|

by Yvette Granata AKA, THE BIT TORRENT OF EARTHThis text is a non-script that accompanies the film Superficie des Continents. While the film explores archival footage of the surface of the earth, this text traces the archive of the surface of the earth in another way. It is a textual montage or network of different surface areas. It is meant to be read as a separate fragment. Des Continents: 1. SUPERFICIE 2. CONTINENTS 3. CONTINENTS 4. MICROORGANISM 5. ORGANISM 6. EARTH 7. ORGANISM 8. FACTORY 9. EARTH 10. CONTINENT 11. ANOTHER EARTH 12. MICROORGANISM 13. THE END This is the Area of the Continents. This is not a map! Only nature can repeat itself. Nature never apologizes – Vladimir Dmitrov Ecology of Immortality (2007) Clouds are not spheres, mountains are not cones, and lightning does not travel in a straight line. The complexity of nature's shapes differs in kind, not merely degree, from that of the shapes of ordinary geometry, the geometry of fractal shapes. – Benoit Mandelbrot, The Fractal Geometry of Nature (1983) 1 1. SUPERFICIE2For smooth surfaces, there is a unique natural notion of surface area. If a surface is very irregular or rough, however, it may be impossible to assign an area to it at all. A typical example is given by a surface with spikes spread throughout in a dense fashion. The mathematical definition of surface area in the presence of curved surfaces is considerably involved. The surface area is not the sum of an object’s faces. The surface area of a solid object is the total area of the object's faces and its curved surfaces.3 There are crevices and turns and parts of curves and other things to be measured. It is difficult to measure the surface of curves. They contain their own special face, and there are folds within the special faces. Therefore: we cannot ever be sure how many faces an object has. Many surfaces of this complicated type occur in the study of fractals. A fractal is a mathematical set that typically displays self-similar patterns, which means the patterns are the same from near as from far. The surface of the earth is a good example of an irregular surface that exhibits fractal patterns. Sometimes you must look from a far distance and other times from a very close one. In order to do this, you must change in size. If you cannot see the sameness of things, it may be because it is not something you can see at all. The Earth’s surface may seemed fixed, but underneath our feet there is a constant motion that we cannot notice until there is an earthquake or a volcanic eruption. There is molten rock. Sometimes it becomes lava. 2. CONTINENTSBeneath the surface of the Earth, the molten rock moves. Heraclitis, the pre-socratic philosopher, lived between 535 - 475 BCE in Greece. He is known for coining the phrase “Panta Rhei” or “Everything must flow.” He also said that you cannot step in the same river twice. And also that you cannot step in the same volcano twice. 3. CONTINENTS4Panta Rei is an Italian Restaurant in North Beach, San Francisco. Here are some reviews: “It is worth the walk.” “Whenever my husband and I visit San Fran, we always make it a point to have either lunch or dinner at Panta Rei. It is by far the best Italian place in San Fran to eat and the atmosphere is very welcoming and fun. We have always ordered something different with every visit and have always had an excellent meal every time. Good Italian food is hard to find here in Phoenix, so I make my own which we like best; however, I say give Panta Rei a try.” “I think I ordered the wrong thing. Squid ink pasta. I wouldn't recommend this. The noodles were dry and the seafood was tough. In hindsight I should have sent it back. I also felt sick later that night.” 4. MICROORGANISM5Microorganisms can cause people to become sick after eating at restaurants that have served food that contain certain microorganisms. Normally, this is an accident. Perhaps that is what Voltaire meant when he said, “the definition of monsters is more difficult than is generally imagined.” The surface area of the micro-world is also more difficult to describe than is generally imagined. The inner membrane of a mitochondrion has a large surface area due to infoldings, allowing higher rates of cellular respiration. The surface area to volume ratio of a cell imposes upper limits on size, as the volume increases much faster than does the surface area, thus limiting the rate at which substances diffuse from the interior across the cell membrane to interstitial spaces or to other cells. Indeed, representing a cell as an idealized sphere of radius r, the volume and surface area are, respectively, V = 4/3 π r3; SA = 4 π r2. The resulting surface area to volume ratio is therefore 3/r. Thus, if a cell has a radius of 1 µm, the SA:V ratio is 3; whereas if the radius of the cell is instead 10 µm, then the SA:V ratio becomes 0.3. With a cell radius of 100, SA:V ratio is 0.03. Thus, the surface area of a cell falls off steeply with increasing volume. In other words, the more a cell contains, the less surface it has 5. ORGANISMThe poet said, “Silent is the life of flowers.” At the University of Western Australia, plant physiologist Monica Gagliano says, "We have identified that plants respond to sound and they make their own sounds," and added that, "The obvious purpose of sound might be for communicating with others."6 6. EARTHThe Earth is not a sphere. It is an oblate spheroid. 7 That means that all of the globes I have ever seen are wrong. Even though the tallest mountain above sea level on Earth is Mount Everest, the feature that is furthest from the center of the Earth is actually Mount Chimborazo in Ecuador. It is also the point on earth that is closest to the Moon.8 If the Earth were a sphere, the top of Mount Everest would be the farthest point from the center of the Earth. But it’s an oblate spheroid, not a sphere, and so it’s Chimborazo, not Everest. Not knowing that Chimborazo is the point on Earth that reaches farthest into space is also what is meant when the poet said, ‘Silent is the life of flowers. 7. ORGANISMThe surface area of an organism is important in several considerations, such as regulation of body temperature and digestion. Animals use their teeth to grind food down into smaller particles, increasing the surface area available for digestion. The epithelial tissue lining the digestive tract contains microvilli, greatly increasing the area available for absorption. Elephants have large ears, allowing them to regulate their own body temperature. In other instances, animals need to minimize surface area; for example, people will fold their arms over their chest when they are cold to minimize heat loss. 8. FACTORYSomeone once said to the writer that the truth can be found in a concrete tank. The factory workers searched and dug holes and made machines that could dig more holes. They made the dirt into concrete and poured the concrete to build a room, the concrete tank. Some people started to say that half of the universe was the result of a giant reflection of itself in a cosmic mirror. The workers found a broken shaving mirror underneath the dirt, where someone had forgotten it. “How did it get there in the first place?” They wondered as they sat in the tank, “Could this be the other half of the universe?” 9. EARTHEarth is the densest planet in the Solar System. When microscopic plants in the ocean die, they fall to the bottom of the ocean. Over long periods of time, the remnants of this life, rich in carbon, are carried back into the interior of the Earth and recycled. This pulls carbon out of the atmosphere, which makes sure we don’t get a runaway greenhouse effect. That’s what happened to Venus. So far, ours is the only planet that we have confirmed to have life. After Enrico Fermi won the Nobel Prize in physics, he asked the famous question, “Our galaxy should be teeming with civilizations, but where is everybody?” If we are the only planet with life, then Earth is a Single Point Of Data. Albeit Recycled Data. If we are a single point of data, then the Earth is a very heavy-hearted island. Or a floating washing machine. 10. CONTINENTSIn Italy, Umberto Eco wrote a novel in 1988, called Foucault’s Pendulum. In the novel, there is a secret society called ‘Panta Rhei.’ The novel is about an invented conspiracy. The pendulum is not of or related to Michel Foucault. Foucault’s pendulum demonstrates the rotation of the Earth. It also allows you to see the surface of the Earth move underneath a pendulum. I saw this demonstrated once with a pendulum and a series of empty coca cola bottles. 11. ANOTHER EARTHEarth is lonely. It is surrounded by other planets without life. It wants to find others like it. People on earth have started to look for life on other planets and other worlds. People question whether or not they are alone on Earth, if Earth is alone in the universe. They say when there is one cockroach, there are a hundred more. What if another civilization of cockroaches had telescopes? In December 1990, when the Galileo spacecraft flew by Earth in its circuitous journey to Jupiter, scientists pointed some of the instruments at Earth to see how the planet looked from space. Since we knew life could be found on Earth, this exercise helped create some criteria that if found elsewhere, would point to the existence of life there as well. One of the most telling of the criteria for finding life that was discovered by the Galileo flyby was what is called the vegetation red edge: a sharp increase in the reflectance of light at a wavelength of around 700 nanometers. This is the result of chlorophyll of plants absorbing visible light but reflecting near infrared light strongly.9 If aliens look to Earth right now, they would see a red tinge covering the people looking back out to the skies for them. To aliens, the surface of the human face looks red. 12. MICROORGANISMIn The Life and Death of Planet Earth by Peter Ward and Donald Brownlee, the authors chronicle how the Sun’s energy output is slowly increasing. They say in as soon as 500 million years, temperatures on Earth will rise to the point that will make most of the world turn into a desert. And then this will happen: 1. The largest creatures won’t be able to survive anywhere but on the relatively cooler poles. 2. Because of this, over the course of the next few billion years, evolution will seem to go in reverse. 3. The largest organisms and least heat tolerant animals will die out, leaving insects and bacteria. 4. Finally, it’ll be so hot on the surface of the Earth that the oceans will boil away. 5. There’ll be no place to hide from the terrible temperatures. 6. Only the organisms that live deep underground will survive, as they have already for billions of years. 13. THE ENDNotes 1 Mandelbrot, Benoît B. (1983). The fractal geometry of nature. Macmillan. 2 Gouyet, Jean-François (1996). Physics and fractal structures. Paris/New York: Masson Springer. 3 See definition of surface area: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Surface_area 4 http://www.yelp.com/biz/panta-rei-restaurant-san-francisco 5 For a description of microorganisms and surface area see: Microbial Ecology: Organisms, Habitats, Activities by Heinz Stolp, 1988, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press 6 For more info on how plants talk, see: http://www.livescience.com/27802-plants-treestalk-with-sound.html 7 http://www.universetoday.com/25756/surface-area-of-the-earth/ 8 For a description of Mount Chimborazo, see http://www.mountainprofessor.com/highest-mountains.html 9 http://www.universetoday.com/23560/viewing-earth-as-an-extra-solar-planet/ This text was created as part of the joint artistic research project, Fragmentation and Feedback Loops, with the University of Amsterdam & Hogeschool voor de Kunsten Utrecht (HKU). Fragmentation and Feedback Loops was exhibited at the Eye Film Museum in Amsterdam in January 2014. Yvette Granata: Phd media study/theory/practice SUNY Buffalo. Non-philosophy, media art, tech, ultra-terrestrials

0 Comments

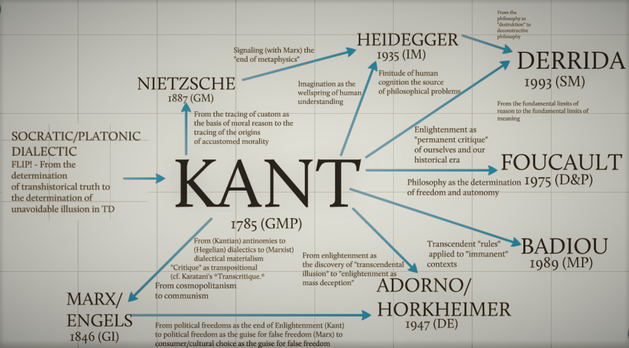

(Edited version of paper presented at the Deleuze Studies Conference in Rome, July 2016.) 1.1 From ‘What is Philosophy’ to ‘Where is Non-Philosophy’?While Deleuze and Guattari’s What Is Philosophy? begins and explores the question of its title, charting the planes and operations of philosophy, science and art, the last chapter of the book might be read as shifting towards another question. In bringing up ‘nonphilosophy’ near the book’s end, Deleuze and Guattari ask, it seems, not what but where is a non-philosophy? Here they speak of the non-localizable interference between the disciplines and their corresponding ‘non’, saying that: “Finally, there are interferences that cannot be localized. This is because each distinct discipline is, in its own way, in relation with a negative” and that “the plane of philosophy is prephilosophical insofar as we consider it in itself independently of the concepts that come to occupy it, but non-philosophy is found where the plane confronts chaos.” (WP, 218, my italics). Deleuze and Guattari’s pre-philosophical plane here does not consist of the historical concepts of philosophy, but is a plane not yet inhabited by philosophical concepts. They therefore make the distinction that a pre-philosophical plane is not a non-philosophical plane. A non-philosophy is still somewhere else. It is not on the planes of science or art; it is not in chaos either. Instead, they situate non-philosophy in a non-localizable place. While not localizable to a plane, it is also not completely ‘non-localizable’ either. As they point out, non-philosophy is located where the plane confronts chaos and so is located on the edge of philosophy, dangling off in an interstitial space (a space but not a plane) between philosophy’s plane and chaos. Here is where they then put the footnote about François Laruelle as being engaged in one of the most interesting projects of contemporary philosophy, his project of non-philosophy. Laruelle’s non-philosophy, however, is in spatial disagreement with Deleuze and Guattari’s map at the outset. The non-philosophy of Laruelle is not located in a space between the edge of philosophy and chaos. While initially, this cartographic disagreement is useful for a comparison of their non-philosophies, this paper looks further to how Laruelle not only redraws the map of philosophy/non-philosophy, but also to where he performs inverse operations to Deleuze’s philosophy of difference. I look not only where Laruelle departs from Deleuze, but where he connects and then engulfs, deforms, and debases Deleuze’s difference. In order to do so, this paper explores a few aspects of Laruelle’s non-philosophy and his concept of the gnostic matrix as an inverse operation and sublimation of Deleuze’s difference-itself. Ultimately, I think through the re-shaping of difference itself into a repetition of gnostic matrices. 1.2 Not ‘Where is Non-Philosophy,’ but ‘Where is Philosophical Interference?’Laruelle not only draws a different map than Deleuze and Guattari’s non-philosophy but also erases the outline around the plane of immanence; he does not so much ‘deterritorialize’ Deleuze and Guattari’s version of immanence as outright reject it. One of the main tenets of Laruelle’s thought is a critique of philosophy’s claim to be able to philosophize immanence, calling “this bewitched belief, which philosophy has known quite well . . . the Principle of Sufficient Philosophy (PSP)” (‘Non-Philosophy’, 98). Within Laruelle’s critique of the system of sufficient philosophy, immanence has been proclaimed by philosophers in which they “distinguish between themselves by a system of diversely measured mixtures of immanence and transcendence, by these infinitely varied twists and interlacings” (‘Principles’, 17). This mixology, or in Laruelle’s term amphibology, is the manner in which philosophers are always self-assigning their authority to describe the real, and merely creating an ad hoc combination of immanence and transcendence as exercises of performative authority. Laruelle therefore neither agrees with Deleuze and Guattari on what the nature of philosophical ‘interference’ is or what it entails. Where for the latter, there is an interference pattern between the plane of philosophy and chaos, and an interference between the planes of the disciplines of art and science, for Laruelle the amphibology of a sufficient philosophy is already the philosophical interference. Philosophy itself has an interior interference pattern produced by its decisionism; it is the finitude of philosophy’s own decision that interferes with philosophy as a part of its planar design (a design bolstered by Deleuze). In this way, we need not draw an outline around the plane of immanence that separates it from an outside chaos. Amphibology is chaos. In a letter from 1988, Laruelle tells Deleuze, “By chaos, chora, or (non-)One, I describe an absolutely infinite and indivisible receptacle, containing an infinity of philosophical decisions”(‘Decision,’ 396). As such, Laruelle moves Deleuze’s chaos from its outside place and shapes it instead into the infinite garbage can containing philosophy’s decisions. Laruelle draws a philosophy receptacle that is already filled up with chaos. Nevertheless, Laruelle’s non-philosophy is in a similar phase-state as Deleuze and Guattari’s in terms of its initial appearance, as both admit to be born out of a recognition of the condition of a philosophical interference. Whether from outside or from within, non-philosophy seemingly begins with the recognition of an interference. This condition is hinted at already in Deleuze and Guattari’s statement: “They [science, art, philosophy] do not need the No as beginning, or as the end in which they would be called upon to disappear by being realized, but at every moment of their becoming” (WP, 218). They thus point out that the ‘no’ of a philosophy would be at every point of the becoming of a non-philosophy, and not at a crossing of a threshold or at an edge. The No is neither the end of philosophy because of a realization of philosophy, but is a constant and corollary no — the becoming of a non. Indeed, they are here moving towards Laruelle. In Laruelle’s letter to Deleuze however, he further unhinges the state of non-philosophy, stating: “a thing, a philosophy, will be called free when it exists as cause of itself … when it is at once determinate and determinant itself. On the contrary, a thing will be called constrained when it is determined by another to exist and to operate”(‘Decision’, 397). A ‘No’ is a constrain. A non, however, is a free radical. In this way, Laruelle also gets rid of their ‘No,’ His distinction of ‘constrain’ versus ‘free,’ directly addressed to Deleuze, allows instead for a non-philosophy which is not relational to a position to philosophy, is not between a philosophical plane and the chaos outside, and is now neither a ‘no’ in relation to ‘a philosophy.’ It is determinant from its own structure and instead uses philosophy as a material. We might then better compare Laruelle as making another Deleuzian-Guattarian ‘pre-philosophical plane’ rather than a version of their non-philosophy, but without the outlines of a plane. There is a constrain without constraint of another, or is self-constraint, in a non-positional space. The determination of non-philosophy is more radical, akin to a free radical or a doppelgänger to philosophy. Put another way, Laruelle’s non-philosophy is face to face with philosophy, not hierarchically above philosophy, not dangling at its edge, nor taking it from behind.1 Non-philosophy approaches philosophy from multiple angles, collides into it, re-mixes it, eats it. Looking further at an example of Laruelle’s non-philosophy as a doppelgänger in the act, I look to Laruelle’s repetition of a gnostic matrix as facing Deleuze’s system of difference and how Laruelle ultimately sublimates Deleuze’s repetition of difference. 2.1: Insubordinate Difference as Difference In-itself | DeleuzeIn Difference and Repetition, Deleuze argues against the concept of difference as a destructive and ‘evil’ force as it appears throughout philosophy, asking, “it is obviously difficult to know whether the problem is well posed in this way: is difference really an evil in itself? Must the question have been posed in these moral terms? Must difference have been ‚mediated‘ in order to render it both livable and thinkable?” (DR, 30). Deleuze moves from the concept of difference as ‘evil mediation’ to the concept of difference-itself as a productive force, as a thing itself that shapes things. He thus begins with an effort to liberate difference from its status as a subordinate operation of ‘difference from.’ The problem of ‘difference from’ is that it necessarily frames difference as a negative operation by which things are compared to a transcendental sameness, or is an operation in which representation is what mediates from an original (the copy versus the original), and in which the mediated differs from a transcendental original by degrees of destruction. For example, Deleuze gives Plato’s distinction between the original and the image, the model and the copy, where “the model is supposed to enjoy an originary superior identity (theIdea alone is nothing other than what it is: only Courage is courageous, Piety pious), whereas the copy is judged in terms of a derived internal resemblance” (127). Deleuze, however points out that it is not only the copy that is subordinated to the Idea, but that difference itself as a concept must come second to comparing two similar things, “[i]ndeed, it is in this sense that differencecomes only in third place, behind identity and resemblance, and can be understood only in termsof these prior notions” (127). Getting away from the Idea and difference as a comparison to itssameness, Deleuze constructs a system based on the primacy of difference, or difference itself,that henceforth prevents a system of comparisons of sameness orsimilarity. Difference itselfbecomes neither the description of a relation nor the comparison of the Idea and its mediated forms, but is the condition under which all things are subjected or through which they are produced. Liberating difference from its secondary nature of the Idea, Deleuze constructs asystem of differentiation and differenciation, a dynamic system that follows from difference itself. Difference is therefore no longer a secondary term that denotes comparison, but becomes the inherent function of the system. As Deleuze describes: Difference is not diversity. Diversity is given, but difference is that by which the given is given, that by which the given is given as diverse. Difference is not phenomenon but the noumenon closest to the phenomenon. It is therefore true that God makes the world by calculating, but his calculations never work out exactly [juste], and this inexactitude or injustice is the result, thisirreducible inequality, forms the condition of the world. The world ‚happens‘ while God calculates; if the calculation were exact, there would be no world. The world can be regarded as a ‚remainder‘, and the real in the world understood in terms of fractional or even incommensurable numbers. Every phenomenon refers to an inequality by which it is conditioned (241). Difference as a noumenon of the phenomenon is an internal function of the phenomena by which all things are the result of that functional kernel. What makes difference perform its function and produce what is in the world via its inequality? It is God tied to a calculator that endlessly unevenly calculates, and it is the calculator that performs the function of difference-itself. Deleuze therefore makes it so difference is not repetition of variations of a transcendental same— because only that which differs via difference is what constitutes what is in the world.Difference-itself is the primary function that repeats, and the world is the garbage can for thejetsam of God’s calculator. 2.2 The Debasement of Sameness | LaruelleDeleuze’s gesture of thinking through difference is intimately connected to the gesture torethink the Idea, or to take it from behind. While on the one hand, the problem of representation of the Idea is framed as a mediation (the evilness of a difference negatively framed), Deleuze also describes that the ‘innate good’ of the Idea is also still a problem on the other side of thecalculator. He says: “The very conception of a natural light is inseparable from a certain valuesupposedly attached to the Idea – namely, ‚clarity and distinctness‘; and from a certain supposedorigin – namely, ‚innateness‘. Innateness, however, only represents the good nature of thoughtfrom the point of view of a Christian theology”(146). Deleuze, then speaks of the restitution of the Idea via not only difference on the one side, but also the explosion of the Idea with a Dionysian value. The priority of a difference-itself and the Dionysian destruction of the innategood are both parts of a two-pronged way to solve the problems of the innate ‘clarity and distinctness’ of the Idea and the evil of a negative difference. For Francois Laruelle, however, we do not need to destroy the Idea with Dionysian value nor make difference a primary function — something else can be done. In his text, Christo- Fiction: The Ruins of Athens and Jerusalem, Laruelle seemingly gives an answer to Deleuze’s remark above on the concept of ‘clarity and distinctness’ as inseparable from innateness. While Laruelle similarly aims to remove the innate so-called goodness of Christian theology tied to theIdea, he instead speaks of “a gnostic-type knowledge” in which “it is possible to clarify a secret in a quantum-theoretical manner without absolutely destroying it”(‘Christo’, 5). For Laruelle, we do not have to destroy, or rectify the Idea with Dionysian value in order to clarify a secret. Laruelle switches thus from innate clarity of good knowledge, the Idea, to the ‘secret,’ and gives a method that is neither difference itself nor destruction, but a quantum theoretical limit point.Laruelle reminds us of the Heisenberg principle — that “it is a known principle that, in quantum theoreticalterms, to clarify a supposedly given or existent secret is automatically to undetermine it in and through this very knowledge” (5). In other words, Laruelle aims to generalize “the quantum ‘law’ of that phenomenon” in order to draw out an uncertainty principle of any ‘given secret’ — a principle of under-determinancy that is no longer only for quantum physics butclaimed as a non-philosophical principle. Instead, ‘the quantum manner’ is made into a conceptual principle of the necessary preservation of the unknownability of two states at once — a concept of simultaneity that functionally undermines both the innate stability or clarity of the Idea and also Deleuze’s difference-itself. Laruelle henceforth, I argue, plays out the non-philosophical doppelgänger to Deleuze’s difference itself, and thinks through its inverse. Instead of the rectification of difference from its negative and evil mediation role, it is a debasement of the sameness of the innate that Laruelle puts forth. This takes the supposed good value, clarity and distinction away from innateness at the outset, not by constructing a difference-itself, but with the quantum as a non-theological innateness of uncertainty. As Laruelle states, “[w]ith new means, of nontheological provenance and of what we shall call a ‘quantum-oriented’ order, we have won the right to be atheist religious leaders—that is to say, atheists capable of taking religions from the side where they are usable, and of relating them to that special ‘subject’ called ‘last instance’” (CF, x). Similar to his description of the principle of sufficient philosophy, Laruelle frames theology in the same manner, naming a Principle of Sufficient Theology (PST). More so than a theological work, his text implements the method of non-philosophy in the context of theology and the context of theodicy. It is a non-philosophical free-radical facing both philosophy and theology, taking them from the side at the same time. As Laruelle emphasizes, the text “is not written so as to enrich the treasury of theological knowledge” and that “our problem is not that of traditional theology and christology. . . they are first-degree disciplines or symptomal material, like the philosophy with which they are impregnated” (vi). Laruelle makes clear that he is taking direct nonphilosophical aim at the philosophical decision of the innateness of the Idea with theology as his material. As he claims that all of philosophy contains an inner ‘christic kernel,’ the innate good clarity that Deleuze calls ‘natural light’, Laruelle goes on thus to take the concept of Christ (as Idea) and subtracts God from the equation. As such, we leave Deleuze’s God-with-a-Calculator, and go forward in an inverse reciprocal manner as Laruellian quantum atheists with christ without-god. 3.1 The Repetition of the Gnostic MatrixWhile perhaps strange to think of ‘the quantum’ and ‘Christ’ together, Laruelle does so in order to establish the mode for an atheism of christ, a non-religious and godless christic thought — in order to take aim at philosophy. He does so by using the ‘gnostic’ as a sort of uncertainty principle inserted instead of god. In this way, Laruelle uses the gnostic uncertainty principle (a ‘gnostic orientation’) as a method of “bracketing out the theological point of view as thedominant point of view”(5). Thus, where Deleuze redeems difference, or makes difference-itselfa positive or primary function in order to take out the ‘evil’ of difference while leaving the rest of philosophical decisionism intact, Laruelle resurrects the gnostic, making the christ-without-god, a positive force of heresy that preemptively leaves behind the evilness of difference. This christ without god is able to pre-empt the ‘evilness’ of difference because rather than destroy the Idea, it newly deforms it with uncertainty and debasement. The Idea itself is reformed as it is hollowed out and pulled down by Laruelle into a basement where it becomes a generic messiah dwelling in quantum uncertainty. As such, introducing the gnostic is neither destruction nor redemption of difference, but a lowering of innate good into a generic hole. Laruelle poses the gnostic and the quantum christ, I stress, in order to work in a nonphilosophical manner that aims to remain always insufficient, where ‘we have on one side a Principle of Sufficient Theology, and on the other side (the side from which our struggle is prosecuted) a necessary but nonsufficient faith’ (xii). This is where he interchanges nonphilosophy and gnostic theology in which “Christ is simply the name of the science of Christ, that its other name is gnosis, and that ‘gnostic theology’ therefore means that theology is abased (without being completely negated) as object of gnosis—nothing in these radical axioms belongs to any known Christianity” (3). The gnostic orientation and the christ-without-god replaces philosophical decision in the form of a “messianic wave” that is “a vector, and not a circle” because, as Laruelle emphasizes, “the immanence of that which does nothing but come messianically must be sought in the greatest depth of the “without-return” or of the Resurrection of Christ” (173). This is the method in which Laruelle redrafts the notion of ‘return’, refashioning it as resurrection, which is not cyclical but operates like a wave function and a vector (i.e., it moves in one direction). Such is how he puts forth ‘immanent resurrection’ as a replacement of Eternal Return. The functional behavior that Laruelle describes of this immanence is that it moves outfrom the ‘greatest depth’ of the ‘without return,’ or as a function that seems to come up from the depths of sameness (from the basement upwards). It is a ‘sameness’ function which undercuts the Deleuzian system of difference-itself that moves from virtual and actual in reciprocal entanglements, pointing out instead that “[t]he messianic wave… is not conflated with the closed-up oscillatory, with the symptoms of divine transcendence”(172), and also that “[t]he Resurrection is not a new creation… the determination of the order or the Last Instance is the Son who rises or ascends and brings down the Father . . . above all it does not form a plane of immanence like a secularized form of the plan of salvation” (210, my italics). Laruelle emphatically underdetermines the Idea and here specifically aims at Deleuze’s system of difference, transcendental empiricism, and the notion of the plane of immanence. With underdetermination, or ‘undergoing,’ the function of a wave-vector from the basement of sameness wipes out Deleuze’s God’s calculator of difference. Undergoing is functionally equivalent to Deleuze difference-itself, but by other means, via a repetition of sameness. It is a part of what Laruelle describes overall as a matrix: “If you must have a governing thesis or a principle then here it is, in all its brutality: the fusion of christology and quantum physics “under” quantum theory in its generic power, and no longer under theology. This is called a matrix” (14). A repetition of the gnostic matrix is a repetition of under-determined sameness, which repeats the same under-determinancy. The gnostic matrix and its orientation is an undoing of the decisionism of innateness and difference (of philosophy and theology at once.) To rephrase, the gnostic matrix itself produces a known uncertainty (a cognizant gnosticism) that proceeds with the repetition of sameness. It is in this way that undergoing is the inverse of difference itself: it too decouples difference from an ‘evil’ comparison to an ideal, but does so by placing both under the cognizance of its axiomatic parts and within a matrix of uncertainty. Thus a gnostic matrix empties out or discards both innate clarity and difference from the Idea. It does not claim a description of the real, but gets rid of the philosophical self-assignment that compares innate ideas and representations or differences thereof in order to move forward instead with an underdetermined state as the case: “Gnosis cuts down [the] absolute will to knowledge, and radicalizes or differentiates between knowledge and the cognizance of this knowledge”(10). As such, Laruelle reframes the problem that Deleuze sets out in the beginning: it is not difference attached to an Ideal that is the wolf at the door, but rather, it is the privation of the cognizance of knowing the decision of the Ideal which threatens. The cognizance afforded by the gnostic matrix is the manner in which we then “find some way to make intelligible its unintelligibility and its unlearned character” and “discover the means to conserve and manifest its secret without destroying it qua secret with an inadequate, rationalist light” (4). The gnostic matrix that repeats is then the form that gives us, not innate light, but an inadequate rationalist non-light. The repetition of the gnostic matrix can thereby underwrite the function of Deleuze’s difference in-itself, as its matrixial uncertainty allows us to move away from innate light altogether, making the Idea always a perpetually inadequate sameness repeating. Laruelle specifically lays out this notion, again in relation to Deleuze, stating: Negative theology and philosophy…whether affirmative or negative, they form mélanges, in the name of the All or the Absolute, of conceptual atomism and wavelike fusion, sometimes in real oscillatory machines (Deleuze). This mélange supposes the two styles to be separate and unitarily unified, whereas the quantum point of view also utilizes both of them, but without mixing or identifying them, rendering them indiscernible as superpositions.” (170) What Laruelle here critiques of Deleuze is his ‘mélange,’ or the amphibology of the mixture of absolutes and oscillations of difference, because such is not cognizant of its own decisionism.Thus it requires a move away from mélange towards matrix, which does not mix but maintains axiomatic parts. 3.2. The Sublimation of Difference: or Difference placed inside a Matrix that RepeatsWhat then does the gnostic matrix repeating do when we look back to Deleuze? Ultimately out of the scope of this paper to cover all implications, my aim has been to explore one manner in which Laruelle’s non-philosophy does not simply break from Deleuze’s philosophy, but opens an inverse operation of difference. The repetition of the gnostic matrix does not preclude or prevent the notion of different itself, but rather, reformulates it as non primary. Instead of the primary mode of production of all things in the world (i.e., the remainders of God’s calculator), what does difference in-itself become in light of a gnostic matrix repeating under-determinancy? We might see the repetition of the gnostic matrix, its under-going, as not only an inverse function of Deleuze’s difference itself but further as a type of sublimation of it. Deleuze describes of difference, “It is mediated, it is itself mediation, the middle term in person. It is productive, since genera are not divided into differences but divided by differences which give rise to corresponding species” and also that “it is attributed to the species but at the same time attributes the genus to it and constitutes the species to which it is attributed. Such a synthetic and constitutive predicate . . . has one final property: that of carrying with itself that which it attributes” (DR, 31). As such, difference itself has an inherent structure that determines its own divergent-ness. Whence the divergent-ness of difference itself? What is the structure of it as a predicate that can be both mediated and itself mediation, carrying with it its own attributes? Might this instead be thought more specifically as a matrix? A matrix structure that is able to describe difference that itself contains difference in a skeletal and under-determined structure, and thus as its own container separates axiomatic parts that are simultaneously a containment of the whole matrix. Difference as a matrix is in this way not only difference itself as a function of its structure, but describes further the axiomatic condition of difference containing in itself what it attributes. John Protevi bolsters this claim in his suggestion that “you could replace the title Difference and Repetition with Structure and Genesis: structures are differential, and genesis produces repetition: different incarnations of the same structure” (Protevi, 39). Seen as different incarnations of its ‘structure,’ difference as within a matrix becomes not differential but a matrixial form that contains difference. It is thus the structure of the matrix that repeats, which is a sameness of repeating, and is what Laruelle describes. In this way, difference is sublimated to the matrix (‘structure’), albeit in an undetermined skeleton and uncertain form, and this underdetermined sameness of the matrix is what repeats. The quantum theology of the gnostic matrix is the manner that allows for indiscernibility to be the condition of an underdetermined Idea and is what difference itself is then contained within. 4.0 Conclusion: The Shadow of the Matrix of the People to ComeLooking back to where I began on the last page of What is Philosophy, after Deleuze and Guattari say that every philosophy needs a non-philosophy, the last two sentences of the book go on to say: “if the three Nos are still distinct in relation to the cerebral plane, they are no longer distinct in relation to the chaos into which the brain plunges. In this submersion it seems that there is extracted from chaos the shadow of the ‘people to come’” and that “It is here that concepts, sensations, and functions become undecidable, at the same time as philosophy, art, and sciencebecome indiscernible, as if they shared the same shadow ”(WP, 218, my italics). Deleuze and Guattari point out here that when chaos is no longer on the outside, when it is inside and across planes of thought instead, we begin in an indiscernibility, in line with what Laruelle says of chaos itself as philosophical disturbance rather than at philosophy’s edge . The indiscernible does not dangle at a threshold in a place between philosophy and chaos, because it is within and extracted from chaos. For Deleuze and Guattari, it seems we can extract a shadow from it, not as a shadow differentiated through intensity or by the function of difference itself, but through a shared sameness of indiscernibility. What is this other non-process for the extraction of Deleuze and Guattari’s shared same-shadow? But this is where the book ends. Where Deleuze and Guattari end, Laruelle continues. A shared shadow is a shared repetition of sameness, not the shadows of Plato or simulacra. It is a shared basement, a debasement, the generic sameness condition repeating. In this way, a shadow extracted from chaos begins out of a non-philosophy. The shared shadow of indiscernibility is the shadow of a gnostic matrix. Lastly, on the people to come: the repetition of the generic gnostic matrix allows for us to say two things. That immanence is living the generic same shadow, and that transcendence is a ‘fallen-into-immanence’ without having fallen from a Ideal into an extension of a shadow (CF, 172). It is in the gnostic matrix, out of which we do not philosophize in decision, or as Laruelle says, it is “not a conceptual or discursive entity, an atom in the transcendent sense, but a discreteand indivisible quantum of messianity. It is at once a drive, the raising of a cry … the exclamation of a mystic” (CF, 154). ‘The people to come’ from Deleuze and Guattari, when out of a shared shadow thus come differently. They are now Laruelle’s messiahs that emanate. As implied by Deleuze and Guattari as well, what is to come is thus not by the repetition of the structure of difference, but with an underdetermined repetition of sameness. It is the shared shadow of the gnostic matrix in which the people to come will be matrixially repeated. 1. Deleuze wrote in ‘Letter to a Harsh Critic’ about his method of “sneaking up behind” a philosophical concept and producing a monstrous offspring, “I saw myself as taking an author from behind and giving him a child that would be his own offspring, yet monstrous.” (Negotiations, 4) Works Cited Deleuze, Gilles and Felix Guattari. What is Philosophy? Translated by Hugh Tomlinson and Graham Burchill, Verso, 1994. Deleuze, Gilles. Difference and Repetition. 1968. Translated by Paul Patton, Columbia University Press, 1994. – – – . Negotiations 1972-1990. Translated by Martin Joughin, Columbia University Press, 1995. Laruelle, François. Christo-Fiction: The Ruins of Athens and Jerusalem. Translated by Robin Mackay, Columbia University Press, 2015. – – -. From Decision to Heresy: Experiments in Non-Standard Thought. ‘Letter to Deleuze’, 1988, translated by Robin Mackay, Urbanomic, 2012. – – -. Philosophy and Non-Philosophy. 1989. Translated by Taylor Adkins, Univocal, 2013. – – -. Principles of Non-Philosophy. 1996. Translated by Nicola Rubczak and Anthony Paul Smith, Bloomsbury, 2013. Protevi, John. “An approach to Difference and Repetition.” Journal of Philosophy: A Cross Disciplinary Inquiry. 5.11 (2010): 35. The essay is taken from: by Steven Craig Hickman The attitude of the Gnostics toward time, and more generally, toward the world, is characterized from the first by a movement of revolt against time and the world as conceived by Hellenism and Christianity… —Henri-Charles Puech, Gnosis and Time Most of us think of time as a linear process, a movement from the past to the future, but has this always been so? Is time truly an arrow, or is it also a return, a circle rather than a slide toward some apocalyptic abyss? Or, what if time could reverse course, or slip off into a non-time, a time of no time, a rhizomatic cleavage in time that would lock it and its inhabitants in a zone of stasis, a place where time stood still? Have we even begun to think about time? The earliest recorded Western philosophy of time was expounded by the ancient Egyptian thinker Ptahhotep (c. 2650–2600 BC), who said, “Do not lessen the time of following desire, for the wasting of time is an abomination to the spirit.” The Vedas, the earliest texts on Indian philosophy and Hindu philosophy, dating back to the late 2nd millennium BC, describe ancient Hindu cosmology, in which the universe goes through repeated cycles of creation, destruction, and rebirth, with each cycle lasting 4,320,000 years. Ancient Greek philosophers, including Parmenides and Heraclitus, wrote essays on the nature of time. Plato, in the Timaeus, identified time with the period of motion of the heavenly bodies, and space as that in which things come to be. Aristotle, in Book IV of his Physics, defined time as the number of changes with respect to before and after, and the place of an object as the innermost motionless boundary of that which surrounds it. In Book 11 of St. Augustine’s Confessions, he ruminates on the nature of time, asking, “What then is time? If no one asks me, I know: if I wish to explain it to one that asketh, I know not.” During the Medieval period with the influx of ancient Greek systems from the great philosophers and mystics of Islam came other concepts of Time. The Islamic world at the time was so large, and the intellectual milieu so rich and diverse, that no single book could put an end to its philosophy and discursive reasoning. Ibn ‘Arabī’s philosophical mysticism offers a vast synthesis of gnostic and Sufi ideas as well as a type of philosophical discourse which, for the first time, formulates the Sufi doctrine. With Ibn ‘Arabī, we see a monumental effort to comment on a full array of metaphysical, cosmological, and psychological aspects of Gnosticism, thereby providing a vision of reality whose attainment requires the practice of the Sufi path. Ibn ‘Arabī’s philosophico-mystical edifice is a process of spiritual hermeneutics (ta’wīl) which relies on the language of symbolism to guide a novice from the exterior (ẓāhir) to the interior (bāṭin). For Ibn ‘Arabī, the entire cosmos represents signs (ayāt) which lend themselves to symbolic exegesis, a process whose pinnacle is the Universal Man (al-insān al-kāmil). Ibn ‘Arabī, whose doctrine of the Unity of Being (waḥdat al-wūjūd) has been interpreted by many to be pantheism, was nevertheless careful to argue that even though God dwells in things, but the world “is not” in God. For Ibn ‘Arabī, humans are microcosms and the universe is the macrocosm; the Universal Man is the one who realizes all of his inherent potentialities, including the Divine breath which was blown into man by God in the beginning of creation as the Qur’an says. As the modern scholar Henri Corbin would say of Islamic Gnosticism and Sufi notions of Time: “Real time is concrete time, the time of persons. The abstract time of “everyone and no one” abolishes pluralism and makes totalitarianisms possible. The “No!” that he insists we cry aloud “draws its energy from the lightning flash whose vertical joins heaven with earth, not from some horizontal line of force that loses itself in a limitlessness from which no meaning arises.”1 This battle between concrete time of persons, and the abstract time or totalitarian time of the State or Sovereign power and authoritarian rule was at heart a war between monism and pluralism, autarchy and democracy. For Corbin the Gnostics and their descendants in Sufic thought our time is a “time of return,” and the beings of Light who inhabit this time are haunted by intimations of Eternity and nostalgia for the source of Light … (Cheethem, p. 45) This notion that the whole of history is and has been a defensive measure against the dark side of Time, that we have already been thrown into this temporal continuum to not to condemn us but to protect us from the dark powers of Ahriman, the alien and evil power of Darkness who originates entirely outside the realm of Light in an unknowable outer abyss. That the God of Light and Eternity, the Time of Endlessness needed time to do battle against the dark one so formed and shaped this universe of finitude to stay the hand of the evil one. And, yet, it is the very power of the Evil One who is locked within the energetic multiplicity of this universes powers of mattering through the fallen labors of Sophia, the mother of all and Time. The time that we know is both necessitated and limited by the acts in the cosmic drama that is both its prelude and its consummation. We live in “cyclical time”— a time of a return to an eternal origin. In this mythology the earthly soul is lacking its eternal half (Plato) — it is “lagging behind itself,” incomplete and confined within the limited time of the combat. The earthly soul lives in nostalgia and anticipation, in exiled incompleteness, in longing and hope. (Cheetham, pp. 44-46) These mythical notions of time would fall away during the time of destruction, the age of demythologization we have come to know of as the Enlightenment. Secular time and the sciences would displace these ancient narratives and dramatizations of Time as part of this demythologization process. For Kant the watershed philosopher of the Secular Age time and space were neither objective nor real: Space is not something objective and real, nor a substance, nor an accident, nor a relation; instead, it is subjective and ideal, and originates from the mind’s nature in accord with a stable law as a scheme, as it were, for coordinating everything sensed externally.2 Kant would begin that epistemic turn toward the Mind and make both Space and Time categories of the Mind rather than ontological verities of existence, so that our conceptions of outer sense were from then own dependent on Mind rather than autonomous substances in their own right. This would be the beginning of what we now know as the Anti-Realist Continental traditions in which all thought of reality independent of the Mind would lose its relevancy within philosophy. This abstraction of time out of the real and substantive would lock us into a realm of pure evil according to Corbin and the Ismaili Sufi gnostics. Whereas for the ancient gnostics Time (Zervan) was a Person, the modern cosmologies of the West have abstracted themselves out of the Real, produced a cut or gap or crack between the human and the universe at large displacing humanity into a realm of no-time, an internalized time of abstraction and probabilities, linearity and progression in which time is no longer cyclic and moving toward its origins, a return. But is now a time cut off in abstract time, a time of no-time in which humanity in its accumulation of abstractions seeks to stay the return of Time. Instead of combating the dark side of Time modernity seeks to join the dark side and contribute to its war against return, against origins and the Real. Of course all of this is mystical mumbo-jumbo, a record of the mythologies of peoples star games and strategies of explaining time as a personal soteriology, a salvationist mythology in which humanity is seen as a pawn in an eternal war between Light and Dark, Good and Evil. As if we were members of a spiritual species that had been trapped and imprisoned in a realm of dark abstractions our memories lost in the deep well of past time. This notion that the cosmic drama of a cyclical time originating in a retardation of some dark progenitor (Ahriman) is carried toward its final act by “the torment of a ‘retarded eternity.’ (Cheetham, p. 49) As if the God of Light were neither all powerful, nor had the weapons available to combat this dark pull and lure of evil. As if the dark powers were in fact much older and powerful that this upstart, this demiurgic force who contested its ancient darkness. In modern quantum cosmology we speak of the impossible mathematical models of those missing particles needed to explain the twelve or so dimensions of our universe under the rubric of Dark Matter and Dark Energy. Why? What is this dark unknown force and its spectral material that seems to both engender our visible universe and stabilize and organize its substantive systems? We know little, and surmise much. Modern cosmology has spent over a hundred years seeking a theory of everything to fit all the missing pieces of time and space, the spacetime continuum together in a mathematical model that can be someday tested to put to sleep the questions of both the origins and end of our universe. While explaining the very structure and dynamism of that process of Time and its powers in the substance of space. The late Mark Fisher in his Capitalist Realism brought many of these feelings and suspicions of the ancient gnostics to the fore as he studied the catastrophic consequences of late capitalism: the suspicion that the end has already come, the thought that it could well be the case that the future harbors only reiteration and re-permutation. Could it be that there are no breaks, no ‘shocks of the new’ to come? Such anxieties tend to result in a bi-polar oscillation: the ‘weak messianic’ hope that there must be something new on the way lapses into the morose conviction that nothing new can ever happen.3 This is the heaviness and moroseness of the gnostic view of evil, of the realization that cut off in time we are trapped in a system of domination that harbors our ill-will and seeks to enslave us in a global system under the rule of absolute abstract Time. As Fisher explicating T.S. Eliot’s The Wasteland would tell us “the exhaustion of the future does not even leave us with the past. Tradition counts for nothing when it is no longer contested and modified. A culture that is merely preserved is no culture at all.” (Fisher, p. 7) A sense of despair and hopelessness ensues and we are bound to a world without past or future, cut off in a sidereal time of no-time; neither utopic, nor real, but rather a dystopic time of pain and suffering under archons of political and social control that seek total dominion over all life. We are living through a “transformation of culture into museum pieces” (Fisher, p. 8). Fisher asks us to imagine walking: around the British Museum, where you see objects torn from their lifeworlds and assembled as if on the deck of some Predator spacecraft, and you have a powerful image of this process at work. In the conversion of practices and rituals into merely aesthetic objects, the beliefs of previous cultures are objectively ironized, transformed into artifacts. Capitalist realism is therefore not a particular type of realism; it is more like realism in itself. (Fisher, p. 8) This notion that humanity is living in a museum under the gaze of invisible archons whose pleasure is in tormenting us within a planetary experiment of absolute torturescapes, playing out the eternal round of a time of no-time where our torments produce the pleasure and jouissance of strange Time-Lords: this is the horrendous message of a dark gnosis in which there is no reprieve, a sadism of ancient powers from which there is no redemption. Of course for most of humanity none of this is perceived for as T.S. Eliot once said in a poem: “Humankind cannot bare too much reality.” (Four Quartets). Instead we have our local myths, our secret narratives and illusions, our delusions of grace and innocence to alleviate such dark truths. We shift between non-meaning, either passive or active nihilism, or the elder days of religious or political meanings of earthly power and corruption; else, the natural power of entropy and death of the scientific view… we sleep in a world of delirium believing we are awake to the truth of the Real. Others like my friend R. Scott Bakker pull the skeptical worldview out of the bag of ancient thought and update it for a new era with truths of brain sciences that speak of our ignorance, our ‘medial neglect’ in which humans by way of evolution evolved mental systems to help them survive and procreate over millennia in developing shared delusions and mental worlds full of errors to assuage the dark outer truth of our non-knowledge of ourselves and the environment surrounding us. Like magicians and shamans we dream of power and knowledge, but live in a realm or error and erroneous delusions, mental fallacies of reason and cognitive biases. As Fisher would tell it what we are left with in our time is ruins: “Capitalism is what is left when beliefs have collapsed at the level of ritual or symbolic elaboration, and all that is left is the consumer-spectator, trudging through the ruins and the relics.” (Fisher, p. 8) Like zombies or ghosts we sleepwalk through existence, circle in this time of no-time, live out our lives as if this were all there was, as if this were real, the only world, the only way. Lost among our own delusions we accumulate profits for our masters as if we had no alternative, all the while being tormented by the disquieting thought that we have forgotten something profound and if we could just remember what it is we might suddenly wake up from this nightmare of civilization and history. John Gray studying the Aztec civilization discovers another version of this overcoming of the evil of Time. For the Aztecs humans were fated to live in a world in which their rulers were their enemies, their gods were their enemies. Yet these same enemies ensured a type of order that would not otherwise be possible. If Hobbes had been right in his diagnosis of human conflict producing savagery and brutishness, Aztec life could only be a brutish anarchy, without art, industry or letters. The actuality was the thriving metropolis full of order, beauty, and artistic excellence that so amazed the invading Spaniards. Destroyed soon after the conquistadores arrived, the Aztec city was an experimental refutation of some of the most fundamental assumptions of modern western ethics and politics.4 The alien quality of the Aztec world does not come simply from the fact that they made a spectacle of killing. The Romans did as much in their gladiatorial games, but they did so for the sake of entertainment. The uncanniness of the Aztecs comes from the fact that they killed in order to create meaning in their lives. It is as if by practising human sacrifice as they did the Aztecs were unveiling something that in our world has been covered up. Modern humanity insists violence is inhuman. Everyone says nothing is dearer to them than life – except perhaps freedom, for which some assert they would willingly die. Many have been ready to kill on an enormous scale for the sake of creating a future in which no one dies of violence. There are also some convinced that violence is fading away. All say they want an end to the slaughter of humans by other humans that has shaped the course of history. The Aztecs did not share the modern conceit that mass killing can bring about universal peace. They did not envision any future when humans ceased to be violent. When they practised human sacrifice it was not to improve the world, still less to fashion some higher type of human being. The purpose of the killing was what they affirmed it to be: to protect them from the senseless violence that is inherent in a world of chaos. That human sacrifice was a barbarous way of making meaning tells us something about ourselves as much as them. Civilization and barbarism are not different kinds of society. They are found – intertwined – whenever human beings come together. (Gray, p. 87) Again we see this use of violence against the violence of Time, a revolt against the crushing order of the chaosmos or thermospasm of existence in which we find ourselves locked up like rats in a maze without outlet. Humans kill one another – and in some cases themselves – for many reasons, but none is more human than the attempt to make sense of their lives. More than the loss of life, they fear loss of meaning. There are many who prefer dying to some kinds of survival, and quite a few that have chosen to go to a violent end. (Gray, p. 87) Marx himself would see this dark god of violence at work in the 19th Century, saying, “We have seen how this absolute contradiction does away with all repose, all fixity and all security as far as the worker’s life-situation is concerned; how it constantly threatens, by taking away the instruments of labour, to snatch from his hands the means of subsistence, and, by suppressing his specialized function, to make him superfluous. We have seen, too, how this contradiction bursts forth without restraint in the ceaseless human sacrifices required from the working class, in the reckless squandering of labour-powers, and in the devastating effects of social anarchy.”5 For Marx modern society was a continuous sacrifice by the poor workers to the gods of violence and profit so that the elite could feed off the surplus value of their immolation. As Franco “Bifo” Berardi in Heroes: Mass Murder and Suicide would suggest it is not merely crime and suicide, but more broadly the establishment of a kingdom of nihilism and the suicidal drive that is permeating contemporary culture, together with a phenomenology of panic, aggression and resultant violence.6 For Berarid the recent rash of mass suicides and mass murder in the heart of the capitalist state economies in EU and the U.S.A. are about people who are suffering themselves, and who become criminals because this is their way both to express their psychopathic need for publicity and also to find a suicidal exit from their present hell. (Berardi, IL 60) As he states it: I’m interested in people who are suffering themselves, and who become criminals because this is their way both to express their psychopathic need for publicity and also to find a suicidal exit from their present hell. The point for Berardi is that of the Aztecs who sought to create meaning out of the mass killings of it’s victims, victims who were the doubled face of the enemy, the enemy who was god, the god of violence of which the sacrifice and sacrificed were the dual face of the Dark Lord of Time. Ahriman – the violent one. Conversely, for Berardi our late capitalist era seeks to annihilate nihilism actively destroying the shared values (both moral and economic values) produced not in the present, but in the past by the human production of democratic political regulation under progressive liberal systems of managed societies of control. They do this to affirm the order of chaos and the primacy of the abstract force of money: the power of the absolute god of violence. Annihilating nihilism is the product of financial capitalism, destroying concrete wealth in order to accumulate abstract value. Ultimately, the financial game is based on the premise that the value of money invested will increase as things are annihilated (if factories are dismantled, jobs destroyed, people die and are sacrificed, cities crumble, etc.), that the god of violence will be appeased and the financial elite can continue their devastation of the human and natural worlds in an endless hyperloop outside time’s vectors. For those outside the loop this daemonic farce is the epitome of the ancient gnostic myth: financial capital as the ideal form of a Cosmic Crime, actively establishing suicide at the core of the sociopathic end game of Western Civilization.