NINA POWER revisits five radical, mixed-genre films from 1965–74 that explore sex and revolutionDUŠAN MAKAVEJEV - Mysteries of the Organism SEXPOL AND INTERNATIONAL CONTROVERSY, 1971–74Regardless of the uniqueness and beauty of Makavejev’s earlier features, it is with WR that his reputation will stand and fall. Not quite banned, but not available either in Yugoslavia for sixteen years after it was made—“just not allowed,” as Makavejev puts it in interviews—the film is an explosive and ambitious mix of Makavejev’s earlier obsessions: sex and politics. But it has an international dimension that seeks to address not only repressive forms of social organization but also the dangers of freedom, or at least of the kinds of freedom that twentieth-century America sought to define itself by and against. It is no surprise that many have related Maka vejev’s work in this period to Herbert Marcuse’s thesis in OneDimensional Man (1964) that the supposed freedoms of capitalist choice are only more efficient ways of tightening the shackles of control. Far from being a straightforward celebration of sexual liberation as a superficial reading of the film might indicate, WR is in part about the dangerous effects of desire when the latter is—to use the terminology of Deleuze and Guattari once more—“deterritorialized” too quickly. (If you break an egg, it is useful to work out where the inside might land, for fear of soiling your clothes . . .) We have seen in the decades after Makavejev’s film how capitalism is faster and more efficient than other systems at recapturing desire for its own ends: WR can, in this sense, be read as a warning during a cultural cold war in which the opponents vie for hegemony over human passions. But it is also a film about the inherent unfairness or injustice of desire, regardless of political systems. One may very well want to “fuck freely” in the name of an egalitarian politics as the narrator implores, but there are some people that everyone wants and others whom no one wants at all. A politics based on desire will be unfair. WR caused a riot; how could it not? One of the outcries, oddly enough, was over Makavejev’s representation of Wil helm Reich, the unofficial hero of the film. In The New York Times (November 7, 1971), David Bienstock, then Curator of Film at the Whitney Museum of American Art, accused Makavejev of misrepresenting the teachings of Reich: “while Makavejev, on the surface, seems to be praising Reich, the actual content of the film mocks and maligns him. Makavejev then cloaks these distortions in a web of comedy and ‘avant garde’ ambiguity. It is an old trick. Hide the poison in sugar.” Bienstock’s irritation at Makavejev’s “misinterpretation” of Reich unwittingly reveals something about the filmmaker’s strategy, however: “hiding the poison in sugar” will actually form one of the central images of Sweet Movie a few years later; as the revolutionary Anna Planeta kills a renegade sailor from the battleship Potemkin, the blood from his stab wound taints their shared bed which is, absurdly, entirely made of white sugar. Makavejev is a master at mixing materials: the clean with the dirty, the sweet with the deadly. WR: MYSTERIES OF THE ORGANISM: THE BATTLE FOR DESIRE© 1971 Dušan Makavejev. DVD: Criterion Collection. WR is an astonishing fusion of interviews, found footage, propaganda, fictionalized accounts of the encounters between Yugoslav women and an invented Soviet hero, parodies of political speeches, and a vision of an America dangerously unable to cope with its own desires. It is at once a celebration of Reich’s insights (you can read the “WR” of the title as both Reich’s initials and “World Revolution”) and a critique of the commodification of sexuality, whether it be under capitalism, fascism, or communism. The Fugs’ song “Kill For Peace” accompanies Tuli Kupferberg from the band as he wonders around New York, dressed in combat gear, caressing and masturbating a gun and frightening businessmen. Cameos by Jackie Curtis, the glam transvestite from the Theater of the Ridiculous and sculptress Nancy Godfrey, who takes a penis plaster cast of the editor-in-chief of Screw magazine, Jim Buckley, all contribute to the idea that “confusion is sex” as Sonic Youth would later put it. Nevertheless, the Yugoslav storyline involving Milena (Milena Dravi´c), Jagoda (Jagoda Kaloper), and Ljuba (Miodrag Andri´c) is perhaps the strongest part of the film—part joyful passion, part ambiguous take-up of the gestures of propaganda in the service of a sexual revolution, as when Milena, dressed half in military gear and half in her nightie, delivers an agitprop speech from the balcony of the tenement building to the proletarian masses below. “Socialism must not exclude human sensual pleasure from its program!” she declares, as a deranged ex-boyfriend chases her precisely for this very same sensual pleasure. Her eventual death, following an orgiastic encounter with a Soviet ice-skating champion who can’t handle the unleashing of pleasure that Milena induces, is vicious, but strangely in keeping with the excessive nature of the film as a whole: the Soviet Union can’t accept a different kind of socialism, its men can’t accept a different kind of woman. Milena’s decapitated head lives on in the clinical setting of the morgue, carry ing on her defence of revolutionary lovemaking. In recent interviews, included on the DVDs, Makavejev has spoken about current sexual liberation being only “freedom to discharge ourselves as machines.” Characters such as Milena represent a perhaps impossible alternative: a revolution in permanent movement rather than the “frozen” ones of Mao or Stalin, where political energy gets locked into fixed institutions and new forms of moralism. Makavejev stages the difficult moment between repression and liberation: what results is not the hippie fantasy of free, warmly expressed desire but a kind of dangerously overly emotive state, all too easily captured by cults of personality, groupthink, and fascism. “Can we organize liberation step-by-step?” Makavejev asks in one interview, mourning the all-too-quick slippage from repression to release to commodification. But it was WR that saw it coming all along. With Sweet Movie, Makavejev deliberately forgets his step-by-step idea of liberation and opts instead for a study in revulsion, bodily and conceptual. The major sensation conjured up by Sweet Movie is disgust, and there are parallels with the work of the contemporary artist Paul McCarthy, a reveling in a combination of cultural nausea and sickness of a more visceral, immediate kind. Makavejev’s characters are murderers, seducers, chat-show hosts, gynecologists, capitalists, and renegades from revolutionary eras. But the true stars of the film are the myriad substances that seep from the lens in hyperreal color: blood, shit, breast milk, food, chocolate. If Sweet Movie is, as Makavejev describes it in one of the DVD interviews, “a love letter to Kodak,” it’s a love letter one might handle rather gingerly, for fear of contamination. The objects of his scorn remain much the same as in earlier films: the cheapness of capitalism, the deadly pomposity of ossified political systems, but the tone has changed. What was once a joyful and multidimensional act—sex—is now merely a commodity to be won on a TV show. Women are to be dumped in suitcases and smeared in chocolate. With Sweet Movie one is left with the unnerving question, has the whole world become horrible? A rubbish dump of ideas and useless substances? Did Makavejev give up on thinking that there might be another way out? Against the grain of the film, some have tried to excavate an optimism from Makavejev’s most deliberately unpleasant work: for Stanley Cavell, in an essay included with the DVD, Sweet Movie “attempts to extract hope . . . from the very fact that we are capable of disgust at the world.” Perhaps this is so, but it is a very different kind of hope than that hinted at by Makavejev’s films a decade before. It is relatively easy to see the film as a pessimistic response to the assimilation of the very things, freedom and sexuality, that Makavejev sought to explore so boldly, yet subtly, in his earlier films. © 1974 Dušan Makavejev. DVD: Criterion Collection. Again the film was met in the first place by a combination of repulsion and bafflement, and these remain the overwhelming responses to this day, legally and aesthetically. As Vincent Canby writing in The New York Times at around the film’s release (October 10, 1975), put it: “it is, I think, supposed to be an erotic political comedy, which may be a contra diction in terms.” Of course, he could have been talking about almost any of Makavejev’s output here, but the fact remains that Sweet Movie is an extraordinarily difficult film to like or enjoy: the scenes with members of Otto Muehl’s commune in which they vomit on one another, rub excrement into each others’ chests, make out while covered in food, and generally howl much like Lars von Trier’s “idiots” will do many years later, is undeniably unpleasant, unaestheticized, and luridly shot. But perhaps this is the point. The film’s attack on American puritanism and crassness, as captured in the gynecological beauty show that opens the film, is undeniably heavy-handed. The utterly idiotic and money-centric Mr Kapital (John Vernon) wins the prize girl, a virginal Miss Canada (Carole Laure) whom he later daubs with alcohol to clean her before thrusting his golden penis, which shoots out clear water in her general direction. Understandably, she freaks out, and attempts to run away, leading to a series of encounters with male sexual stereotypes (the wellhung black man, the macho Latino romancer). She winds up in a daze at a commune with Otto Muehl and his merry band where she mostly refuses to play along, pausing only to suckle on some breast milk or gently caress a flaccid penis—but it’s not clear that Laure is acting her disturbance in these scenes, which only adds to the discomfort. Meanwhile, Anna Planeta (Anna Prucnal) is merrily sailing the canals of Amsterdam in a boat called Survival. The vessel happens to be filled with sweets and sugar, which assist in her seduction of several male children and of a leftover sailor from Potemkin (Pierre Clémenti). While there are moments of real joy and celebration in Sweet Movie, the overriding feeling is one of “toomuchness.” This applies particularly to the spliced-in Nazi footage of the Katyn massacre, the mass murder of thousands of Polish military officers, policemen, intellectuals, and civilian prisoners of war by the Soviet NKVD, which was only admitted by Russia recently (the incident is also the subject of Katyn, Andrzej Wajda’s 2008 film). The corpses of the Polish officers receive an odd mirroring at the end of the film where all of Anna’s lovers are laid out on the banks of the canal, emerging from their cocoons as not quite lifeless after all. The juxtaposition of images again has the disturbing effect of feeling a little too much, not right at all: if this was the effect Makavejev was after then he succeeded in spades, but it is difficult to isolate a notion of hope amid all the various minor and world-historical horrors that Makavejev parades before us. Perhaps because of the distaste and scandal generated by Sweet Movie, Makavejev’s star began to wane rather earlier than might have been expected of someone capable of making at least the first four of these re-releases. He has struggled to get funding, although he has made several notable films since the mid-1970s. But his output from the mid-60s to the mid-70s remains fundamental to an understanding of European cinema, and, beyond that, to the now closed-off possibilities of other ways of conceiving sex, politics, and film itself. Makavejev’s vision of a republic of free love, albeit a free love that understands the dangers of letting go too quickly, is both a celebration and a warning. It would be tempting to believe that we have outgrown Makavejev, that we belong to a time where sex has very little to do with politics, and cinema has very little to do with either, except as titillation in both cases (recent attempts to depict “politics,” such as Uli Edel’s The Baader Meinhof Complex is as pornographic as anything found on a seedy Internet portal). If Makavejev leaves us discomforted, we should recognize this uneasiness as the reminder of what has been misplaced and forgotten in the decades separating us from his major works. However, we would do well to remain open to both the spirit and the specifics of these ruminations on love and politics, for if they have no part to play, then things may be even worse than we imagine. NINA POWER is the author of One Dimensional Woman (Zero books, 2009), a critique of contemporary feminism. ABSTRACT reconsideration of the fruitful 1965–75 period in Yugoslav director Dušan Makavejev’s career, arguing that Man Is Not a Bird, Love Affair, or The Case of the Missing Switchboard Operator, Innocence Unprotected, WR: Mysteries of the Organism, and Sweet Movie raise questions about sexuality and politics which remain important. Keywords Man Is Not a Bird, Love Affair, Innocence Unprotected, WR: Mysteries of the Organism, Sweet Movie DVD DATA Dušan Makavejev: Free Radical [Man Is Not a Bird, Love Affair, or The Case of the Missing Switchboard Operator, Innocence Unprotected]. 1965, 1967, 1968 © 2009 Dušan Makavejev. Publisher: criterion eclipse, 2009. $44.95, 3 discs. WR: Mysteries of the Organism. © 1971 Dušan Makavejev. publisher: criterion collection, 2007. $39.95, 1 disc. Sweet Movie. © 1974 Dušan Makavejev. Publisher: criterion collection, 2007. $29.95, 1 disc. taken from here:

0 Comments

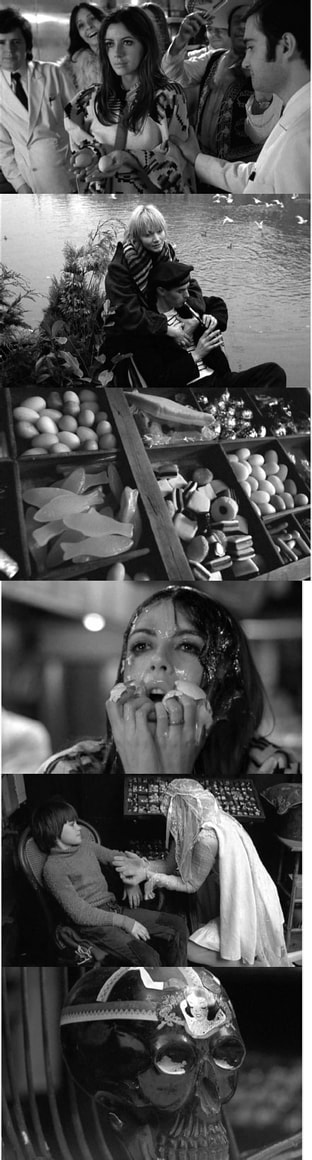

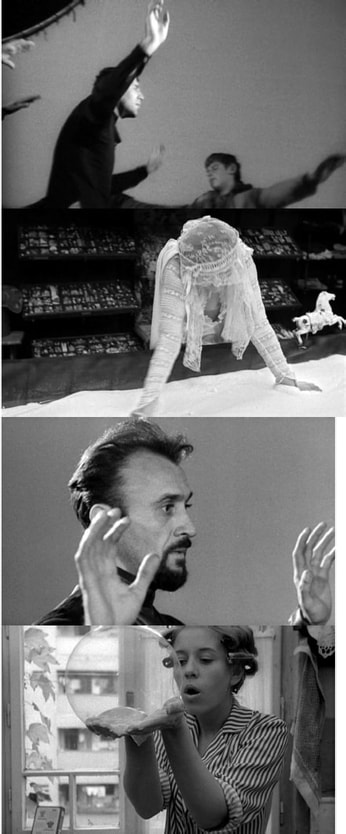

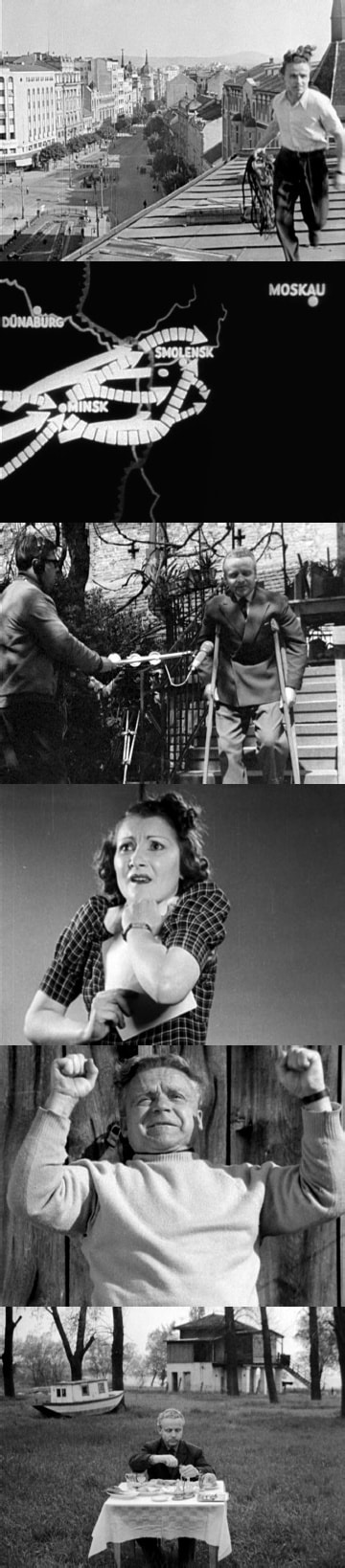

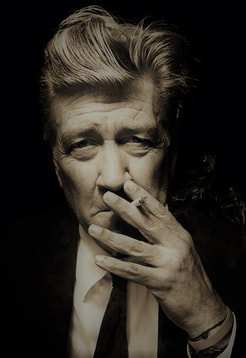

NINA POWER revisits five radical, mixed-genre films from 1965–74 that explore sex and revolution DUŠAN MAKAVEJEV - Mysteries of the Organism Sex is boring: Michel Foucault’s claim in an interview from 1983, from around the time of his History of Sexuality project, is as good a summation as any of our current predicament. What was once seen as a force for radical change—political, physical, social—is now nothing but a tacky consumer addon: “sex appeal” is smeared on everything from shoes to chocolate, from models to cars, and one buys it as one would a cauliflower or some toilet roll. At the same time, despite a general atmosphere of permissive hedonism, the very idea of questioning the sanctity of one’s “private life” is unthinkable: the couple, straight or gay, forms the only acceptable goal of human sexual behavior, even if one sleeps with hundreds of people on the way. The current obsession with “the One,” the perfect lifetime partner—a key motif of supposedly emancipated television shows such as Sex and the City and Ally McBeal—demonstrates that in fact desire is indifferent to whether its object is another human being, a handbag, or a pair of shoes. Sex is boring. But not so very long ago, in an age we are meant to believe was much sillier, fucking was a revolutionary activity and the nuclear family was a nightmare from which the twentieth century was about to wake up. Radical feminism, in particular, in the work of Shulamith Firestone and others, foresaw a world in which technology would free women from the burden of reproduction, liberating true sexuality and permitting as many different kinds of relations, sexual or otherwise, as humanly possible. But despite the accuracy of Firestone’s predictions regarding contraception, IVF, and a certain loosening of everyday morals, no social revolution has occurred. Sexual liberation did not bring with it a corresponding social revolution. We are living, as Alain Badiou often puts it, in the age of the restoration, where creeping moralism and normative models of behavior are sold back to us as objects of desire. Contemporary cinema is, at times, haunted by the memory of these failed aspirations. Some recent films, such as Steven Soderbergh’s The Girlfriend Experience and, in a quite different register, Lars von Trier’s Antichrist, have examined the contemporary state of sex, reduced as it is to an unstable combination of consumerism and morbid inwardness. Both are morality tales for a depressing age: but there is another story to tell, one which represents a course not taken by cinema or the world at large. The films of Dušan Makavejev long for and hint at a society that would not be blind to human pleasure, that would celebrate sexuality without commodifying it. Makavejev’s exploration of visual form, what we might call mixed-genre montage (fiction, documentary, inter views, performance, parody, propaganda), similarly alerts us to the possibility of a new kind of cinema, one that would be able to bridge the gap between big ideas and minor lives. Makavejev is far from mourning lost dreams or reveling in wistful fantasies: what his cinema proposes is not simply “socialism with a human face,” but, as Daniel J. Goulding puts it in his chapter on Makavejev in Five Filmmakers: Tarkovsky, Forman, Polanski, Szabó, Makavejev (Indiana University Press, 1994), “with a human body as well” (236). Maka vejev’s films should also be included in the small but important category of mid-twentieth century feminist films. Indeed, one of Makavejev’s very great strengths is his portrayal of “modern” young women, beginning with Rajka, the strong-willed, independent heroine of Man Is Not a Bird (1965). While it would be easy to read Makavejev’s women as ciphers for all that is left out in the Soviet vision of humanity—playfulness, desire, and a certain carefree autonomy—they are also fleshed-out, engaging characters in their own right. When violence is meted out to the women in Makavejev’s films as it invariably is (the image of a man pushing a woman over features in almost all of the films discussed here, and murderous rage claims the lives of several women), we should not simply understand it as part of the long and dreary history of cinema’s desire to revel in the punishment of women, but as the realization that the long-term goal of changing the world is an awful lot harder than it looks. If it is women who are “going to bring us freedom,” as Makavejev claimed in an interview for Village Voice with Jonas Mekas in 1972, this would have to happen all the way down: the feminist phrase “the personal is political” has never had a filmmaker so willing to try and understand what this might mean as Makavejev. In an age where sex is as dull and omnipresent as any other consumer item, and where western feminism itself is all too often complicit in reinforcing this consumerism, we should ask: what does Makavejev mean to us now? Hypnosis, soap, sugar Man Is Not a Bird (top). Love Affair, or the Case of the Missing Switchboard Operator (bottom left). Sweet Movie (bottom right). © 1965, 1967, 1974 Dušan Makavejev. DVD: Criterion. The five main features under discussion here, Man Is Not a Bird (1965), Love Affair, or the Case of the Missing Switchboard Operator (1967), Innocence Unprotected (1968), WR: Mysteries of the Organism (1971), and Sweet Movie (1974), all recently reissued with new subtitles by Criterion (the first three as a boxed set under the Eclipse imprint), share important similarities, even as they cross from blackand-white to color, from Yugoslavia to America, from simple love story to complex cacophonic delirium. If by 1974’s Sweet Movie, Makavejev had “gone too far” as many thought, and still think, including censors the world over, it should nevertheless be understood as the culmination of a decade’s rumination on sexuality, politics, and the cinematic form. But how do we get from a sweet, if painful, love story set among the harsh lunar landscape of a mining town near Bulgaria (Man Is Not a Bird) to sex murder and the seduction of children on board a boat bearing a papiermâché Karl Marx figurehead drifting down the canals of Amsterdam (Sweet Movie)? To some extent, the more difficult Makavejev found it to be institutionally accepted—by his native Yugoslavia, by international censors—the more he pushed at the boundaries of “acceptable” avant-garde cinema. Just as Wilhelm Reich’s books were burnt in the 1950s and 60s by the FDA in America after first being denounced by the Nazis in the 30s, so Makavejev too was scorched twice over, once by a socialist nomenklatura unamused by his sexualized and irreverent take on supposedly serious political matters and later by a western audience perfectly at ease with his depiction of the pomposity and absurdity of communism but rather less happy with his ambiguous and explicit portrayal of sex, particularly the scenes of child seduction in Sweet Movie. This latter prurience had significant consequences both for the distribution of the film and for the lives of its participants: the British Board of Film Censors denied the film a U.K. cinema certificate in 1975. One of the film’s main actresses, Anna Prucnal, was exiled from Poland, her native country, for seven years on the basis of her role as the revolutionary seductress–murderess. The erotic scenes she performed with several boys offended audiences who would prefer to see children as delicate creatures to be protected from desire rather than sexual beings in their own right. If Makavejev feels a kinship with Wilhelm Reich, however inexactly he depicts Reichian ideas, it is because he too finds himself at odds with the prevailing morality, even as it twists and turns into the twenty-first century. Although some of Makavejev’s ideas and formulations now seem outdated, particularly the gauche depiction of sexual expression, his wilful refusal to provide a secure answer to the problem of how to reconcile the imperfections and contradictions of human desire with the drive toward fault less systems—whether they be socialist, fascist, or capitalist— remains deeply relevant. The materiality of Makavejev’s work, its blunt cuts and disconcerting juxtapositions, as well as its damaged utopianism, remind us that beneath the surface of both the everyday and the universal lies a dark force—like a mischievous child, hopped-up on sugar and desiring destruction. Revealing this barely concealed chaos is, Makavejev slyly posits, only the starting point if one is to harness sexual instincts for organic and nonviolent social ends. If Yugoslavia represented a now-defunct way out of the libidinal dead ends of communism’s striving for perfection and capitalism’s commodification of desire, then Makavejev, as perhaps the republic’s most important director, is the lost prophet of a more hopeful age, never mind that his Yugoslavia was itself a fantasy. In a New York Times interview with Cynthia Grenier from 1971, Makavejev remarked: “The whole world is obsessed with the United States today, the USSR above all . . . Ideally, the perfect society would combine all the pleasures of the American consumer society, which Americans themselves don’t yet know how to enjoy, and the joys and creativity of the October Revolution—pure and truly communal.” Man Is Not a Bird, Makavejev’s first feature, was made in little more than a month on a tiny budget in Yugoslavia in the mid-1960s. Industry rumbles along in the background as a doomed love affair, marital strife, drunken violence, and every day poverty play themselves out in crowded bars, marketplaces, street circus performances, and housing estates. But, as with all of Makavejev’s films, Man Is Not a Bird quickly reveals itself to be far more than this bare description would indicate. Its subtitle, A Love Film, might lead us to believe that the film is chiefly concerned with its two main characters, Jan Rudinski (Janez Vrhovec), a highly skilled mechanic brought into the town (the film is set in the copper-mining basin of Bor) to oversee a project, and Rajka, a tough-minded and humorous hairdresser (played by the astonishingly beautiful Milena Dravic, who will also star in WR: Mysteries of the Organism). While the pair do fall into an odd sort of love— with Rajka renting out a room in her parents’ house to the silent and dour older Jan, and seducing him after a hypnotist’s display before having an affair with a younger man— there is nothing “classical” about this romance. Indeed, its very modernity forces us to rethink what cinema understands a “love story” to be. Man Is Not a Bird opens with a curious indication that this so-called love film shouldn’t be understood straightforwardly. A bizarre figure, Roko, “the youngest hypnotist in the Balkans,” provides some “opening remarks on negative aspects in love,” warning against various kinds of superstitious behaviour. After reeling off a list of such practices—placing bats’ wings on chests to stop people moving, eating frescoes to aid fertility, and so on—he concludes, “you see how we unconsciously use magic in the twentieth century.” The film is a meditation on older and newer forms of hypnosis, on the mass control of people by powerful ideas. But the ambiguous role of hypnosis in the film points to a further problem: what happens when one superstition (or ideology) gets replaced by another? The role of magic, and the fine line between exceptional human activity—strongmen, circus tricks, swallowing snakes, and so on—and sheer manipulation means that all systems are under suspicion. This goes just as much for local cures for warts as it does for entire political regimes. Makavejev’s hypnotists, acrobats, and “men (and women) of steel,” who perform marvels to entertain but not to become role models, are in part a critique of the Stalinist images of Stakhanovite workers, with their perfected bodies and relentless drive. But they are also a more straightforward celebration of the absurdities and wonderments of embodied life. Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari’s materialist question “what can a body do?” is also Makavejev’s: what are the mysteries of the organism? Or, as the intertitles ask in Love Affair, “Will there be a reform of man? Will the new man retain certain old organs?” But the question of bodies is not merely restricted to human beings, for it applies just as much to the many animals and objects captured by Makavejev, whose frames are joyously filled with broken eggs, soap bubbles, sugar, plaster, flour, milk, and chocolate, and, as time goes on, increasingly intimate substances. And Makavejev’s fascination with the limits of materials—how far they flow, how easily they fall apart, how they interact—extends to the material of filmmaking itself. How does a documentary interact with an allegorical fiction? How does propaganda footage relate to a closed domestic scene? Against the backdrop of an intensely cruel and stark landscape, both in its nature and its industry, Man Is Not a Bird looks for moments of laughter and oddness amid the misery. Roko the hypnotist returns to perform his show in the town midway through the other stories of infidelity and burgeoning romance which unite the two main women, Rajka and Burbulovic’s wife (played by Eva Ras, who will go on to play the lead in Love Affair), in a shared enjoyment of watching men kiss one another, hypnotized into believing they are sweethearts. If Makavejev’s women up until Sweet Movie are almost uniformly liberated, modern, and playful, his men are often extraordinarily uptight. They are Party men, decent men, but men repressed and dampened by work and politics nevertheless. The hypnotist’s show induces those on stage to become afraid of nonexistent tigers, then to playact at being cosmonauts (“now we’re all cosmonauts . . . you are bodiless and weightless,” declares Roko) before asking his captive performers to flap their nonexistent wings like birds. The sublime leap between cosmic ambition—between, say, the Soviet space program during the Cold War, and the harsh realities of everyday scarcity such as that experienced by the residents of Bor—is beautifully illustrated by this scene. The hypnotized fail to be both weightless cosmonauts and birds: man is not nor ever could be a bird, however many times he sends himself into space. As Makavejev put it in an interview in this very magazine (winter 1971–72): “I was trying to explain [in Man Is Not a Bird] that you can have global changes but people can still stay the same, unhappy or awkward or privately confused.” In Love Affair, or the Case of the Missing Switchboard Operator, Makavejev tells another unconventional love story, this time between a minority Hungarian switchboard operator, Isabella, and Ahmed, a Muslim Slav who works as a rat catcher. Despite their potentially “outsider” positions, Makavejev doesn’t really play on their status in this sense—they are good workers, good citizens, and very fond of one another for the majority of the film. Yugoslavia, at least in its utopian moments, has risen above petty ethnic and nationalist concerns. Isabella takes in good cheer the one joke Ahmed makes about the supposedly over-sexed nature of Hungarian girls—she is indeed happy to be a sexual being. The shocking darkness of this film comes from the tension-destroying flash forwards in which we see Isabella’s body being raised from a well and carried into a mortuary. Before she even has sex with Ahmed she is dead: the love story is at the same time a tale of murder. The whole setting of the film takes place under the guidance and aegis of two experts, a sexologist and a criminologist, who cut into the story at key moments, including before the main narrative begins. THE EARLY YEARS, 1965–68 In Man Is Not a Bird the sex scenes, as touching as they are, were extracted from their surroundings, shrouded in darkness, as if the couple were somehow removed from the everyday during the act of lovemaking. Here Makavejev takes a more realistic approach, and is all the more successful for it. When Isabella invites Ahmed back to her house (she lives alone after the death of her mother), she makes him coffee, resourcefully using an iron to heat the liquid as her oven is broken, before offering him a stronger drink and smilingly telling him to come through to the bedroom because “there’s a good program on television.” It turns out to be Vertov’s 1931 Enthusiasm, specifically the scenes of churches being toppled by the crowds which are themselves taken from Esther Shub’s The Fall of the Romanovs. Thus we have a fictional couple watching a documentary within a documentary as a form of seduction: the cinematically informed viewer is thus seduced three times over. “It’s more intimate” this way, Isabella suggests, resting her head on Ahmed’s shoulder as they watch Vertov. Makavejev’s signature technique should in principle undermine the narrative comforts of the love story and the linear progression of a series of events, yet his technique of layering “fact” or documentary footage over the top of fiction, what Dina Iordanova calls (in an interview included on the DVD) “associative montage,” serves only to reinforce the ambiguous domesticity of the modern relationship. Even within the frames of domestic life, images of political leaders are dotted around the walls: again, the personal is political—if the great systemic projects of the twentieth century attempted to transform humanity all the way down, then the bedroom is either the final place of minimal resistance or the place most symptomatically colonized: it is Makavejev’s unwillingness to force the issue one way or another that allows him to treat sex as a political allegory but also as an intensely private act. INNOCENCE UNPROTECTED: STRONGMAN LOVE STORY© 1968 Dušan Makavejev. DVD: Criterion Eclipse. Behind all of Makavejev’s playfulness is a relentless and politicized aesthetic project: what is cinema capable of showing? How can it affect us viscerally? Jean-Luc Godard’s claim that “I don’t think you should feel about a film. You should feel about a woman, not a movie. You can’t kiss a movie” is the very antithesis of Makavejev’s manifesto for cinema. Despite certain formal similarities between the two directors, Makavejev’s entire output, from the uniqueness and beauty of the early films to the later explicit film essays on sexuality and politics, we can say that Makavejev is, above all, going to get a reaction out of you, whether you like it or not: Makavejev is the anti-Godard. But perhaps Makavejev’s best film about love is not really a love story at all. Innocence Unprotected (1968), which finishes with a kiss, is, more than any other of his films, Makavejev’s paean to cinema and Serbian cinema in particular. It retraces and remixes the story of the first Serbian talkie, the Innocence Unprotected of the title, which was released under occupation in 1942. Its director and star, Dragoljub Aleksic, is a strongman, a true “man of steel,” banned from performing by the Nazis, who uses a rather clunky romance to showcase his physical abilities. (Similar themes are later resurrected, knowingly or otherwise, by Werner Herzog in his 2001 feature, Invincible, in which a Jewish strongman grapples with the paradoxes of his position under Nazi rule.) Makavejev reunites the remaining cast of Innocence Unprotected, including Aleksi´c, who is still able to bend metal with his teeth and perform various hair-raising stunts, despite the inter vening decades. As Lorraine Mortimer points out in her extremely insightful and comprehensive recent book on the director, Terror and Joy: the Films of Dušan Makavejev (University of Minnesota Press, 2009), Innocence Unprotected represented a novel direction in his work: after the relative success of Man Is Not a Bird and Love Affair, Makavejev could have made a feature that extended his international profile. He would of course go on to do this spectacularly with WR: Mysteries of the Organism and Sweet Movie, but at this point Makavejev explored the touching, local story of one man, Aleksic, of “the artist as industrial laborer,” as Paul Arthur puts it (Cineaste, July 2005). But Aleksic’s story, and the story of the making of the original Innocence Unprotected, is not without its serious political dimensions: not only the dangerous nature of making a film under occupation, however seemingly lightweight its content, but also the subsequent disapproval for having released a film during this period meant that the film itself had been hidden from sight for many years. Makavejev’s “rescuing” of the film in the guise of an atypical making-of restores the humanity as well as the history surrounding the original release, particularly that of Aleksic, perhaps one of the most unusual directors cinema has ever had—neither particularly intellectual nor wealthy, yet able to make this film and get it screened in impossible circumstances. When Makavejev adds flashes of color to the older stock, he stresses the vibrant strangeness of Aleksic’s strongman universe, and the world of a cinema without context. Innocence Unprotected is a trip into the “publicly non-existing” realm of films without peers and without defenders: by focusing on this anomalous event in Yugoslav cinematic history, Makavejev unwittingly presages his own future nonconformity within even the most avant-garde circles. NINA POWER is the author of One Dimensional Woman (Zero Books, 2009), a critique of contemporary feminism. ABSTRACT A reconsideration of the fruitful 1965–75 period in Yugoslav director Dušan Makavejev’s career, arguing that Man Is Not a Bird, Love Affair, or The Case of the Missing Switch board Operator , Innocence Unprotected, WR: Mysteries of the Organism, and Sweet Movie raise questions about sexuality and politics which remain important. Keywords Man Is Not a Bird, Love Affair, Innocence Unprotected, WR: Mysteries of the Organism, Sweet Movie DVA DATA Dušan Makavejev: Free Radical [Man Is Not a Bird, Love Affair, or The Case of the Missing Switchboard Operator, Innocence Unprotected]. 1965, 1967, 1968 © 2009 Dušan Makavejev. publisher: criterion eclipse, 2009. $44.95, 3 discs. WR: Mysteries of the Organism. © 1971 Dušan Makavejev. publisher: criterion collection, 2007. $39.95, 1 disc. Sweet Movie. © 1974 Dušan Makavejev. publisher: criterion collection, 2007. $29.95, 1 disc. taken from:

Mick Eaton and Colin MacCabe

At the time when the social debate is getting angrier and angrier — yet more coherent and specific, he looks very like a man huddling in the shelter of his gadgets mid only through gadgets, and machine-like presentation to admit that human warmth exists.

From a review of Numero Deux Janomy in the Observer, 30 Jan 1977

The lords of imperialism have transformed technology and sexuality into instruments of repression.

From Le Gai Savoir

loading...

excerpt from: Godard: images, sounds, politics

loading...

Laura Mulvey and Colin MacCabe

'Do you know, madame, that despite your very light brown hair, you make me think of a beautiful redhead. La Jolie Rousse is a poem by Apollinaire. "Soleil voici le temps de la raison ardente..." Well, that burning-bright reason which the poet is looking for . . . when it does appear, it takes on the form of a beautiful redhead. That is what can be seen on a woman’s face, the presence of awareness, something which gives her an different, an extra beauty. Feminine beauty becomes something all-powerful, and it’s for that reason, I believe, that all the great ideas in French are in the feminine gender'.

from Une femme est Une femme

Are there objects which are Inevitably a source of suggestiveness as Baudelaire suggested about women?

Barthes

'Following this line of thought, one might reach the conclusion that women have escaped the sphere of production only to be absorbed the more entirely by the sphere of consumption, to be captivated by the immediacy of the commodity world no less than men are transfixed by the immediacy of profit . . .

In the twenty years that Godard has been making movies one of the remarkable features of this work is its closeness to the contemporary moment. Perhaps the most striking example of this is La Chinoise, apparently aberrant when it appeared, yet confirmed in its actuality less than a year Iater by the events of May 1968. But all his films are inextricably locked in with the moment of their making, existing on the sharp edge between observing the world taking and changing share and, in giving it concrete form in representation, being part of the changing shares.

Godard's commitment to a political cinema was signalled in one of his very earliest articles, ‘Towards a Political Cinema’ (Godard on Godard, pp.16-17). Of all the early enigmatic articles it is this one which has proved the most opaque; the English translator commented ‘while most of Godard's early article; are fairly cryptic, this one is almost impenetrably so' (Godard on Godard, p.24). In fact, however, certain clear terms emerge from Godard’s discussion. Talking of a shot from Gerasimov's The Young Guard which he claims sums up the whole o Soviet cinema, he writes:

. . . a young girl in from of her door, in Interminable silence, tries to suppress the tears which finally burst violently forth, a sudden apparition of life. Here the idea of a shot (doubtless not unconnected with the Soviet economic plans) lakes on its real function of a sign, indicating something in whose place it appears.

Godard's insistence that politics in the cinema is a question of signification, the affirmation that the aesthetics the political are intimately linked, an affirmation aided by the linguistic coincidence, lost in translation, that French has the same word for shot and plan, the emphasis on a moment of emotion as the articulation of the political and the personal — all these can be understood as providing some of the crucial terms for Godard’s film-making.

loading...

It is not usual to consider A bout de souffle a political movie; the conventional wisdom is that Godard does not reflect on politics until le Petit Soldat, and yet the terms of the problems of politics are already assembled in the first film. While Michel and Patricia talk and play in Patricia's room, the radio brings them news of the visit that Eisenhower is paying to Paris and to the recently installed Général de Gaulle. The lovers' international affair thus finds a political analogue. And yet the analogy is formal and empty; the distance from the personal to the political is understood as infinite. Later in the film, Michel and Patricia separately descend the Champs Elysees, Michel reading yet another edition of France Soir and Patricia trying to evade the policemen who are following her. Their descent is impeded by crowds of people and the policemen controlling them and as the camera pans across from the pavement to the road we see that the politicians' motorcade is ascending the Champs Elysèes. In fact, we never see the politicians' faces: the motorcade and the police are enough to signal their presence. In the movement of the pan Godard demonstrates the distance between the personal and the political, which is also the distance between the form of the thriller and the form of the documentary. The form of the thriller reduces politics to a momentary lure in the narrative: our only interest in the motorcade is that it explains the presence of so many policemen in terms other than the hunt for Michel. In parallel fashion, any newsreel in which the motorcade figures as a central meaning would see Michel and Patricia only as part of the public gathered to observe the two national leaders.

Throughout Godard early films the search for a form of politics is also the search for a form of cinema which could discuss politics: the thriller again in Alphaville, the war movie in Les Carabiniers. But as Ihc political pressure of the 1900s grew more intense, and particularly the pressures of the war in Vietnam, Godard's search for a form adequate to the demands of politics which would also constitute a politics adequate to the demands of form became increasingly desperate. N o film poses the dilemma more clearly than Masculin/Féminin. The protagonist, played by Jean-Pierre Leaud, occupies the position of the oblique stroke in the title caught between the masculine world of party politics in which his Communist friend, played by Michel Debord, moves so comfortably and the feminine world of teenage magazines and pop music inhabited by his pop singer girlfriend (Chantal Goya). His own desire somehow to unite and transform these two disparate elements of his experience with the aid of fragments of the traditional discourses of Western culture leaves him without listeners in a solitude emphasised when his only audience is provided by a record-your-own-voice booth. The popular forms of art, despite their appeal, are increasingly shown as incredibly ruined by their relation between producer and consumer, epitomised in the cinema audience's indifference to the quality of the projection and the idiotic formula questions that Chantal Goya is asked on behalf of her audience by the interviewer for a pop magazine. At the same time, there is a liberating novelty in the pop music world completely missing from the habitual politics of the French Communist party, frozen in a repressive stereotype which ran not Admit the demands of art or sexuality into the language of politics. For Godard, it is not a question of posing the problem of politics in terms of popular art, nor of posing the problem of popular art in terms of politics. In Masculin/Féminin and the two films lie made concurrently immediately afterwards, Deux ou Trois choses and Made in USA, the problems of politics and art are articulated in the same terms: the terms provided by the forms of cinema.

Godard has never simply accepted the form of the political. So used are we to the daily diet of political information at the international, national or local level that we rarely question the form of politics, the way in which communal decisions are taken and social transformation consciously pursued. It is, of course, the fundamental heritage of the revolutionary tradition that the question of the form of politics is itself political. However, if Leninism was an attempt to hold together this revolutionary truth and the necessity to intervene h» the given form of the political, the party being the new form of organisation which allowed of such a double engagement, the historical subjection of Communist parties to the most narrow definition of the political is a testament to the bankruptcy of the Leninist tradition in the developed world. For us in the advanced capitalist countries there it perhaps no instance so evident of the failure to theorise or practically act on the form of the political as the lack of engagement with the new information media that have developed throughout the century. The effects of this media on the form of the political remains, still, largely unchallenged in theory or in practice. One way in which it is possible to view the whole of Godard’s work is as such a challenge and a challenge that operates at the level of both theory and practice.

loading...

If you want to write a book about me then there is one thing you must put in: money. The cinema is all money but the money figures twice: first yon spend all your time running to get the money to make the film but then in the film the money comes back again, in the image.

Godard in conversation

loading...

Before starling work ou Sauve « jui pent., Godard had spent over six months trying to persuade Robert De Niro and Diane Keaton to star in The Story. Difficulties in the negotiation s finally decided him to .start work first on Sauve qui pout but by then he had already written an extensive script of the projected American film. This script is itself a remarkable document, as Godard illustrates the development of the narrative with a montage of photographs, mainly pulled from previous Keaton and De Niro films. The story’ of the title refers to Godard’s film itself, to the fictional blind child that Keaton and De Niro have in the film, who is, in some sense, the story of their broken relationship, and, finally, to a film Bugsy that a mutual acquaintance of theirs. Frankie is making. It is their work on Frankie’s film thaï brings Keaton, as a researcher. and de Niro, as a cameraman, together again in Las Vegas after years of separation. The film concentrates on the historical links between organised crime and Hollywood but Bugsy will never be made because Frankie dies in a road accident arranged by the Mafia. But we learn a great deal about the projected film and about the character Bugsy Siegel, a legendary Mafia figure who was a friend of Hollywood stars and was engaged in the various film-union rackets before being shot to death. At the beginning of Godard’s film, Frankie comes to the airport to meet Diane and as they drive into town he talks of his film. He says that

'It’d be a good idea to start the story in a documentary style, at the very moment that the evening lights go up like the desire in people’s eyes. People have been working all day long for the industry of the day, in factories and offices. Now they're going to work for the industry' of the night: the money earned during the day will be spent on the night of sex, of gambling and of dreams.'

The text continues with the cryptic phrase. ‘ Let the images flow faster than money does’. It is the relation between money and images and the work and desire implicated in that relation which can provide a starting point for an analysis of Godard’s films.

Frankie, a film-maker, wants his images to hide their financial determinations, to escape their economic basis so they can function effectively as a phantasy. Godard's project is the direct reverse — Co slows down the images until the money appears and (tie phantasy displays its very constitution. And although there can be no question of a simple development — a linear progress towards an ever more comprehensive view — it is undoubtedly the case that the significance of money in Godard's work undergoes a series of transformations. Initially, two images of money are opposed — on the one hand, there is money in is a normal social function where it is understood within a context of work and frustration and, on the other, (here is criminal money which functions within a context of desire and liberation. These initial images which were, and still arc, current in the commercial cinema were transformed by Godard until they produced a critique of the image itself. The relation between desire and money in the image was connected to the relation between desire and money which is the very condition of the image and thus to the position of the spectator. The move from a particular film lo the institution of cinema and the question of the political conditions of existence of that institution are traced particularly clearly in Godard’s work. The condition of this movement is an obsession with the position of woman in the image which leads inevitably to the question of the economic conditions of existence of these images. Nothing more clearly indicates Godard’s later preoccupations than the fact that criminal money in The Story does not appear in relation to a particular character’s desires but in relation to the institution of cinema: the early financing of Hollywood.

In A bout de souffle (Breathless) the narrative development turns around the fact that the money which Michel Poiccard, the character played by Jean-Paul Belmondo, came to Paris to collect and which will allow him to flee to Rome is in the form of a crossed cheque which he cannot cash. This money caught up in a social nexus of financial institutions is opposed to the cash which Belmondo steals from both friends and strangers and which enables him to satisfy his desires without delay, be they to take Patricia (Jean Seberg) out to dinner or to buy himself breakfast. These two types of money set up an opposition between a restrictive social world and one of individual freedom, a series of relations understood within the film as the opposition between normal ‘cowardly' lâche behaviour and abnormal ‘ normal’ behaviour. This opposition is mapped on to sexual difference through the contrast between Patricia's concern with work and a career and Michel’s determination lo live only for the moment. Patricia's final betrayal of Michel is no surprise to the spectator because Michel has already told us that the attraction of her physical appearance cannot disguise the fact that she is a lâche. Woman's attractive appearance hides the reality of her attachment to the social relations which men wish to escape. It is m these terms that one can understand Godard's repeated statement that it is one of his films that he likes least and that he finds it fascist. Its fascism resides in its refusal of the reality of social relations and the propagation of the myth of an existence outside those relations. If A bout de souffle represents the criminal as someone who has abolished any restraint on desire, Godard’s later films reveal this image as too simple, as indeed an image of money which disregards the money in the image.

excerpt from GODARD: IMAGES, SOUNDS, POLITICS by Colin MacCabe

loading...

A man (Gary Cooper) is in a little local train when it is attacked by bandits. Along with two chance travelling companions, a professional gambler (Arthur O'Connell) and a saloon girl (Julie London), he tries to get back civilization. All three land up at the bandit hideout (among the bandits, the tubercular book-lover from Johnny Guitar), and we suddenly discover that the Man of the West is none other than the chief's nephew, who used belong to the gang but gave it all up to lead a more Christian existence under other skies. But the half-crazy old man (Lee J. Cobb) who leads the outlaws believes that his nephew has really come back. Not to disillusion him is according to our hero, the only way of avoiding disaster for his companions. Unfortunately, a cousin turns up unexpectedly. He proves to be much Iess credulous than the uncle. This odyssey finally ends in terrible slaughter in a deserted town. Gary Cooper and Julie London escape unharmed. But not being in love with each other (kissing figures no more prominently in Man 0f the West than in The Tin Star), they decide to go their own ways as the end-title comes up.

The script is by Reginald Rose, who also wrote Twelve Angry Men. So you can see that Man of the West belongs, a priori, to those 'super-Westerns' 0f which Andre Bazin spoke. Although if one thinks of Shane or High Noon, this is likely, still a priori, to be a defect. Especially as, after Men in War and The Tin Star, the art of Anthony Mann seemed to be evolving towards a purely theoretic schematism of mise en scene, directly opposed to that of The Naked Spur, The Far Country, The Last Frontier or even The Man from Laramie. In this respect, seeing God's Little Acre was as depressing as it was catastrophic. Yet this unmistakable deterioration, this apparent dryness in the most Virgilian of film-makers ... if one looks again at The Man from Laramie, The Tin Star and Man of the West in sequence, it may perhaps be that this extreme simplification is an endeavour, and the systematically more and more linear dramatic construction is a search: in which case the endeavour and the search would in themselves be, as Man of the West now reveals, a step forward. So this last film would in a sense be his Elena, and The Man from Laramie his Carrosse d'or, The Tin Star his French-Cancan.

But a step forward in what direction? Towards a Western style which will remind some of Conrad, others of Simenon, but reminds me of nothing whatsoever, for I have seen nothing so completely new since - why not? - Griffith. Just as the director of Birth of a Nation gave one the impression that he was inventing the cinema with every shot, each shot of Man of the West gives one the impression that Anthony Mann is reinventing the Western, exactly as Matisse's portraits reinvent the features of Piero della Francesca. It is, moreover, more than an impression. He does reinvent. I repeat, reinvent; in other words, he both shows and demonstrates, innovates and copies, criticizes and creates. Man of the West, in short, is both course and discourse, or both beautiful landscapes and the explanation of this beauty, both the mystery of firearms and the secret of this mystery, both art and the theory of art ... of the Western, the most cinematographic genre in the cinema, if I may so put it. The result is that Man of the West is quite simply an admirable lesson in cinema - in modern cinema.

For there are perhaps only three kinds of Western, in the sense that Balzac once said there were three kinds of novel: of images, of ideas, and of images and ideas, or Walter Scott, Stendhal, and Balzac himself. As far as the Western is concerned, the first genre is The Searchers; the second, Rancho Notorious; and the third, Man of the West. I do not mean by this that John Ford's film is simply a series of beautiful images. On the contrary. Nor that Fritz Lang's is devoid of plastic or decorative beauty. What I mean is that with Ford it is primarily the images which conjure the ideas, whereas with Lang it is rather the opposite, and with Anthony Mann one moves from idea to image to return - as Eisenstein wanted - to the idea. Let's take some examples. In The Searchers, when John Wayne finds Natalie Wood and suddenly holds her up at arm's length, we pass from stylized gesture to feeling, from John Wayne suddenly petrified to Ulysses being reunited with Telemachus. In Rancho Notorious, on the other hand, when Mel Ferrer makes Marlene Dietrich win on the lottery-wheel, the SUdden feeling of the intrusion of tragedy in a Far West saloon is not so much reinforced as created by Mel Ferrer's foot tipping the wheel - and with it we pass from the abstract and stylized idea to the gesture. With Ford, an image gives the idea of a shot; with Lang, it is the idea of the shot which gives a beautiful image. And with Anthony Mann?

If one analyses the scene in Man of the West where one of the bandits holds his knife to Gary Cooper's throat to force Julie London to strip, one will see that its beauty springs from the fact that it is based at once on a purely theoretical idea and on an extreme realism. With each shot, we pass with fantastic speed from the image of Julie London undressing to the idea of the bandit imagining he will soon see her naked. So Mann need only show the girl in her underwear to give us the impression that we are seeing her naked.

With Anthony Mann, one rediscovers the Western, as one discovers arithmetic in an elementary maths class. Which is to say that Man of the West is the most intelligent of films, and at the same time the most simple. What is it about? About a man who discovers himself in a dramatic situation; and looks about him for a way out. So the mise en scene of Man of the West will consist - here I almost wanted to write, already consists, for Anthony Mann is beginning to express in form what among his predecessors was usually content, and vice versa - of discovering and defining all the same time, whereas in a classical Western the mise en scene consisted of discovering and then defining. Simply compare the famous pan shot which reveals the arrival of the Indians in Stagecoach with the fix-focus shot in The Last Frontier of the Indians just appearing out of the high grass to surround Victor Mature and his companions. The force of Ford's camera movement arises from its plastic and dynamic beauty. Mann's shot is, one might say, of vegetal beauty. Its force springs precisely from the fact that it owes nothing to any planned aesthetic.

Let us take another example, this time from Man of the West. In the deserted town, Gary Cooper comes out of the little bank and looks to see if the bandit he has just shot is really dead, for he can see him stumbling in the distance at the end of the single street which slopes gently away at his feet. An ordinary director would simply have cut from Gary Cooper coming out to the dying bandit. A more subtle director might have added various details to enrich the scene, but would have adhered to the same principle of dramatic composition. The originality of Anthony Mann is that he is able to enrich while simplifying to the extreme. As he comes out, Gary Cooper is framed in medium shot. He crosses almost the entire field of vision to look at the deserted town, and then (rather than have a reverse angle of the town, fol· lowed by a shot of Gary Cooper's face as he watches) a lateral tracking shot re-frames Cooper as he stands motionless, staring at the empty town. The stroke of genius lies in having the track start after Gary Cooper moves, because it is this dislocation in time which allows a spatial simultaneity: in one fell swoop we have both the mystery of the deserted town, and Gary Cooper's sense of unease at the mystery. With Anthony Mann, each shot comprises both analysis and synthesis, or as Luc Moullet noted, both the instinctive and the premeditated.

There are other ways of praising Man of the West. One could talk about the delightful farm nestling amid the greenery which George Eliot would have loved, or about Lee J. Cobb, with whom Mann succeeds where Richard Brooks failed in The Brothers Karamazov. One could also talk about the final gunfight, since this is the first time that the man shooting and the man shot at are both kept constantly in frame at the same time. I spoke earlier of vegetal beauty. In Man of the West, Gary Cooper's amorphous face belongs to the mineral kingdom: thus proving that Anthony Mann is returning to the basic truths.

excerpt from the book Godard On Godard

by David Trotter

Hitchcock liked assembly lines. In the long, consistently revealing interview he gave to François Truffaut in the summer of 1962, he described a scene he had thought of including in North by Northwest (1959), but didn’t. Roger O. Thornhill (Cary Grant) is on his way from New York to Chicago. Why not have him stop off at Detroit, then still in its Motor City heyday?

I wanted to have a long dialogue scene between Cary Grant and one of the factory workers as they walk along the assembly line. They might, for instance, be talking about one of the foremen. Behind them a car is being assembled, piece by piece. Finally, the car they’ve seen being put together from a simple nut and bolt is complete, with gas and oil, and all ready to drive off the line. The two men look at it and say, ‘Isn’t it wonderful!’ Then they open the door to the car and out drops a corpse!

The putative scene has the makings of a classic Hitchcock prank or hoax. ‘Where has the body come from? Not from the car, obviously, since they’ve seen it start at zero! The corpse falls out of nowhere, you see!’ Hitchcock was just short of his 63rd birthday when Truffaut interviewed him. He had remained staggeringly inventive throughout a long, prolific and highly profitable career, and there were seven films yet to come, including The Birds (1963) and Marnie (1964). Two American television series – Alfred Hitchcock Presents (1955-62) and The Alfred Hitchcock Hour (1962-65) – converted the ‘master of suspense’ into an international celebrity. Since his death in 1980, his reputation has continued to soar. He must by now be the most written about film director of all time. In 2012, Vertigo (1958) displaced Citizen Kane at the top of Sight and Sound’s list of the best films ever made. But his art owed a great deal to its affinity with the assembly line.

Even the biographers, watching the life ‘start at zero’, have struggled to establish where the motivation for the inventiveness came from. The most popular hypothesis, not least because Hitchcock himself promoted it so vigorously, concerns timidity. ‘The man who excels at filming fear is himself a very fearful person,’ Truffaut observed, ‘and I suspect that this trait of his personality has a direct bearing on his success.’ The most substantial biography to date, by Patrick McGilligan, includes plenty of anecdotes about fear, but supplies little by way of evidence of its ultimate cause, and draws no conclusions. Peter Ackroyd, however, is firmly of the Truffaut school. His Hitchcock trembles from the outset: ‘Fear fell upon him in early life.’ At the age of four (or 11, or …), his father had him locked up for a few minutes in a police cell, an episode that became, as Michael Wood puts it, the ‘myth of origin’ for his powerful distrust of authority. Ackroyd rummages dutifully for further evidence. Was young Alfred beaten at school by a ‘black-robed Jesuit’? Or caught out in the open when the Zeppelins raided London in 1915? Did he read too much Edgar Allan Poe? It doesn’t really add up to very much. And yet – or therefore – the strong conviction persists. Fear is the key; and not just to the life. Interview the films, he once told an inquisitive journalist. Those who have interviewed the films often conclude that, like their creator, they too tremble. ‘Hitchcock was a frightened man,’ Wood writes, ‘who got his fears to work for him on film.’

For Wood, the question of fearfulness arises most pressingly when it comes to the tortures meted out to the women whose death or danger is a dominant feature of almost all the movies. ‘Is it sadism, as the dark view of Hitchcock proclaims, a pleasure in seeing beautiful women in harm’s way? The solitary joy of the otherwise uxorious director? A revenge on the mother the child thought might leave him for ever?’ Wood doesn’t believe that the motive was sadism. Nor does he think, like Hitchcock’s first biographer, John Russell Taylor, that Hitchcock, far from enjoying the distress he was able to inflict on them, identified strongly with his victims. The women in the movies are, Wood proposes, ‘whatever we most fear to lose’. This ‘we’ may be just a bit too comfortable. There presumably were and still are those, even among Hitchcock’s most ardent fans, who feel that they could get by in life without a regular supply of blondeness. Still, it seems possible to agree that the women in harm’s way represent whatever was most at risk, not just for Hitchcock, but for a culture heavily invested in blonde iconicity. At any rate, I find it difficult to disagree with Wood’s further conclusion. The lingering over the heroine’s demise could, he says, be masochism. ‘But it could also be just an act of thinking the worst, an act of propitiation to the gods who take these treasures away.’ Hitchcock’s films are at their most Hitchcockian, Wood proposes, when they think the very worst. They are certainly lavish in their propitiations: it takes Marion Crane (Janet Leigh) 45 seconds to die in Psycho, but the scene required seventy different camera set-ups. Ceremony enough, surely. But Hitchcock knew that the gods who took the treasures away were not the kind to be propitiated.

The best commentary on this aspect of Hitchcock’s films (and on a great deal else besides) may be Philip Larkin’s ‘Aubade’, a poem about the specific, all-consuming fear aroused by the most general and unavoidable (that is to say, banal) of all conditions. This is the fear not so much of dying, as of death, of mortality. Waking at 4 a.m. to ‘soundless dark’, the speaker sees ‘what’s really always there:/Unresting death, a whole day nearer now’. His mind ‘blanks’, not inwardly, in remorse or despair, but outwardly,

at the total emptiness for ever,

The sure extinction that we travel to And shall be lost in always. Not to be here, Not to be anywhere, And soon; nothing more terrible, nothing more true.

‘And soon’: the mildly querulous bit of time-keeping tucked away among the sonorous negations strikes the authentic Larkin note. For the blankness he has in mind is ‘a special way of being afraid/No trick dispels’: not faith, not courage, not the sound a poem makes.

‘I work all day, and get half-drunk at night’ is how ‘Aubade’ begins. That’s pretty much what Hitchcock did for most of his life, except that as he grew older the drinking encroached increasingly on the work (champagne with lunch, vodka and orange in a flask on set). The justification for the briskness of Ackroyd’s account (259 pages of text, where previous biographers have required twice as much, or more) is that Hitchcock didn’t linger either. He liked to think he could complete one film in the studio while starting another in his mind. The transitions between films became almost as swift and as seamless as the transitions within them. ‘He already had another project in mind’ is Ackroyd’s constant refrain. By the same token, the rare periods of ‘suspended animation’ during the course of a long career, when there were ‘no stories to consider, no treatments to contemplate, no stars to pursue’, became a ‘form of torture’. The final months of his life seem to have been truly harrowing for all concerned. As far as I’m aware, Hitchcock himself only ever approached the topic of our sure extinction obliquely, and in relation to his films. For example, he reassured Truffaut that staging violent death all day hadn’t given him nightmares. He would go home afterwards and laugh about it:

And that’s something that bothers me because, at the same time, I can’t help imagining how it would feel to be in the victim’s place. We come back again to my eternal fear of the police. I’ve always felt a complete identification with the feelings of a person who’s arrested, taken to the police station in a police van and who, through the bars of the moving vehicle, can see people going to the theatre, coming out of a bar, and enjoying the comforts of everyday living; I can even picture the driver joking with his police partner, and I feel terrible about it.

I think the police are a red herring here. All the vividness of the anecdote lies in the detail of the activities visible from the van, now conclusively beyond reach. Hitchcock identifies not so much with the suspected criminal as with the person (any person) whose number is up. The person taken out of circulation – it could be by a police van, or by an ambulance – sees, perhaps for the first time, what the world will be like when she or he is no longer in it. Hitchcock had already incorporated a version of the incident he so vividly pictures here into The Wrong Man (1956), a very good, uncharacteristically neo-realist film about a New York musician under arrest for a crime he didn’t commit. As he’s driven away by the police, the musician (it’s Henry Fonda) glimpses his wife, who doesn’t yet know he’s been arrested, moving around in the kitchen. When describing this scene to Truffaut, Hitchcock dwelled on details that either weren’t in the film to begin with, or got edited out.

At the corner of the block is the bar he usually goes to, with some little girls playing in front of it. As they pass a parked car, he sees that the young woman inside is turning on the radio. Everything in the outside world is taking place normally, as if nothing out of the ordinary had happened, and yet he himself is a prisoner inside the car.

It’s not just that the normality will soon be gone for ever. It’s that it seems to be making precious little effort to stay in touch. The jovial policemen merely perform the indifference society at large is now understood to feel at the removal from circulation of one of its members.

The second film Hitchcock directed on his own was The Pleasure Garden (1925), a British-German co-production made in Munich. At its climax, an alcoholic husband gripped by delirium tremens is shot as he’s about to stab his wife. ‘When he is shot,’ Wood notes, ‘he comes to his senses, no longer drunk at all; he mildly says, “Oh, hello, Doctor,” to the man who has interrupted his fury and dies.’ The version of the film I’ve seen has no intertitle at this point, so I can’t be sure of the exact words. But it’s hard to mistake the jauntiness on the man’s face. The German producer complained that the scene was impossible, and in any case too brutal to be shown. Hitchcock kept it (he may have sacrificed the clarifying intertitle by way of compromise). ‘There is a sense, though, in which a casual, almost negligent registering of one’s last moment is scarier – not brutal or incredible as the German producer thought, but too natural for art, as if the erratic truth of death’s timing were more than we could bear in a story.’ I think that’s dead right. Except of course that nature has little to do with the way people die in Hitchcock’s films.

It took a very special kind of invention to get an awareness of the ‘erratic truth of death’s timing’ into a medium of mass entertainment. In the course of a shrewd and properly demanding analysis of Vertigo, Wood draws attention to sequences of shots in the first hour of the film that mark a narrative threshold: a step-change in its relation to its audience. During these moments, our eyes and ears are ‘co-opted’ for the ‘sense of the world’ somewhat precariously maintained by the agoraphobic private detective Scottie Ferguson (James Stewart), whose old acquaintance Gavin Elster wants him to trail his (apparent) wife, the luminous Madeleine (Kim Novak). We don’t exactly see what Scottie sees, Wood says. Rather, we see what he would see if his eyes were a camera. If Scottie can establish to his own satisfaction that Madeleine is prey to fugue states in which she assumes the appearance and personality of an ancestor, Carlotta Valdes, who committed suicide in 1857, he will feel justified in taking the job, and falling in love with her. In the Legion of Honor museum in San Francisco, Madeleine sits absorbed in a portrait of Carlotta, the bouquet on the bench beside her matching the one Carlotta holds. Scottie watches from across the room. As his gaze narrows, the camera moves in on the bouquet on the bench, and then by a swerve and sudden ascent, on its equivalent in the portrait. Scottie subsequently tails Madeleine home. He peers at her car, across the courtyard from him. Is that a bouquet on the dashboard? It’s as if he believes he could get closer just by wanting to. In the event, the camera does it for him, not by moving in, but by a new set-up, from a different angle, halfway across the courtyard. Yes, it is a bouquet. In Wood’s view, the sheer ‘extravagance’ of these manoeuvres ‘beautifully and scarily exploits the possibilities of the medium’, making our dependence on such possibilities ‘something like an addiction’. We become complicit with everything that has already happened, and everything that will happen, to Scottie.

Such moments had long been a feature of Hitchcock’s film-making, as much of an authorial signature as the famous cameo appearances, if a lot less obtrusive; and a great deal more consequential than the various motifs, riddles, visual puns, and other traces he is sometimes said to have scattered throughout his films. The earliest I can think of occurs in The Lodger (1927), which he himself described as the ‘first true “Hitchcock” film’. Quite distinct from the fluid, intricately choreographed camera movements which have been taken to exemplify his virtuosity (his ‘art’), these five-to-ten-second tracks forward – or, alternatively, the abrupt transition to a new and noticeably discrepant camera set-up within the space originally defined by an establishing shot – are strictly functional. In most cases, the dolly in or the discrepant angle follows a narrowing of the protagonist’s gaze, as it does in Vertigo. In Notorious(1946), for example, Alicia Huberman (Ingrid Bergman), dining in Rio with the Nazi super-scientists among whom she has been planted, notices a commotion around the bottles of wine stood on the sideboard. A dolly in on a label shows us what she would like to see, but can’t quite from where she’s sitting. Now she’s truly hooked; and so are we. In The Birds, after the avian invaders have swept en masse down the chimney of the Brenner house and laid waste to the lounge, Melanie Daniels (Tippi Hedren) watches Lydia Brenner (Jessica Tandy), the mother of the man she’s fallen in love with, picking up broken crockery and straightening a picture on the wall, while her son bickers with the sheriff, who’s come to inspect the damage. After a couple of medium-long shots of Lydia from Melanie’s point of view, a third shot, now from a position she very evidently doesn’t occupy, takes us in much closer. The change of distance and angle is an act of moral and emotional intelligence. While the men bicker, Melanie, noticing Lydia’s distress, has understood something both about her, and about the scale of the catastrophe they all face. It’s the sort of awakening conventional in melodrama. On this occasion, however, awakening has been outsourced to a machine. The changes of distance and angle sometimes arise out of the fiction’s premise. The protagonist of Rear Window (1954), L.B. Jefferies (James Stewart), is a photographer who finds himself confined to a wheelchair by a broken leg, so it makes sense for him to put down the pair of binoculars through which he has been scrutinising the suspicious goings-on in the apartment directly opposite, and pick up a telephoto lens instead. The closer view afforded by the telephoto lens reveals a man wrapping a saw and a butcher’s knife in some newspaper. It doesn’t in fact generate a great deal by way of additional detail; but we think it must do, because we’ve seen Jefferies swap the binoculars for a telephoto lens. Even more interesting are those cases – Blackmail(1929), Suspicion (1941) or The Wrong Man – in which the camera’s swift forward movement or repositioning doesn’t stem directly from the protagonist’s immediate point of view, but nonetheless takes place as it were on her or his behalf. In Shadow of a Doubt (1943), for example, a dolly in on Uncle Charlie (Joseph Cotten) from a position other than that occupied by the person currently talking to him, his niece Charlie (Teresa Wright), confirms starkly to us, but not to her, that he is indeed the killer we already know him to be. In such cases, an alliance has been created between audience and camera, an alliance in suspense: sympathetic to the protagonist, but apart from him or her.

These threshold moments are engrossingly human. They engage us fully in the protagonist’s first full engagement with the world’s meaningfulness. We, too, have been reanimated – thanks to the surrogacy of a machine’s-eye view. The something too natural for art that Wood discerns in the death scene in The Pleasure Garden has found a means other than jesting last words to embed itself in the narrative. Hitchcock, who never forgot what he’d learned as a director of silent films, understood that he didn’t need words at all, jesting or otherwise. For all the light at their disposal, his threshold moments have something of the feel of Larkin’s ‘soundless dark’. They all occur either without a word spoken, or deliberately against (or over) the distractions of speech. Their discrepant soundlessness puts us back inside the police van. The threshold moment could be our last glimpse of the ‘comforts of everyday living’: a world in which a bouquet is a bouquet, a bottle of wine a bottle of wine, a saw a saw, and a woman tidying a tidy woman. We know that the people on the streets are talking to each other as people ordinarily do, but we can’t catch a word of what they say. Psycho confirms the soundless dark of the 4 a.m. hiatus. We expect the threshold to announce itself during the scene in which Marion Crane (Janet Leigh), having just set foot in the Bates motel, fences warily with Norman (Anthony Perkins) in a room full of stuffed animals. But this is a heroine who will be dead before she’s had a chance to notice anything truly suspicious. Hers is a post-mortem awakening. The camera starts on her lifeless face pressed against the bathroom floor, pans to take in the bedroom, and then speeds forward and up until it arrives at the newspaper on the bedside table which conceals the money she had stolen earlier in the day: the grim remnant of her all too human aspiration to a better life.

Of course, there are other kinds of Hitchcock film. He spoke sometimes of the need to adjust the ‘dosage’ of humour from one to the next, and the more humorous among them concern the special fear of dying only in so far as they resemble a trick used to quell it. In the films about nothing very much at all, we learn soon enough to stop worrying about what the villains have in store for the hero and heroine, and start worrying about what the hero and heroine have in store for each other. To demonstrate that romance, like danger, can keep us on tenterhooks, Hitchcock included in Easy Virtue (1928) a scene in which a switchboard operator eavesdrops on a marriage proposal. Pleasurable suspense, and its adroit resolution, took up a lot of space in his bag of cinematic tricks.