|

“The cinema has always been the subject of everyday conversations and that reinforces its role as a form of ongoing, informal education” - Alain Badiou  The cinema is for Badiou one that is interested in everybody, one that welcomes regular words as much as unpretentious bits of knowledge. In the event that the reality of the matter is that, as Badiou puts it, ‘philosophy doesn’t have to produce the thinking of the work of art, because art thinks by itself’ , then what is the place of the philosopher in this school for everybody? Is it accurate to say that he is an master or a follower? Does he address or tune in? What space does the talk of reasoning case for itself after entering the school? Remarking on André Bazin, Badiou figures a vague answer by asserting that there are great and awful explanations behind reasoning's current enthusiasm for film. While both reasons propose to the possibility of the philosopher as teacher,, they don't discount the likelihood of a philosophical apprenticeship through film. The terrible reason focuses to theory's requirement for intercession. Cinema is a piece of a common affair and in this manner offers itself unequivocally as a site of arrangement. At the end of the day, film helps by deciphering the ideas logicians make and work with. Film is consequently instrumental to reasoning. The great one communicates then again, a specific need at the heart of cinema. Rationality intercedes correctly on the grounds that silver screen is presently re-characterizing its own space; film does not have its own inquiries (123). As it were, the thinker either utilizes silver screen as a site for outlines or creates the reasoning that film can't do. In both cases the logician coaches silver screen as to its own particular potential outcomes, as though movies were unknowingly giving responses to inquiries they don't get it. In the essay ‘Can a film be spoken about?’ Badiou depicts his talk as aphoristic (restricted to the undefined judgment of ordinary discussions, additionally from the diacritical one of the film analyst) which intends to talk about a film qua film, with a specific end goal to sort out one's talk around “cinema’s subtractive (or defective) relation to one or several among the other arts”. In this entry the connection amongst cinema and philosophy appears to experience a reversal: so as to talk about a film, one must comprehend it qua film, one must give the peculiarity of a film a chance to uncover itself, through takes and cuts, with a specific end goal to“maintain the movement of defection, rather than the plenitude of its support”. It is through the mindful examination of silver screen's takes and slices that film's deficient connection to painting, music and theater is uncovered. In this manner from the “discourse of the master” we have moved to the talk of the understudy. The savant's place in this school for everybody appears to be fairly questionable, a development between the instructor's work area and the understudy's seat. This accumulation is an enlightening case of how this development educates the continuous experience amongst cinema and philosophy. With a specific end goal to comprehend this experience one should along these lines be mindful from one perspective to the course of a group of stars and on the other to a progression of dreams. In the section ‘Cinema as Philosophical Experimentation’, Badiou portrays film as having an advantaged relationship to reasoning. However this relationship experiences from the onset a procedure of duplication and produces two inquiries and two methodologies: “how does philosophy regard cinema?” and “how does cinema transform philosophy?” . One ought to dependably remember that the scholar poses the question ‘how to regard cinema’ from a particular reasonable star grouping, a profoundly explained outline. This minute – which could be said to identify with Badiou's ‘bad reason’ – can never be totally stifled in light of the fact that the philosophical direction unavoidably demands (a) philosophical personality communicated from inside logic through philosophical vocabulary. At the end of the day, the star grouping must be unmistakably characterized each time rationality goes through silver screen, regardless of whether this heavenly body is confirmed, conceded or tested by film. The heavenly body delimits the parameters of the experience. In Badiou’s constellation cinema is presented as a ‘defective art’. Cinema therefore can be categorized as one of the four conditions (art, science, love, politics) that Badiou comprehends as creating truths. The philosophical errand – constantly organized around the class of truth – is along these lines that of conveying a development between the movement of contentions and the presentation of points of confinement. This development then seizes truths, logical, political, imaginative and loving ones. . Philosophy, as the realization of this development is in this way, the site of thought at which (non philosophical) truths seize us and are seized as such” and can just arrange an "objectless subject, a subject open just to the truths that travel in its seizing and by which it is seized". As art cinema is accordingly on the double logic's condition and offense, since, as Badiou states, “philosophy is always gnawed at, wounded, indented by the evental and singular character of its conditions”. The misty brightness of art crosses philosophy and seizes it, but art does not become an object for philosophy. With the term inaesthetics Badiou illuminated exactly this thought: the philosopher does not transform art into a question for logic, but rather portrays the intraphilosophical impacts of artist as “the thinking of the thought that it itself is”. It is from inside the heavenly body externally laid out here then that Badiou can comment that the " relationship between philosophy and cinema is not one of knowledge, but one of transformation”. It stays to be perceived how, from inside Badiou's constellation, cinema transforms philosophy. A to begin with, hurried answer, can be endeavored: : cinema never transforms philosophy, however constantly just a philosophical constellation; the change practiced by film on reasoning must be seen from inside a particular philosophical signal, that is from inside the specificity of a heavenly body. This is for two reasons: it is constantly through the intervention of a specific constellation (or genre, or sequence, or concept) that the experience between the two happens. The constellation is not really an appropriate name, it could rather be characterized as a solitary setup of ideas and their introduction or better as the intervention between these two minutes. This course of action delivers a peculiarity that gives importance on to the experience by deciding the whys and hows of a philosophical look on film. Cinema can therefore transform the singular constellation, the likelihood of a particular method of considering. To state, for example, that film conveys philosophy to an end, would intend to reduce once again cinema to philosophy, as though cinema could be totally consumed by philosopohy; it implies besides that from one perspective cinema satisfies its assignment by conveying philosophy to one more end, while philosophy can then start once more, by and by. The second reason is maybe all the more illuminating: to say that cinema as such transforms philosophy as such, would dependably lessen the dialog to the vitality of both, thus either would be changed into an outright that drops another supreme and its own peculiarity. In other words this would mean from one perspective to request that of cinema distinguish what is fundamental about philosophy and after that change this pith, and then again to request that philosophy recognize what is basic about film and submit itself to the change this substance can create. The question subsequently is to be placed in these terms: what can be opened by and in cinema from inside a solitary star grouping that difficulties this specific game plan? What components and works of cinema, as distinguished by a particular constellation, create onthis constellation a muddling, a deafness, a blind side, the minute where eventually very constellation that has delivered this very understanding can't be straightforwardly watched any longer. Badiou gives a case by saying that film produces new blends: “if we are able to create philosophical concepts from cinema it is by changing the old philosophical syntheses by bringing them into contact with the new cinematic synthesis” For this situation cinema changes philosophy by caving in the resistance between developed time and unadulterated span, amongst progression and brokenness.Cinema in this manner delivers new worldly combinations. It is along these lines as a philosophical circumstance that cinemacan change philosophy, by grabbing the blends logic has made and acknowledged. Badiou then advances a second argument. Cinema transforms philosophy since it opens it to a difficulty, it shows this inconceivability by exhibiting it. The inconceivability identifies with the authority of sensible limitlessness. Cinema draws in a battle with the endless and fruitful movies prevail with regards to filtering the unending, by creating effortlessness out of everything there is. Out of this vastness Cinema develops with something new, something which may seize philosophy in a way that philosophy can't yet perceive, something which is both a condition and an offense. As Badiou expresses “while philosophy involves inventing new synthesis, I think that it hasn’t completely understood cinema yet”. Maybe here dwells the reasoning of cinema: an imperviousness to be seen, hence a tutoring and a future; atruth for everybody that philosophy can't yet educate. At any rate this is the thing that Badiou appears to let us know.

0 Comments

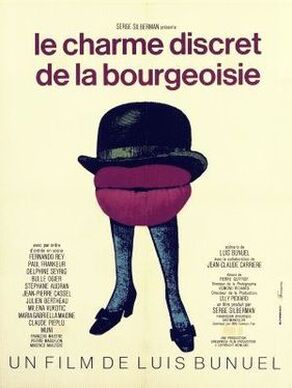

From the 'Aliens' space marine to the polygamist patriarch of 'Big Love' Regardless of whether you knew him as the "Game over, man!" snort from Aliens, the perverted more seasoned sibling of Weird Science, the polygamist patriarch on HBO's Big Love or any of his many convincing cameos or grasp supporting parts, Bill Paxton was dependably a solid nearness – a Texas-conceived utility player who could go from unpleasant to thoughtful, giggling to ethically stable in seconds level. The news of the 61-year-old on-screen character's passing toward the beginning of today filled online networking encourages with fans citing lines and namedropping their own best Paxton minutes (who knew there were such a large number of Hatfields and McCoys advocates out there?); to be honest, coming down a rundown of his most basic motion picture and TV parts to a unimportant 10 is harder than you'd might suspect. We've singled out these past huge turns, nonetheless, as our top picks of the gone-much too early star. For an era of watchers raised on John Hughes' high schooler comedies, Paxton will dependably be Chet – the group cut–sporting, shotgun-toting more established sibling from hellfire. (The way that his impermanent residency as a discharge coverdd Jabba the Hut-like animal – a definitive comeuppance when you cross Kelly LeBrock, people – appears to be less odious than the kin in his human shape says a considerable measure in regards to this character.) The performing artist as of late told WTF podcast have Marc Maron that a large number of Chet's best lines were taken from Paxton's own particular past misfortunes, including his scandalous offer to cook our saints "a nice, greasy pork sandwich served in a dirty ashtray." Paxton made such an impression as a bombastic marine in James Cameron's touchy Alien continuation that decades later, at whatever point fans discuss that motion picture, the primary thing they quote is quite often his whiny announcement: "Game over, man! Game over!" Part entertainment and part plot-driver, his Private Hudson exemplified the blend of arrogance and frenzy of a savage military compel bulling its way into an unsafe circumstance. (Any likeness to certifiable parallels amid the Reagan Era were, normally, totally incidental.) Along with Weird Science, it's one the most punctual signs that the performing artist was more than willing to put on a show of being an alpha-male jokester if the part requested it. It's likewise an extraordinary Exhibit A for what a precious troupe MVP he was. Much sooner than she turned into the main female to win the Best Director Oscar, The Hurt Locker's Kathryn Bigelow gave activity awfulness fans one of the half breed class' best films – and talented Paxton with one of his most magnificently unhinged parts. As a major aspect of a family of vampires wandering the Southwest looking for casualties, he plays the film's inhabitant batshit bloodsucker, the kind of animal of the night who likes to play with his sustenance before tearing out its jugular. No one alive or undead can tear separated a redneck bar ("I hate it when they ain't shaved") with more hero panache, or pronounce that the Type O he's recently gulped up is "finger-licki' great" with more view biting fervor. Next drink's on us, Bill. Despite the fact that he exceeded expectations in an assortment of parts all through his profession, Paxton was getting it done at whatever point he was given a role as a not-as-basic as-he-appears to be little towner. In executive Carl Franklin's relaxed, southern-singed wrongdoing picture (co-composed by Tom Epperson an as yet youngster Billy Bob Thornton), the star put a deep turn on the character of an Arkansas police boss who find out about a band of brutal medication traffickers than the LAPD analysts working on it anticipate. His neighborhood lawman – nicknamed "Hurricane" – resembles a rendition of himself: a man whose aptitudes and astuteness are disparaged in light of his thick complement, expansive grin and amiable attitude. Paxton flexed his comedic side as a supporting part in this Arnold Schwarzenegger activity flick, playing the world's most obscene utilized auto businessperson – a mustachioed crawl who's been alluring spy sequestered from everything Ahnold's significant other, Jamie Lee Curtis. In one of the motion picture's most life-changing scenes, he happily describes how he's tempted a housewife, ignorant that Schwarzenegger is the "exhausting rascal" she's married to and bragging that she has an "ass like a 10-year-old boy." (Don't even ask him why Corvettes are a two-bit Casanova's vehicle of choice.) Although he has a littler part, it prompts to an essential kicker toward the finish of the film. While Tom Hanks was showing the ethics of quiet reasonability as genuine NASA space explorer Jim Lovell, Paxton's Fred Haise was remaining in for every other person – particularly, those group of onlookers individuals who'd be significantly more bothered in the event that they were stranded in space on a breaking down module. As grouchy as he is fit, the flight's shrewd architect turns into the human face of a mission gone astray, beefing at his collaborators noticeable all around and on the ground. (And keeping in mind that as yet completing his work, in spite of battling a fever.) He's his own sort of saint, without a moment's delay a helpful person and an ornery cuss. Without a doubt, this cutting edge fiasco motion picture about runaway tornadoes (and the general population who pursue them) is some primo Hollywood cheddar – however in the event that you required verification that Paxton could pull off a lead part and also his typical MVP supporting parts, look no further. As one portion of a storm–hunting couple gunning for some outrageous common calamities – and whose marriage is its own particular sort of shitstorm – the performing artist gives his scenes with costar Helen Hunt a feeling of battered mankind in the midst of the screeching guitar soundtrack and watch-out-for-that-flying-dairy animals set pieces. Paxton is the establishing power in a motion picture that is about grabbing garbage and throwing it through the air. He makes the sound and anger imply something. Paxton re-cooperated with his One False Move co-star Billy Bob Thornton for director Sam Raimi's astounding, underrated adjustment of Scott B. Smith's acclaimed thriller novel. In spite of the fact that they were playing Minnesotans rather than Southerners, the on-screen characters drew on their normal center American roots to convey life to the parts of two common laborers siblings who bumble onto a dead body – and a huge number of dollars. Paxton's Hank Mitchell is the more intelligent of the two kin, and the one with the more grounded inner voice, making this another impeccable part for him: a discreetly not too bad man of activity whose weaved forehead and insightful gaze uncover each stress and figuring. More individuals presumably got Paxton's Titanic turn (he's the contemporary fortune seeker who sets up the stretched out flashback to that critical voyage) in a solitary 1997 end of the week than saw his directorial make a big appearance amid the last's whole showy run. Be that as it may, his execution in this nerve-clanking outside the box thriller, about an adoring father who trusts God has charged him to wind up distinctly an avenging blessed messenger, is much more basic – and a practice in noble religious devotion run amuck. This is not your regular serial executioner, but rather a man who believes he's doing the Lord's work by dispatching miscreants, and who believes he's shielding his kids from Satan's grip each time he swings his hatchet. Given the film's multifaceted emotional, you wished he worked behind the camera more than he. Given the savagery with which he played this preposterous character, you wish Paxton's patriarchal insane person didn't frequent your fantasies to such an extent. One of Paxton's most perplexing parts, the patriarchal polygamist in HBO's distinction show discovered him straddling the holy and the debase – a banned Mormon endeavoring to steerage a business and keep running for open office while keeping his three spouses and dim past a mystery. The on-screen character assumed the part with incapacitating sympathy more than five seasons; he could both pitch you on his dedication to his confidence (and his supersized family) and make you feel frustrated about him as the arrangement heaved toward its heartrending finale. Bunuel's masterpiece "The Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie" generally is considered a surrealist film - however, it seems that compared to the "Andalusian Dog", on which, as already known Buñuel worked with Dali, "The Discreet Charm" slightly deviates from the "typical "surrealistic forms (although surrealism difficult to attribute any typical and strictly defined form), or from what mainly distinguishes Surrealism. Andre Breton's "Surrealist Manifesto" Surrealism defined, among other things, as a free psychic automatism which aims to express the actual functioning of thought. Dictation of thought in the absence of any control of reason, beyond all aesthetic and moral attitudes. " Two important factors are "the omnipotence of dream" and "disinterested play of thought." Although at first glance seems to be "discreet charm" fits in Breton's definition because of the element of dream and absurd situations that appear to be the product of anything else apart from the "disinterested play of thought," can not but let us not make that movie though something more than playing with surrealist sense. In the foreground of the film is an absurd situation that a group of wealthy bourgeois persistently interfere in order to have dinner, starting from the first scenes of the film. For these situations there is simply no adequate explanation - each of the following is more absurd than the last, and no matter how hard you try to find an explanation or meaning in each particular situation, it seems that there is not. They all look like raids, penetrating into finely decorated social groups bourgeois world - and it's dinner as a special form of the ceremony in the high society of the highest expression of this regulation, this well-structured order. They were the two main features of absurd situations - their individual unsubstantiality or inability to find their meaning in themselves, and in a well-decorated intrusiveness order - what an absurd situation constituted as Lacanian Real, as opposed to the Imaginary and the Symbolic, where all three elements of the structure of reality from the perspective of Lacanian psychoanalysis. The text will try to constitutes this situation as real and that they, therefore, to find a place in the "reality" of the film. In addition, the film was a critical and ideological character dinners, taking into account the role of dinners in the life of the privileged class as a moment in which not only displays the grandeur of their privilege, but comes to manifestations of social identity that members of this class of share. However, under that identity, under this social mask, persona in the classical sense, there is another identity that is revealed only when their holders find themselves in absurd situations. Finally, the theme of dreams is unavoidable here, as well as their role in the life of this group of the bourgeoisie. So absurd situations such incursions Real, ideological character dinners and meaning of dreams are the three main points. "What is this supposed to mean?" The question that Francois Teven sets several times during the film, and the absurd situations - "What is that supposed to mean?" Or more precisely "what is the meaning of this?" - But highlights the city absurd situations in the film. The issue was first raised when a group of bourgeois, led Tevenoom, arrives at the home of Sénéchal at a dinner, but it turns out that the dinner arranged for the next day, although the ambassador Acosta convinced that the call was for tonight - here comes first absurdity, the first conflict between what is Acosta heard and what "is". Already we see that bourgeois act a little confused - they wonder why that is not set, but it has been eight; not sure whether to completely abandon the deal or to go to another place etc.. The unusual situation in which they find themselves violates their established relationships and behaviors, plans and arrangements, the only hint of the basic characteristics of absurd situations. Then they all head to the restaurant, but found that the restaurant owner had died and that his body inside the coffin, is located in the main room restaurant, but, despite that, the restaurant staff is willing to serve them, and the maitre their promises and excellent dinner , regardless of what is dead in the same room, although hidden from the eyes of the bourgeoisie screen. And here are the modes of conduct interfere unexpected inconveniences. The question is, why this situation is called absurd, inexplicable? In the case of a dead man in a restaurant, dotted with questions: where did it here, why funeral service did not come by his body, why the restaurant is open despite the unfortunate event? This question has no answer because the question itself is absurd, or at least no meaningful response. If we try to find him, it will be impossible and we will wrist in unsolvable contradictions. Similarly with subsequent situations - for example, the shortage of tea, coffee and milk in the cafe or by entering the military battalion in the house of Sénéchal, moment after dinner finally started or else the situation in which Teven finds his wife with Acosta. And there is a lower common questions that point to the absurdity and the inherent inability to sense and, so to speak, the logical answer: how is it that no tea, coffee and milk? How to guests whether all this go away? Or, what kind of military maneuvers taking place in the middle of France? What is the custom to colonel with the whole troop come over for dinner? Or: how to Teven so coolly and calmly react to the fact that his wife was with Acosta and goes to the waiting at the car? How so easily accept the excuse that if what he wants to show her "sursicks", although it does not exist? Take this inherent impossibility of meaningful, logical answer? What is essentially an attempt to respond to this question, attempts to find meaning in these intrusions? This question is, in contrast, can be answered, but to do that, is going to report on a three-part structure of reality from Lacanian perspective - the division of the imaginary, symbolic and real terms. This division is best illustrated by the example of any board game: the symbolic element of the structure of reality that demands to be rules, but the rules in general, not specific rules x or y (for that level will ensure symbolic, as will be discussed later). In this sense, the symbolic determines form, giving a form that must form the rules, whatever those rules - symbolic meets form content, specific rules x or y - that is, in the case of social games, the symbolic arrangement requires rules. Imaginary here are the names of figures and their physical form, but not only that - if we symbolically designated as an abstract form of rules, Imaginary for the content in all its forms. It is easy to imagine a game where there is regulation of the rules, but all the facilities replaced in relation to the previous content. Finally, the real is contingent here (on this I'll be back a little later) - Intelligence toy or some event that could disrupt the game or that is completely interrupted, therefore, something that does not belong to the symbolic order, but it is not imaginary. More abstract terms, the symbolic order of the reality which is symbolized, in which "everything has its place" in order and nothing he does not avoid, and where things through the mechanisms of the signifier and the signified caught in symbole network operators which govern your reality. Symbolic is primarily, but not only, linguistic categories, a question of language. The symbolic order consists of rules, and those who are aware of and which have not, and that we have to follow (just like the rules in board games) that we could not communicate with others, and that through this communication constitute as subjects (again, as as the figures in the social games constituted through rules). It is obvious that communication and communication rules represent something that is like a second nature for all of us, something without which we can not - in other words, and we are caught in the symbolic network, as well as all the other things that we accommodate. Ranking the "big Other" - it seems like we are, because we have to obey the rules in order to be recognized as entities subordinate to an agent that controls our actions. In the sense in which we determined that, we - the symbolic order as a great companion, which can be embodied, eg., In a God who sees everything and control everything. What is the difference between the symbolic and the symbolic, given that these two terms sound similar? Here is an interesting phenomenon first bishop in the film, which comes with Senshel's to become their gardener. Apart from the possible interpretation of subordination of the Church's most powerful, highest class, where it serves only to hoe the garden and take care of the lawn prosperous capitalist property, or capitalist order, not mired in the weeds and thorns, and the "immorality and sin," Bishop Bishop by symbolization, or symbolization, which is different from the symbolic order that we talked about earlier. While symbolic order includes symbols that are associated only with other symbols (requires an abstract form), symbolization of which we are talking, which is symbolic, in connection with the matters. Both bishops constituted his church robes and a cross around his neck - the time in which it appears in gardening overalls, Mr. Senechal roughly ejected from the house, but when he returns to his "law suit", recognizing him as a priest, although it comes a man of the same physical appearance. In this sense, one could say that the priest is not a priest because he has some essential traits that define him as a priest, but because it is so recognized by other entities. Hypothetically, if all operators stopped priestly robes recognized as belonging to the ranks of the Church, the priest is no longer a priest. In the film clearly "see" all three elements of the structure of reality - Symbolic are the rules by which the bourgeois behavior, their fine manners and etiquette, knowledge of food and drink and the ways in which they are most delicious, "most appropriate" consume, unlike simple consumption (what we see at Akostinog chauffeur); The symbol is also a place occupied in society - Acosta's ambassador, Sénéchal women's - free - Sénéchal women, Teven and Senechal are wealthy businessmen and so on. When not acting according to prescribed rules and not occupied and social functions, would not be what they are. On the other hand, their names, history, physical appearance or tone of voice that are imaginary, and we could imagine that they look completely different and have different names, but to again be a group of the bourgeoisie which has been trying to dinner but she does not succeed. However, Imaginary is not accidental, not arbitrarily, but, structurally speaking, determined Symbolic. What is the role of the Real in all this? Similar to absurd situations in the film is realistic, so to say, inexplicably, elusive, something that escapes symbolization and placement in the symbolic order - as absurd situation can not explain and elude placement in the "sense", as when Teven asks " what is the meaning of this? "but does not get the answer - but what is traumatic remainder, a surplus that could be symbolized. Lacan calls it Things, with a capital "T", but not in the sense in which it is Kantian thing-in-itself, transcendental, inaccessible to reason, devoid of attributes, non-produced, and on the other side of reality available to us. Realistically not something external symbolic order which is substantial and there is a positive, a tangible thing, but is in the middle of the order - what is his lack, it is also redundant in the sense that eludes symbolization, and lack of, in the sense that it is the result of incoherence , imperfections and shortcomings of the order itself. So real terms at the same time and produces or is produced - not only disturbs the symbolic order of the entries mentioned inconsistencies, irregularities and conflicts in it, but is the product of precisely these irregularities and conflicts, or the inability of symbolization. On this track, Realistically it could be qualified as "ekstimate" - external intimate - in the sense that the outside but it is also there, in a way, either here or there, it just adds explainable and the fleeting nature of the Real. This directly follows from a better perspective on the absurd situations. Although the situation is definitely absurd and have no explanation, do not fall from the sky and do not represent a "miracle" - not, each of these situations is produced by irregularities and cracks in the symbolic order: for example, a military troop that decline in house of Senechal (and while the use of marijuana, which only seems absurd thing) is that due to the maneuver being performed (which can not be represented as a gap in the standings after military exercises in the city are not usually part of the order) and also gets produced from incoherence in the symbolic order. At the same time, they distort reality Symbol subjects and also produced a series of consequences where do their decline (ie, where Realistically exercise its decline) - bourgeois again I can not have dinner because of the military or the mysterious disappearance Sénéchal's makes the brain because they think that the issue of police raids, thereby effectively abyssal yourself a chance for lunch. Thus, the ratio of the Real and Symbolic dialectical relationship - is realistic product Symbolic, because the very system deficiency causes the symbolization of the Real, but also causes symbolic because in turn becomes the cause of the failures. It should be noted another aspect of the absence of the Real - it does not have to happen, does not have to have it in any way other than as a cause of disorder in order. Like the traumatic event that is identified as traumatic only when the recognize as the cause of symptoms, Realistic retroactively recognized as real terms after distortion or repetition (such as repeated failure Dining) which entered into the symbolic order. So in the film, the situation does not define itself - we recognize them as absurd, and Lacanian Real, only the consequences they have. If we Realistically constituted at the same time as the deficit and as a surplus, it can not be without being reminded of the objet petit a: the same as real terms does not have to exist that would have consequences that would be effective, and objet petit a no, it is the lack, gaps in the symbolic order, a gap in which the symbolization missed. At the same time, it is a surplus, and this surplus jouissance. If we put an equal sign between the real and the absurd, it becomes clear that only the theory that handles concepts such as Real, objet petit and jousissance, the terms of which both are and are not, which are inherent to the seemingly absurd construction can adequately analyze and deal with absurd situations - but not so that it creates a new absurdity, as in the movie, but one gets a different kind of rationality. This is not a positivist rationality, which handles the formulas A = A and not-A = non-A, but dialectical rationality in which opposites pervade, whose elementary particles can not be reduced to mere identity to themselves and whose terms condition each other in seemingly, and only seemingly absurd circle. Cooking and ideology Since we founded explained the functioning of symbolic order, it is obvious that evening (taken in a broad sense, as ritual meals) has a very important place in the standings. It is no coincidence that just the bourgeoisie tries to dinner throughout the film - in the life of the upper classes, dinner is never just dinner. There is something about her which gives it special importance. When the bourgeoisie dinner, the food itself is not important - it's an opportunity to talk about many things more lucrative, business, political events, etc. The food here can also be viewed as a fetish - as a material object which itself is not essential and can take different form, but it is important what is '' behind the building, "a kind of" aura "that fetishized object possesses and that is actually what what is important, what interested fetishists - in this case, the bourgeoisie. Here it is advisable to refer to Levi-Strauss' semiotic triangle of food, or three ways of preparing food, which indicate the relationship between nature and culture: raw food as what it signifies nature, baked like what signifies culture and civilization, and cooked as a mediator between the two opposites. The whole attitude indicates opposition of nature and culture, nature and civilization, and nature as a non-produced and history as produced, in a certain sense. Since the relationship of nature and history of the subject almost every ideology (especially philosophy as the highest form of ideology, to use the words of Marx), we can conclude that every breakfast, every lunch and every evening a matter of ideology, that this rite, neatly placed in a symbolic order, by no means an ordinary, everyday thing. In this regard, when the bourgeoisie sit at the table to dine, then it enjoys one bourgeois meal that was knee-deep in ideology. The question is: where ideology? If you continue to follow Marx and confirm that the ruling ideas of a society in a period of ideas of its ruling class, it is clear that the dinner to his knees in the ruling ideology. Dinner has its own rules, and in this regard is entirely located within the symbolic order. Do not acquire you that impression directly from the film? When our group of bourgeois sits at the table, it selects with taste, very select field in an appropriate manner; When drinking a martini, drink it mouthful by mouthful, as appropriate. As I mentioned, Akostin chauffeur it works in a different way, and there we can see hints of class differences and class conflict that later justify the words of Ms. Senechal - "he is plain, uneducated man." In other words, in order to properly consume food and drink, it is education or treatment and lifestyle reserved only for the privileged. This dinner has the character of a ritual with clearly stipulated provisions, almost like a ceremony - for this purpose, it is interesting that the restaurant where the dead man's name "La sabretache", a word denotes a piece of uniform cavalry officer from Napoleon's time, as we can not recall nothing else except the ceremonially, solemnity. We can imagine that the bourgeois meet regularly in an attempt to have dinner and it becomes a kind of tradition, a tradition appears where there is a lack of institutions, the absence of legal regulation. Rituals are an attempt to compensate for the imperfections of this - as in the former Soviet bloc countries, and even here, where after the collapse of the institutions for the sake of the free flow of capital refreshed rituals - religious, secular, personal, etc. Not a movie, not far from that association - corruption Ambassador Acosta and his accomplices in the drug smuggling implies the absence of regulation, as well as military exercises in the middle of town, with the army that uninvited intrusion into the house, pushing free smoking marijuana. To this end, the bourgeoisie are trying to provide our rituals, here specifically ritual dinners, replacing the absence of institutions and defend their orderly lives from the onslaught of deregulation. As rituals and ideology are concerned, it is interesting to craft that Bunuel says in his film Phantom of Liberty, where guests sit at a table on the toilet seat, water pleasant, friendly conversation, and when they want to eat, ask the host for ''one room". In the same way, and contrary to the food industry is very ideological, which confirms that the symbolic order governs all that is like '' second nature '' entities, and to entities constituted within the system and through the order. Turning now to fetishism dinner. Fetish rule used to be the lack of compensation, something that is not there - it is a constant search for the true object of desire for objects that will never be able to be sustained. This begs the question is not: if a fetish used to cover a shortage, then he conceals the lack of - what? When played incursions in Real, when coming to the fore the cracks and incoherence in the symbolic order, and comes to cracks and incoherence in the Symbol in relation to the bourgeoisie - a fine, exemplary subjects of civil society bourgeois become confused, rejected their manners and behave differently than before. Maybe just this hides discreet charm of the bourgeoisie - must charm us with its ability to be indiscreet and inappropriate to pull out of every uncomfortable situation that would then regained her composure and continued business as usual - a discreet and appropriate. And just when we think, in the scene where the house fall into armed terrorists, that the bourgeoisie is over and that this time will not be able to avoid a dangerous encounter with the Real, it turns out that it was Akost's dream, after which everything returns to normal. Here we try to apply the concept of persona in the ancient sense. In ancient times, the term described the social role that the individual took on themselves; Eventually the term began to mean personality, personality, uniqueness and singularity of each of us, that is. person, how to read a literal translation. From the identification of social roles, the term began to mean a particular kind of individuality that came to the fore during the rise of the bourgeoisie of the city's ruling class. However, if we revive the notion of persona in the classic sense, we can say that during the intrusion of the Real in the symbolic order, the bourgeoisie is one of the mask of social roles and below it to see their "true essence" - hypocrisy, selfishness, greed (for example, when trying to Acosta grab a piece of meat off the table during the incursion of armed men) and so on. However, this is a false trail, because under the mask reveals positive existence, it is revealed that there is something which is in direct contradiction with the position that the bourgeois are trying to have dinner because dinner fetish that hides lack, because here reveals that there is no shortage. What's this about? As bourgeois as individuals are concerned, their change of behavior does not reveal anything to the incoherence in the symbolic order. However, a shortage remains. Fetish serves to mask the lack of - fetish is always a substitute for the original object of desire that is lost and that can not be undone, but despite this, the desire is not slowing down, and the search for the object of desire continues, as stated above. Therefore, bourgeois and persistently trying to have dinner, because they stimulate the desire for (unreachable) object of desire. However, dinner was impossible - the very cracks in the symbolic order creating the Real incursions and therefore, hypothetically, if the bourgeois attempt to dinner a hundred times, it'll be a hundred absurd situations. This can only mean one thing - that the lack of a fetish conceals a lack in the symbolic order, the lack of inherent order and that we fetish try to "forget" that the symbolic lack flawed. This dinner becomes a vicious circle - it is impossible, but it does not prevent the bourgeoisie to try to have dinner. In other words, a fetish is T or signifier missing in the Other, the signifier is not in the symbolic order, ie. the Big Other. He is also a signifier of objet petit a, the lack, gaps in the symbolic order. It is this lack of what products Real, it produces absurd; at the same time, real production shortfall, absurd produces its own inability to "de-absurdisation'' - more precisely, absurdity itself prevents the elimination of over symbolic order. The absurdity is necessary - the bourgeoisie can not be without it. In this way, it seems that the persistence with which the bourgeoisie try to have dinner in conjunction with its charming art of escape from every unpleasant situations - if the absurd is necessary, then it is necessary and this indiscreet charm of the draw from the situation; paradoxically, that would occur each subsequent absurdity, it is necessary that the bourgeoisie be able to return to the old, and they are able to do thanks to the indestructible Real that again and again penetrates the symbolic order. Symbolism of dreams Finally, it should take up the theme of dreams prevailing in, tentatively speaking, the second part of the film. The theme of dreams is not rare in surrealism and Buñuel her here dedicated due attention. Although it seems that dreams are meaningless as absurd situation, if there then the current line of thinking, we will see that the film has here a lot to tell us. The most interesting is the dream of Mr. Sénéchal, which is really a "dream within a dream" who dreaming Teven. The first thing we can observe is that Sénéchal's dream expresses fear of the bourgeoisie to be uncovered - even the food, the fetish, false because the butler on the floor turns out artificial chicken - in his final intentions and scams perpetrated over their "friends". When you raise a theater curtain and terminate them (again) in the evening, the most impressive moment is that when whisper tells them text to excuses. Prompter just plays the role of the big Other, symbolic order, which subjects what to say and what to do; On the other hand, the audience at the same time plays the role of the big Other - it is like a criteria before which we have to prove or experience the shame. Is not Sénéchal reaction - sweating, and confusion or fear of power at a deeper level - exactly what would happen to us tomorrow if we suddenly forgotten the language we speak and were disabled to communicate with others within the system? When individual bourgeois begin to leave and refuse to fulfill the assigned role, the public disapproves and rejects them - that are possible given a role in the symbolic order, we would have been rejected. If that were to happen, we ceased to be subjects - in other words, we ceased to be human. However, the embodiment of the second points to another feature of symbolic order - his vulnerability. The moment Other stops working through symbols, through words and control words and communication, but takes physical form, reminiscent of the spirit that takes the body - then the spirit bar can attack, if not destroyed. A good example of this is the recent revolution in Egypt - the moment when the government ceased to manage symbols and when she reached for individuals or for weapons and physical force, repression, gave a clear signal that it is in crisis. On the other hand, when the order of the hotel, can serve as a right-wing Jew fetishization (or Arab, black person, etc.) Who pulls all the strings and managed entities, because right-wingers of all backgrounds can not see the structure, they see relationships and connections, but the body they can point a finger. However, with regard to Surrealism and psychoanalysis, wants to talk about what is not allowed to talk, he wants to talk about the reasons due to which someone does not want to talk about the forbidden and that, in the indicated terms, Bunuel's film carries a subversive message, legitimate the right to write off this attempt fetishization. The right-wingers, in the case of forbidden speech, they do not want to talk about it, because it is important to maintain order, not to enter the confusion - in a sense, not create absurd, and we have already said that psychoanalytic theory only can analyze absurd, given that itself handled the seemingly absurd notions. After Senechal wakes, they goes to the gathering at the Colonel. It is immediately clear that the ambassador Acosta does not fit the environment, to the extent that the provocation Colonel responds by firing a pistol, killing the colonel. Soon after, it is revealed that Teven all dreamed of, even Senechal dream. What does this tell us? First, to Teven care that Acosta violently react and compromise himself, Senechal and the Teven and threaten drug trafficking which involves, what would they ruin everything. On the other hand, we can once again get back to the symbolic order and Real. If the army is understood as a reality, which is in accordance with absurd situations that we saw before the break, as something that is done intrusion in the symbolic order of the bourgeoisie, which is rich in rituals and traditions, we can say that the colonel as the embodiment of the military poses a threat to this order, which is why Acosta ventured the murder. The ratio of the Real and symbolic order remains the same as before - the internal contradictions of bourgeois society, and class antagonisms, themselves born army and militarism in general. Historically, the army was not afraid of coups and rebellions-translated from the language of Marxism to psychoanalysis, the contradictions of bourgeois society are cracks symbolic order that are born army that is Real and, from time to time, perform intrusion in order. On the other hand, the army maintains bourgeois society, and thus its contradictions, so again drawing the vicious circle of the Real and Symbolic. Source: Filmske radosti | Filmovi koji nas gledaju Author: Vuk Vukovic Translated by Dejan Stojkovski

I already am eating from the trashcan all the time. The name of this trashcan is ideology. The material force of ideology makes me not see what I am effectively eating. It’s not only our reality which enslaves us. The tragedy of our predicament when we are within ideology is that when we think that we escape it into our dreams, at that point we are within ideology.

They Live from 1988 is definitely one of the forgotten masterpieces of the Hollywood left. It tells the story of John Nada. Nada, of course, in Spanish means nothing. A pure subject, deprived of all substantial content. A homeless worker in L.A. who, drifting around one day enters into an abandoned Church and finds there a strange box full of sunglasses. And when he put one of them on walking along the L.A. Streets he discovers something weird; that these glasses function like critique of ideology glasses. They allow you to see the real message beneath all the propaganda, publicity, posters and so on. You see a large publicity board telling you have a holiday of a lifetime and when you put the glasses on you see just on the white background; a grey inscription. We live, so we are told, in a post-ideological society. We are interpolated, that is to say, addressed by social authority not as subjects who should do their duty, sacrifice themselves, but subjects of pleasures. ‘Realise your true potential. Be yourself. Lead a satisfying life.’ When you put the glasses on you see dictatorship in democracy. It’s the invisible order, which sustains your apparent freedom. The explanation for the existence of these strange ideology glasses is the stand-up story of the invasion of the body snatchers. Humanity is already under the control of aliens. "Hey buddy, you gonna pay for that or what? Look Buddy, I don’t want no hassle today; you either pay for it or put it back." According to our common sense, we think that ideology is something blurring, confusing our straight view. Ideology should be glasses, which distort our view, and the critique of ideology should be the opposite like you take off the glasses so that you can finally see the way things really are. This precisely and here, the pessimism of the film, of They Live, is well justified, this precisely is the ultimate illusion: ideology is not simply imposed on ourselves. Ideology is our spontaneous relation to our social world, how we perceive each meaning and so on and so on. We, in a way, enjoy our ideology.

loading...

To step out of ideology, it hurts. It’s a painful experience. You must force yourself to do it. This is rendered in a wonderful way with a further scene in the film where John Nada tried to force his best friend John Armitage to also put the glasses on.

I don’t wanna fight ya.

I don’t wanna fight ya. Stop it No!

It’s the weirdest scene in the film. The fight is eight, nine minutes…

"Put on the glasses."

…It may appear irrational cause why does this guy reject so violently to put the glasses on? It is as if he is well aware that spontaneously he lives in a lie that the glasses will make him see the truth but that this truth can be painful. It can shatter many of your illusions.

This is a paradox we have to accept. Put the glasses on! Put em on! The extreme violence of liberation. You must be forced to be free. If you trust simply your spontaneous sense of well being for whatever you will never get free. Freedom hurts.

loading...