|

by Himanshu Damle

Let κa be a smooth field on our background spacetime (M, gab). κa is said to be a Killing field if its associated local flow maps Γs are all isometries or, equivalently, if £κ gab = 0. The latter condition can also be expressed as ∇(aκb) = 0.

Any number of standard symmetry conditions—local versions of them, at least can be cast as claims about the existence of Killing fields. Local, because killing fields need not be complete, and their associated flow maps need not be defined globally.

(M, gab) is stationary if it has a Killing field that is everywhere timelike.

(M, gab) is static if it has a Killing field that is everywhere timelike and locally hypersurface orthogonal. (M, gab) is homogeneous if its Killing fields, at every point of M, span the tangent space.

In a stationary spacetime there is, at least locally, a “timelike flow” that preserves all spacetime distances. But the flow can exhibit rotation. Think of a whirlpool. It is the latter possibility that is ruled out when one passes to a static spacetime. For example, Gödel spacetime, is stationary but not static.

Let κa be a Killing field in an arbitrary spacetime (M, gab) (not necessarily Minkowski spacetime), and let γ : I → M be a smooth, future-directed, timelike curve, with unit tangent field ξa. We take its image to represent the worldline of a point particle with mass m > 0. Consider the quantity J = (Paκa), where Pa = mξa is the four-momentum of the particle. It certainly need not be constant on γ[I]. But it will be if γ is a geodesic. For in that case, ξn∇nξa = 0 and hence.

ξn∇nJ = m(κa ξn∇nξa + ξnξa ∇nκa) = mξnξa ∇(nκa) = 0

Thus, J is constant along the worldlines of free particles of positive mass. We refer to J as the conserved quantity associated with κa. If κa is timelike, we call J the energy of the particle (associated with κa). If it is spacelike, and if its associated flow maps resemble translations, we call J the linear momentum of the particle (associated with κa). Finally, if κa is spacelike, and if its associated flow maps resemble rotations, then we call J the angular momentum of the particle (associated with κa).

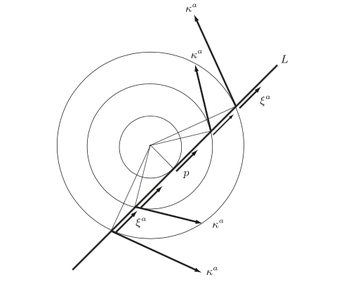

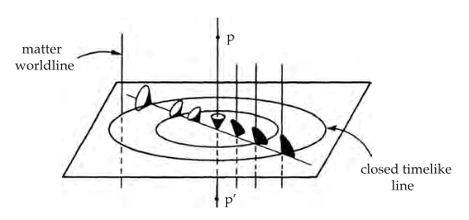

It is useful to keep in mind a certain picture that helps one “see” why the angular momentum of free particles (to take that example) is conserved. It involves an analogue of angular momentum in Euclidean plane geometry. Figure below shows a rotational Killing field κa in the Euclidean plane, the image of a geodesic (i.e., a line) L, and the tangent field ξa to the geodesic. Consider the quantity J = ξaκa, i.e., the inner product of ξa with κa – along L, and we can better visualize the assertion.

Figure: κa is a rotational Killing field. (It is everywhere orthogonal to a circle radius, and is proportional to it in length.) ξa is a tangent vector field of constant length on the line L. The inner product between them is constant. (Equivalently, the length of the projection of κa onto the line is constant.)

Let us temporarily drop indices and write κ·ξ as one would in ordinary Euclidean vector calculus (rather than ξaκa). Let p be the point on L that is closest to the center point where κ vanishes. At that point, κ is parallel to ξ. As one moves away from p along L, in either direction, the length ∥κ∥ of κ grows, but the angle ∠(κ,ξ) between the vectors increases as well. It should seem at least plausible from the picture that the length of the projection of κ onto the line is constant and, hence, that the inner product κ·ξ = cos(∠(κ , ξ )) ∥κ ∥ ∥ξ ∥ is constant.

That is how to think about the conservation of angular momentum for free particles in relativity theory. It does not matter that in the latter context we are dealing with a Lorentzian metric and allowing for curvature. The claim is still that a certain inner product of vector fields remains constant along a geodesic, and we can still think of that constancy as arising from a compensatory balance of two factors.

Let us now turn to the second type of conserved quantity, the one that is an attribute of extended bodies. Let κa be an arbitrary Killing field, and let Tab be the energy-momentum field associated with some matter field. Assume it satisfies the conservation condition (∇aTab = 0). Then (Tabκb) is divergence free:

∇a(Tabκb) = κb∇aTab + Tab∇aκb = Tab∇(aκb) = 0 (The second equality follows from the conservation condition and the symmetry of Tab; the third follows from the fact that κa is a Killing field.) It is natural, then, to apply Stokes’s theorem to the vector field (Tabκb). Consider a bounded system with aggregate energy-momentum field Tab in an otherwise empty universe. Then there exists a (possibly huge) timelike world tube such that Tab vanishes outside the tube (and vanishes on its boundary).

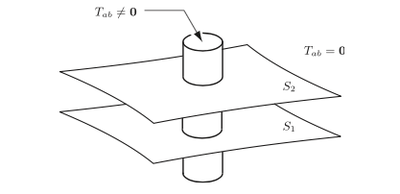

Let S1 and S2 be (non-intersecting) spacelike hypersurfaces that cut the tube as in the figure below, and let N be the segment of the tube falling between them (with boundaries included).

Figure: The integrated energy (relative to a background timelike Killing field) over the intersection of the world tube with a spacelike hypersurface is independent of the choice of hypersurface.

By Stokes’s theorem,

∫S2(Tabκb)dSa – ∫S1(Tabκb)dSa = ∫S2∩∂N(Tabκb)dSa – ∫S1∩∂N(Tabκb)dSa = ∫∂N(Tabκb)dSa = ∫N∇a(Tabκb)dV = 0

Thus, the integral ∫S(Tabκb)dSa is independent of the choice of spacelike hypersurface S intersecting the world tube, and is, in this sense, a conserved quantity (construed as an attribute of the system confined to the tube). An “early” intersection yields the same value as a “late” one. Again, the character of the background Killing field κa determines our description of the conserved quantity in question. If κa is timelike, we take ∫S(Tabκb)dSa to be the aggregate energy of the system (associated with κa). And so forth.

One thought on “Killing Fields”

[…] dotted circle has radius rc. Once again, that is the “critical radius” at which the rotational Killing field φa is null. Call this dotted circle the “critical circle.” The circles that pass through p and […]

0 Comments

LECTURES BY GILLES DELEUZE Intervention of Comtesse: (inaudible on the cassette). Gilles: I feel coming between you and me still a difference. You tend very quickly to stress an authentically Spinozist concept, that of the tendency to persevere in being. The last time, you spoke to me about the conatus, i.e. the tendency to persevere in being, and you asked me: what don't you do it? I responded that for the moment I cannot introduce it because, in my reading, I am stressing other Spinozist concepts, and the tendency to persevere in being, I will derive it from other concepts which are for me the essential concepts, those of power (puissance) and affect. Today, you return to the same theme. There is not even room for a discussion, you would propose another reading, i.e. a differently accentuated reading. As for the problem of the reasonable man and the insane man, I will respond exactly thus: what distinguishes the insane person and the reasonable one according to Spinoza, and conversely at the same time, there is: what doesn't distinguish them? From which point of view can they not be distinguished, from which point of view do they have to be distinguished? I would say, for my reading, that Spinoza‚s response is very rigorous. If I summarize Spinoza‚s response, it seems to me that this summary would be this: from a certain point of view, there is no reason to make a distinction between the reasonable man and the insane person. From another point of view, there is a reason to make a distinction. Firstly, from the point of view of power, there is no reason to introduce a distinction between the reasonable man and the insane man. What does that mean? Does that mean that they have the same power? No, it doesn‚t mean that they have the same power, but it means that each one, as much as there is in him, realises or exercises his power. I.e. each one, as much as there is in him, endeavours [s‚efforce] to persevere in his being. Therefore, from the point of view of power, insofar as each, according to natural right, endeavours to persevere in his being, i.e. exercise his power ˜ you see I always put Œeffort‚ between brackets ˜ it is not that he tries to persevere, in any way, he perseveres in his being as much as there is in him, this is why I do not like the idea of conatus, the idea of effort, which does not translate Spinoza‚s thought because what it calls an effort to persevere in being is the fact that I exercise my power at each moment, as much as there is in me. It is not an effort, but from the point of view of power, therefore, I can not at all say what each one is worth, because each one would have the same power, in effect the power of the insane man is not the same as that of the reasonable one, but what there is in common between the two is that, whatever the power, each exercises his own. Therefore, from this point of view, I would not say that the reasonable man is better than the insane one. I cannot, I have no way of saying that: each has a power, each exercises as much power as there is in him. It is natural right, it is the world of nature. From this point of view, I could not establish any difference in quality between the reasonable man and the insane one. But from another point of view, I know very well that the reasonable man is Œbetter‚ than the insane one. Better, what does that mean? More powerful, in the Spinozist sense of the word. Therefore, from this second point of view, I must make and I do make a distinction between the reasonable man and the insane one. What is this point of view? My response, according to Spinoza, would be exactly this: from the point of view of power, you have no reason to distinguish the reasonable man and the insane one, but from the other point of view, namely that of the affects, you distinguish the reasonable man and the insane one. From where does this other point of view come? You remember that power is always actual, it is always exercised. It is the affects that exercise them. The affects are the exercises of power, what I experience in action or passion, it is this which exercises my power, at every moment. If the reasonable man and the insane one are distinguished, it is not by means of power, each one realises his power, it is by means of the affects. The affects of the reasonable man are not the same as those of the insane one. Hence the whole problem of reason will be converted by Spinoza into a special case of the more general problem of the affects. Reason indicates a certain type of affect. That is very new. To say that reason is not going to be defined by ideas, of course, it will also be defined by ideas. There is a practical reason that consists in a certain type of affect, in a certain way of being affected. That poses a very practical problem of reason. What does it mean to be reasonable, at that moment? Inevitably reason is an ensemble of affects, for the simple reason that it is precisely the forms under which power is exercised in such and such conditions. Therefore, to the question that has just been posed by Comtesse, my response is relatively strict; in effect, what difference is there between a reasonable man and the insane one? From a certain point of view, none, that is the point of view of power. From another point of view, enormous difference, from the point of view of the affects which exercise power. Intervention of Comtesse. Gilles: You note a difference between Spinoza and Hobbes and you are quite right. If I summarize it, the difference is this: for the one as for the other, Spinoza and Hobbes, one is careful to leave the state of nature by a contract. But in the case of Hobbes, it is in effect a contract by which I give up my right of nature. I‚ll specify because it is more complicated: if it is true that I give up my natural right, then on the other hand, the sovereign himself does not also give up his. Therefore, in a certain way, the right of nature is preserved. For Spinoza, on the contrary, in the contract I do not give up my right of nature, and there is Spinoza‚s famous formula given in a letter: I preserve the right of nature even in the civil state. This famous formula of Spinoza clearly means, for any reader of the era, that on this point, I break with Hobbes. In a certain way, he also preserved natural right in the civil state, but only to the advantage of the sovereign. I say that too quickly. Spinoza, on the whole, is a disciple of Hobbes. Why? Because on two general but fundamental points, he entirely follows the Hobbesian revolution, and I believe that Spinoza‚s political philosophy would have been impossible without the kind of intervention that Hobbes had introduced into political philosophy. What is this very, very important double intervention, this extraordinary innovation? It is, first innovation, to have conceived the state of nature and natural right in a way that broke entirely with the Ciceronian tradition. Now, on this point, Spinoza entirely ratifies Hobbes‚ revolution. Second point: consequently, to have substituted the idea of a pact of consent as the foundation of the civil state for the relation of competence such as it was in traditional philosophy, from Plato to Saint Thomas. Now, on these two fundamental points, the civil state can only refer to a pact of consent and not to a relation of competence where there would be a superiority of the sage, and the whole conception, in addition, of the state of nature and of natural right as power and exercise of power, these two fundamental points belong to Hobbes. It is according to these two fundamental points that I would say that the obvious difference that Comtesse has just signaled between Spinoza and Hobbes, presumes and can only be inscribed in one preliminary resemblance, a resemblance by which Spinoza follows the two fundamental principles of Hobbes. This then becomes a balancing of accounts between them, but within these new presuppositions introduced into political philosophy by Hobbes. We will be led to speak about Spinoza‚s political conception this year from the point of view of research that we are doing on Ontology: in what sense can Ontology entail or must it entail a political philosophy? Do not forget that there is a whole political path of Spinoza, I‚m going very quickly. A very fascinating political path because we cannot even read one political book of Spinoza‚s philosophy without understanding what problems it poses, and what political problems he lived through. The Netherlands in the era of Spinoza was not simple and all Spinoza's political writings are very connected to this situation. It is not by chance that Spinoza wrote two books on political philosophy, one the Theologico-Political Treatise the other the Political Treatise, and that, between the two, enough things happened such that Spinoza evolved. The Netherlands in that era was torn between two tendencies. There was the tendency of the House of Orange, and then there was the liberal tendency of the De Witt brothers. Now the De Witt brothers, under very obscure conditions, had won at one moment. The House of Orange was not nothing: this put into play the relations of foreign policy, relations with Spain, war or peace. The De Witt brothers were basically pacifists. This put into play the economic structure, the House of Orange supported the large companies, the brothers were very hostile to the large companies. This opposition stirred everything up. Now the De Witt brothers were assassinated in absolutely horrible circumstances. Spinoza felt this as really the last moment in which he could no longer write, this could also happen to him. The De Witt brothers‚ entourage protected Spinoza. This dealt him a blow. The difference in political tone between the Theologico-Political Treatise and the Political Treatise is explained because, between the two, there was the assassination, and Spinoza no longer believed in what he had said before, in the liberal monarchy. His political problem arises in a very beautiful, still very current, way; yes, there is only a political problem that it would be necessary to try to understand, to make ethics into politics. To understand what? To understand why people fight for their slavery. They seem to be so content to be slaves, that they will do anything to remain slaves. How to explain such a thing? It fascinates him. Literally, how to explain that people don't revolt? But at the same time, revolt or revolution, you will never find that in Spinoza. We‚re saying very silly things. At the same time, he made drawings. There is a reproduction of a drawing of his that is a very obscure thing. He had drawn himself in the form of a Neapolitan revolutionary who was well-known in that era. He had included his own head. It is odd. Why does he never speak about revolt or revolution? Is it because he is a moderate? Undoubtedly, he must be a moderate; but let us suppose that he is a moderate. But at that time, even the extremists hesitated to speak of revolution, even the leftists of the era. And Collegians who were against the church, these Catholics were near enough to what we would call today the Catholics of the extreme left. Why isn‚t revolution discussed? There is a silly thing that is said, even in the handbooks of history, that there was no English revolution. Everyone knows perfectly well that there was an English revolution, the formidable revolution of Cromwell. And Cromwell‚s revolution is an almost pure case of a revolution that was betrayed as soon as it was done. The whole of the seventeenth century is full of reflections on how a revolution can not be betrayed. Revolution was always thought by revolutionaries in terms of how it is that such things are always betrayed. Now, the recent example for Spinoza‚s contemporaries is the revolution of Cromwell, who was the most fantastic traitor to the revolution that Cromwell himself had imposed. If you take, well after English Romanticism, it is a fantastic poetic and literary movement, but it is an intense political movement. The whole of English Romanticism is centered on the theme of the betrayed revolution. How to live on when the revolution has been betrayed and seems destined to be betrayed? The model that obsessed the great English Romantics was always Cromwell. Cromwell lived in that era as Stalin did today. Nobody speaks about revolution, not at all because they do not have an equivalent in mind, it is for a very different reason. They won‚t call that revolution because the revolution is Cromwell. Now, at the time of the Theologico-Political Treatise, Spinoza still believed in a liberal monarchy, on the whole. This is no longer true from the Political Treatise. The De Witt brothers were assassinated, compromise is no longer possible. Spinoza gives up publishing the Ethics, he knows that it‚s screwed. At that moment, it seems that Spinoza would have tended much more to think about the chances of a democracy. But the theme of democracy appears much more in the Political Treatise than in the Theologico-Political Treatise, which remained in the perspective of a liberal monarchy. What would a democracy be at the level of the Netherlands? It is what was liquidated with the assassination of the De Witt brothers. Spinoza dies, as if symbolically, when he is at the chapter Œdemocracy‚. We will never know what he would have said. There is a fundamental relation between Ontology and a certain style of politics. What this relation consists of, we don‚t yet know. What does a political philosophy which is placed in an ontological perspective consist of? Is it defined by the problem of the state? Not especially, because the others too. A philosophy of the One will also pass by way of the problem of the state. The real difference does not appear elsewhere between pure ontologies and philosophies of the One. Philosophies of the One are philosophies that fundamentally imply a hierarchy of existing things, hence the principle of consequence, hence the principle of emanation: from the One emanates Being, from Being emanates other things, etc. the hierarchies of the Neo-Platonists. Therefore, the problem of the state, they will encounter it when they encounter themselves? at the level of this problem: the institution of a political hierarchy. Among Neo-Platonists, there are hierarchies everywhere, there is a celestial hierarchy, a terrestrial hierarchy, and what the Neo-Platonists call hypostases are precisely the terms in the institution of a hierarchy. What appears to me striking in a pure ontology is the point at which it repudiates the hierarchies. In effect, if there is no One superior to being, if being is said of everything that is and is said of everything that is in one and the same sense, this is what appeared to me to be the key ontological proposition: there is no unity superior to being and, consequently, being is said of everything that of which it is said, i.e. is said of everything that is, is said of all being [étant], in one and the same sense. It is the world of immanence. This world of ontological immanence is an essentially anti-hierarchical world. Of course, it is necessary to correct: these philosophers of ontology, we will say that evidently a practical hierarchy is needed, ontology does not lead to formulas which would be those of nihilism or non-being, of the type where everything is the same [tout se vaut]. And yet, in certain regards, everything is the same, from the point of view of an ontology, i.e. the point of view of being. All being [étant] exercises as much being [être] as there is in it. That‚s all there is to it. It is anti-hierarchical thought. It is almost a kind of anarchy. There is an anarchy of beings in being. It is the basic intuition of ontology: all beings are the same [se valent]. The stone, the insane, the reasonable, the animal, from a certain point of view, from the point of view of Being [être], they are the same. Each is as much as there is in it, and being is said in one and the same sense of the stone, of the man, of the insane, of the reasonable. It is a very beautiful idea. It is a very savage kind of world. With that, they encounter the political domain, but the way in which they will encounter the political domain depends precisely on this kind of intuition of equal being, of anti-hierarchical being. And the way in which they think the state is no longer the relation of somebody who commands and others who obey. In Hobbes, the political relation is the relation of somebody who commands and of somebody who obeys. This is the pure political relation. From the point of view of an ontology, it is not that. There, Spinoza did not go along with Hobbes at all. The problem of an ontology is, consequently, according to this: being is said of everything that is, this is how to be free. I.e. how to exercise its power under the best conditions. And the state, even more the civil state, i.e. the entire society is thought like this: the ensemble of conditions under which man can exercise his power in the best way. Thus it is not at all a relation of obedience. Obedience will come, moreover, it will have to be justified by what it inscribes in a system where society can mean only one thing, namely the best means for man of exercising his power. Obedience is second compared to this requirement. In a philosophy of the One, obedience is obviously first, i.e. the political relation is the relation of obedience, it is not the relation of the exercise of power. We will find this problem again in Nietzsche: what is equal? What is equal is that each being, whatever it is, in every way exercises all that it can of its power, that, that makes all beings equal. But the powers are not equal. But each endeavours to persevere in its being, i.e. exercise its power. From this point of view, all beings are the same, they are all in being and being is equal. Being is also said of everything that is, but everything that is is not equal, i.e. does not have the same power. But being which is said of everything that is, that, that is equal. With that, it doesn't‚t prevent there being differences between beings. From the point of view of the difference between beings a whole idea of aristocracy can be established, namely there are the better ones. If I try to summarize, understand where we were the last time. We posed a very precise problem, the problem which I have dealt with until now, which is this: what is the status, not of Being [être], but of being [étant], i.e. what is the status of Œwhat is‚ from the point of view of an ontology. What is the status of the being [étant] or of what exists [existant] from the point of view of an ontology? I have tried to show that the two conceptions, that of the quantitative distinction between existing things, and the other point of view, that of the qualitative opposition between modes of existence, far from contradicting themselves, have been interlinked with one another the whole time. This finishes the first category: what is an ontology, and how is it distinguished from philosophies which are not ontologies. Second major category: what is the status of the being [étant] from the point of view of a pure ontology like Spinoza‚s? Inaudible intervention Gilles: You say that from the point of view of the hierarchy, what is first is difference and one goes from difference to identity. That is quite right, but I would just add: which type of difference is it about? Response: it is always finally a difference between Being [être] and something superior to being, since the hierarchy is going to be a difference in judgment. Therefore, judgment is done in the name of a superiority of the One over being. We can judge being precisely because there is an authority superior to being. Thus the hierarchy is inscribed as of this difference, since the hierarchy, even its foundation, is the transcendence of the One over being. And what you call difference is exactly this transcendence of the One over being. When you invoke Plato, difference is only first in Plato in a very precise sense, namely the One is more than being. Thus it is a hierarchical difference. Ontology goes from being [être] to beings [étants], i.e. it goes from the same, from what is, and only what is different, it goes therefore from being to the differences, it is not a hierarchical difference. All beings are also in Being. In the Middle Ages, there is a very important school, it was given the name the School of Chartres; and the School of Chartres, they depend mostly on Duns Scotus, and they insist enormously on the Latin term "equality.‰ Equal being. They say all the time that being is fundamentally equal. That doesn‚t mean that existing things, or beings [étants], are equal. But being is equal for all, which means, in a certain way, that all beings are in being. Consequently, whatever the difference you achieve, since there is a non-difference of being, and there are differences between beings, these differences will not be conceived in a hierarchical way. Or, they will be conceived in a hierarchical way very, very secondarily, to catch up with, to reconcile the things. But in the first intuition, the difference is not hierarchical. Whereas in philosophies of the One difference is fundamentally hierarchical. I would say much more: in ontology, the difference between beings is quantitative and qualitative at the same time. Quantitative difference of powers, qualitative difference of modes of existence, but it is not hierarchical. Then, of course, they often speak as if there had been a hierarchy, they will say that the reasonable man is better than the malicious one, but better in what sense and why? It is for reasons of power and exercise of power, not for reasons of hierarchy. I would like to pass to a third rubric which is connected at the second and which would come down to saying that if the Ethics - I defined as the two co-ordinates of the Ethics: the quantitative distinction from the point of view of power, the qualitative opposition from the point of view of the modes of existence. I tried to show last time how we passed perpetually from the one to the other. I would like to begin a third rubric, which is, from the point of view of the Ethics, how does the problem of evil arise. Because, once again, we have seen that this problem arose in an acute way, why? I remind you that I discussed the sense in which, from time immemorial, classical philosophy had set up this paradoxical proposition, by knowing very well that it was a paradox, namely evil is nothing. But precisely, evil is nothing, understand that there are at least two possible manners of speaking. These two manners are not reconciled at all. Because when I say evil is nothing, I could mean firstly one thing: evil is nothing because everything is Good. If I say everything is Good. If you write Good with a capital G, if you write it like that, you can comment on the formula word for word: there is being, good: The One is superior to being, and the superiority of the One over being makes being turn towards the One as being the Good. In other words, Œevil is nothing‚, means: inevitably evil is nothing since it is the Good superior to being which is the cause of being. In other words, the Good makes being. The Good is the One as the reason for being. The One is superior to being. Everything is Good means that it is the good that makes being what is. I am discussing Plato. You understand that Œevil is nothing‚ means that only the Good makes being, and correlatively: makes action. It was the argument of Plato: the malicious one is not voluntarily malicious since what the malicious one wants is the good, it is whatever good. I can thus say that evil is nothing, in the sense that only the Good makes being and makes action, therefore evil is nothing. In a pure Ontology, where there is no One superior to being, I say evil is nothing, there is no evil, there is being. Okay. But that engages me with something completely new, it is that if evil is nothing, then the good is nothing either. It is thus for completely opposite reasons that I can say in both cases that evil is nothing. In one case, I say that evil is nothing because only the Good makes being and makes action, in the other case, I say that evil is nothing because the Good is nothing too, because there is only being. Now we have seen that this negation of the good, like that of evil, did not prevent Spinoza from making an ethics. How is an ethics made if there is neither good nor evil. From the same formula, in the same era, if you take the formula: Œevil is nothing‚, signed by Leibniz, and signed by Spinoza, they both say the same formula, Œevil is nothing‚, but it has two opposite senses. In Leibniz it derives from Plato, and in Spinoza, who makes a pure ontology, it becomes complicated. Hence my problem: what is the status of evil from the point of view of ethics, i.e. from the whole status of beings, of existing things? We will return to the parts where ethics is really practical. We have an exceptional text of Spinoza: it is an exchange of eight letters, four each. A set of eight letters exchanged with a young man called Blyenberg. The sole object of this correspondence is evil. The young Blyenberg asks Spinoza to explain evil ? to be continued... The article is taken from: by Steven Craig Hickman There is no need to tell all over again how psychoanalysis culminates in a theory of culture that takes up again the age-old task of the ascetic ideal… – Anti-Oedipus, Gilles Deleuze & Felix Guattari Deleuze & Guattari will dissolve the mystery of the death instinct in Freud realizing that it gathered together the hidden threads in his secret narrative: the truth of Freud’s aspiration – to become a Priest, a Rabbi, a “director of bad conscience”.1 “If one looks for a reason why Freud erects a transcendent death instinct as a principle,” they tell us: “the reason will be found in Freud’s practice itself” (p. 333). After finding the abstract subjective essence of desire – the Libido, Freud forgot what he’d discovered and went looking for something else altogether. He sought some representational image of this abstract entity in the unconscious – his theatre of cruelty: what he found was Oedipus – the self-castrated, eyeless victim of castration and death. As Freud himself would tell it: The ascetic ideal is an artifice for the preservation of life … even when he wounds himself, this master of destruction, of self-destructing – the very wound itself compels him to live…” (p. 333). Freud would no longer see in desire a force of love in the world. No. Now desire must turn back against itself in the name of a horrible Ananke, the Ananke of the weak and the depressed, the contagious neurotic Ananke; desire must produce its shadow or its monkey, and find a strange artificial force for vegetating in the void, at the heart of its own lack (pp. 334-335). Deleuze and Guattari will question this deep wisdom of Freud’s anemic Ananke (Necessity) that binds desire in a weltering world of voidic cholera: “Is this really the right way to bring on better days? And aren’t all the destructions performed by schizoanalysis worth more than this psychoanalytical conservatory, aren’t they more a part of the affirmative task?” (p. 334) In fact they will see in this claustrophobic science of the mind, an Oedipal mind, a dark theatre of cruelty the habitation of ghosts and interior palaces where desire is brought to bare for its crimes, a sadistic chamber where Freud can observe the guilt of the past in all its terrible splendor. Instead of this dark cave Deleuze and Guattari will say, open the doors, let in a little fresh air and give us a “bit of a relation to the outside, a little real reality” (p. 334). Freud was the first to link death and war as he studied the aftermath of WWI; a linkage between psychoanalysis and capitalism in their twin engagement with death and war. (p. 335) “What we have tried to show apropos of capitalism is how it inherited much from a transcendent death-carrying agency, the despotic signifier, but also how it brought about this agency’s effusion in the full immanence of its own system: the full body, having become that of capital-money, suppresses the distinction between production and anti-production; everywhere it mixes anti-production with the productive forces in the immanent reproduction of its own always widened limits. The death enterprise (war) is one of the principle and specific forms of the absorption of surplus value in capitalism. (p. 335) What Freud discovers is that the death-instinct being immanent to the capitalist despotic signifier, the empty locus around which its system of absorption exists, that it must displace everything into this war-machine to block the schizophrenic escapes and place restraints on its flights. (p. 335) Capitalism is a war machine that binds desire within its own immanent logic as death: a negative desire that produces pure surplus-value out of the hell of its despotic and ascetic cult. It is at this point that they will introduce Zombie Capitalism: the “only modern myth is the myth of zombies – mortified schizos, good for work, brought back to reason” by the psychoanalytical priest of a new asceticism so that they can continue serving the war-machine like good subservient capitalists. (p. 335) It is the principle of death immanent to capitalism that produces the very limits that bind and impose a gap between social-production and desiring-production that keeps the zombies tied to the endless loop of a false desire for commodities and war. “Now this universe has as its function the splitting of the subjective essence into two functions, that of abstract labor alienated in private property that reproduces the ever wider limits, and that of abstract desire alienated in the privatized family that displaces the ever narrower internalized limits” (p. 337). In this system caught between abstract labor and desire the zombie citizen lives under a mortuary axiomatic: an axiomatic of simulacra, wherein the zombies cannibalize images instead of flesh: “death is not desires, but what is desired is dead” (p. 337) In truth, capitalism has nothing to co-opt; or rather, its powers of co-option coexist more often than not with what is to be co-opted, and even anticipate it. (p. 338) For those that remember Debord’s Society of the Spectacle all this will seem familiar. In Debord’s theory, media have become the quintessential tool of contemporary capitalism, and consumerism is its legitimating ideology. Or, to cite Debord’s famous quip, “the spectacle is capital accumulated to the point where it becomes image.”2 What is crucial about Debord’s theory is that it connects the state’s investment in social reproduction to its commitment to, “and control of, the field of images— the alternative world conjured up by the new battery of ‘perpetual emotion machines’ of which TV was the dim pioneer and which now beckons the citizen every waking minute.” Not only is the world of images a structural necessity for capitalism, it affirms the primacy of the pedagogical as a crucial element of the political. It enforces “the submission of more and more facets of human sociability— areas of everyday life, forms of recreation, patterns of speech, idioms of local solidarity . . . to the deadly solicitation (the lifeless bright sameness) of the market.” (Giroux KL 517-523) Under contemporary capitalism, state-sanctioned violence makes its mark through the prisons, courts, police surveillance, and other criminalizing forces; it also wages a form of symbolic warfare mediated by a regime of consumer-based images and staged events that narrow individual and social agency to the dictates of the marketplace, reducing the capacity for human aspirations and desires to needs embodied in the appearance of the commodity. In Debord’s terms, “the spectacle is the bad dream of modern society in chains, expressing nothing more than its wish for sleep.” (Giroux KL 526) What Debord would term the politics of consent is the acknowledgement that all aspects of social life are increasingly shaped by the communication technologies under the control of corporate forces. Of course this is even more so in our own time, when technologies of communication have become not only ubiquitous and invisible due to normalization, they actually replace reality with a surfeit of image, propaganda, and ideological constructs that seem to be more real than reality itself. As Giroux and Evans will affirm: Debord did not anticipate either the evolution of media along its current trajectories, with its multiple producers, distributors, and access, or the degree to which the forces of militarization would dominate all aspects of society, especially in the United States, where obsession with law enforcement, surveillance, and repression of dissent has at least equaled cultural emphasis on commercialization from 9/ 11 forward. The economic, political, and social safeguards of a past era, however limited, along with traditional spatial and temporal coordinates of experience, have been blown apart in the “second media age,” as the spectacularization of anxiety and fear and the increasing militarization of everyday life have become the principal cultural experiences shaping identities, values, and social relations. (Giroux KL 600-606) Following Deleuze and Guattari we should affirm both a destructive and constructive task incorporating schizoanalytical technics in becoming mechanics rather than a theatre director: the political and social unconscious is not an archaeology, there are no statues in this unconscious: there are “only stones to be sucked … and other machinic elements belonging to deterritorialized constellations” (p. 338). As they would tell us in “the unconscious it is not the lines of pressure that matter, but on the contrary the lines of escape” (p. 338). To seek out those constellations of resistance and revolt, those “lines of escape” and flight that will help us to open gaps and cracks in the current system of capitalism and its death machine, this is the task today. Against all representational theories that seek to interpret the socio-cultural, political, and economic unconscious we must realize that the very images that interpretation entails are the very tools of repression and death, the ascetic priests tools of choice that enslave and bind rather than uncover and liberate or emancipate the break-flows of desire. Instead of a cinematic or video game existence flicking by in synthetic-time frames, encapsulated in the violence of freeze-frame abstractions that present the surface textures of a symbolic existence caught in the imaginary of capital, an a-life of artificial extractions that confine flesh to a screen of repetition and loss rather than the break-flows of real time existence. This half-life in which we are bound to an interface existence, caught up in the flows of death machines that trap and bind us to a ghost-land of sound-scapes and images. “It is the very form of interpretation that shows itself to be incapable of attaining the unconscious, since it gives rise to the inevitable illusions … by means of which the conscious makes of the unconscious an image consonant with its wishes: we are still pious, psychoanalysis remains in the pre-critical age” (p. 339). We must break through this crystal palace dreamland of capital, discover lines of escape beyond its illusory fun house of gadgets and technological toys, else be entrapped forever in a void of commoditized identities, spinning in a self-voided paradise of Oedipal madness where we finally merge with our very machinic lives – our flesh dissolving in the war-machines that have now become our only reality. Ultimately the schizoanalytical technique unbinds the repressive Oedipal system of capital that has tied it to the death machines of production and zombie commodification, the compulsion to repeat an endless cycle of negative desire in a void of surplus-value profiting that sucks the life-blood out of the human waste expended and multiplied by this vast charnel house system. Instead of falling back into the trap of capitalist repression and re-Oedipalization, schizoanalysis “follows the lines of escape and the machinic indices all the way to the desiring-machines” (p. 339). Or, as they tell us: undoing the blockage or the coincidence on which the repression properly speaking relies; transforming the apparent opposition of repulsion … into a condition of real functioning; ensuring this functioning in the forms of attraction and attractive functioning, as well as enveloping the zero degree in the intensities produced; and thereby causing the desiring-machines to start up again. Such is the delicate and focal point that fills the function of transference in schizoanalysis – dispersing, schizophrenizing the perverse transference of psychoanalysis. (p. 339) For a social and political task one must take this and apply it to the repressive blockages within the capitalist system that keep the zombies bound and captivated to the simulacrum of image commodification and technologies of desire, providing an alternative to this death-machine zero sum world of capital; one that allows a transference from this illusory image-world of capital to a world where desiring-machines are no longer formed, mutilated, and bound to a negative desire situated in capital and its war-machines. We need a critical praxis that is not a reversion to pre-critical forms, but is worthy of the anti-representational critique developed by Deleuze & Guattari, one that seeks out in the functional blockages in the political, economic, and socio-cultural unconscious the part-objects that enforce its repressive stasis and violence of passivity and captures the desiring flows of surplus-joissance, all the while seeking lines of escape and flight out of this zombie globalist system of capital. Seeking cracks in the molecular fabric that encapsulates us in what that liberal-conservative Sloterdijk calls the “World Interior of Capital”; that illusionary ideological construct that is so pervasive and ubiquitous that it has become normalized to the point of invisibility, the Infosphere. 1. Anti-Oedipus Gilles Deleuze & Felix Guattari ( Penguin 2009) 2. Giroux, Henry A.; Evans, Brad (2015-06-22). Disposable Futures: The Seduction of Violence in the Age of Spectacle (City Lights Open Media) (Kindle Locations 515-517). City Lights Publishers. Kindle Edition. The article is taken from: Nietzsche’s accelerationist fragment in Deleuze and Guattari’s Anti-Oedipusby Obsolete Capitalism The strong of the futureDespite the passing of time there are fragments of thought that acquire a life of their own and hit the headlines of philo-sophical and cultural journals with regards to their evaluationand interpretation. Among the most famous ones is the Fragment on Machines by Karl Marx.1 More recently another «fragment» has gained importance in terms of discernment: a dark and forward looking «fragment in the fragment» by Friedrich Nietzsche nestled in one of Deleuze and Guattari’s Anti-Oedipus(1972) crucial pages.2 As widely known the reference to Nietzsche in the famous «accelerationist passage» in Deleuze and Guattari’s Anti-Oedipus is decisive and closes the paragraph entitled The Civilized Capitalist Machine (Chapter III, Par. 9, pp. 222-239). Until today the various commentators of such passage have left aside or overshadowed the specific reference to Friedrich Nietzsche’s Große Prozeß, others have simply quoted the «accelerate theprocess» issue referenced by Deleuze and Guattari, mention-ing Nietzsche’s book The Will of Power, but no one has everreferred to the precise fragment or its context and the poten-tial themes it implies. The quotation of the fragment is alwaysderived from critical essays or secondary literature books andnever from the original Nietzschean work, apart from a notein Wikipedia in the definition of the word «accelerationism»3 and Matteo Pasquinelli’s short mention in his English “post”called Code Surplus Value and the Augmented Intellect.4 It is likely that this omission finds its origin in the fact that Deleuze and Nietzsche’s English speaking/reading scholars, when referring to the English edition of the Kritische Gesa-mtausgabe edited by the Stanford University Press (Colli andMontinari critical edition), may not have all the posthumous fragments available. The collection The Complete Works of Friedrich Nietzsche in fact started in 1995 but the edition suddenlystopped after the publication of only three of the originallyproposed twenty volumes, due to the loss of one of the twocurators, Ernst Behler, who died in 1997. Only ten years later, in 2011 Alan D. Schrift and Duncan Large, the two newcurators, published three new volumes but the «accelerationist fragment» inserted in Vol.17 Unpublished Fragments: Summer 1886 – Fall 1887 will be presumably published later. The controversial final part of The Civilized Capitalist Machine may be fully and deeply understood only through a clearreference and analysis of the accelerationist process describedby Nietzsche. The specific identification of the above-men-tioned Nietzschean fragment which Deleuze and Guattari re-fer to, opens to a definitive interpretation of the final passage of The Civilized Capitalist Machine. Christian Kerslake, a sharpcritic and observer of Deleuze’s work finds the passage quite “difficult to comprehend”.5 Here is the famous passage whichhas become a crucial issue especially in the accelerationist area of commentators: “But which is the revolutionary path? Is there one?—To withdraw from the world market, as Samir Amin advises Third World countries to do, in a curious revival of the fascist “economic solution”? Or might it be to go in the opposite direction? To go still further, that is, in the movement of the market, of decoding and deterritorialization? For perhaps the flows are not yet deterritorialized enough, not decoded enough, from the view point a theory and a practice of a highly schizophrenic character. Not to withdraw from the process, but to go further, to “accelerate the process,” as Nietzsche put it: in this matter, the truth is that we haven’t seen anything yet.” 6 Our research has identified the precise Nietzschean fragment quoted by Deleuze and Guattari as shown above. It is a fragment positioned in two different Friedrich Nietzsche’s posthumous editions. The title of the fragment is The Strong of the Future and it was composed in the Fall of 1887. In the collection of fragments edited by Gast and Nietzsche’s sister (The Will of Power, 1906) 1.067 fragments were randomly listed and The Strong of the Future was numbered 898.7 This arbitrary collection of fragments entitled The Will of Power has produced controversial debates in both political and philosophical fields since the beginning of the twentieth century. The same fragment with the same title is present in Colliand Montinari’s The Complete Works of Friedrich Nietzsche. It may be found in Part II Vol. VIII of the Italian edition entitled Frammenti Postumi: 1887-1888 together with other 371 fragments that Nietzsche collected in a series provisionally entitled The Will of Power that he will never publish. Here the fragment is numbered (105) 9 [153]. In the original fragment, Nietzsche used the verb «beschle-unigen» - derived from the physics world - literary meaning «to accelerate something facilitating its faster track». In the English translation by Kaufmann in 1967 8 the verb has been rendered as «hasten» whereas «accelerate» would have probably been more pertinent even in English, due to the fact that the former deals with the necessity to accelerate (not only in a physical way), while the latter indicates an intrinsic increase of speed in a process. In the Italian translation the verb used is again «affrettare» (hasten) instead of «accelerare» (accelerate), strengthening the above-mentioned difference between the two verbs: «accelerare» means the intrinsic and physical increase of an event or of a process whereas «affrettare» shows an external provision of such increase. Actually the only significant commentator on Nietzsche’s fragment and Deleuze’s quotation is Pierre Klossowski9 in his Nietzsche and the Vicious Circle (1969), a work dedicated to Gilles Deleuze, who highly appreciated this publication together with Foucault. The useful fertility of Klossowski is dual, first on an exegetic side of his essay Nietzsche and the Vicious Circle and second for his «procreative» translations of Nietzsche’s works.Klossowski was a famous translator from German to Frenchfor the work of many intellectuals and philosophers like Ben- jamin, Wittgenstein, Heidegger (his Nietzsche 1971) and above all he proved to be the best interpreter of Nietzsche’s thoughtin France thanks to his masterful and superlative work on The Gay Science in 1954 but in particular for the translation of the Fragments posthumes - Autumn 1887 - mars 1888 edited by Galli-mard in 1976. The fragment we refer to, Les Forts de l’avenir, had already been released in Nietzsche et le Cercle vicieux in 1969. It is exactly there that we find the verb “beschleunigen” translated in«accélérer» (accelerate); therefore Klossowski’s interpretation has been at the basis of Deleuze’s choice in using the expression to accelerate the process when wondering which «revolutionary path» to undertake; that is the same question the accelerationist movement poses today. Through an exegetic analysis of the fragment The Strong ofthe Future in his Nietzsche and the Vicious Circle, Klossowski eval-uates Nietzsche’s thought (of 1887) very extant and contem-porary, able to move from untimely meditations to disconcertednewness in less than one hundred years, affirming that “the economic mechanism of exploitation (developed by science and the economy) is decomposed as an institutional structure into a set of means” entailing two results: “on the one hand, that society can no longer fashion its members as ‘instruments’ to its own ends, now that it has itself become the instrument of a mechanism; on the other hand that a‘surplus’ of forces, eliminated by the mechanism, are now made avail- able for the formation of a different human type: the strong of the future.10 To reach such a new type of man we should not obstruct this irreversible great process but foster its inexorably expansive acceleration in a mechanism which may seem (without being) contrary to the main aim of «the strong of the future»: the differentiation. The levelling and the social homogenization perpetrated by the democratization of the industrial society are responsible for men’s shrinking. The «strong» and the «lev-elled ones» will then act for or against such «inexorable law» in a paradoxical overturning, as well as workers and capitalists fight in favor or against the relentless law of the tendency of the rate of profit to fall, another big issue Deleuze and Guattari posed in the paragraph called The Civilized Capitalist Machine. We have now concluded this short essay whose aim was to precisely describe the Nietzschean source Deleuze and Guattari had drawn from in their famous passage of the «revolutionary path» in the book Anti-Oedipus and to produce theright bibliographic references to the «accelerationist» fragment in Nietzsche’s complex work. We are aware on the otherhand to have just outlined a challenging in progress work onthe decoding of the deepest meaning of the paragraph The Civilized Capitalist Machine and in particular of the accelera-tionist passage about the theory and the practice of decoded and deterritorialized flows. 1 Karl Marx: Grundrisse: Fragment on Machines - translated by Martin Nicolaus, Penguin,1973 2 Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari: Anti Oedipus. Capitalism and Schizophrenia, Universityof Minnesota Press, 1983 3 “Quoted in Strong, Tracy (1988). Friedrich Nietzsche and the Politics of Transfiguration.Berkeley: University of California Press. p. 211. Original in The Will to Power nr. 898”(accessed 18 August 2015) 4 Code Surplus Value and the Augmented Intellect, post/ late night notes del 10th March2014:http://matteopasquinelli.com/codesurplusvalue/ (accessed 23 August 2015). 5 Christian Kerslake Marxism and Money in Deleuze and Guattari’s “Capitalism and Schizofrenia” http://parrhesiajournal.org/parrhesia22/parrhesia22_kerslake.pdf 6 Deleuze-Guattari: Anti Oedipus. Capitalism and Schizophrenia, University of MinnesotaPress, p.239 7 Heinrich Köselitz(1854–1918), musician and actor, Friedrich Nietzsche’s friend whom henicknamed “Peter Gast”.Elisabeth Förster Nietzsche (1846 1935), Nietzsche’s sister who was often criticized by her brother, by Gast and by other Nietzschean followers/suppor-ters. She was a Nazi, pro-Arian and anti-Semite woman, responsible of Nietzsche’s philo-sophy manipulation. Hitler and all his general staff took part to her funeral in 1935. 8 Walter Kaufmann (1921-1980) was an American philosopher and Nietzsche’s scholar whotranslated The Will to Power (Random House, New York,, 1967 with R.J. Hollingdale). 9 Pierre Klossowski (1905-2001) was a French intellectual strongly influenced by Nietzsche’s works. He was an important translator, writer, philosopher, painter and one of the “spiri-tual father” of Deleuze and Guattari. 10 Pierre Klossowski: Nietzsche and the vicious circle The University of Chicago Press, 1997 -Chapter 6 “The vicious circle as a selective doctrine” p. 164. Bibliography Deleuze, G. e Guattari, F. (1983). Anti-OEdipus Capitalism and Schizophrenia Vol. I, Minneapolis, University of Minnesota Press. Deleuze, G. (1986).Nietzsche and Philosophie. London, Continuum. Heidegger, M. (1971). Nietzsche,translated by Klossowski P., Paris, Gallimard. Kerslake, C. (2015). Marxism and Money in Deleuze and Guattari’s Parrhesia (22). pp 38 - 78. Online article: http://www.parrhesiajournal.org/parrhesia22/parrhesia22_kerslake.pdf Klossowski, P. (1997). Nietzsche and the vicious circle - translated by Daniel W.Smith, Chicago,The University of Chicago Press Marx, K. (1973).Grundrisse: Fragment on Machines- translated by MartinNicolaus, New York, Penguin. Nietzsche, F. (1906). Der Wille zur Macht. (eds.)Förster-Nietzsche, E. eGast P.,Weimar: Nietzsche-Archiv. Nietzsche, F. (1976). Fragments posthumes, Autumn 1887- mars 1888 . Paris, Gallimard. Nietzsche, F. Opere (1961-2014), Frammenti postumi 1887-1888, Volume VI,tomo 2, trad. F.Masini, edizione critica a cura di Colli e Montinari, Milano, Adelphi. Nietzsche, F. (1987).The Genealogy of Morals , New York, Boni andLivingstone. Nietzsche, F. (1967).The Will to Power. (eds.) Kaufmann W., Hollingdale R.J., New York, Random House. Nietzsche, F. (1947/1948). La Volonté de Puissance. (eds.) Würzbach, F.,Paris, Gallimard. Nietzsche, F. (1967). Le Gai Savoir : Fragments posthumes, été 1881 - été1882. Paris, Gallimard Nietzsche, F. (1980). Nachgelassene Fragmente 1885-1889. [Die Starken derZukunft. pp. 424-425]. Samtliche Werke, Kritische Studienausgabe. Band12. 1.Teil:1885-1887. Munich, De Gruyter. Nietzsche, F. (1995 -- ). The Complete Works of Friedrich Nietzsche. Redwood City, Stanford University Press. Pasquinelli, M. (2014). Code Surplus Value and the Augmented Intellec, post/late night notes http://matteopasquinelli.com/code-surplus-value/ Strong, T. (1988). Friedrich Nietzsche and the Politics of Transfiguration. Berkeley, University of California Press. The essay is taken from: by Steven Craig Hickman Speaking with the dead can be so instructive. They remember what the living have forgotten, or would not know if they could. The true frailty of things. .-Thomas Ligotti, Grimscribe In Thomas Ligotti’s The Mystics of Muelenberg we’re presented as usual with a world which is askew, tipped in favor of the strange and deformed, the grotesque and macabre rather than the glittering façade of some Platonic realm of the marvelous: If things are not what they seem—and we are forever reminded that this is the case—then it must also be observed that enough of us ignore this truth to keep the world from collapsing. Though never exact, always shifting somewhat, the proportion is crucial. For a certain number of minds are fated to depart for realms of delusion, as if in accordance with some hideous timetable, and many will never be returning to us. Even among those who remain, how difficult it can be to hold the focus sharp, to keep the picture of the world from fading, from blurring in selected zones and, on occasion, from sustaining epic deformations over the entire visible scene.1 From time to time I like to reread these demented stories of a mind that has suffered the bitter sweetness of its own forgotten wisdom. The notion that the world that most of us behold is held together by a secret group of individuals scattered across time, a forbidden sect that has been stamped with the task of binding the hellish deformations of reality and containing its force is strangely disquieting. That this dark brotherhood of the mad and insane, the eccentric and oddball are our only hope against the powers of hyperchaos, the Keepers of the Great Art, those who balance the thin red line between reality and the unreal and weave the invisible threads that ubiquitously connect us all in a timeless world of illusion is a truth that if accepted would in itself drive us all insane. So that the troubadours, jongleurs, tricksters, and mad shamans who wander the broken boundaries of existence and keep us safe, while they move in two worlds at once: split between the real and unreal, brokering the lines of flight that bind and unbind reality. They are the mad ones who defend us against the insane truth, who channel the secrets of existence in parables and allegories, while living out in their own lives and minds the inevitable corruption that would destroy the rest of us. One can imagine that from time to time one of our benefactors succumbs to the power of the other side, is lured and tempted to give into the secret force of its entrapments. This forces us to think about our own part in this madness and how we are ourselves corrupted and corrupting in our very inability to separate the real and unreal in our lives. What if one were to wander into one of those abandoned zones, a zone of exclusion and corruption, move in the world where reality was unprotected, where the balance had suddenly shifted exposing the truth behind the curtain of lies; where appearance as appearance gave up its artificial semblance and exposed the underlying nullity, the dark abyss of nothingness and formlessness? What if one saw behind the phenomenal and into the noumenon and discovered that it was a hyperchaotic sea of time without sense or reason? What if the hyperchaos that surrounds us suddenly presented itself without illusion, opened its dark powers to you vision: what would you do? What could you do? There are those such as Lacan and Zizek who suggest that the saving grace is that we have an inbuilt gap or split, that keeps us bound in a subjective transcendence of illusory fictions. That the sea of appearances and phenomena around us are all that we will ever have direct access too. That our brains, our minds are shaped by rules of language and logic that enforce the barriers against the truth of the Real for our protection. That if we were to know reality as it is we would all go mad. Yet, others have boldly suggested that this too is a lie, a fiction: that in truth the world that we believe is real is itself the great fiction, the lie upon which we have obliterated the real world and replaced it with a hyperreality so real that we are now lost in an abyss of our own making. Will we find our way out of this labyrinth? Where is Ariadne’s thread to guide us back to the formless sea of unbeing? In the old Gnostic mythologies the Archons (kelippot, dark vessels) were the Watchers who keep us locked away in Time’s Prison. What if the reverse were true? What if in fact they are our secret defenders? What if they were the secret or hidden, occult brotherhood who have all these eons protected us from ourselves? What if what we should fear is our own powers? What if in fact we were the dark gods who have forgotten our own powers, and the gatekeepers were put in place by us to protect us from our terrible deeds, our own horrendous past? What if we are the destroyers against which we have built up such dark mythologies, and that if we ever tore down the barriers between our world and the Real we would discover the terrible truth of our own dark secret? That the evil we project upon darkness is the face of our own abysmal nature? What then? Maybe Time is a Prison we built against our own terrible existence, and that the only thing between us and oblivion is the gates of illusion. Would you still storm the gates if you knew this to be the truth? In the old mythologies of kabbalism is the notion of restitution (“Tikkun ha-Olam“), or the ‘lifting of the sparks’ (Netzotzim) – the notion that throughout time a slow and methodical metempsychosis of the original sparks of light that broke away from the dying embers of a Dead God as he died during the cataclysmic catastrophe that gave birth to our Universe would one day be restored and brought together in an infinite Body of Light, the Adam Kadmon of Living Fire at the End of Time. What if the opposite were true, what if what we are seeking is not a restitution but the annihilation of the sparks, a dark gnosis in which each of us slowly awakens to our own suicidal glory of annihilating the light of which we are shadows and embers of a darker realm of seething energy? What if instead of total restitution there is a total unmaking and unbinding of the Light into utter darkness and hyperchaos? That Time will end only when the last of the sparks is annihilated in this ocean of the abyss? We know that our universe of stars, dust, and light is but a minimal dance upon a ocean of dark matter and energy, that in truth what we call the universe is but a small fraction of this colder dimension, a truth that we cannot quantify nor know but infer from the instruments of our sciences and mathematical theorems. As Ligotti in his tale will say: For no one else recalls the hysteria that prevailed when the stars and the moon dimmed into blackness. Nor can they summon the least memory of when the artificial illumination of this earth turned weak and lurid, and all the shapes we once knew contorted into nightmares and nonsense. And finally how the blackness grew viscous, enveloping what light remained and drawing us into itself. How many such horrors await in that blackness to be restored to the legions of the dead. CHORAMANCY: A USER’S GUIDECame across an interesting essay in Mind Factory yesterday in which a consulting group was hired by the City of Miami because it had a “image” problem. People were perceiving Miami as deadly and crime ridden, a place where terror lurked in the sun and shadows everywhere. So the Florida Research Ensemble (FRE) developed a prototype for an inventional consulting practice, tested in the city of Miami, Florida.1 The notion that one could hire a consulting practice to invent reality struck my humor button, till I began thinking about Ligotti’s tale. This notion that people could invent an image, align the appearances of reality in such a way that the public at large might suddenly be lured to believe that a City that only yesterday was seen as a terrifying and hideous nightmare world of crime could become a sunny and happy world full of light and gaiety struck me odd. For FRE the problem was simple: it was a public relations crisis of the first order: the damage done to the image of Florida by the murder of a number of tourists had caused their client untold revenue and tourist dollars to be lossed in the past few years to a perceived reality. What was needed was to change this perception, to invent a new perceived image of reality to replace this bad economic image that had caused their client to lose revenue. As part of the image crisis management FRE was set a task to create a “Fifth Estate”: develop a practice for the internet that allows netizens to become agents of a “fifth estate,” giving citizens a voice in the public policy process equivalent at least to that of journalism…(KL 3291) What they discovered is that our of 41 million visitors over a 14 month period that nine tourists had been killed (3.2% of Miami’s murders). As one official said: “We have a huge perception problem, but nonetheless a real problem.” What transpired after bad publicity from news outlets is that the Commerce Secretary suspended tourist advertising temporarily, while countering negative news coverage. In the tourism business, he said, image is the business and has a direct bearing on the health of the industry. (KL 3318) Between News, Noir and Hard-boiled fiction, huckster propaganda (to sell real estate off-shore), Haitian and Cuban boat immigrants, etc. the city was caught in a continuous oscillation between two competing narratives, that of “Magic City” and “Paradise Lost.”(KL 3441) The works of Elmore Leonard and Charles Willeford, and in the Television series Miami Vice had over the years contributed to tourist imagery of the noir and crime element fears as well. As they discovered: Sheila Croucher, in Imagining Miami, summed up the issue: “Miami is a city without true substance, a state of mind instead of a state of being.”[ 168] As James Donald observed, every city is a state of mind that owe as much to discourse as to people and place. “ [The imagined city] has been learned as much from novels, pictures and half-remembered films as from diligent walks round the capital cities of Europe. It embodies perspectives, images, and narratives that migrate across popular fiction, modernist aesthetics, the sociology of urban culture, and techniques for acting on the city.” (KL 3459) Over the years news, advertising , noir fiction had all contributed to the invention of Miami’s image as a crime infested world that had slowly accrued into peoples (tourists) minds and dissuaded them from viewing this city as a travel destination. So FRE realized that if every city is a state of mind then they’d need to change the image of the city to create an atmosphere, a feeling, an ambiance more congenial to tourist travel. As they discovered they’d need to participate in genre building and reformulate the city from the formulaic mode of Miami Vice to one of Miami Virtue. One aspect of this was the notion of theoria: The discourse of the sages of the ancient theoria that we had adopted as a relay for the new consultancy expressed the state of mind known as “ataraxy,” a kind of serene indifference to the accidents and tribulations of the external world. (KL 3516) To build a new image of the city they started with a notion of psychogeography: the mapping of the city as an allegorical story that could be mapped to a tourist cognitive vision of the world. The relevance of mystory as a basis for testimonial is that it is a holistic practice, designed originally as a way to compose simultaneously in four (more or less) discourses. What one testifies to in the first place is the inventory of identifications or quilting points constituting one’s feeling of being a unified “self.” Mystory is a cognitive map of its maker’s psychogeography. The popcycle that I worked out in Heuretics remotivates an allegorical quaternary. The four levels of allegory serve as the four elements (Earth, Air, Fire, and Water) into which Plato’s chora sorted chaos. (KL 3664) I want go into the details which are lengthy and go into the background of allegorical terminology, etc. Needless to say they updated the older forms of allegorical systems with current scientific and philosophical models. Ultimately they narrowed their focus to one specific zone: the Miami River. Here the Haitian population lived amid the ruins of old ships, buildings, and make-shift housing projects. The group began to weave the history, mythologies, stories, and milieu of their culture into the tourist image the City could shape to a new image that would allow both the Haitian population and city to benefit from each others cultural mix through an allegorical exchange of images. They were able to accomplish this through a mixture of photography, story, advertisement, fiction, and other intermediation that allowed the perceived threat of the alien other (“alterity”, “aporia”) to be brought from the Outside in in such a way as to open an exchange between the various elements of both cultures that had been wary of each other. As they realized following the work of Michael Serres the tourist situation, like every other intersubjective experience, must take into account as least three positions: host, guest, “parasite”. (KL 4170) This allowed them to shape a policy that had once been based on exclusionary practices to become one on inclusion: Applied to the policy question of the Caribbean Code, this formula proposes the suspension of the interdiction and boarding of Haitian vessels by the Coast Guard, to be replaced with the “boarding” of Haitians at city expense: “learn about boarding from boarding.” (KL 4174) The politics of the stranger, in contrast, puts the interests of the other first, without expectation of reciprocity. It remains to be seen what sort of policy might be entailed by the aporia of hospitality, but its impossibility in principle is nearly the inverse of Prisoner’s Dilemma. “For unconditional hospitality to take place you have to accept the risk of the other coming and destroying the place, initiating a revolution, stealing everything, or killing everyone. That is the risk of pure hospitality and pure gift.” Pure gift, in other words, constitutes the impossible necessity of ethics unbounded by the external authority of some Master Signifier (God, King, etc.). (KL 4189) ASHES AND PUTTY“I once knew a man who claimed that, overnight, all the solid shapes of existence had been replaced by cheap substitutes: trees made of poster board, houses built of colored foam, whole landscapes composed of hair-clippings. His own flesh, he said, was now just so much putty. Needless to add, this acquaintance had deserted the cause of appearances and could no longer be depended on to stick to the common story. Alone he had wandered into a tale of another sort altogether; for him, all things now participated in this nightmare of nonsense. But although his revelations conflicted with the lesser forms of truth, nonetheless he did live in the light of a greater truth: that all is unreal. Within him this knowledge was vividly present down to his very bones, which had been newly simulated by a compound of mud and dust and ashes.” (Ligotti, KL 1529) This notion that reality is malleable, that we can reinvent realities for tourists or allow ourselves to follow our own tendencies into the unreal worlds around us is part and partial of the current state of theoria. That a city we perceived as dark and shadowy only yesterday could suddenly manifest itself as a magic kingdom or vice versa as a nightmare world of inordinate monstrosity is to know that reality is no longer a solid fixed substance, that form is a floating signifier both material and immaterial and unbounded. That nothing is real, that everything might take on the hues of unreality and metamorphosis, and that change might just find you in the nightmare of nonsense and strangeness is par for the course in a world where things are not what they seem. As Ligotti’s narrator states it: “In my own case, I must confess that the myth of a natural universe—that is, one that adheres to certain continuities whether we wish them or not—was losing its grip on me and gradually being supplanted by a hallucinatory view of creation. Forms, having nothing to offer except a mere suggestion of firmness, declined in importance; fantasy, that misty domain of pure meaning, gained in power and influence.” (Ligotti, KL 1534) If as many materialists from Giordano Bruno to Bataille and in our own time Nick Land have attested: matter is formless and energetic, and our so called reality is but a mask for the greater unreality or surreality of the immanent darkness that our own brain distorts and deforms. We may live in a world that could change at any moment into something else: is this horror or comforting? The collapse of the real into the unreal might be an excessive joy for some, and for others a corruption beyond all belief. Hell or paradise: isn’t this in the eye of the beholder? As William Blake once hoped, what we need is a marriage of heaven and hell: “Energy is Eternal Delight.” As the narrator describes the thoughts of Klaus Klingman: “I am a lucky one, parasite of chaos, maggot of vice. Where I live is all nightmare, thus a certain nonchalance. I am accustomed to drifting in the delirium of history.” (KL 1562) Klingman who is neither a protector nor a defender against the ancient curse of corruption, a man who simply drifts between the gaps like an alien priest of some insubordinate sect. A man who knew the truth but had bypassed its message for a more serene terror. He’d become the witness to the slow decay, the coming disintegration of things. Mulenberg, the center of the vast abject triumph of the nameless fruit: “Throughout the town, all places and things bore evidence to striking revisions in the base realm of matter: precisely sculptured stone began to loosen and lump, an abandoned cart melded with the sucking mud of the street, and objects in desolate rooms lost themselves in the surfaces they pressed upon, making metal tongs mix with brick hearth, prismatic jewels with lavish velvet, a corpse with the wood of its coffin.” (KL 1609) As Bataille would say existence “no longer resembles a neatly defined itinerary from one practical sign to another, but a sickly incandescence, a durable orgasm” (p. 82).3 The lonely brotherhood that had for so long held back the corruption of the universal decay had abandoned the city leaving the people to fall before the bleak misery of things: “All were carried off in the great torrent of their dreams, all spinning in that grayish whirlpool of indefinite twilight, all churning and in the end merging into utter blackness.” (KL 1614) Like the Pleroma of the ancient gnositcs the people were in the place of the dark light without knowing it, the place where time, memory, and thought were forgotten in the silence of night and chaos. As Klingman will tell the young narrator: I am one with the dead of Muelenburg . . . and with all who have known the great dream in all its true liquescence. (KL 1624) As if enacting a parody of the Great Art, the alchemical ceremony of fire, Klingman anoints the narrator who is seeking to know the truth of the ancient world to which Mulenberg has succumb: “To cure you of doubt, you first had to be made a doubter. Until now, pardon my saying so, you have shown no talent in that direction. You believed every wild thing that came along, provided it had the least evidence whatever. Unparalleled credulity. But tonight you have doubted and thus you are ready to be cured of this doubt.” (KL 1627) Doubting the murderousness of existence is the first step into oblivion. As Klingman in a moment of dark clarity tells the young initiate: “This is my gift to you. This will be your enlightenment. For the time is right again for the return of fluidity, and for the world’s grip to go slack. And later so much will have to be washed away, assuming a renascence of things. Fluidity, always fluidity.” (KL 1631) Maybe this is all we can expect now in our world, a slow withdrawal into that cold night of time without Time, a measured movement into the liquidity of things where life will be washed in the blood of Death without appeal. For too long we have held on to the myth of solidity, fixed the world into static objects; left the movement of the shadows fall before our inner gaze. We’ve lived in the sun too long, let the daylight shape our lives and thoughts. Now is the time of Night and Chaos. All hope of those of the dark sect gone back down into the dark folds of the immaterial material of the universe, where energy and light, the intransigent envelope of nothingness dissolves in a recourse to everything that compromises the powers that be in matters of form, ridiculing the traditional entities, naively rivalling stupefying scarecrows. (Bataille, p. 51) The Great Unraveling has begun, the slow and methodical decomposition of all things into the darkness. We who once believed in the myth of light have found the power of darkness to hold the pure energy, that active principle of matter: eros and thanatos, twins of the dark path call to us at the crossroads of time and the pure instant. Where we find the hanged one upside down in the place of the headless delirium of the Pleroma we will at last discover the impossible shape of Time.

The Antarctica is taken from:

CHAPTER 1