|

by Steven Craig Hickman

loading...

In one of Benjamin’s journal entries we hear him describe Brecht, saying,

For several years they have been subsumed, now under one key concept, now under another, so that non-Aristotelian logic, behaviourist theory, the new encyclopedia and the critique of ideas have, in turn, stood at the centre of his preoccupations. At present these various pursuits are converging upon the idea of a philosophical didactic poem. (Here “they” is: “the thoughts which occurred to him within the scope of epic theatre”)

Benjamin: Whilst becoming more closely concerned with the problems and methods of the proletarian class struggle, he has increasingly doubted the satirical and especially the ironic attitude as such. But to confuse these doubts, which are mostly of a practical nature, with other, more profound ones would be to misunderstand them. The doubts at a deeper level concern the artistic and playful element in art, and above all those elements which, partially and occasionally, make art refractory to reason. Badiou: For Brecht, art produces no truth, but is instead an elucidation – based on the supposition that the true exists – of the conditions for a courage of truth (p. 6, Inaestheticism)

This sense of having the courage of truth, of elucidating the conditions and milieu within which a truth arises in time in dramatic tension is at the heart of his play on Galileo. Truths are not situated in some Platonic mirror land beyond, but arise immanently in time through appearance as appearance (i.e., they are dialectic and have a history, temporal and formidable, concrete universal truth rather than some absolute situated beyond time or timeless). Between an epic and didactic drama and poetry Brecht tried to resolve tensions within his vision. Whether he succeeded or not is worthy of study, for it is this combination of the materialist dialectic applied to artistic creation and splendor that allowed him to educe and educate a generation into a vision at once egalitarian and bent on building a life worth living on our planet.

As Benjamin would note:

Brecht’s heroic efforts to legitimize art vis-à-vis reason have again and again referred him to the parable in which artistic mastery is proved by the fact that, in the end, all the artistic elements of a work cancel each other out. And it is precisely these efforts, connected with this parable, which are at present coming out in a more radical form in the idea of the didactic poem. In the course of the conversation I tried to explain to Brecht that such a poem would not have to seek approval from a bourgeois public but from a proletarian one, which, presumably, would find its criteria less in Brecht’s earlier, partly bourgeois-oriented work than in the dogmatic and theoretical content of the didactic poem itself. ‘If this didactic poem succeeds in enlisting the authority of marxism on its behalf,’ I told him, ‘then your earlier work is not likely to weaken that authority.’ (1934—27 September Dragør)

I believe that it is just here in this return to the epic form, at once parable and didactic, that a new art needs to emerge in our own time. For too long we’ve been under the tutelage of those like Harold Bloom who enforce a ever deepening turn inward in a now defunct romanticism that seems to have ended in such poets as John Ashbery under the auspices of twilight and evening land belatedness. Instead of this nihilism we need a return to other modes of being and artistic excellence. Brecht is one of those lights, one that stood for the proletariat against the elite purveyors of an art of sycophancy. An alliance of poetry, drama, and philosophy once again might emerge in dialogue and partnership in our age.

We’ve known for years that the playful ironizing of postmodern thought led into a quagmire of an ultra-nihilism from which there was to be no return, but rather the duplicitous involutions of a play-of-(intra)textuallity without end; a no man’s land of blindness and insight; a world where the knots of mind and text collaborated to turn humans away from reality into the cesspool of the imaginary. Now its time to resolve this chimera into the fantastic beast it always was: a philosophy of zero, of apathy and depressive realism; a world of democratic liberal materialism that has failed us utterly. What Badiou, Zizek, and other materialist dialectics offer is the truth between bodies and languages, an epic vision that can educate us once again into the environs of our own truths. We’re all in this together, but time to put off the blindfolds, take off the gloves and fight for something worthy of what remains human and alive.

taken from:

loading...

0 Comments

Hear Antonin Artaud’s Censored, Never-Aired Radio Play: To Have Done With The Judgment of God (1947)11/21/2017

loading...

Antonin Artaud had his first mental breakdown at the age of 16 and, from there on out, spent much of his life in and out of asylums. Diagnosed with “incurable paranoid delirium,” Artaud suffered from hallucinations, glossolalia, and bouts of violent rage. And his treatment probably did about as much harm as it did good. He was prescribed laudanum, which gave him a lifelong addiction to opiates. He endured some truly horrific procedures like electric shock treatment along with the highly dubious insulin therapy, which put him in a coma for a while.

In spite of this, Artaud proved to be a hugely influential theorist and playwright, famous for coining the term, “Theater of Cruelty.” His performances were designed to assault the senses and sensibilities of the audience and awaken them to the base realities of life -- sex, torture, murder and bodily fluids. Artaud wanted to break down the boundary between actor and audience and create an event that was ecstatic, uncontained and even dangerous. His ideas revolutionized the stage. As the late great Susan Sontag once wrote, “no one who works in the theater now is untouched by the impact of Artaud’s specific ideas.”

But generally speaking, his ideas about theater were more popular than his actual productions. One of his most famous plays, first staged in 1935, was Les Cenci, about a father who rapes his daughter and then gets brutally killed by his daughter’s hired thugs. The play was a flop when it debuted, running for a mere 17 performances. Even Sontag conceded that Les Cenci was “not a very good play.”

Artaud’s last work was an audio piece called To Have Done With The Judgment Of God (Pour en Finir avec le Jugement de dieu), and it proved to be equally unpopular, at least with some very important people. Commissioned by Ferdinand Pouey, head of the dramatic and literary broadcasts for French Radio in 1947, the work was written by Artaud after he spent the better part of WWII interned in an asylum where he endured the worst of his treatment. The piece is as raw and emotionally naked as you might expect –an anguished rant against society. A raving screed filled with scatological imagery, screams, nonsense words, anti-American invectives and anti-Catholic pronouncements.

loading...

The piece (above) was slated to air on January 2, 1948 but station director Vladimir Porché yanked it at the last moment. Apparently, he wasn’t terribly fond of the copious references to poop and semen nor the anti-American vitriol. Porché’s rejection caused a cause célèbre among Parisian intellectuals. René Clair, Jean Cocteau and Paul Éluard among others loudly protested the decision, and Pouey even resigned from his job in protest, but to no avail. It never aired. Artaud, who reportedly took the rejection very personally, died a month later. You can listen to the broadcast above. And, in case your French isn’t up to snuff, you can still appreciate its theatrical elements, maybe while reading an English translation of the radio play script here.

If you can't get enough of Artaud's final work, you can watch this staged version of To Have Done With the Judgment of God below starring Billy Barnum and John Voigt (no, not Angelina Jolie's father, the avant-garde musician).

taken from:

2014 | Russia | Documentary | 27 min.

Director: Irina Bessarabova, Igor Volosetsky

loading...

In the film of the producer center of the studio. M. Gorky modern theater directors reflect on the relevance of the Stanislavski system. For example, Dmitry Volkostrelov is convinced that Konstantin Sergeyevich expanded the boundaries of the theater and therefore it is important to study the system in order to understand the actor's nature. Roman Viktyuk at the rehearsals of the performance "Don Juan" speaks of Stanislavsky's system as a method that tunes the actor to the ability to throw energy into space. Adolf Shapiro believes that "it is possible that some provisions are already outdated, but the actor who owns the method, quickly learns other systems." Dmitry Krymov rehearsing the play "Katya, Sonya, Polya, Galya, Vera, Olya, Tanya ..." says that it is interesting for him to work in mixing different systems, but Stanislavsky's system is the basis of the theater: "It's like building a , Owning a sopromate, you can build something incredible, like Gaudi, and you can and "Khrushchev."

Vladimir Mirzoyev believes that "a separate director is a separate school," and Andrei Zhitinkin shares his experience in the US: "Stanislavsky is already a brand ...". Summarizes all the theatrical the Inna Solovyov said: "... Stanislavsky's system is a variety of ways to communicate with the public, with the role, with partners, with the surrounding world ...".

loading...

The authors also used archival footage of rehearsals by Konstantin Sergeyevich Stanislavsky.

loading...

No actor, no play, no theatre in this century has remained untouched by the influence of Constantin Stanislavsky-actor, director, founder of the Moscow Art Theatre of modern acting. His look for reality in character depiction and his well known stagings of now-exemplary plays are followed utilizing documented film, period photos, his directorial scratch pad and sensational scenes from Moscow Art Theater preparations. Demonstrates the advancement of Stanislavsky's celebrated strategy for "truth in art." Shows with the actors in his organization and talking about the mental prerequisites of a portrayal with one of his on-screen characters - how to display the life in front of an audience.

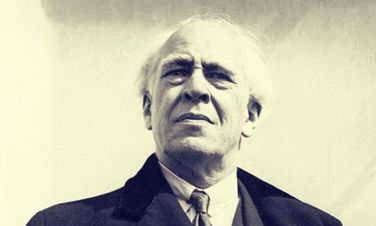

Born in 1863 in Moscow, Russia, Constantin Stanislavski began working in theater as a teenager, going ahead to end up noticeably an acclaimed actor and chief of stage creations. He helped to establish the Moscow Art Theater in 1897 and built up an execution procedure known as strategy acting, permitting performing artists to utilize their own histories to express true feeling and make rich characters. Ceaselessly sharpening his hypotheses all through his profession, he died in Moscow in 1938.

Constantin Stanislavski was born Konstantin Sergeyevich Alekseyev in Moscow, Russia, in January 1863. (Sources offer changing data on the correct day of his introduction to the world.) He was a part of a wealthy clan who adored theater: His maternal grandma was a French on-screen character and his dad constructed a stage on the family's estate.

Alekseyev began acting at 14 years old, joining the family dramatization circle. He built up his dramatic aptitudes significantly after some time, performing with other acting gatherings while working in his tribe's assembling business. In 1885, he gave himself the stage moniker of Stanislavski—the name of a kindred performer he'd met. He wedded instructor Maria Perevoshchikova three years after the fact, and she would join her significant other in the genuine review and quest for acting.

Opening the Moscow Art Theatre

In 1888, Stanislavski established the Society of Art and Literature, with which he performed and coordinated preparations for right around 10 years. At that point, in June 1897, he and dramatist/chief Vladimir Nemirovich-Danchenko chose to open the Moscow Art Theater, which would be an other option to standard the theatrical aesthetics of the day.

The organisation opened in October 1898 with Tsar Fyodor Ivanovich by Aleksey K. Tolstoy. The theatre's consequent creation of The Seagull was a historic point accomplishment and reignited the vocation of its essayist Anton Chekhov, who went ahead to make plays particularly for the organisation.

Over the next decades, the Moscow Art Theater built up a stellar residential and global notoriety with works like The Petty Bourgeois, An Enemy of the People and The Blue Bird. Stanislavski co-coordinated preparations with Nemirovich-Danchenko and had conspicuous parts in a few works, including The Cherry Orchard and The Lower Depth.

In 1910, Stanislavski took a holiday and flew out to Italy, where he concentrated the exhibitions of Eleanora Duse and Tommaso Salvini. Their specific style of execution, which felt free and naturalistic in contrast with Stanislavski's impression of his own endeavors, would incredibly motivate his speculations on acting. In 1912, Stanislavski made First Studio, which filled in as a preparation ground for youthful performers. After 10 years, he coordinated Eugene Onegin, a musical show by Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky.

'Stanislavski Method'

Amid the Moscow Art Theater's initial years, Stanislavski took a shot at giving a directing structure to on-screen characters to reliably accomplish profound, significant and restrained exhibitions. He believed actors needed to inhabit authentic emotion while on stage and, to do so, they could draw upon feelings they'd experienced in their own lives. Stanislavski likewise created practices that encouraged actors to explore character motivations, giving exhibitions profundity and an unassuming authenticity while as yet focusing on the parameters of the production. This strategy would come to be known as the "Stanislavski method" or "the Method."

Later Years and Legacy

The Moscow Art Theater attempted a world visit in the vicinity of 1922 and 1924; the organization headed out to different parts of Europe and the United States. Several members from the theater chose to remain in the United States after the visit was over, and would go ahead to educate entertainers that included Lee Strasberg and Stella Adler. These performers thusly shaped the Group Theater, which would later prompt the making of the Actors Studio. Strategy acting turned into a very persuasive, revolutionary technique in theatrical and Hollywood communities group amid the mid-twentieth century, as confirm with actors like Marlon Brando and Maureen Stapleton.

After the 1917 Russian Revolution, Stanislavski confronted some feedback for not delivering socialist works, yet he could keep up his organization's one of a kind point of view and not battle with a forced masterful vision. Amid an execution to recognize the Moscow Art Theater's 30th anniversary, Stanislavski endured a heart attack.

Stanislavski spent his later years focusing on his writing, directing and teaching. He died on August 7, 1938, in the city of his birth.

loading...

Editorial Staff

loading...

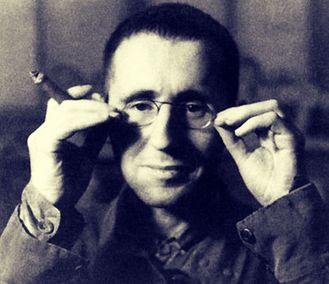

Bertolt Brecht was one of the most influential playwrights of the 20th century. His works include The Threepenny Opera (1928) with composer Kurt Weill, Mother Courage and Her Children (1941), The Good Person of Szechwan (1943), and The Resistible Rise of Arturo Ui (1958).

Brecht was born in Augsburg, Bavaria, in 1898, and the two world wars straightforwardly influenced his life and works. He wrote poetry when he was a student but studied medicine at the Ludwig Maximilian University of Munich. After military service during World War I, he abandoned his medical studies to pursue writing and the theater.

A member of the Independent Social Democratic Party, Brecht wrote theater criticism for a Socialist daily paper from 1919 to 1921. His plays were restricted in Germany in the 1930s, and in 1933, he went into outcast, first in Denmark and after that Finland. He moved to Santa Monica, California, in 1941, planning to write for Hollywood, yet he drew the consideration of the House Un-American Activities Committee. Despite the fact that he figured out how to redirect allegations of being a Communist, he moved to Switzerland after the hearings. He migrated to East Berlin in 1949 and ran the Berliner Ensemble, a theater organization. As an director, he pushed the "alienation effect" in acting—an approach expected to keep the crowd candidly uninvolved in the predicaments of the characters.

Brecht's verse is gathered in Poems 1913-1956 (1997) and Poetry and Prose: Bertolt Brecht (2003). He composed a wide assortment of verse, including periodic ballads, sonnets he set to music and performed, songs and poems for his plays, personal poems recording tales and considerations, and political sonnets. Writer Michael Hofmann, in "Singing About the Dark Times: The Poetry of Bertolt Brecht" for the Liberal, remarked, “In the course of a mobile, active and engaged life, the poems were the intelligent, compressed, adaptable and self-contained form for both his private and his public address.”

Brecht was influenced by a wide variety of sources including Chinese, Japanese, and Indian theatre, the Elizabethans (especially Shakespeare), Greek tragedy, Büchner, Wedekind, reasonable ground stimulations, the Bavarian folk play, and some more. Such a wide assortment of sources may have demonstrated overpowering for a lesser artist, however Brecht had the uncanny capacity to take components from apparently incongruent sources, consolidate them, and make them his own.."

In his initial plays, Brecht tried different things with dada and expressionism, however in his later work, he built up a style more suited his own one of a kind vision. He loathed the "Aristotelian" drama and its endeavors to draw the observer into a sort of daze like express, an aggregate distinguishing proof with the legend to the point of finish self-insensibility, bringing about sentiments of fear and feel sorry for and, at last, a passionate cleansing. He didn't need his group of onlookers to feel feelings - he needed them to think- - and towards this end, he resolved to obliterate the dramatic fantasy, and, subsequently, that dull daze like state he so disdained.

The consequence of Brecht's examination was a strategy known as "verfremdungseffekt" or the "distance impact". It was intended to urge the crowd to hold their basic separation. His hypotheses brought about various "epic" dramatizations, among them Mother Courage and Her Children which recounts the tale of a voyaging shipper who procures her living by taking after the Swedish and Imperial armed forces with her secured wagon and offering them supplies: dress, sustenance, schnaps, and so forth... As the war develops warmed, Mother Courage finds that this calling has put her and her kids in threat, however the old lady obstinately declines to surrender her wagon. Mother Courage and Her Children was both a triumph and a disappointment for Brecht. Despite the fact that the play was an extraordinary achievement, he never figured out how to accomplish in his group of onlookers the apathetic, logical reaction he fancied. Gatherings of people never neglect to be moved by the predicament of the determined old lady.

In Galileo, Brecht paints a representation of an energetic and tormented man. Galileo has found that the earth is not the focal point of the universe, but rather despite the fact that the Pope's own particular cosmologist has affirmed this world shaking disclosure, the Inquisition has taboo him to distribute his discoveries. For a long time, Galileo holds his tongue. At long last, another pope known for his edification rises to the Papacy, and Galileo sees his possibility. Be that as it may, the Grand Inquisitor is hiding out of sight, plotting to obliterate the colossal stargazer's work.

Brecht would go ahead to compose various present day artful culminations including The Good Person of Szechwan and The Caucasian Chalk Circle. At last, Brecht's crowd persistently continued being moved to dread and pity. In any case, his trials were not a disappointment. His emotional hypotheses have spread over the globe, and he abandoned a gathering of devoted followers referred to today as "Brechtians" who keep on propagating his lessons. At the season of his demise, Brecht was arranging a play in light of Samuel Becket's Waiting for Godot.

Bertolt Brecht died in 1956. He is buried in Berlin.

loading...

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed