with the creation of an institution, an institution where we were, in one sense, the masters. It was a matter of knowing what we were going to do with it, how we were going to manage this institutional mastery, if we were going to identify it with the transmission of science or not. P.H.: How did that work at Paris VIII? How did you bring the rather anarchic side of egalitarian teaching together with the institutional necessity of granting degrees, verifying qualifications, etc.? J.R.: At the time, I had thought very little about an alternative pedagogical practice. I had more or less given up on philosophy, the teaching of philosophy, and academic practice. What seemed important was direct political practice, so for a time I stopped reflecting on and thinking of myself as creating a new pedagogical practice or a new type of knowledge. This was linked to the fact that the diploma in philosophy at Paris VIII was quickly invalidated. We no longer gave national diplomas, so we were no longer bound by the criteria needed to award them. For a good while, then, I was absolutely uninterested in rethinking pedagogy: I was thinking, first, of militant practice and then, when that was thrown into question, of my practice as a researcher. For years my main activity was consulting archives and going to the Bibliothèque Nationale. My investment in the practice of teaching was fairly limited. P.H.: Did your courses continue more or less as usual, that is, as lectures? J.R.: Not entirely. It varied: there were lectures, but there were also courses which took the form of conversations and interventions. P.H.: La Leçon d’Althusser [1974] insists on the urgency of the time, a time full of possibilities, when it was still possible to present Marxism as a way of thinking an imminent victory. When you started to work on the nineteenth century and on proletarian thinking in the 1830s and 1840s, was that partly to compensate for philosophical defeat in the present? J.R.: I don’t think so. In the beginning, mine was a fairly naive approach: to try to understand what the words “workers’ movement,” “class consciousness,” “workers’ thought,” and so on really meant, and what they concealed. Basically, it was clear that the Marxism we had learned at school and had seen practised by Marxist organisations was a long way from the reality of forms of struggle and forms of consciousness. I wanted to construct a genealogy of that difference. P.H.: A difference that begins in the moment just before Marx? J.R.: What I wanted to do, starting out from the present, from 1968 (and from what had been proved inappropriate not only by Althusserianism and the Communist Party but also by the movements of the Left more generally), was to rewrite the genealogy of the previous century and a half. In particular, I wanted to return to the moment of Marxism’s birth to try to mark the difference between Marxism and what could have been an alternative workers’ tradition. This project soon swerved off course. Initially it was a matter of searching for genuine forms of workers’ thinking, a genuine workers’ movement. In relation to Marxism, then, mine was a rather identitarian perspective. But the more I worked the more I realised that what was at issue was precisely a form of movement that broke with the very idea of an identitarian movement. Being a “worker” wasn’t in the first instance a condition reflected in forms of consciousness or action; it was a form of symbolisation, the arrangement of a certain set of statements or utterances. I became interested in reconstituting the world that made these utterances [énonciations] possible. P.H.: Many of your contemporaries abandoned Marxism rather quickly, having come to the conclusion that the proletariat – as the universal subject of an eventually singular history, the class that incarnates the dissolution of class – seemed to lead more or less directly to the Gulag. You, on the other hand, continued to reflect on the proletariat in its singularity, but by resituating it in an historical sequence that seemed better able to anticipate the risks of dogmatism and dictatorship. It was still a question of a universal singularity, but a singularity in some sense absent from itself, a deferred, differentiated singularity. J.R.: In the end, what interested me was a double movement, the movement of singularisation and its opposite. On the one hand, there was a movement away from the properties that characterised the worker’s being and the forms of statement that were supposed to go along with that condition. On the other hand, this withdrawal itself created forms of universalisation, forms of symbolisation which also constituted the positivity of a figure. What interested me was always this play between negativation and positivation. I was interested in thinking it through as an impossible identification, since the intellectual revolution in question here was, in the first instance, a work of disidentification. The proletarians of the 1830s were people seeking to constitute themselves as speaking beings, as thinking beings in their own right. But this effort to break down the barrier between those who think and those who don’t came to constitute a sort of shared symbolic system, a system forever threatened by new positivation. As a result, you could no longer say that there had been an authentic workers’ movement somewhere, one that had managed to escape all forms of positivation and deterioration. I wanted to show that these forms of subjectivation or disidentification were always at risk of falling into an identitarian positivation, whether that was a corporative conception of class or the glorious body of a community of producers. It wasn’t a matter of opposing a true proletariat to some corporatist degeneration or to the Marxists’ proletariat; rather, I wanted to show how the figure of subjectivation itself was constantly unstable, constantly caught between the work of symbolic disincorporation and the constitution of new bodies. P.H.: Sometimes you present political practice as a sort of ex nihilo innovation, almost like the constitution of a new world, even if the world in question is extremely fragile, uncertain, ephemeral. Don’t you need to consider political innovation alongside the development of its conditions of possibility? I mean, for instance, on the political side of things, the role played by civic institutions and state organisations, the public space opened up, in Athens, in France, by the invention of democratic institutions (that is, the sort of factors you generally relegate to the sphere of the police, as opposed to the sphere of politics). And on the linguistic side of things, I’m thinking of some sort of preliminary equality of competences, a basic sharing of the symbolic domain. Such might be the objection of someone working in the Habermasian tradition. In short, which comes first: the people or the citizen? J.R.: I don’t know if you can say that one of those comes before the other, because so many of these things work retroactively. There is an inscription of citizenship because there is a movement which forces this inscription, but this movement to force inscription almost always refers back to some sort of pre-inscription. Men who are free and equal in their rights are always supposed already to exist in order that their existence can be proclaimed and their legal inscription enforced. I would say, though, that this equality or legal freedom produces nothing in itself. It exists only in so far as it defines a possibility, in so far as there is an effective movement which can grasp it and bring it into existence retroactively. For me the question of a return to origins is hopeless. If we take modern democracy, it is clear it works by recourse to an earlier inscription. There is always an earlier inscription, be it 1789, the American or English Revolution, Christianity, or the ancient city-state; as a result, the question of origins doesn’t really come up. As to the origin of origins, you can conceive it in different ways: it could be an originary anthropology of the political, but I know I don’t have the means or tools to think of it this way. It could be a transcendental condition, but, for me, this transcendental condition can work only as a process of retroactive demonstration. I don’t have any answers as to real, actual origins, and I don’t think you can set out something like a transcendental condition for there being people in general. P.H.: Nonetheless, you insist on an equality that exists once people speak, once they say to themselves they are equal as people who speak. Doesn’t this equality, however, establish at the very same time the conditions of an inequality between people who speak more or less well? An abstract equality between players taking part in the same game and following the same rules always exists, but obviously that doesn’t stop there being winners and losers. Is it a matter of a real equality or some sort of inclusion presupposed by participation in the game (which, in the end, is less a matter of equality than of formal similarity)? J.R.: It isn’t a formal similarity. Rather, it is the necessity of some minimal equality of competence in order for the game to be playable. As I said when I went back to Joseph Jacotot [discussed in detail in The Ignorant Schoolmaster (1987)] in Disagreement (1995): for an order to be transmitted and executed there has to be a minimal level of linguistic equality. This is the problem that troubles Aristotle: slaves need to understand what they are told. Aristotle gets around it by saying that the slave participates in language by understanding it but not possessing it. He discerns a kind of hard kernel in the possession of language, which he opposes to its simple use. But what is this possession, this hexis, which he opposes to the simple fact of understanding? He never explains it. I don’t have an irenic understanding of language as some sort of common patrimony which allows everyone to be equal. I’m just saying that language games, and especially language games that institute forms of dependence, presume a minimal equality of competence in order that inequality itself can operate. That’s all I’m saying. And I say this not to ground equality but to show, rather, how this equality only ever functions polemically. If it is a transcendental category, its only substance lies in the acts which make manifest its effectiveness. P.H.: Isn’t there a quasi-transcendental or at least transhistorical aspect to your idea that the political actor, the universal actor, is always to be found on the side of those who aren’t accounted for in the organisation of society? Politics as you conceive it always concerns the mobilisation of those who aren’t included in the social totality, who constitute a part of society which groups those who belong to no identifiable social part (or who have no particular share [part] of society) and who thus establish themselves as the incarnation of the universal interest. The examples you give (Athenian democracy, 1789, proletarian singularity, etc.), are they thus examples of a more general rule: that politics only happens when the excluded are able to affirm themselves in universal terms? What leads you to believe that this remains the rule in today’s and tomorrow’s political conflicts? It’s difficult to imagine a genuine conception of the universal in the USA today, for example, when people are so caught up in the conflict between the abstract power of the market and various communitarian and identitarian movements. J.R.: It isn’t a question of belief so much as of defining the political. There are clearly all sorts of government and many different modes of domination and management. If “politics” has a meaning, and a meaning that applies to everything we seek to elaborate as specifically political, for me its meaning is just this: there is a whole that constitutes itself other than as a collection of existing parts. For me, this is the only condition under which we can speak of politics. Which doesn’t stop there being states, communities, and collectivities, all of which operate according to their different logics. But we must distinguish this very specific form, where the capacity for power is attributed to those who have no particular ability to exercise it, where the accounting of the whole is dissociated from any organic conception, from the generality of forms of assembly, government, and domination. I think that the USA is indeed a barely political community. This doesn’t mean that there aren’t conflicts. But there is a whole structured system of being together which is not only thought but also massively practised in terms of belonging or membership (perhaps founded on sub-memberships), in terms of properties and rights attached to memberships, and so on. For me, all this defines an ethical rather than a political conception of community. This conception doesn’t necessarily have disastrous consequences, even though it seems to in the USA today. I see it as a question of definition: a community is political when it authorises forms of subjectivation for the uncounted, for those unaccounted for. This needn’t imply a visible category which identifies itself as “the excluded” and which wants to identify the community with itself – in that case we’d be back in ethics. I am simply saying that when there is a properly political symbolising of the community, then this, in the last instance, is where it lies. Inequality first takes effect as a miscounting or misaccounting, an inequality of the community to itself. Now as to the question: is politics still possible today? I would say that politics is always possible, there is no reason for it to be impossible. But is politics actually imminent? Here, obviously, I share your sadness, if not your pessimism, about the current state of public affairs. P.H.: There has often been, for instance, in the anti-colonial struggles, in the struggle for civil rights in the USA, a universalist moment, as you conceive it. This moment rarely lasts, however, and many Americans might say that under the circumstances there were good reasons to replace Martin Luther King with Malcolm X – in short, that in the reality of the struggle a choice had to be made: to adopt some sort of militant particularism or accept the effective end of the struggle. J.R.: I wouldn’t claim to advise American political movements, especially those that took place in the past. I think that we are always ambiguously placed, at constant risk of being coercively pinned down. Either you are taken in by a universal that is someone else’s, that is, you trust some idea of citizenship and equality as it operates in a society that in fact denies you these things, or you feel you must radically denounce the gap between idea and fact, usually by recourse to some identitarian logic. At this point, though, whatever you manage to achieve comes because you show yourself to belong to this identity. It’s very difficult, but I think that politics consists of refusing this dilemma and putting the universal under stress. Politics involves pushing both others’ universal and one’s own particularity to the point where each comes to contradict itself. It turns on the possibility of connecting the symbolic violence of a separation with a reclaiming of universality. The double risk of what goes by the name of liberalism still remains: on the one hand, submission to the universal as formulated by those who dominate; on the other hand, confinement within an identitarian perspective in those instances where the functioning of this universal is interrupted. No movement has really managed to avoid both risks altogether. P.H.: Does your idea of democracy presuppose democracy as it is supposed to have existed for several centuries, that is, where the place of power is in principle empty, such that it might be occupied, at least occasionally, by exceptional figures of universal interest? J.R.: I don’t think the place of power is empty. Unlike Claude Lefort, I don’t tie democracy to the theme of an empty place of power. Democracy is first and foremost neither a form of power nor a form of the emptiness of power, that is, a form of symbolising political power. For me, democracy isn’t a form of power but the very existence of the political (in so far as politics is distinct from knowing who has the right to occupy power or how power should be occupied), precisely because it defines a paradoxical power – one that doesn’t allow anyone legitimately to claim a place on the basis of his or her competences. Democracy is, first of all, a practice, which means that the very same institutions of power may or may not be accompanied by a democratic life. The same forms of parliamentary powers, the same institutional frameworks can either give rise to a democratic life, that is, a subjectivation of the gap between two ways of counting or accounting for the community, or operate simply as instruments for the reproduction of an oligarchic power. P.H.: It isn’t first and foremost a question of power? This is Slavoj Zizek’s objection, when he reads you (briefly) in his The Ticklish Subject [1999]: that you posit unrealistic, impossibly ideal conditions for political practice, and as a result end up just keeping your hands clean. How might we organise a true popular mobilisation without recourse to power, the party, authority, etc.? J.R.: I’m not saying you need absolutely no power. I’m not preaching spontaneity as against organisation. Forms of organisation and relations of authority are always being set up. The fact that I don’t much care for the practices of power and the forms of thought they engender is a secondary, personal concern. The central problem is theoretical. Politics may well have to do with powers and their implementation, but that doesn’t mean that politics and power are one and the same. The essential point is that politics cannot be defined simply as the organisation of a community. Nor can it be defined as the occupation of the place of government, which isn’t to say that this place doesn’t exist or doesn’t have to be occupied. It is the peculiar tendency of what I call the police to confuse these things. Politics is always an alternative to any police order, regardless of both the forms of power the former must develop and the latter’s organisation, form or value. P.H.: But, leaving aside the business of government, how are we to think the organisation of political authority in this sense? What sorts of organisation enable the insurrection of the excluded or the militant mobilisation of universal interest? It’s obvious you’re not a party thinker. But how are we to pursue a politics without party which will, nevertheless, remain a militant politics? Is this something that needs to be reinvented within each political episode? J.R.: I don’t think there are rules for good militant organisation. If there were, we’d already have applied them and we’d certainly be further along than we are at the moment. All I can define are forms of perception, forms of utterance. As to how these are then taken up by organisations, I must admit that I’ve never been able to endure any one of them for very long, but I know I have nothing better to propose. P.H.: Towards the end of Disagreement, I think, you say there was a genuine political movement in France at the time of the Algerian war, a subversive movement, that was clearly different from the movements of generalised “sympathy” which developed around the recent conflicts in Bosnia, Rwanda, and Timor. Can you see the beginnings of a new movement of this type, against the aggressor, in some currents of antiAmerican and anti-globalisation thinking? J.R.: That is difficult to define today. It’s easy to see that people are inspired by the dream of a political movement that would define itself in opposition to the domination of international capitalism. In reality, though, no political movement has yet defined itself against international capital. To this point they have been defined within national frameworks, or as relations between distinct peoples and their national states, or possibly as three-way relations, as was the case with Algeria and with the anti-imperialist struggles more generally. In such cases the national stage split on the international stage and allowed the uncounted to be accounted for. This threeway game, this political cause of the other, seems impossible today. The anti-globalisation movements want to take on capital as world government directly. But capital is precisely a government that isn’t one: it isn’t a state, and it doesn’t recognise any “people” inside or outside it who might serve as its point of reference or offer themselves for subjectivation. The idea of the multitude proposed by Negri and Hardt is a direct response to this absence of points at which political subjectivation might take hold. In the end, their idea rests on the transposition of a Marxian economic schema by which the forces of production break through the external framework of the relations of production. Capital escapes all political holds. The vast demonstrations of recent years have, in fact, sought to force it onto the political stage through the institutional or policing instruments by which it operates. The idea of a direct relation between the multitude and empire seems to me to bypass the problem of constituting a global political stage. I’m not sure that we will ever attain a directly political form of anti-capitalist struggle. I don’t think there can be an anti-imperialist politics which isn’t mediated by relations to states, bringing into play an inside and an outside. It’s easy to sense the difficulties that the anti-globalisation movements and their theorists have when it comes to current forms of imperialism – for example, with American politics after 11 September. It’s clear that the rules of the game are being mixed up today. At the time of the big anti-imperialist movements against the Vietnam War, for instance, we had a clear sense of who was the aggressor and who was under attack; we could play on the obvious contradiction between internal democratic discourse and external imperialist aggression. Again, when the USA supported such and such a dictatorship in the name of the struggle against communism, we could demonstrate the discrepancy between the declared struggle for democracy and the reality of supporting dictatorships. What has characterised the whole period after 11 September, however, has been the erasure of these signs of contradiction. The war in Afghanistan was presented directly as a war of good against evil. The contradictions between inside and outside, like those between words and deeds, have disappeared in favour of a general moralising of political life. The global reign of the economy is accompanied by a global reign of morality, in which it is harder for political action to find its stakes. P.H.: So, for you, national mediation remains essential and effective for the moment? J.R.: I think national mediation remains effective, yes, because it’s there that the relation between a structure of inclusion and what it excludes plays itself out. If lots of things are happening around those “without” – particularly around immigrants “without papers [sanspapiers]” – it is because the example of those without papers exposes the contradiction between affirming free circulation in a world without borders and the practices of keeping borders under surveillance and defining groups of people who cannot cross them. So, I think there are specific scenes of contradiction in confining some people while allowing others to circulate freely, but not one great nomadic movement of the multitude against empire or one overarching relation between the system and its peripheries. P.H.: A last question on politics. You say that “the essential work of politics is the configuration of its own space. It is to get the world of its subjects and its operations to be seen.” 2 You want to distinguish all political action – every instance of dissensus – from what you call the domain of the police, the domain of social coordination, the government, etc. But don’t we have to think of politics in relation to all the various ways that social inequality is structured, in relation, for example, to education, the organisation of urban life, conditions of employment, economic power, etc.? J.R.: There I think you’re attributing to me an idea that isn’t mine but Badiou’s. I think that it is indeed possible to define what is specific to politics, and in such a way as to separate political practice and the ideas of political community from all forms of negotiation between the interests of social groups. That’s why I say that the political isn’t the social. But I’d also say that the “social” as an historical configuration isn’t some sort of shameful empirical magma – situational,state-controlled, and so on (rather as Badiou imagines it) – which the political act would escape from. On the contrary, I think that the social is a complex domain, that what we call the social is a sort of mixture where the policing logics which determine how things are to be distributed or shared out among social groups encounter the various ways of configuring the common space which throw these same distributions into question. What we call “social benefits” are not only forms of redistributing national income; they are always also ways of reconfiguring what is shared or common. In the end, everything in politics turns on the distribution of spaces. What are these places? How do they function? Why are they there? Who can occupy them? For me, political action always acts upon the social as the litigious distribution of places and roles. It is always a matter of knowing who is qualified to say what a particular place is and what is done in it. So, I think that politics constantly emerges from questions traditionally thought of as social, that politics runs through labour movements and strikes, as well as around educational questions. You could say that the great political movements in France over the last twenty years have been connected with social questions, those of school and university, the status of employees, the sanspapiers or the unemployed – all fundamentally questions we might call social. But what does social mean? It means that what is at stake in institutional problems relating to school or nationality, or in problems arising around the distribution of work and wealth (employment or social benefits), is really the configuring of what is shared or common. I’m thinking, for example, of the movements in France that grew up around university selection in 1986, or around pensions and social benefits in the autumn of 1995. The battle over selection reminded us that the school and university system is not simply an instrument of “training” or “reproduction”; it is also the institution by which a society signifies to itself the meaning of the community that institutes it. In the same way, questions relating to pensions, health, and social security not only concern what are referred to as employees’ privileges and rights but also engage with the idea of the configuration of the common sphere. Whether healthcare and pensions operate by a system of redistribution and solidarity, or through individual private insurance, doesn’t just concern the privileges that employees may have acquired at any historical moment: it touches on the configuring of the common sphere. Within any so-called social negotiation there is always negotiation over what the community holds as common. P.H.: You quote Hannah Arendt from time to time: do you feel close to her conception of politics, politics as a place of negotiation, a place of performances and appearances (rather than timeless essences), of the vita activa valued above the pretensions of theory, philosophy, and the vita contemplativa? J.R.: Let’s say there’s some ground for agreement, coupled with a very strong disagreement (a disagreement which is also a reaction against the dominant uses and interpretations of her work today). The basis of agreement is that politics is a matter of appearance [apparence], a matter of constituting a common stage or acting out common scenes rather than governing common interests. That said, in Hannah Arendt this fundamental affirmation is linked to the idea that the political stage is blurred or cluttered by the claims of the social – I’m thinking of what she has to say about the French Revolution and the role of pity, where compassion for the “needy” clouds the purity of the political scene. To my mind this just returns us to some of the most traditional preconceptions about there being two distinct sorts of life: one able to play the political game of appearance and the other supposedly devoted to the sole reality of reproducing life. Her conception of political appearance simply mirrors the traditional (that is, Platonic) opposition, which reserves the legitimate use of appearance for one form of life alone. For me, by contrast, the appearance of the demos shatters any division between those who are deemed able and those who are not. Her opposition between the political and the social returns us to the old oppositions in Greek philosophy between men of leisure and men of necessity, the latter being men whose needs exclude them from the domain of appearance and, hence, from politics. A significant part of what I’ve managed to write about politics is a response to Hannah Arendt’s use, in On Revolution, of John Adams’s little phrase, that the misfortune of the poor lies in their being unseen. She says that such an idea could only have occurred to someone who was already a participant in the distinction of political life, that it cannot be shared by the poor in question, because they do not realise they are not seen – so a demand for visibility has no meaning for them. However, all my work on workers’ emancipation showed that the most prominent of the claims put forward by the workers and the poor was precisely the claim to visibility, a will to enter the political realm of appearance, the affirmation of a capacity for appearance. Hannah Arendt remains a prisoner of the tautology by which those who “cannot” think a thing do not think it. As I understand it, though, politics begins exactly when those who “cannot” do something show that in fact they can. That is the theoretical differend. As for practice, Arendt’s distinction between the political and the social has been widely used (during the events of December 1995 to justify governmental policies, for example). “Liberals” and “republicans” keep on reciting their Hannah Arendt to show that politics – which is to say, the state and the government – is above social pettiness, a realm of common collective interests that transcends corporate egoisms. P.H.: Michelet figures prominently in your The Names of History [1992]. Did his conception of history as the history of collective liberty, of a people becoming conscious of itself, the story of a hitherto silent people’s entry into speech, inspire you in one way or another? And what is Michelet’s relation, say, to the egalitarian thought of a Jacotot (as you describe it in The Ignorant Schoolmaster)? J.R.: I wanted, above all, to show how Michelet had invented a new form of mastery, one based on anonymous collective speech. It’s the Romantic thesis of a speech that is supposed to come from below in opposition to the dominant, noisy voices of the day. But Michelet never lets this speech from below actually be spoken, in its own terms. He converts the speech of revolutionary assemblies into a kind of discourse of the earth: a discourse of the fields or the city, of rural harvests or the mud in the streets, the silent word of truth as opposed to the actual words of speakers. What I tried to explain was the constitution of this paradigm of the silent masses (as distinct from the noisy people), the poetico-political paradigm of a great anonymous, unconscious thought expressing itself not through people’s words but through their silence, which then becomes a scientific paradigm in history and sociology. This wordless speech is something completely different from Jacotot and his affirmation of the capacity to speak of those who “don’t know how,” that is, his presupposition and verification of the equality of intelligences. There are two ways of thinking equality. It can be thought in terms of intellectual emancipation founded on the idea of man as a “literary animal” – an idea of equality as a capacity to be verified by anybody. Or it can be thought in terms of the indifferentiation of a collective speech, a great anonymous voice – the idea that speech is everywhere, that there is speech written on things, some voice of reality itself which speaks better than any uttered word. This second idea begins in literature, in Victor Hugo’s speech of the sewer that says everything, and in Michelet’s voice of the mud or the harvest. Later, this poetic paradigm becomes a scientific one. The obvious problem is that these two paradigms, these two ways of thinking the equality of the nameless, which are opposed in theory, keep mixing in practice, so that discourses of emancipation continually interweave the ability to speak demonstrated by anyone at all together with the silent power of the collective. P.H.: This is perhaps a good moment to move on to questions of aesthetics. Your book on Mallarmé came out in 1996, followed by La Parole muette in 1998. Since then you seem to have been working mainly on topics relating to art, literature, and aesthetics. Why the shift in interest? Was it something foreseen, something you had been anticipating? J.R.: I’ve never had a programme for the future, have never programmed my future projects. So, I’ve never imagined my work developing from politics to aesthetics, especially since it has always sought to blur boundaries. What I wanted to show when I wrote Nights of Labor [1981] was that a so-called political and social movement was also an intellectual and aesthetic one, a way of reconfiguring the frameworks of the visible and the thinkable. In the same way, in Disagreement I tried to show how politics is an aesthetic matter, a reconfiguration of the way we share out or divide places and times, speech and silence, the visible and the invisible. My personal interests have most often drawn me to literature and cinema, certainly more than to questions of socalled political science, which in themselves have never interested me very much. And if I was able to write on workers’ history it was because I always had in mind a whole play of literary references, because I saw workers’ texts through a number of models offered by literature, and because I developed a mode of writing and composition that allowed me to break, in practice, with the politics implicit in the traditional way of treating “workers’ speech,” as the expression of a condition. For me, the elaboration of a philosophical discourse or a theoretical scene is always also the putting into practice of a certain poetics. So, for me, there has never been a move from politics to aesthetics. Take the Mallarmé book, for example: what was the core of my interest in Mallarmé? Something like a community of scene [de scène]. The two prose poems in which Mallarmé stages the poet’s relation to the proletarian interested me initially because they replayed in a new way scenes that had already been acted out between proletarians and utopians. Even the relation between day and night in Mallarmé (which is generally understood through the themes of nocturnal anxiety and purity) reminded me strongly of why I had spoken of the nights of labour – not on account of workers’ misfortune, but in recognition of the fact that they annex the night, the time of rest, and thereby break the order of time which keeps them confined to a certain place. All this has always been absolutely connected for me,whether I take it as the aesthetics inherent in politics or the politics inherent in writing. Before Mallarmé, before La Parole muette, even before Disagreement, I led a seminar over several years on the politics of writing – that is, not on “how to write politics” but on “what is properly political in writing.” The work on Michelet was about the birth of a certain way of writing history. Does writing translate properties and transmit knowledge, or does it itself constitute an act, a way of configuring and dividing the shared domain of the sensible? These questions have continued to interest me. This politics of writing is, then, something completely different from the questions of representation by which politics and aesthetics are generally linked. Knowing how writers represent women, workers, and foreigners has never really interested me. My interest has always been in writing as a way of cutting up the universal singular. I’m thinking, for example, of Flaubert’s declarations, such as “I am interested less in the ragged than in the lice who feed on them,” which suppose a whole idea of the relation between the population of a novel and a social population (or the people in a political sense), and which posit a literary “equality” on a level that is no longer the one used to debate political equality. In its own way, literature too introduces a dissensus and a miscounting which are not those of political action. I am interested in the relation between the two, rather than, say, the various forms of “bias” in the representation of social categories in Flaubert. I began to reflect on these things via the question of writing history, and this reflection grew into the work on the politics of literature. Then, on account of my work on history and the writing of history, I happened to be asked by people in the arts to apply my analyses to their fields and problems – both in cinema, in which I’ve always had a personal interest (my first substantial text on cinema, for example, dealt with the relation between the “aesthetic” and the “social” in Rossellini’s Europe 51), and in other, less familiar fields (I was asked to speak, for example, “in my own way” about history for the exhibition Face à l’histoire organised by the Centre Pompidou in 1997). This last invitation gave me the opportunity to work on the question of contemporary art, a topic that had not interested me up to then. So there is a constant aesthetic core in everything I do, even if I only began to speak of literature explicitly at a particular moment, having addressed it until then through questions of history and what one might call the forms of workers’ literary appropriations. Then came requests for me to speak on topics about which I had no real competence. After what I had done, people thought I should have things to say about contemporary art, for example. I didn’t know a lot about it, but I wanted to respond to the challenge, because it was a chance to learn something new, and to learn how to talk about it. P.H.: Is there a conceptual parallel between the status of literature as you describe it in the wake of the Romantic revolution – on the one hand, the writing of everything, a systematic, encyclopaedic, even geological, literature in the manner of Cuvier and Balzac, and, on the other hand, a literature of nothing, a writing which ultimately refers only to itself – and the status of politics? As if they were both efforts to connect everything and nothing, exclusion and the universal? J.R.: There is no direct link between the two, but they both refer back to the same kernel of meaning. It is the ancient fictional or dramatic “plot,” the same organic, Aristotelian idea of the work that bursts either from a profusion of things and signs or from the rarefaction of events and senses. Broadly, literature as a regime of writing defines itself in the period after the Revolution not simply as another way of writing, another way of conceiving of the art of writing, but also as a whole mode of interpreting society and the place of speech in it. Literature defines itself around an idea of speech that somehow exceeds the simple figure of the speaker. It defines itself around the idea that there is speech [ parole] everywhere, and that what speaks in a poem is not necessarily what any speaking intention has put into it. This is all the legacy of Vico. Either that or there is language [langage] everywhere, which is Balzac’s position. There is something like a vast poem everywhere, which is the poem that society itself writes by both uttering and hiding itself in a multitude of signs. Or, if you take the Flaubertian perspective, the “book about nothing” comes to replace the lost totality. In fact, this is still Schiller’s idea of “naive” (as opposed to “sentimental”) poetry as the poem of a world (an idea with colossal force whose effects are still with us), an unconscious or “involuntary” poem for which we must produce an equivalent in the inverse form of a work that relates only to itself. The lost totality rediscovers itself on the side of nothing, but we must look at what this nothing means. Flaubert invents a sort of atomic micrology which is supposed to pulverise the democratic population. At the same time, he contributes to what we could call an aesthetic of equal intensities – opposed to the hierarchies of the representative tradition – which is the aesthetic he addresses to Madame Bovary even as he condemns her. There is a conflictual complicity between the fictional population and the social world that this literature addresses. Flaubert writes “against” Madame Bovary and the “democratic” confusion of art and life, but, at the same time, he writes from the “democratic” point of view which affirms the equality of subjects and intensities. It is this tension that interests me. Literature invents itself as another way of talking about the things politicians talk about. P.H.: For some time now, most aesthetic thinkers have emphasised the importance of modernism and the avant-garde. Among your contemporaries, you are one of the few to pay more attention to Romanticism and to the nineteenth century more generally. For you, the answers to many of the questions that aesthetics asks are still to be found in Schiller, Kant, and Balzac. What is the key to what you call the “aesthetic revolution”? 4 And how do you understand modernism? J.R.: What is the kernel of the aesthetic revolution? First of all, negatively, it means the ruin of any art defined as a set of systematisable practices with clear rules. It means the ruin of any art where art’s dignity is defined by the dignity of its subjects – in the end, the ruin of the whole hierarchical conception of art which places tragedy above comedy and history painting above genre painting, etc. To begin with, then, the aesthetic revolution is the idea that everything is material for art, so that art is no longer governed by its subject, by what it speaks of: art can show and speak of everything in the same manner. In this sense, the aesthetic revolution is an extension to infinity of the realm of language, of poetry. It is the affirmation that poems are everywhere, that paintings are everywhere. So, it is also the development of a whole series of forms of perception which allow us to see the beautiful everywhere. This implies a great anonymisation of the beautiful (Mallarmé’s “ordinary” splendour). I think this is the real kernel: the idea of equality and anonymity. At this point, the ideal of art becomes the conjunction of artistic will and the beauty or poeticity that is in some sense immanent in everything, or that can be uncovered everywhere. That is what you find all through the fiction of the nineteenth century, but it’s at work in the poetry too. For example, it’s what Benjamin isolated in Baudelaire, but it’s something much broader than that too. It implies a sort of exploding of genre and, in particular, that great mixing of literature and painting which dominates both literature and painting in the nineteenth century. It is this blending of literature and painting, pure and applied art, art for art’s sake and art within life, which will later be opposed by the whole modernist doxa that asserts the growing autonomy of the various arts. The entire modernist ideology is constructed on the completely simplistic image of a great anti-representational rupture: at a certain moment, supposedly, nobody represents any more, nobody copies models, art applies its own efforts to its own materials, and in the process each form of art becomes autonomous. Obviously all this falls apart in the 1960s and 1970s, in what some will see as the betrayal of modernism. I think, though, that modernism is an ideology of art elaborated completely retrospectively. “Modernists” are always trying to think Mallarmé and the pure poem, abstract painting, pure painting, or Schoenberg and a music that would no longer be expressive, etc. But if you look at how this came about, you realise that all the so-called movements to define a pure art were in fact completely mixed up with all sorts of other preoccupations – architectural, social, religious, political, and so on. The whole paradox of an aesthetic regime of art is that art defines itself by its very identity with non-art. You cannot understand people like Malevich, Mondrian or Schoenberg if you don’t remember that their “pure” art is inscribed in the midst of questions regarding synaesthesia, the construction of an individual or collective setting for life, utopias of community, new forms of spirituality, etc. The modernist doxa is constructed exactly at the point when the slightly confused mixture of political and artistic rationalities begins to come apart. Remarkably, modernism – that is, the conception of modern art as the art of autonomy – was largely invented by Marxists. Why? Because it was a case of proving that, even if the social revolution had been confiscated, in art the purity of a rupture had been maintained, and with it the promise of emancipation. I’m racing through all this, but I do think that this is what lies behind Adorno or Greenberg: a way of defining art’s radicality by the radicality of its separation, that is, a way of separating art radically from politics in order to preserve its political potential. Afterwards, this complicated dialectic is effaced in the simplistic dogma of modern art as the art of autonomy. Obviously, this dogma does not survive for very long in the face of the reality of artistic practices, and when it collapses, people start saying “Modernity is falling apart.” But it hasn’t: what has fallen apart is just a very partial and belated interpretation of what I call the aesthetic mode of art. P.H.: For you, then, is it a matter of maintaining the contradictory relations of the aesthetic regime, of continuing in the difficult dialectic of whole and nothing, of the controlled inscription of a generalised speech (an anonymous beauty, as you put it) and the vacillation of an ultimately silent discourse which affirms its own unconsciousness and lack of identity? You seek to continue in that tradition, rather than swing in the opposite direction, towards the postmodern, for example, or the post-whatever? J.R.: I don’t really believe in any great historical break between the modern and the postmodern. There aren’t many solid identifying features of an art that would be postmodern. How exactly are you going to define postmodernism? By the return of figuration? But that is only a part of it. By the mixing of genres? But that is much older. For me, if you want to think about breaks, it’s important first of all to understand the continuities – to understand, for example, that modern art was not born, as we still believe, in a simple and radical break with the realist tradition. The categories which allow us to think modern art were entirely elaborated in the modes of focusing perception that were first imposed by the realist novel: indifference to subject, closeups, the primacy of detail and tone. It was often novelists – like the Goncourts, for example – who as art critics reconfigured the logic of visibility in the field of painting (which was still very much figurative), valorising the pictorial material over its subject. Painting was seen in a new way, one that abstracted its subject, before painters themselves abandoned figuration. To take another example: installation is one of the central forms of contemporary art. But you will find an extraordinary passage in Zola’s Le Ventre de Paris – a completely mad book from 1874, a great hymn to poetry, and to great modern poetry in particular. Now, what is this great modern poetry? And what is the great monument of the nineteenth century? Les Halles [the central markets] in Paris. Zola installs his painter, Claude Lantier – the impressionist painter as he sees him, a painter in search of modern beauty – in this monument of modernity. At one point, Lantier explains that his most beautiful work wasn’t a painting. Rather, he created his masterpiece the day he redid his cousin the butcher’s window display. He describes this display, how he arranged the blood sausages, dried sausages, turkeys, and hams. Still with Zola, in Au Bonheur des dames you also have the department store as a work of modern art, with the capitalist, Octave Mouret, as the great poet of modernity, the poet of commodity installation. At that time, then, no one made installations, but an indecision between the art of the canvas and the art of display can already be marked. An art that has only developed in the last twenty or thirty years had, in some sense, already found its thought and its visibility. The “modern” solitude of art has always also been its non-solitude. P.H.: But what if you take a hard modernist like Rothko, whose last paintings revolve around blackness, the absence of all figuration, all “application”? J.R.: Sure, but that was an idea of modernism, and, in any case, we know that it wasn’t an idea of pure painting, since at the time Rothko was becoming more and more mystical. Of course, you can cite painters who fit into the exemplary configuration of modernism as it was constructed, most notably, by Greenberg. But, in the end, what is this configuration? A short sequence of abstract art done at a particular moment by artists with roots in other traditions, notably surrealism. You absolutely cannot reduce modern art to this short sequence of abstract painting. Modern art is also constructivism, surrealism, Dadaism, or what have you – all forms of art with roots in Romantic thinking about the relation between art and life. I do not like modernism as a concept, because it seeks to identify an entire regime of art with a few particular manifestations that it presents as exemplary, interprets in an extraordinarily restrictive way, and links to an absolutely uncritical idea of historical time. P.H.: Moving on now to my last questions, which are mostly about the immediate intellectual context of your work. I was struck by your reading of Freud, or rather your literary recontextualising of Freud’s work in L’Inconscient esthétique [2001]. Can you generalise your position a little, to incorporate Lacan, for example – Lacan as a thinker who insists on the primacy of speech, precisely, on the equality and essential anonymity of all speech phenomena, on the importance of listening to speech qua speech, etc.? J.R.: I won’t say very much about Lacan, because I still really don’t know what to think of him or, rather, what to do with his thought. For me, the problem with Lacan is that he seemed to hover between several rationalities. When my generation got to know him, it was the time of the primacy of the signifier, the great structuralist moment, which in my view had no important consequences at the level of aesthetics. What became visible in Lacan’s subsequent work, though, was a whole other legacy, the surrealist legacy of Bataille and all those movements in the 1930s which wanted in their own way to rethink relations between aesthetics and politics – a whole way of thinking the obscure rationality of thought that was not dependent on the Freudian logic of the symptom (itself still linked to an Aristotelian poetics of history as causal agency). Lacan, in this sense, is a lot closer to Romantic poetics than Freud is. Where Freud deciphers, Lacan turns to the silent words that remain silent, those ultimate blocks of nonsense which can either become emblems of an absolute freedom (à la Breton) or embody the accursed share, the opaque residue impenetrable to sense (à la Bataille). For me, that is ultimately the difference Lacan brings. This difference shows up clearly in the uses Freud and Lacan make of Sophocles. Freud obviously constructs everything around the figure of Oedipus, around the link between incestuous desire as an object and an Enlightenment notion of rationality (the path of interpretation reconstituting the causal chain). Lacan, on the other hand, turns more and more to Antigone, whose desire does not lend itself to interpretation, who wants only to maintain a stubborn fidelity to the powers below, who, in short, wants only death. I’m thinking here of Lacan taking up Antigone at the time of the Baader-Meinhof gang, to show that she has nothing to do with the icon of “human rights in the face of power” that she is always made out to be, but is in fact closer to Ulrike Meinhof and the radicality of those German terrorists. The regime of signification in which Lacan constructs Antigone is a lot closer to what one might call aesthetic reason than the one Freud uses. The latter reconstitutes classical causalities, where Antigone as Lacan reconstructs her is closer to those half-obscure figures of the Romantic and realist periods. P.H.: Is there a risk that your idea of silent speech might lead eventually to silence pure and simple? Were you ever tempted by the mystical tendency that runs through the work of Bataille, precisely, and to some extent in the writings of Blanchot, Foucault and Deleuze, for example? J.R.: I’ve never been very receptive to either Blanchot and Bataille or to what the following generation – Foucault, Derrida, Deleuze – made of them. It all struck me as very opaque. Rather, I became sensitive to the question through the whole problematic of the will in the nineteenth century. In nineteenth-century literature, let’s say from Balzac to Zola – not forgetting Strindberg, Ibsen, and what happens in Dostoyevsky and Tolstoy – there is a long train of thought that either challenges the will or carries it on to some final disaster. Thinking through the death drive begins not just with stories of the will exacerbated (as with Vautrin) or annihilated (as with Oblomov) but also with the very logic of the regime of writing proper to literature, its way of untying the representative knot connecting action, will, and meaning. At the heart of the aesthetic regime of art there is an idea that the highest effort of the will is to identify itself with the highest point of its abdication. So, there is something like a race towards nothingness, which is always represented either as the hero’s experience or identified as the force which runs through writing itself. I have found the theme of the self-destructive will, which is generally thought to belong to Schopenhauer and nihilism in the strict sense, throughout the literature of the nineteenth century. And I have been rereading Freud’s texts in this light, telling myself that it is really this he is measuring himself against. I myself have no inclination towards a mysticism of silence, but I do feel very deeply the link between a whole regime of writing and the desertion of a certain idea of meaning, between the privilege of “silent speech” and the dramaturgy of a self-annihilating will. P.H.: Your own writing is often heavily ironic, motivated by a sort of dynamic indignation, as if the weight of history and silence has forced you into a constant movement. Is this part of your resistance to that nihilism? J.R.: I’d say that, broadly speaking, it is less a specific resistance to the death drive than part of a strategy of writing which tries to put uncertainty back into statements. On the one hand, it’s a matter of introducing some give or play into dogmatic statements. On the other, you can only contest the assurance of people with knowledge by undoing the way they construct their other: the one who does not know, the ignorant or naive one. That is why I wanted to give the discourse of workers’ emancipation its share of play, of doubt about what it says. I wanted to shatter the image of the naive believer in a land of milk and honey, to show that workers’ utopian discourse always also knows at a certain point that it is an illusory and ironic discourse, which does not entirely believe what it says. The problem is to challenge the distribution of roles. And that concerns the status of my own assertions as well. I have tried to offer them as probable assertions, to avoid a certain affirmative, categorical style which I know is elsewhere encouraged in philosophy, but which I have never been able to assimilate. P.H.: How do you situate yourself in terms of your contemporaries? Your interest in writing and the deferral of certainties seems to align you, up to a point, with Derrida; on the other hand, your interest in axiomatic equality and exceptional configurations of universality reminds me of Badiou. But it’s hard to imagine two more different conceptions of thought! J.R.: Those are not quite the markers by which I would define myself. I have read Derrida with interest but from a certain distance, from a slightly out-of-kilter perspective. (If I too, in my own way, have tried to reread the Phaedrus, it has been in order to find at work in that text not the pharmakon or dissemination but a sharing out of the modes of speech homologous to the sharing out of the destinies of souls and bodies – in short, a politics of writing.) If, among the thinkers of my generation, there was one I was quite close to at one point, it was Foucault. Something of Foucault’s archaeological project – the will to think the conditions of possibility of such and such a form of statement or such and such an object’s constitution – has stuck with me. As to Badiou, there are doubtless certain similarities: a shared fidelity to a common history, a similar way of thinking politics by separating it from state practice, the question of power, and the tradition of political philosophy. But there is also in Badiou this affirmative posture oriented towards eternity which I absolutely cannot identify with. His idea of absolute disconnection or unrelation, his idea of an event that stands out sharply against the situation, his idea of the quasi-miraculous force of the evental statement – these are ideas I absolutely cannot share. P.H.: To close, what are you working on now? What are your plans for the future? J.R.: I have no great project. I’m still working on questions around the aesthetic regime of art, the relation between aesthetics and politics, what you could call the politics of literature. I’ve now accumulated masses of material on the topic which I don’t quite know what to do with. I have enough material for a five-volume summa on the aesthetic regime of art, but no desire to write it. So I am trying to find forms of writing that allow me to make a few points about what is at stake in thinking the aesthetic regime of art – forms that, through significant objects and angles, allow me to say as much as possible in as little space as possible. I suppose my idea of research is indissociable from the invention of a way of writing. Peter Hallward French Department King’s College London The Strand London WC2R 2LS UK Jacques Rancière c/o Éditions Galilée 9, rue Linné 75005 Paris France ANGELAKI journal of the theoretical humanities volume 8 number 2 august 2003

0 Comments