|

So this is the Anthropocene: An historical time, perhaps even a geological time, in which what we think of as separate entities, the human and the natural, find their fates entwined. What was once a separate nature or environment is no in place to ground us as us.

Not only is God dead, so too is ecology, that pantheistic place God went into hiding. The biosphere is no longer a self-correcting, homeostatic deity. The later civilizations, said Valery, know they are mortal. This last civilization know the Earth is mortal too. I feel like Nietzsche’s madman in the marketplace, saying such things. Nobody really wants to know that the world we inherited, the world of our ancestors, is already something unreal. People shrug it off, change the subject. Yet as Canada’s national poet Leonard Cohen once memorably put it: everybody knows. Everybody knows things can’t go on. Cinema knows it. One of the things cinema is there for is to find some kind of objective correlative for feelings that can’t be acknowledged. Maybe cinema is not about desire at all, or even anxiety. Maybe it is about seduction, of turning us aside from unacknowledged feelings, and slipping us into worlds of objects and relations that displace those feelings onto something else. Thus: perhaps all cinema is now about the Anthropocene. Its all about a sense that this is not a Never Ending Story. There is already a cottage industry starting up which reads cinema as cinema about the Anthropocene. Before joining that little workshop, I want to add another frame. Perhaps cinema is not just about the Anthropocene, but of it. Cinema is made of the same stuff as the rest of this civilization. It is part of the very thing that can and will be made into something else. Alongside architecture, cinema is perhaps that art which the most vast consumer of resources. Unlike architecture, what is built for it is temporary. Its sets and props and vehicles are made to appear rather than to be. Sometimes there is a veritable potlatch of all these beautifully but temporarily made things staged for the film itself. Cars crash, towers explode in fireballs. Cinema is an allegory for the fiery ends of the world. Sometimes cinema’s scenery are left to rot. There are archeological ruins of ancient cities in the Nevada desert.

loading...

Cinema is also a prodigious consumer of energy. In New York, and I imagine also in Toronto, you can often see the mobile generators parked on the street to make the 3-phase power to run the show. Cinema, like pretty much everything else, is congealed fossil fuel.

The deep time of the earth is quite literally strip-mined to make the quick-time movies of our era. According to Jussi Parikka, in The Anthrobscene, 36% of all tin, 25% of cobalt, 15% of palladium, 15% of silver, 9% of gold, 2% of copper and 1% of aluminum goes into media tech. As he says, “deep time resources of the earth are what makes technology happen.” The ruling class of our time, what I call the vectoral class, got us used to thinking of information as something weightless yet special; easy-access yet always somebody’s property. They doesn’t like to talk about how much energy it takes, or how much infrastructure, or the weird shopping list of elements that have to be extracted from the earth to make the stuff run. Not to mention the trash-heaps where all our devices end up. Out of sight, out of mind. Cinema is like a bright brief digital dawn across the surface of devices destined to spend the eons again buried in the analog night. Cinema is then both about the Anthropocene, and of it. Watching the previews for the next season’s movies, they all seem to me to belong to the genre of the Anthropocene. They all seems to be narratives about a civilization confronting limits of its own making. Some movies, like Spring Breakers, respond by stressing the glorious expenditure of energy, burning it up with images of fast cars, fast planes, fast women. And guns, lots of guns.

Other opt for apocalypse. If the present cannot go on infinitely expanding then it can only collapse. No qualitative change can be imagined in narrative form. After us, the deluge: the Sun King’s prediction democratized. Cinema is having a hard time getting out of repetition.

Edge of Tomorrow is an interesting variation. Yes, it’s a Tom Cruise action sci-fi concoction, but these are not without their charms. Tom’s face provides the machinic sheen against which robots and aliens seem warm and somehow human. There’s a creepy shot of his right ear that keeps returning, again and again, with weird stretch marks, as if someone has shrouded a Mills grenade in cling-wrap. Setting Cruise aside, Edge of Tomorrow is interesting for a few reasons. The story’s mechanic is pure video game. Cruise and his co-star have the special property, bestowed on them accidentally by invading ‘aliens’, of starting the action over again, every time they die. Edge of Tomorrow lives out – and dies out – a desire for do-overs, for digital time. The time of the edit suite, as well as of the video game, where metered, reversible real time is real time, and duration is unreal, as if Bergson had it backwards. Edge of Tomorrow is about video game time, where death is not final, not an end, but rather a beginning, a do-over. Tom and his co-star do time over and over, trying to beat the aliens, clearing levels, backtracking out of dead-ends, all the way up to the boss level. But the time against which they fight with this video-game time is not duration, it is rather the historical time of the Anthropocene. It’s a human wave assault, by the most advanced flesh-tech of this civilization, against the very limits it has itself created. It is not an exaggeration to call this historical time in the movie one of civilization. The aliens have conquered Europe. Russia and China are holding it at bay. The decisive battle is a re-staging of D-day, across the English channel. The movie charmingly presents the Brits as nothing more than a front for American imperial power. But in a way all of the current variants of capitalism as a civilization confront the same enemy. The fantasy, then, is that the digital time of this civilization – be it capitalism still, or something worse – has within its power the ability to overcome the almost shapeless, formless, seething tentacle menace of the Anthropocene. One which curiously seems to have some sort of mimetic power. It doubles us and confounds us. It erupts from the earth or out of the sea, or appears out of nowhere in the sky.

loading...

The Anthropocene is an almost molecular enemy. It is techy, like us, and yet not. It is perhaps the shadow image of our own forces of production, mediating between earth and air and water, and bringing fire. It is very scary except in those moments when the film makers lose their nerve and give it a face.

Tom and co-star alone confront this Anthropocene alien with the digital power of do-over time. The co-star is Emily Blunt. She is the perfect embodiment of the weaponized woman. We see her tanned and oiled arms as she does push-ups in a black-ops chic sleeveless number, the camera lingering just a bit over her ass. The casting is a masterstroke. Blunt plays the global archetype of the stiff-upper-lip-Brit, mixed in with a bit of thorny English rose. Blunt’s performance is so on-point that she makes Cruise seem almost human, just as Cruise makes the aliens seem like they are actually us. I won’t give away where they confront the boss alien, but it is in a landscape under water. Weird weather as a feature of a lot of movies of the Anthropocene. It can be caused by anything at all, except the emission of green house gases from the collective labors of this civilization. This is key. The cinema of the Anthropocene is about anything but the causes of the Anthropocene. But it is very candid about its effects. So the boss-alien is confronted in old Europe, from which this civilization’s mode of production sprang. We see old Europe under water, as indeed in a way it already is, in the future already pre-set for it. Edge of Tomorrow secretly longs for a time of do-overs, to use this magical temporal capacity to confront the very mode of production that created it. Cruise and Blunt: perfect names for our heroes, for the two affects that dominate the action. And of course they win. There may be a point to this. If we could prefigure all of the permutations of the narrative resources of this civilization, run through them all, have all our futures over and done with in advance, we might be done with this whole narrative formation. Perhaps we need to play this game till we get bored with it. Perhaps we will get bored with it soon enough to discover that its digital time does not accord with the historical time of the Anthropocene. That other time is out there, like a formless alien.

Gravity is a rather different way of figuring the Anthropocene. It’s a bubble film, like Lost in Translation, but in this case the bubble is absolutely literal: the bubble of the space suit or the space capsule. More than once we see the earth itself, the biosphere bubble, as if to gently suggest to the viewer that Sandra Bullock’s bubble-trouble is really our own. The space suit becomes objective correlative for feelings about bubbles so expansive they take in a whole world. “I have a bad feeling about this mission,” as George Clooney says. We all have that feeling.

In Gravity, the bubbles start bursting as an unintentional side effect. The Russians shot down one of their own satellites, causing a whole cascade of chaos. As Stephanie Wakefield says in an excellent essay on this film: “the infrastructures that were supposed to have mastered and perfected the world not only cannot, but moreover it is increasingly from within these networked infrastructures themselves that disaster emerges.” Or as George Clooney says to Sandra Bullock: “pretty scary shit being untethered up here isn’t it?” It’s a romance story, except our romantic leads are not able to grab hands in the clumsy gloves. Like in Titanic, he will sacrifice himself for her. As if to say the world has no use for masculinity any more, but it will still have to make a spectacle of its uselessness. Gravity is a good news story, in that – spoiler alert – Bullock finds a way to end the Anthropocene. She finds a way to make contact with the earth, to emerge from the bubble into the waters, to be reborn on the shore, face pressed into the loam. Clooney the old-fart military man gives her the confidence. Its not that hard to pilot a Soyuz re-entry vehicle. Says Clooney: “You point the damn thing at earth. Its not rocket science.” And yet she crashed the Soyuz escape pod simulator every time, back when she could practice in do-over digital time. Cinema prefers to restage the crash, over and over. Gravitywants to hold out hope that when we have to re-enter for real we’ll pull it off. Sandra will pull through, shrug off her guilt, her mourning, her death-wish, her distraction, her compulsive hiding out in specialized labor – that in the moment the training will kick in and she will know what to do. The training – the simulator – is cinema. A kind of cinema that does not quite yet exist, of which Gravity is a hint. Cinema for the Anthropocene. Not about it, but for it. Stories of courage, of hacker adaptability. Just in case. Sandra: “Either way, it’ll be one hell of a ride. I’m ready.” “What now?” Sandra says, as her second of three possible survival bubbles goes up in flames. As the space-shrapnel hurtles in, the screen turns into a weightless version of the final scene of Zabriskie Point, only now the exploding detritus will not fall back to earth, status quo restored. There is no equilibrium point. There is no gravity. Everything will keep spinning off. The God of restored balance is dead. That is what Sandra mourns. Her dead child is the objective correlative for the melancholia of unfigurable loss that is the ground tone of the times. Twice we get to see Sandra take off a space suit. The first time its like a photo-realist Jane Fonda in Barbarella, a weightless strip-tease, safe for a moment at least in the space-capsule bubble. The second is under water back on earth, struggling for dear life to shrug off its weight. “So this is your wilderness. Detroit,” says Tilda Swinton to Tom Hiddleston in Only Lovers Left Alive. The vampire genre solves a major problem with the narrative frame of the Anthropocene. Nobody lives long enough to really experience geological time. These characters do. Says Tilda of Tom’s Detroit: “But this place will rise again. There is water here. And when the cities in the south are burning. This place will bloom.”

Tom takes Tilda, to see the ruins of the Michigan Theater in Detroit, which among other things was a movie house, and is now a car park. The vampires cherish the artifacts of industrial civilization, its records, cars, guitars, but above all its art, its literature and music, and particularly romantic art. As if to say romanticism’s sense that real is always elsewhere were the thread that points to what might one day be left alive. “I’m a survivor baby,” says Swinton, as the lick O-negative popsicles. Meanwhile Amanita Mascaria mushrooms bloom unseasonably, “behaving rather strangely,” these objective correlatives.

Sometimes seen as a true-love movie, the truth of Only Lovers Left Alive is in its last few seconds. Having run out of black-market blood donor sources of food, the two vampires bare their fangs and pounce on two young lovers in a quiet cul-de-sac in Tangiers. The vampire here is at once the figure of art, which will always find a way to be left alive, but also the figure of the white western vampire of the vectoral class, which would like to think it has reformed its ways, but maybe not. T. S. Eliot had the nerve to criticize Shakespeare’s Hamlet on the grounds that Hamlet gets too emotional. His intensity lacks an objective correlative, an object or situation that might compose and constraint affect, make it into art. In her book Heroines, Kate Zambreno insists on a need to undo this as part of a project of feminist retrieval, of putting back into the frame or onto the page the raw and messy business of emotion without aesthetic deflection. In her case, it’s a matter of putting back women’s lives: that of Ophelia, or Eliot’s long-suffering wife Vivienne. Perhaps it’s a line of inquiry that can be extended even further here. If we are done with woman as muse, perhaps we can be done also with nature as backdrop, as setting, as scenery. As something that is either to be put in its place or which when not becomes a raging monster. Perhaps its time for new worldviews. Or new old. Perhaps it’s a question of re-edit of how we see worlds. And how we see cinema. In this case, it would be a matter of shifting focus firstly from foreground to background, of seeing what cinema has to say about ground rather than figure. One could start with that genius work by Thom Andersen, Los Angeles Plays Itself, but pull back even farther. And secondly, it might be to ask about cinema as both a practice and a representation of energy using systems. Maybe there’s a certain homology, it how cinema likes to show the consumption, and at the same time depends on it.

[*This is based on a talk I gave at York University for the Cinema and Media Studies Graduate Student Conference, ‘Imagining the Crisis’, 21-23 November.]

loading...

0 Comments

Multiple Iterations: A scene from David Cronenberg's 'Existenz' (1999).

POST-MODERN AFFECTIVITY

What is the relation of film to our contemporary age? We live in a world today in which our affects, namely, our thoughts and emotions, whether caused from within our without, no longer correspond to the classical unities of the past. No longer do we feel like unified subjects, no longer do we chase unified objects, or act in unified plots or in unified settings. Rather, these are all shattered, and recomposed in new transvidual composites, the logics of which we are only beginning to understand. We need a cinema that can give use affects to match those we experience in our times, and to help us imagine film-worlds which can help point the way, which can help us orient in our actual life-worlds.

Science-fiction films, films of madness, amnesia, horror, dreams, drug-states, and time-travel, all these films have lead the way. They have given us the films that best capture the affective states relevant to our postmodern times. And yet, they so often seem to need to justify the structures whereby they produce these affects with tropes such as high-tech machines that allow time travel, or magical portals, or ‘it was just a dream’. These films have pushed the traditional plots to their breaking points, and yet, often feel the need to recapture what they have shown us within something that can reconnect with more traditional film-logics. But what if we made films that directly attempted to speak to the affects relevant to our age, without having to justify themselves via reasonings tied to the limitations of the ‘real world’? Or what if we at least gave ourselves the option? A film-world does not need to follow the limitations of the world, and it can impact this world even if it does not share these limitations. The history of film is full of examples of powerful films that dispense with aspects of the real world. Why not aim to produce affects directly, and structure films around them, rather than only producing them openly when we can justify a link to ‘the real world’? The cinema of affects does not need to imagine it is inside the mind of a mad person to produce a cinema like madness, or to imagine there are time travel machines to produce a cinema like time-travel. For to live in the world today, to hope and dream and remember, is already a form of time travel, a form of madness, it feels like this, and we can think these sensations even without the scaffolding provided by plot devices like madness or time-travel machines. Which is not to denigrate such films, for they are those which speak to us now most powerfully. But we need to learn from these films, and not be limited by the aspects of them which are swiftly seeming out of sync with the needs of the times.

Some have decried the first stirrings of the cinema of affects, the loose character formations, dissociated settings, and plots ever more baroque, as precisely that which should be resisted. And yet often these films speak more truthfully to the needs of our age than those films of the so-called ‘real world.’ Isn’t film supposed to speak to the world we live in, rather that of the past?

Take a film such as Christopher Nolan’s Memento (2000). Is not the short-term memory loss of the protagonist not an incredibly apt metaphor for what it feels like to live in our post-modern age? And yet, rather than decry the death of memory, we need to wonder, why might it not be possible to find a love, a poetry, within such a world. The protagonist in Memento learns in the end to gain agency over his seeming powerlessness, but does so in a brutal manner. But might it not also be possible to find a way to love in such a situation as well? Rather than yearn for the past, might it not be possible to wonder if there might not be room for new forms of goodness and love in such a world? And might not film be able to begin to show us how this could be possible? CHARACTER

Too long film has been held hostage by the notion of the character, and the main character, or protagonist, in particular. This is not to say that film does not often become more powerful when it is focused by means of a unifying perspective, a single film-consciousness that serves as a tour guide through the film-world being portrayed. Alternately, a few such perspectives, or a series thereof, may serve as a focusing device. However, these tropes should be seen as means, not ends in themselves.

While a unifying perspective of some sort is often helpful in promoting identifications of various sorts, and for unifying the filmic experience, it is important to keep in mind that these functions do not need to necessarily be anchored to a character that resembles a person in the so-called ‘real world’. Why does our protagonist always need to wear the same face? Be played by the same actor? Have the same voice? Use the same name? Live in the same house? Work at the same job? Have the same set of memories, or the same set of character traits or dispositions for dealing with the world? A character in a film is not a person in real life. A character is a means for creating a unifying perspective in a film which can orient the viewer and potentially serve as a site for potential identifications of varying sorts. A character is a function, composed of a set of variables, such as a name, a face, a voice, a point of view, a set of actions, a set of memories, each of which can remain static or change over the course of a film. In traditional cinema, a unifying perspective is always tied to the same body, voice, set of dispositions, memories, etc. In the cinema of affects, however, these all may be varied, associated or dissociated, depending upon the film-world in question. For example, imagine two characters lying in bed with each other, making love. When they cease, and begin to speak again, we realize that they have switched names. And as they rise from the bed, they put on each others clothes. They go to each others jobs, and seem to have switched roles in life. Why is this not a possibility for cinema? It speaks to us emotionally, and we can make sense of it intellectually in a wide variety of ways, even as we realize our world does not work like this. But this does not mean we cannot be powerfully transformed by having seen such a film.

The question shouldn’t be if it is realistic that people can switch like this, but rather, what it makes us think or feel, and how this resonates with aspects of the world beyond the film. So-called ‘realism,’ the ‘reality’ that resonates with a dominant image of the world, is only useful to film to the extent that it serves the production of affects. For the goal of cinema is not to reproduce the world, but to affect us. This has always been the case, and while the cinema of affects may choose at times to harmonize with dominant notions of ‘reality’ when it serves its needs, it also must free itself from thinking it must follow so-called realism simply because it must.

Otherwordly and semi-worldly art and theory have been incredibly powerful throughout history. The history of religions and ideologies, arts and philosophies, all this is evidence enough. Why should film do any less? No painting has ever been true, nor any novel or film. The desire to make film true is the only way to make it lie. Likewise, the only way to make a true film today is to make it deviate from the traditional notion of the character. For example, so many of the powerful films produced today have characters which are multiple sides of the same character, shattered in fragments. A film like Death by Hanging (1967), by Nagisa Oshima, is a clear precursor of this notion. Oshima fragments the general psyche of the post-war Japanese nation into an ensemble cast so he can play the parts off each other. A character has amnesia, the others try to restore his memory by teaching him about his past, they enact it, but find they eventually need his help, the scene degrades into parody, others from outside are recruited, but then reenacting violence leads to real violence. The whole troupe shifts locations as if transported through space and time into the streets of Tokyo, onto the top of a building, then back indoors where they started. Some now see a murdered woman, others don’t, then some that didn’t originally see her begin to. She starts out as a victim of murder, but then she wakes up, and begins to call the protagonist brother, but why then does she act as if she wants to make out with him? If one tries to make sense of the film as one of madness, it is impossible to tell exactly who is mad, or perhaps if what we are seeing is some sort of collective, transindividual madness. But why then would they all have such an odd hallucination? And why do so many of them act so strangely, hyperbolically, as if parodying themselves?

Only as the fragmented shards of the Japanese national psyche dealing with the guilt and fear and recriminations and denail of the post-war period can the film begin to make sense. The film affects us powerfully, its statements sear our brains, its psychological probing calls postwar Japan to task to deal with its past, and yet, what we see cannot be unified with the so-called ‘reality’ of any individual character. For in fact, we are watching probably one of the earliest examples of a truly transindividual film. And no attempt is made to justify how it is that we are magically transported to different locations in space, whether this is reality or fantasy, or many other details whereby the film seems to deviate from so-called ‘reality.’ We never learn why the woman just appears inside the room with them after they first hurt her outside. And yet, the film is not in anyway incoherent. Rather, it follows an immanent logic so tight that it could not have been any other way. As transindividual fantasy, one which develops like an organism, the film is completely rigorous, and as such, it affects us’deeply.

How did we get here? Transvidual fantasy in Nagisa Oshima's 'Death by Hanging' (1967).

Such devices can be seen more frequently employed in contemporary film. For example, in David Lynch’s Lost Highway (1997), two sides of a character change places in the middle of the film, such that one side of the character goes to sleep in a jail cell one night, and the other wakes up in the same cell the next morning. This could subvert the film, for it breaks the link of identification that films usually establish between spectators and a protagonist. But Lynch makes it work, because his film coheres according to a structural logic of its own that allows us to link up patterns between the characters, to derive meanings from the repetitions, mirrorings, echoings. It is not that reality is dispensed with, but rather, there is simply another reality, one with another set of rules. Thus each side of the protagonist chases a separate side of his wife, such that the film has a logic of its own, if one different from so-called ‘reality.’ But one with rules, nevertheless, rules which reveal themselves slowly to us as the film progresses. It is these immanent rules which determine the structure of the film, not the needs of a character, or a stereotypical plot.

If Lost Highway is a binary film, Lynch’s Mulholland Drive (2001) is, in some senses a supra-individual film, for all that we see in the film is a shard of the consciousness of the main-character. Entire characters may be figments of her imagination, or reworked warpings of the world around her, according to a logic which slowly reveals itself to us as the film progresses. At no point in the film can we be sure that what we see is unfiltered reality, there are only scenes which seem more or less real than others. Characters that don’t resemble each other at the start of the film slowly begin to resemble each other more as the film moves towards its primary climax.

Similarly, in David Cronenberg’s Spider (2002), one crucial character slowly shifts to look like another as the film progresses, and it is by means of this shift that crucial information is revealed. In a film such as Oldboy (2004) or Cut (2004, included on the omnibus releaseThree Extremes) by Park Chan-Wook, it is likely that the entire film-world is as if the dream of a character not depicted in these films, which yet needs to be postulated in order to unify the character fragments who compose the ‘characters’ of the film. If Mulholland Drive is a supra-individual film in which some notion of a world beyond creeps through, this possibility seems to vanish in Park’s films, and yet, these films retain their coherence because of the clarity of its mirrorings, plot-twists, and other structuring devices. While these may not be those of the so-called ‘real’ world, they increasingly feel more and more relevant as the world begins to look more and more like aspects of these films. In another contemporary film such as Sion Sono’s Noriko’s Dinner Table (2005), two of the main characters are young girls who run away from home and begin to work for a firm that rents out actors to play family members for people with no families. Their father tries to find them, and comes to learn that they are now in this line of work, and that due to the dangerous nature of the people who run this organization, the only way to find a way to meet with them is to have a friend hire his daughters, and then show up in his place at the last minute. As his own daughters walk in, everyone pretends to stay in character, even as their real selves begin to leak through. When those who run the organization show up and try to break things up, things get bloody, and each person strains to play the role in the fiction they have created, and yet their original selves begin to merge with these characters, as well as their desire for new selves different from both of these. Without resorting to time-travel or amnesia, Sono has constructed a film in which there are multiple selves inside each self, fighting with each other, shattering the subject, even as these subjects are intertwined within group subjective dynamics. It becomes hard to tell individual from group subjects from parts of subjects. The film is incredibly powerful, and speaks to so many aspects of our times, such as the disintegration of the family, the attempt to develop new avatars, the need to find ways of connection in and despite our multiple selves. And it does so through and beyond traditional notions of character.

Some may say that such a film is terrible, for it destroys human subjectivity, reducing people to mere placeholders for emotions and thoughts and words which transect them. And yet, what if such a film is also exploring the potential for new forms of subjectivity? Might we simply be fearing change? Might there not be a way to make a film like Noriko’s Dinner Table, not themed around horror, but rather, around love?

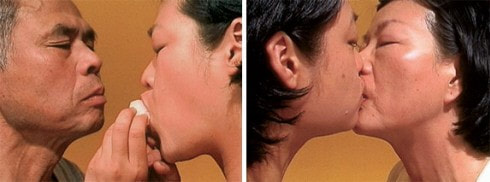

Perhaps the start of such an endeavor can be seen in a film such as In Love (2001), by Patty Chang. In this short two-channel video installation, one channel has Chang and her mother, the other Chang and her father. Each pair eats a raw onion together, from two sides, eventually kissing deeply as they devour the final parts of the onion. Both video-loops are played backwards, however, so that the onion emerges from their kissing mouths slowly, via reconstruction. The faces move from pained unity and uneasy intimacy, eyes burning with tears, to much safer isolation. The installation is intimate and powerful, and expresses the shared love and pain of a family, each member of which eventually becomes as many sides two onions, two channels, one experience shattered in twos and threes. The installation is nevertheless, quite short. What would a longer, more complex film of this sort look like? And might it not be necessary to fully dispense with the dynamics of development which a narrative, fictional or real or in-between, might bring?

Transvidual Affect: Patty Chang's 'In Love' (2001).

None of these films dispense with all structure to their characters. But neither are they constrained by the rules which would apply to so-called ‘realist’ cinema. In the cinema of affects, there are always rules, but immanent ones, ones not imposed upon the film from without, but rather, which rise from within a film’s own structure. Some of these films may opt for more poetic, metaphorical, or intellectual linkages between aspects, while others opt for narratives, plots, developments, repetitions, mirrorings, similarities, etc. No matter what sort of unity a film opts form, we should judge a film not by its accordance with some pre-concieved notion of reality, but rather, what it makes us feel and think. Such is the criteria which governs decisions in a cinema of affects.

FILM-OBJECTS

Cinema does not only have unifying perspectives. It also has entities, film-objects. These entities may be parts of unifying perspectives, or they may be relatively autonomous. Objects may be relatively inert, in which case, they are rarely distinct from settings, or they may be profound, filled with meaning, like HItchcock’s objects, spiritual objects, magical objects, desired objects. Characters desire objects, fight for objects, destroy objects and desire each other as objects. Objects may warp cinematic space, draw us to them, repel us, force actions on characters, create events. Objects are the exterior reflections of characters, and the concretization of the tensions in settings.

An actor picks up a knife, with intent to kill. The perspective that the character provides us with makes the act of picking up a knife feel real to us, and we can identify with his world by seeing through his eyes. The character is dynamic, the knife relatively passive, and yet it is also as if, in some sense, the knife transforms the actor, and a change comes over him. Now, imagine the same scene, we see the actor, and then the camera closes in on the knife. But as the camera pulls back, we see that the actor has changed into a different actor now that the knife is in hand. Rather than assume that characters retain the same body over time, the knife has changed the body of the character, from a pre-murderer into a murderer. Why not express this change in this way? What prevent us from doing this? Ini the real world it is not possible to change body as one changes life-mode, but why constrain ourselves? Here the function of the character may include continuity of action, but not of body/actor. Another possibility, often used in the films of Cronenberg, is to have an object slowly mutate from scene to scene, as if it were nearly alive or possessed by a force from beyond. Maya Deren presents perhaps one of the earliest examples of this by means of the mutation between knife, shard of mirror, and key in Meshes of the Afternoon (1943). We see something similar yet more nuanced happen in Cronenberg’s Videodrome (1983), as the protagonist’s gun-hand mutates each time we see it.

Things may not be what they seem: a labyrinthine play of mirrors provides structure to Christopher Nolan's 2006 film 'The Prestige.'

Such progressive mutation is part of the very fabric of the world in his later film Existenz. In Existenz (1999), there are multiple iterations of characters, scenes, actions, objects. This film as video-game about a video-game tracks the serial aspects of our contemporary world like few others. Here the video-game system which serves as the central conceit of the film serves as a device whereby to explore forms of fragmentation that speak to our contemporary life world. One could imagine such a film without the video-game device, and we should not think this would make the film better or worse, merely different. But we should also realize that if we extract the ways in which such a film deals with iteration as such, this becomes yet one more tool to be used in cinema, whether or not we justify by means of plots devices such as extremely powerful video-game consoles.

No longer should we have to ask whether or not a cinematic technique is allowed, but rather, what it produces. Why not have all the objects in a film evolve in this manner, or reflect aspects of the character? Why not change the objects in a film to reflect aspects of the action? We see some aspects of this in the manner in which directors since the begining of color film have coded some characters with a particular color of clothing, or matched the clothing of a character with that of an object in a room or aspect of a setting. Why not extract these tools and consider them all fair game? Whether or not we tie them to plot devices like time-travel or dreams is up to us, but we should acknowledge the power that mutating, multiple objects have on us today. In a time of iPhones and iPads, of objects that seem to feel and think, does it surprise us that our film-objects have become uncanny, multiple, powerful, labile? PLOT

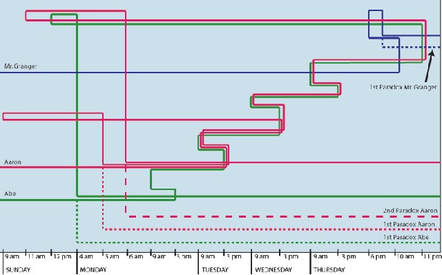

One critic's depiction of the time loops that structure Shane Carruth's 2004 film 'Primer.'

A plot is a series of events, and events are transformations in situations. A film begins, and a situation is laid out for us, composed of parts like setting, character, desires, etc. Minor actions may occur, but an event transforms the balance of entities and forces in a film-situation. A character shifts from being good to bad, the world is rocked by an earthquake, a murder occurs, the situation changes. These are events, and we string them together into plots.

And yet, in postwar film, we see how plots may not only be linear, but rather, may be a crystal of event-parts. Time-travel films, films of madness, science-fiction, films of the amnesiac, these films scramble the linearity of traditional plots. An amnesiac exists with no past, then slowly begins to remember, just like in our postmodern age we are so overloaded with narratives and information it is as if history has disappeared. We constantly need to reconstruct it from fragments, like the amnesiac. And in a world in which the past seems mutable, and the future composed in relation to such a past, doesn’t time-travel speak to the way we feel living in the present, wondering how to change who we are so as to harmonize our now seemingly multiple pasts, presents, and futures? By means of films of time-travel and amnesia, as well as films with similar temporal structures composed of loops and other figures beyond the straight line, we have staged what it feels like to live in our postmodern age. Seeing our uncanny double stealing our memories speaks to us more vividly, in the age of Facebook, than a cowboy shooting a bad-guy on a dusty plain. We need twisted plots in which we meet our own clones, and our clones are more real than we are, and then these clones produce clones which turn out to be amnesiacs. In a hall of mirrors, which Deleuze calls the crystal-image, before and after becomes relative, and time ceases to be linear, but is more like a knot, gem, or four dimensional sculpture. Only these sorts of films feel real to us today. This is not to wish for simpler times, for even clones can fall in love, or have radical politics. Evolution does not go backwards, nor should it. Just as uni-cellular organisms learned to work together to produce more complex life forms, humans can work together to produce transvidual entities, like language, or Wikipedia. And increasingly, this is becoming the rule, transindividuality is a radical series of new potentials for our future, even if it can also go radically wrong. Like all futures, there is great potential for good or bad. And we must learn new forms of love and solidarity for fragmented times. We live in an age in which we are all time-travelers, schizos, amnesiacs, space-travellers, if metaphorically. The question is not about going back, but learning how to make the new world livable, ethical, and just. For as the digital age has fragmented everything it has touched, unleashing potentials for radical good and bad, so cinema must respond by finding new languages of fragmentation which speak to the needs of the times. Why must a plot follow a main character? Why not follow instead the permutations of a unifying phrase? We long to see dynamics and change, this is how a plot hooks us, we learn a situation, then we become curious to see how it will develop its potential for change. But we need not follow the old plots based on traditional characters overcoming traditional obstacles.

The time-travel machine from 'Primer': Strands of time emerge in many directions, or, does the same device simply ingress in multiple moments in time?

Take once again a film such as Mullholland Drive. The pull of curiosity that keeps us glued to this film is not the overcoming of some pre-established obstacle, but rather, to learn how the film will eventually cohere from the set of fragments which have been presented to us. What a better way to hook to the desire of a spectator to a film? Curiosity about the structure can supplant the traditional form of narrative plot. And just because the characters blur and fade into each other doesn’t mean we don’t care about them. The scene in the middle of the film, in which the singer on the stage collapses, is one of the most powerful in the film, and yet, we see this character for only this scene. We need to understand the power which such suspended moments, outside linear plot, can present to us.

A film is nothing more than a collection of film-elements composed so as to create a whole. Film-elements unify to form film-situations, and these are modified by film-events which link up to form film-plots. But these plots need not be linear, they can be looped and twisted via strands of time, moving forwards or backwards or something more or in-between, creating spatio-temporal short circuits in a wide variety of ways, blasting events open as they are criss-crossed multiple times by plot lines and become multiple. And as characters, objects, and settings multiply and mirror each other, short-circuits are produced, in which the very continuity of any object, character, or setting can be seen as a repetition laden with difference in a film which is fundamentally crystalline, providing multiple pathways in time, of which linearity is only one option amongst many. Or perhaps we could even say that the same entities, objects, time-travelers and time-travel machines, perhaps stand still, and ingress in multiple moments of time, dipping into multiple strands of time like one would dip a toe into a stream? Might repetition from one perspective be multiplication from another? Many scientists have argued that perhaps there is only one photon, one light particle, in the universe, which simply bounces between many moments of spacetime. Why should film not be as strange as our realities? And even as objects, characters, and settings may repeat, why not even events, with or without a justificatory device such as time travel? Bergman first did this in Persona (1966), when we see the same discussion from two different perspectives. In ‘the real world’ this cannot happen, but in the film world it not only can happen, but in this film, it must happen, for we see the conversation from two different sides, the two sides whose uneasy difference-in-sameness, sameness-in-difference, is precisely that which is investigated by the film. And in Bergman’s film, we are never quite sure at which point the film actually veers off into memory, fantasy, or dream, for in fact, the point of departure is multiple. The film does not suffer from this, but rather, is infinitely stronger. For this very multiplicity is precisely the film-world which Bergman wishes to create, and which gives the film its power, that speaks to the increasingly multiply fantasmatic nature of our times. Our lack of ability to pin-point, as viewers, the boundaries between dream, fantasy, and reality in this film, all this mirrors the inability of these characters to distinguish themselves from each other. The film is a complete, interdependent gesture, and yet, it moves beyond the limitations of traditional film. Persona is a clear precursor to a contemporary cinema of affects. Or, take a film in which there are even three takes on an event. Kurosawa’s Rashomon (1950) presents us with three takes on the same incompossible set of events. Unlike Persona, we cannot simply see the film as two views of the same events, for these events cannot exist in the same world together. For Deleuze, a film like this is one of the earliest examples in film of what he calls the powers of the false. And beyond this, we can even imagine a film which is little more than a series of modifications of the same event (ie: the interruption of dinner, in The Discreet Charm of the Bourgeosie, 1972), such as we see in many of Bunuels later films.

Are these films any less powerful for being tangential to the so-called real world? For what could be more true to the reality of the period right after WWII than people who had seen the same reality, but seem to have read its meaning so radically differently? Rashomon expresses the disjuncture within reality that was part of the post-WWII age. And what expresses the futility of routine in the age of industrial capitalism, with its creepy mechanizations, better than Bunuel’s absurd comedies? Life under mechanization is like a dinner party that can never come to fruition, even as it repeats its failure once and again. Comparing industrial production to dinner, this is metaphor, the very stuff of artistic creation. It is what transforms the world into film-world, and creates affects. Of course, Bunuel’s film may be about much more than dinner, or industry, and here we see the polyvalent capacities of metaphor. But either way, we see how a plot can be non-linear yet potentially speak more powerfully to us than linear plots could.

Or take a more contemporary film, such as Sean Caruth’s time-travel film Primer (2004). As multiple characters start to travel backwards in time, producing a doubles of themselves each time, the world begins to proliferate with doubles which emerge from the future, with knowoledge of what is to come, trying to change the past. In an age in which we can see copies of ourselves recorded on digital film or video from so many different points in our lives, always looking different than we remember, might this film be more real than ‘reality’? And yet, this film is ultimately about more than just time travel, for it pursues the dissolution of trust between the protagonists in and through the use of time-travel, a world like the multiplicitous world of the present, in which selves multiply faster than we can keep track. We see a related trope in The Prestige (2006), Christopher Nolan’s mind-bending film which may or may not involve a machine that makes copies of people, or people who simply learn very skillfully to disguise themselves as one another. Which is it? The film pushes indeterminacy to the limit, as doubles proliferate. Pairs, series, lines, solids of reflections and refractions. But is this not closer to what it feels like to be alive today? For are there not so many people like us in the world, our doubles and triples? Variations on a series of themes? Might it not be possible to find someone else with nearly the same Facebook profile as you, who likes the same music, the same books, the same politics? The world multiplies permutations on a series of themes. And in today’s multi-mediascape, might we not encounter our doubles or triples at some point? Can we trust them? And can my favorite novels trust the favorite movies of my close friend that I’ve known for years?

Even clones can have trouble recognizing themselves: three faces of the same, Sam Rockwell in Duncan Jones' 2010 film 'Moon.'

Or take a film like Moon (2009), by Duncan Jones. This film is able to produce intense feelings between two characters who slowly come to realize they are each other’s clones. The plot of the film is wound around a repeating cycle of birth and death lived by new clones in succession, until two of the clones accidentally end up in the same place at the same time, figure out that despite the changes one has gone through that they are ultimately multiple iterations of the same person, such that one of them then tries to get out of this loop. What type of plot could be more real than this in today’s postmodern times?

Such a film is more truthful, more real, than anything contrived plot of a film up for an Oscar this year, a film with a plot just like the others. Such films are the real clones, zombies that drain our potential for what’s realer than real. As Slavoj Zizek has argued, what is truly real is the fantasies which determine the ways we imagine our relation to the world. On such a level, films like Moon or Primer are infinitely more real than a film like The King’s Speech (2010). Such films pretend to depict so-called ‘reality’, and yet what they really depict is tired old genre conventions repackaged in new clothes. And yet, if reality is not these genre conventions, and never was, why do we cling to them so strongly? These are yesterday’s fantasies, we need those which speak today. While nostalgia has it’s place, if we want to understand the future and present, we need more films like Primer and Moon, not The King’s Speech. To the cinema of affects, therefore, rather than ask whether or not the plot of a film is realistic, we should ask, what affects does it send into the world? How does a film make us feel, make us think? We do not need to have easy answers for these questions. But a good film will make us feel and think much, and we limit ourselves unnecessarily by relying upon the outdated unities of character, plot, object and setting to do this. Some films may continue to use devices such as cloning and time-travel, and be strong because of this, but some films may eventually dispense with these devices completely. Either way, so long as the film is structured around the affects it creates, rather than correspondence with outside criteria, it is an example of the cinema of affects. SETTING

The zone: a world radically remade, from Tarkovsky's 'Stalker' (1979).

What is a setting in a film? A background upon which unifying perspectives and functions and events and plots intertwine and unfold. Why does a character have to open a door and end up in the next room? Film has freed us from this need. Why not end up in the same room as one started in? Or in a forest? Just as we need to realize that plot and character are artificial unities when it comes to film, so it is with setting. Why does the same room need to always have the same furniture? Why not change it to fit the mood of the scene or the characters?

This is not to say such shifts are necessary. But they are possible, and whether or not we develop a plot device to justify such shifts (the character is insane, the character is dreaming) is up to us. A film which uses such shifts continually may be called magical realist or dreamlike, a film which never uses them may be called traditional, and those in between, that use such shifts highly selectively and in relation to highly constrained criteria might be called fantastic (ie: a quantum fluctuation machine creates transportation between locations, but only the machine is able to do this). These three forms are all modalities of filmic creation. For a cinema of affects, these are all tools in the toolbox, tools which may be used depending upon their ability to create affects. Of these, films of the fantastic, ones which take aspects of the dominant so-called ‘reality’ and warp them or modify them in various ways have perhaps the greatest potential for the cinema of affects. For example, in a film like Tarkovsky’s Stalker (1979), we see an ordinary industrial wasteland transformed into an alien landscape, simply by means of camera angles, and the strange tale told by the character known as the Stalker. His belief is transferred to the other characters, so that it becomes difficult to tell whether this strange landscape truly has powers in the film-world, whether there is a mass dream or hallucination of sorts, or whether the Stalker is able to influence the minds of the others by the sheer power of his belief. Either way, the setting feels completely. A set of weeds become incredibly dangerous, full of hidden powers, such that rituals are needed to cross them without disaster occuring. An ordinary doorway in a room in an abandoned building becomes the site for the deepest wishes and fears of the main characters to come true. Or take a film like Kubrick’s The Shining (1980), in which one can open a door and see a forbidden sexual act from the past. Such a spatialization of time transforms setting as much as it transforms plot. For example, as Deleuze has argued, we see such a device employed in Resnais’ Last Year at Marienbad (1961), in which the multi-doored hotel room spatializes time, each room holding what Deleuze calls separate ‘sheets of the past,’ even as the characters seem to jump between points of the present which never seem to line up with each other into a coherent flow.

When setting is loosed from the stabilities of the so-called ‘real world’, vision is liberated with it. The cinema of affects shatters the world to bits. And so it aims to suspend us before what it presents to us, to suspend its viewers judgment, so that they cannot know upon first viewing what it is they see and hear. In so many films by Tarkovsky, for example, we only learn what it is we see early on in the film once we have gotten to the end, for it is only at the end of his films that we begin to understand the lenses through which we are supposed to understand the opening segments of his films. And thus, we find that while we see and hear in the early parts of his films, he teaches us what it is to see without seeing, hear without hearing, or rather, to see and hear without knowing WHAT one sees or hears. Where does one divide between parts and wholes, foregrounds and backgrounds? Which aspects will be significant later? Nature in Tarkovsky’s films seems to pulse with hidden powers, powers to give birth to the racically new, and unleash within us a second sight, a multiple-sight of radical becoming. Tarkovsky is the prophet of a radically secular religiousity of the visible world. More than anyother filmmaker, Tarkovsky has taught us how to see differently, and most powerfully, to see nature differently. Never has an earthly landscape seemed more alien than that depicted in the opening scenes of Solaris (1972). And after the first viewing, never has nature seemed to be more than it was, a vision beyond vision, a vision made radically multiple, its productivity lurking between the strands of reeds, blades of grass, a holiness beyond any religion, a holiness of this world. Tarkovsky releases more than any other filmmaker the power of the film-world to transform everything. His settings are allegories for the radical power of film.

A cinema of affects must learn from this, it must seeks to suspend knowledge for potential, to show viewers the potential for worldmaking within each and every shot, within ever bit of sound and vision. As Tarkovsky has said, we must feel the pulsing of time in every shot, and if we read this through Deleuze, we can say that we need to be able to see the power of pure difference within each shot, for difference and becoming (not to be confused with more tame forms of time) are two sides of the same. Tarkovsky presents us with a pedagogy and a prophecy in his films, in which each aspect of each image has the potential to give birth to film-aspects and film-worlds to come. So it often is with the films of Lynch. Time invades the very atoms on the screen, for you never know where it will make a cut in reality from the future, which aspects will become meaningful in retrospect, often not due to one reversal, but perhaps many. Or what of Memento, in which every ten minutes our relation to the past reworks? Or a film like Nolan’s The Prestige (2006), in which there are so many plot reversals, that each time we thought we understood how to read the past, things are once again reshuffled, until we learn to navigate the plot, as well as the relations between objects and characters, in a mode of radical suspension which opens us onto the power of a radical futurity in the present. All of these powers of film need to serve as raw materials for a cinema of affects.

taken from:

A scene from Tarkovsky's 'Mirror,' (1975).

The use of audio and visual stimulation to impact, or affect, spectators/participants indicates one of the most powerful media formations of our era. Cinema, or film, is one of the primary ways in which this is done.

Film creates film-impacts, or film-affects, in spectators. Film-affects come in two forms, namely, film-thoughts, and film-emotions. Film-thoughts and film-emotions occur when the images and sounds in a film impact spectators in particular ways. Film-affects are always in-between, they are born of the intertwining of images and sounds and spectators. Film-affects describe the emotions and thoughts which occur when spectators and film interact in the act of spectatorship. For too long cinema has treated the traditional means whereby film-affects have been produced as ends in themselves. These means, of which characters, objects, plot, and setting are the most important, have dominated the production of most film in our century. Thus, it is often assumed by many that for a film to affect spectators, it needs a main character, a stable plot, and solid objects and settings. Avant-garde film, of course, does away with these means completely. And yet, avant-garde film, which often produces a pure cinema of the eye and ear, divorced from character, objects, plots, and setting, is often marginalized for being too abstract. Avant-garde films are often, though not exclusively, short, and generally have small audiences. And by dispensing completely with character, objects, plot, and setting, avant-garde film dispenses with incredibly powerful means for creating affects.

What if there were a middle path? If film is constructed so as to emphasize the construction of affects, it could hardly dispense with the four means described above. But it would not be bound to these tools as ends in themselves, but view them merely as means towards the ends of the production of film-affects. Rather than constants, character, objects, plots, and settings can function as variables, each composed of sub-variables. Such a middle path could be called then a cinema of affects.

A cinema of affects would neither allow itself to be dominated by character, plot, objects or setting, nor would it dispense with these notions. Rather, it’s goal would be the production of affects, namely, thoughts and emotions, in spectators. Characters, plots, objects, and settings may serve to assist this end, but they are ultimately secondary to the affective complex which the film works to articulate. In what follows, the outline of a cinema of affects will be articulated. Before getting to the specifics, namely, the issues of characters, plots, objects, and settings, however, we will describe the larger frame, namely, the theory of film which is presupposed by the call for a cinema of affects. Thus, we will describe what, from the perspective of the cinema of affects, is the relation between film and world, film and art, and film and contemporary times. FILM-WORLDS

What is the purpose of a cinema of affects? Each film that is produced takes the world around us and fragments it, warps these fragments, and then recomposes them into a new, synthetic aggregate. Rather than an image of the world, film presents us with a film-world. The film-world is the world as it appears in a particular film. That is, a film-world is the aggregate of the fragmentations, warpings, and recompositions of the world in a film.

Each film world is an abstraction of the world in which it is produced. As such, it can be thought of as a transformation, a process, which is enacted upon the world at a given location in time and space to create a given film-world. This process of transformation, composed of fragmentation, warping, and recombination, can be thought of as a lens, or film-lens, that transforms the world into film-world by means of the process of flimmaking. Such a transformative process is composed of many sub-processes. Thus, there is a film-lens specific to a given film, which is little more than the the complex aggregate of the film-lenses of each of its aspects, each of which is a transformed part of part of the world into film-world. Film-worlds present us new worlds which are possible sub-worlds of the world we live in. As abstractions, and static ones at that (for film is not a continuous flow in the manner of television, nor interactive in the manner of the internet or video games), film-worlds present us with finite productions. In the process, they give us views on to new ways in which the world can be. As temporary abstractions, they present models, which can impact the ways in which we dynamically abstract aspects of the world in order to interact with it on a daily basis. As such, films can teach us how to view the world with new lenses, film-lenses. While a film directly presents us with the film-world of its creation, it indirectly presents us the film-lenses which make this film-world possible. These film-lenses are transformations, processes, which can be applied to new material in the world beyond the film.

In this manner, film can teach us how to see the world with new eyes. For each film-world is a possible world constructed from the world beyond film. And each film-lens that creates a given film-aspect can then be applied elsewhere, to the world beyond the film. Film gives us new eyes and ears, it teaches us again to hear and see.

Many film-lenses cannot be directly transferred to the world beyond film. In films, we see people cast spells, dive into portals between worlds, and do many other things which are difficult to directly integrate into our everyday life-worlds. But films that break with so-called ‘reality’ can still affect us powerfully. These film-affects, which are emotions and thoughts produced by films, can lead to modifications in our world-lenses, that is, the lenses whereby we fragment, warp, and reconstruct the world into our own life-worlds, the worlds of our daily experiences. For each of us lives in a life-world which is to the world itself just as film is to this world. We are all filming, in a sense, if differently from the camera, simply to live our daily lives.We all fragment, warp, and recombine aspects of the world simply to live in it. Film is therefore analogous to life, parallel to it. In some senses it can be thought of as another life, and one which can affect us deeply. And just as life exceeds film, so film exceeds life, for the camera has potentials which exceed that of our bodies, just as our bodies have potential which exceed that of the camera. There are many ways in which film-affects may impact the way we lens the world around us. Films may affect the construction of our life-world directly, in that we may integrate aspects of film-lenses with our world-lenses, such that we see the world partially in a way that was revealed to us by film. This occurs when film-affects impact us deeply, we absorb aspects of film-lenses, and then fragment, warp, and recombine them with aspects of our current world-lenses. However, it is also possible for film-affects themselves to make us modify our own world-lenses without the absorption of film-lenses from the film. In such a case, the emotion or thoughts produced by a film lead us to alter our film-lenses on our own, without a process of absorption of the film lenses. Often a film will present us with film aspects which violate the norms of so-called ‘reality’, but which nevertheless may affect us powerfully. Such films can alter our world-lenses in a variety of ways.

For example, dream and fantasy are powerful tools which can impact the ways people see the world in a wide variety of ways. Dream and fantasy can teach us new ways to desire, remember, hope, fear, think. Films can make us want to change the world or ourselves to be more or less like aspects of the film-world. It would be a mistake to throw away any aspect of the tools of world-creation which film presents to us. For by means of film, we imagine new possible ways of seeing, hearing, and doing in the world.

A cinema of affects would use all the tools at its disposal to create powerful film-affects. It must not be dominated by the tropes of so-called ‘reality,’ for this would be to abdicate the power of cinema to create new worlds, rather than simply reproduce old ones. Nevertheless, a cinema of affects must also realize that to completely dispense with forms which have dominated the past is also an abdication of the clear power such forms have had. In between these poles, a cinema of affects would look to maximize the power of its affects to create powerful film-worlds, and therefore, it will use any and all tools at its disposal towards this end. For cinema is one of the most powerful ways to make the world new, and to make sure that the past does not dominate the present and future, but merely serves as a foundation upon which change can occur. When film does this, it works hand in hand with the larger goal of a democratization and constant renewal of the world. FILM-ART

Each film-world is a perspective on the world. These perspectives function as ideals, for they are abstracted and separated from the flux of life. These ideals re-enter the world of change and flux, however, when they affect us.

Abstraction, separation, and ideality are both gains and losses for film. As that which is abstract and ideal, film has the possibility of presenting forms of wholeness and completion, harmony and beauty, or even dissolution and debasement, beyond what we see in the physical world. For the physical world needs to harmonize a great deal of elements, while the film-world only needs to harmonize those aspects it selects from the world. This is why film can provoke such strong affects in us, such as wonder or disgust. Film inspires us to see the world anew, and yet, it always presents an abstract ideal. When this abstract ideal is beautiful, even if because of the harmony of its forms of putresence, we call it art. Film-art, as with all art, may impact us either because it is well crafted, or beautiful, because it is powerful, or sublime, or thought-provoking, or intelligent. Each of these may create strong emotions and/or thoughts in us, namely, film-affects, which may lead to a wide variety of potential actions. The result is world-poetry and world-prose with potentially wide ranging affects beyond film itself. We cannot know, as filmmakers, the extent to which the affects a film creates in us will be those it creates in others. The most we can hope for is resonance. And yet, because so many of us were formed under similar conditions, there is much in common between us, despite our myriad differences. The most we can do is form film-worlds that affect us, and which we believe will affect others similarly. Film-art production is a form of self-therapy. It is a way to envisage forms of harmony between our continually shifting pasts and potential futures and our perpetually disjunctive present. What functions for filmmakers as self-therapy may also become other-therapy. This is the hope of towards which all filmmakers strive, namely, that their own forms of artistic production can help not only themselves harmonize with their worlds, but others as well. And we need not think of the production of harmonization with our world as passive. To harmonize with one’s world is in fact to necessarily be active, to mutate that world as it mutates you. Filmmaking, the production of film-art, can be a large part of this. Thus we make film-affects, and aim to make more powerful film-affects, so as to more powerfully sculpt our relations with our world, to harmonize with its greatest circuits. For the more a film harmonizes with the world, the more it furthers the project of a deep sync with what is. Such a notion of sync would be far beyond adaptation, for it would be a transvidual world-becoming.

Film-art is a part of the world envisioning itself, in and through us. The more powerfully we create, the more our film has resonances beyond ourselves, resonances with the deep structure of what is. That is, the more a film resonates with the deep structure of the world, the more it is affected by the world through its creators, and therefore, the more it has the power to affect more than just the filmmaker, but also the world around it. And thus, the filmmakers must be able to be powerfully affected by the world, so as to powerfully affect it in turn. Filmmakers can become lenses themselves, part of the world’s own perpetual re-envisioning.

And our world is changing. Most recently, in the postmodern era, we have seen many of the unities of the past, unities often depicted in films by means of characters, objects, plots, and settings, starting to fragment and rework in radical ways. This needs to impact the ways in which we make films. For if film finds its power in its ability to create affects, why would we limit ourselves to the traditional film of characters, objects, plots, and settings, particularly if these forms are increasingly being reworked in contemporary society? Or conversely, throw these all out for a pure cinema of the eye and ear?Neither form speaks to the needs of our age as much as those which seem to cut in between and beyond these constraints, those which speak to the radical ways in which subjectivity, objectivity, narratives, and settings in our life-worlds are being reconfigured today. Might there not be more possibilities than films which tell stories, and those which show us a pure vision of the world? And perhaps might we also be able to create films which exist between and beyond these two poles, but also between the others which have structured film? These include the poles of fiction and documentary, porn and art, essay and entertainment, narrative and spectacle, and likely many more. A cinema of affects would reject all these polarities as limiting its potential to create film-art, film-worlds, and film-lenses to create film affects. Rather, it would see all of these as means rather than ends, and seek to push beyond limiting polarities. The cinema of affects therefore dispenses with the need for the traditional stabilities surrounding character, plot, objects and setting, even as it also dispenses with the pure cinema of the eye. It dispenses in fact with all such limiting binaries. Therefore, it also dispenses with the distinctions between fiction and fact, narrative and spectacle, eros and art, etc. In doing so, it absorbs many of the radical and avant-garde devices made use of by experimental cinemas of the twentieth century to explode characters, plots, objects and settings from within, while riding the boundaries between and beyond genres of the past, so as to make them serve the affective needs of the film itself, rather than the other way around.

taken from:

[Final installment of my series on reading Deleuze’s Cinema I & II. I’m planning to hopefully turn many of these posts into part two of my future book project The Networked Image, but first I need to finish the other network books which come first. But I wanted to write these thoughts down between now and then so I don’t forget!]

If Orson Welles is in many ways the hero of the first part of the sections on the powers of the false, Jean Rouch is in many ways the hero of the second part, and with that, of the Cinema books as a whole. The trick is understanding why. Let’s start off where we left off in the preceding post, discussing the powers of the false, picking up with the third power, namely, the cinema of thought.

loading...

The Cinema of Categories: From Genre to Noosign

Deleuze begins his analysis of the third power of the false with a discussion of what he calls the cinema of categories in the films of Godard. From his discussion of series of objects in the cinema of gestures (second power of the false), we move to that which connects powers represented in series into categories. Thus, a tree blowing in the breeze (a cinema-body exhibiting a power over time) is recognized as a member of a category of objects, for example, images of nature. But how are cinematic categories, that which helps us recognize objects, characters, actions, etc., produced?

In traditional cinema, we have the issue of genre, and there are genres of many types of things, genres of kisses, guns, entire film types, etc. Thus we have the Hollywood car chase, the Western, the slasher, the vampire, all these are genres, cliches, if you will, which can help us to recognize images as belonging to a category. Godard is the cine-thinker, however, who plays with categories more than any other. Some of his films are devoted to producing a parody of a given genre, some of his scenes parody those of other films. Some of his films use inter-title cards to announce a category, and then show us a series of images that seem to only vaguely relate to the category just announced. Godard liberates categories from cliche, shows us the process of linkage underneath them, shows us the male ability of cinema-categories. And in doing so, Godard presents us with a true cinema of thought. Deleuze describes cinema-thought as truly inaugurated by Eisenstein. Eisenstein, for example, in the famous section ‘On God and Country’ in October, shows us how a series of images could link together to produce a visual argument, simply by what was linked together in sequence, to produce a dialectic of thesis, antithesis, and synthesis. For Deleuze, what unites these images in series is ultimately the film-spectator, not shown on screen. But this spectator experiences the shock produced by these images, and must think, is forced to think, about what links them together.

Thus film can force us, as spectators, to think. When this happens, what we think is partly determined by the film (hence the force and shock aspects), yet part of it is also free. This conjunction of freedom and necessity puts us in a state like that of a trance, in which we have freedom (spirituality) and compulsion (automation), converting us into what Deleuze calls a ‘spiritual automaton.’ Film spectators in the process of thinking are precisely this, spiritual automatons. And since cinema is simply, for Deleuze, a special case of what it means to exist in the world, this is what we all are when we think. Each one of us in the world experiences a series of images on any given day, and the shock of the images we encounter forces us to synthesize them. We find ourselves between compulsion and freedom, we are spiritual robots. We think.

For Deleuze, there is a two-way motion here. Images in series are linked together by montage horizontally, yet thought which unites them comes to be on a higher level, vertically, so to speak. Thought can be extracted from a series of images in this manner. However, thought can also come before the images, such as we see when a filmmaker has an idea first, and then decides to try to find images to match them. This creative action shows in the ‘ingression’ of thought in the world. And here we see how it is that Deleuze attempts to recast the sensory-motor schema of perception, affection, and action, yet outside the limitations of the human. Film-thoughts and film-actions. Yet is it possible to think a film-body, namely, that physical entity which does the thinking and acting?

Sometimes a film will not only show us images, but also show us that which thinks a series of images. When this happens, we have a representation, via an image, of a physical body which synthesizes other images as a spiritual automaton, that thinks. A thing that thinks, for Deleuze, is what he calls a brain. Cinema can depict thought in two ways. It can have thought off-screen, in the form of an implied spectator, which presents us with one indirect imaging of thought, or noo-sign. But cinema can also present us with a body that thinks, and image thought as a noo-sign by means of this body. Thus, we have characters in many films that seem to think, that is, to process other images and synthesize them. Traditional film characters are, in this sense, brain-signs, or noo-signs.

But not all direct noo-signs of this sort are human. Deleuze describes how it is that non-human thought can be presented to us in film. In many of Kubrick’s films there are non-human actors that seem to think. For example, in The Shining, it is as if the mountains seem to think, to have an ability to process the world in a non-human manner, such that the architecture of the hotels corridors become like the twisting of the folds of a human brain. The same with the obelisk in 2001, which contains multiplicities of images inside it. These are noo-signs which are brain-signs. And the ultimately brain-sign, of course, is the cinema screen itself. This is why Deleuze says, famously, that “the brain is the screen.” For the screen is an object, a regular object, upon which many images can be projected which are then synthesized by us, this brain’s neurons. We are the neurons of the giant cinema-brain which is the screen, just as the complex of screens in the cinematic apparatus spread across the world are neurons in this larger, global cinema mediascape brain.

Exploring a giant Cine-Brain: One of Kubrick's Noosigns in 'The Shining'

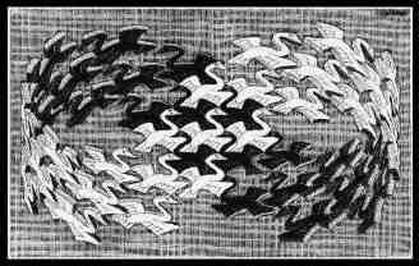

Brains are always topological, for Deleuze, and here we see an engagement with Lacan. Non-orientable figures in the mathematical discipline of topology indicate shapes that contain paradoxes within them, that make sense mathematically, and can even be sometimes physically constructed, and yet, disorient our normal sense of what it means to be a shape in some manner or other. The Moebius strip and Klein bottle are two classic examples, and Lacan uses them both pretty extensively to describe how it feels to experience time, as well as the continual whac-a-mole we play with our unconscious (basically, it is always already wherever our conscious thoughts are not).

Deleuze isn’t one to let Lacan get away with any cool insight without warping it to his own ends, exploding it from within, making it multiple. Thus, for Deleuze, a brain-image is an object which is the obverse, so to speak, of the thought which it performs. It is the container for the process of thought, and when we image it we can image either the images which produce the thought itself (ie: Godard) or the thinking object (ie: the monolith), but it is nearly impossible to image both without some sort of trick, a split screen or something to this effect. For in order to image both the thinker and thought, there would need to be a topological twist, for the two are like two sides of a Moebius strip. Certainly if one wanted to image the brain within a flow of images being synthesized by it, then it could only emerge as a stain or gap, in the manner theorized in Lacanian visual theory. For the brain is what is missing from thought, and yet also what allows it to occur. This means that the brain is closely related to the notion of the unconscious in Lacan. Deleuze works hard to show his models can do everything that Lacan’s can, but then also more.

M.C. Escher's wonderful 'Moebius Swans

loading...