|

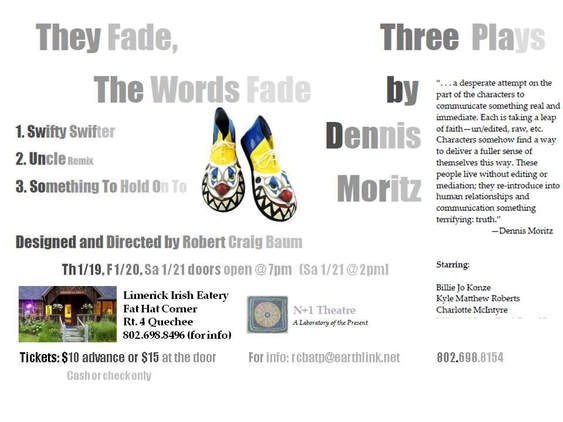

by Robert Craig Baum

Photo: Uncle, Bowery Poetry Club, June 17, 2012 (one of the last avant-garde theatre performances at BPC before it was bought and renovated to become the Bowery Ballroom. Featuring Billie Jo Konze (from Minneapolis, MN) in the lead role.

I

Dennis Moritz—the person, the writer, the auratic voice of theatre’s double—is the subject and object of legend. Anyone who knows anything about Lower East Side (LES) dramaturgy or the Philadelphia avant-garde knows Dennis Moritz. But, strangely, within a few months, his work disappears and you start to wonder if the conversation you just had with that person using this phone or such-and-such email account actually took place. Moritz is neither here nor there. He and his work are wonderfully interdimensional. But, you need to know before reading, before directing, before even thinking of acting in his plays – you need to know that he and his work are a royal pain in the ass to find and develop beyond a one off show or a theatre course or a conversation over bagels in the LES.

Yet at the same time, there’s a performance and paper trail. This theatre does, in fact, exist. Dennis Moritz does, in fact, exist. I have met him. Many times. I have shared meals with him, walked Chelsea with him, watched him eat pancakes in Quechee, VT after our café show They Fade, The Words Fade (January 2012). I have studied his plays as part of my own research bibliography at the European Graduate School (2003-2010) especially when I attempted to revisit ideas from the August Wilson Fellowship (1998-2001) that brought Dennis to me by way of our Mother’s sacred and profane intervention at Penumbra Theatre (April 1999).

But, like the work’s stage and academic classroom history, much like Suzan-Lori Parks’ inclusion then expulsion from The Norton Anthology of American Literature, Dennis’ work has achieved anthological status (Something To Hold On To collection and his poetic entries in Aloud: Voices from the Nuyorican Poets Café (1994).

In a state of utter confusion—which summarizes my three years in Minneapolis-St. Paul as a doctoral candidate before European Graduate School—I received Dennis’ first collection (same title as the play that eluded me before, during, and after my first encounters with Lower East Side artists from the 80s and 90s). It just happened, like the way most of the audience received “Uncle” at the Bowery Poetry Club (June 2012, Father’s Day). Something happened. I was here one moment then I was there and now I’m here again. Before. During. And after (shock) experiences of performing or attending his work.

Once upon a time, the Mother of Us All, Laurie Carlos, stopped me on my way out of a for colored girls rehearsal at Penumbra Theatre in St. Paul, MN April 1999. I was an August Wilson Fellow, she was curator for their new works project. Mother had that look in her eye, the one I associated with “battle stations” aka “I’m about to drop some truth here, Robert, so you better listen.”

Like most theatre students of the mid-to-late 1990s, I was mesmerized by All Things Suzan-Lori Parks; still am. In her work I had found a new way of approaching American theatre from within performance art and other avant-garde traditions, perhaps even the musical (1960s hey day) and classical 19th century (Melville and Hawthorne and Stowe) and modernist 20th century (Faulkner and Ellison and Pynchon). She struck me as a magnetizing force; still does. Very much. Clearly, the producers and creators of Hamilton were also paying close attention to her work both at the time of its ascension into classrooms, journal articles, and granting circles. Perhaps the Hamilton team also located in her work prototypical remixes of American stage traditions (realism, magical realism, hybrid dance/spoken word) as well as encountered a dramaturgy built on the sheer brilliance of Topdog/Underdog, Parks’ Pulitzer Prize winning drama of 2000. It’s hard to say. But, it’s safe to say Hamilton would not have been able to premiere on the Lower East Side at The Public let alone create an Andrew Lloyd Webber/Cameron Mackintosh level audience-loving, history-making, and return-of-investment championing stage spectacle if it hadn’t been for Parks’ work.

Yet, even there, there’s a secret history.

“This is the source, Robert,” Mother of Us All said that April without missing a beat, without releasing me from my look of confusion as I just stared at the cover of Something To Hold On To. She didn’t let up for ten, no seventeen years. I immediately read “Uncle” when challenged to find the “source code.” While sitting in Lowetown, St. Paul at the Red Dog Café, I had my “eureka” moment.

So, I called Mother: “It’s Uncle, isn’t it?” I said with great enthusiasm but with an intonation that also communicated my snickering subversion. “Yes,” She affirmed. I continued: “With the BACA downtown writers and performers there was a before and after ‘Uncle’ moment, wasn’t there?“ / “Yes.” [2]

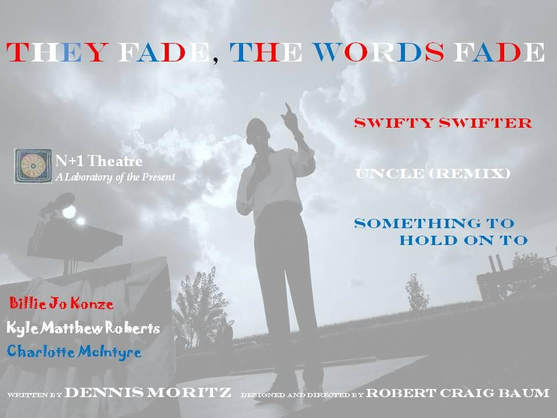

Photo: Poster for THEY FADE, THE WORDS FADE (January 2012, Limerick Irish Eatery, Quechee, VT which is now Pierogi Me!)

(It was like we were speaking in code about the source; two agents working the wings of American theatre’s strange academic and commercial territories. In the theatre lobbies, university libraries, international conferences that brought a strange tribe of dramaturg and dramatist and scholar together in cities far and wide: LA and Minneapolis and Boston and Broadway and DC and Atlanta and Austin and Helsinki and London and Paris and Zurich and Tokyo and Copenhagen and Tallin. Something was up during the late 80s and early 90s that is archived in Dennis’ work, something I immediately recognized. It was like receiving a “Knock, knock Neo” Matrix moment. A tap on the existential shoulder and a hip check out of one cosmological time/space experience into a strange and familiar world. In other words, this experience of reading Dennis Moritz, talking about Dennis Moritz, Facebooking with Dennis Moritz, producing Dennis Moritz (we’ll get to that in a bit!), designing sound and lights and costumes and stage for Dennis Moritz, sharing draft beer and burger and great conversation with Dennis Moritz in White River Junction, VT, shooting the shit in my Quechee, VT living room after he took a nap—you know—like you do—a nap. Talk about a comfortable relationship immediately struck between dramaturg/director/producer and playwright. “Man I’m tired,” he said as he ascended the stairs. My kids and wife introduced themselves to him in December 2011; he and I talked; I could tell he was tired. So, he took a nap in the sunroom. Again, like you do.

While sitting at the dining room table that would become our situation room for They Fade, The Words Fade (four performances at the Limerick Irish Eatery in January 2012) I glanced through the sliding glass door and thought: Is this how it happens? Is this what Mother of Us All wanted in April 1999? Did She know? Had She already visited this moment, you know, Mother style? I think She did. I think She knew. In fact, I know She knew because I asked her October 2015 at Dennis’ apartment during a tempest that shook the CoOps without mercy. “You needed to know that you were and still are—all of you—only working with part of the story. You need this part of the story so we can tell more of the story.”

(See what she did there? She didn’t disrespect Suzan-Lori Parks or prop up Dennis Moritz or challenge the prestige or impact of other Lower East Side playwrights and artists. She merely wanted implant this bit of source code data into the theatre machine and help us all visualize and listen to another conversation within the larger cacophony of expression called the American theatre archive. When she said “all of you,” she was privately challenging us all. Everyone. Theatre historians and dramaturgs and Artistic Directors and the journalists who cover our art and the scholars who publish dissertations and articles and deliver conference papers and conduct regional workshops on contemporary American theatre—this is Mother saying from inside This World observations She has delivered from Between Worlds, what I call in the BlackTheatreWorld project: “the fourth stage of presencing and interdimensional metabolic dramaturgy” (forthcoming).

While holding Something To Hold On To, the Mother of Us All emphasized how “This [book] is what we all were aspiring to achieve back in the day. All of us. Most will deny it. But, Dennis is the source.” She had appealed forcefully to the dramaturg and literary criticism side of my brain. She also activated the writer, the producer, the designer, the composer, the historian, the professor, the fan of theatre that makes me think—transformative and entertaining moments I will never forget. “It’s all inside this book,” she insisted. We then concluded the moment by making some kind of strange impromptu hand-to-hand ritual gesture on the spot (like a kung fu high five or something), and she walked down the road to her car (there was never any parking at the cultural center) as I just stood there holding this book. Very. Confused.

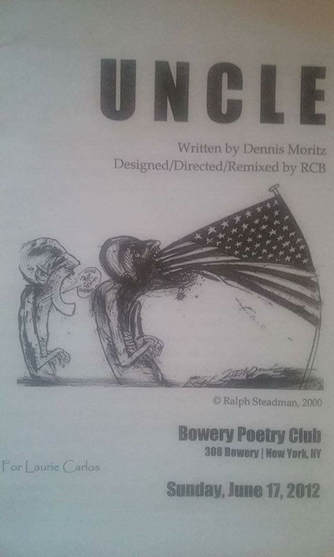

Photo 5: Uncle at Bowery Poetry Club, Program Cover (dedication to Laurie Carlos, image by Ralph Steadman)

loading...

II

I didn't know it at the time, but she was right. This "all" she had described as a source code was a code in and of itself for all theatre of the 1990s and 00s. This "all" was a way of writing I had first encountered in dada, surrealism, German expressionism, Artaud, Genet, Albee, Sarah Kane: an affective, presentational style that had more in common with Brecht and Amiri Baraka than Tennessee Williams and David Mamet. This "all" was big at the time. Suzan-Lori Parks was the rave. Laurie Carlos was the source for Dennis. And now I was handed this book of plays that I instantly loved.

The Mother of Us All reminded me quite a few years later--during another apocalyptic moment of America's cyclical apocalyptic fits, to borrow from Lee Quimby--of the secret this great, underestimated, and wholly individuated theatre movement carried quietly into many different futures: "same room. . . same air" (Laurie Carlos, 2:05am, January 21, 2012).

What she meant by this centers our attention on one of the most radical (though basic) statements about artistic development I have ever encountered: theatre artists work best when supported (and challenged, of course) by a community of theatre artists. It is the job of producers and literary managers and directors and all support staff to nurture this "way" (think Zen) of being-in-the-world. This axiomatic notion drives all that Dennis Moritz has attempted to do since the 80s. This ethical, aesthetic, political, and personal understanding of how to create dramatic art absolutely cannot be fabricated; however, the conditions for this level of intense, productive, supportive, and revolutionary art repeat, recycle, present themselves again in American theatre.

2014 happens to be one of those moments, a quantum leap back and forward to engage, recover, and intensify the process of individual and institutional support that allowed for the emergence of theatre's most intense multiplicities experienced in the 80s and 90s. This is Dennis' time (and space) . . . again. . . .

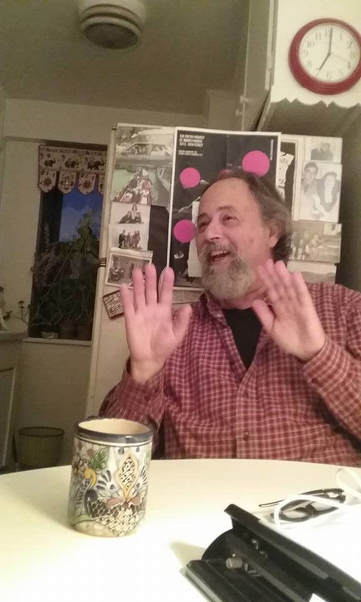

Photo: Dennis Moritz, Grant/Delancy CoOp, same

Laurie and Dennis were forged in the same creative fires of the Lower East Side in the 80s and 90s as Suzan-Lori Parks. His work has been produced all around the country, settling in for a series of encounters at theatre and performance spaces (and projects) like The Painted Bride, the Joe Papp Public Theatre, Nuyorican Poets Cafe, Freedom Theatre, St. Marks Poetry Project, BACA Downtown, and the Bowery Poetry Club. He works regularly with David Marcus and Libby Emmons (Stickies) in New York as one of a series of regular playwrights working in small spaces (like Limerick Irish Eatery and the Main Street Museum in Vermont).

No one writes or thinks like Dennis. When we started regularly communicating with each other on Facebook, theatre wasn't our focus. We were both obsessed with politics and American culture right now in this strange "between" moment so many people thought would be the "promised land" post-Obama. Then, slowly, I realized I was talking with the playwright whose work was thrust in my hands the Mother of Us All.

Like her life's work, Dennis' art helps me breathe a little easier even though directing and performing his work is anything but tranquil. His characters say or half say or stutter their way through and beyond truth in search of something to hold on to. He is utterly fearless, inspiring-- demanding, in a very specific way -- an intellectual, spiritual, emotional, and physical commitment that shatters all artistic and audience expectations.

Plays like Genet at Mettray and Hungry Heart and a revival of Something To Hold On To, Uncle, and Just the Boys by N1Theatre/N1Academy (Vermont and New York City) continues his linguistic, structural, and spatial experiments (as in time space, as in slipstream, as in mesmerism, as in fantasy, as in unraveling the very fabric of what we all might be able to agree on and call "now" or "normal" or "Monday" or "America" or "Planet Earth" which I still think is best described as interdimensionl). Dennis presents these challenges in a way that quite frankly pushes directors and producers and actors and musicians to draw from everything they know, every experience they've had, and every way of thinking they've feared or found comforting -- it is all present. And it is the ultimate theatrical joy ride.

Photo : Uncle at Bowery Poetry Club, Program Cover (dedication to Laurie Carlos, image by Ralph Steadman)

RCB: How's that for the introduction, so far, Dennis? I should try to not be so understated in my enthusiasm about your work.

Moritz: lolololol

So. Why do you think 2017 is the right time to revisit your work, for example, Just the Boys? What features speak to this generation of audience?

Quick cuts. Mosaic structure. Self sufficiency of scenes. Music/choreography construct mini allegories. Brief punchy dialogue. Musical (language) monologues said rhythmically with under music. Coheres heterodox styles. Hail the internet jumbling. Twenty years ahead of its time. Your characters are so vivid and real yet enigmatic. What do you enjoy about them when you read or see them again here in this collection? Boys in the garage, their culture. How they have fun. Their methods of mutual emotional support. The Girls. Their culture. How they enact revenge when dumped. Funny. Jokes. Compelling milieu. Strong individuated characters. Strangeness. Familiarity. Lots of vitality.

Hungry Heart is essentially your meditation and remixing of the life and writing of Anzia Yezierska. Somewhere between adaptation and documentation, your play is unique to both your style and sense that she is still trying to speak to us again, just as you are attempting again. How do you convey this complex story (her life, her work) to the very Lower East Side culture out of which she emerged two or so generations ago?

Mosaic structure. Punchy scenes. Varying textures. A contemporary form. Anzia and Anzia's fiction retains vividness and authenticity as it is transferred into a dramatic idiom. The play is true to the feel and message of the original stories and their moment of composition while using contemporary techniques of structure and presentation. What's the appeal to this generation of Jew and non-Jew alike? The Jewish immigrant culture of the early twentieth century is of inherent interest to the NYC area. Many are descendents of that immigration. Because these stories are heartfelt and of universal appeal and identification, Hungry Hearts can be presented to multiple audiences.

Photo: Our state of the art under the stairs tech space at Limerick in Quechee, VT (January 2012)

What are these themes?

Romantic love. Misunderstandings between parent and child. The inclination of mainstream culture to stereotype and limit access of those judged to be different. So, Anzia and her stories and your project help us to see ourselves differently? Yes. Anzia's life itself is a modern parable. Anzia was born into an orthodox Jewish culture of defined roles. She made a writer's life. In doing this she abandoned traditional role models of motherhood and wife. A modern tale of female emancipation. What kind of access (or limits) does an embrace of multiple approaches to a subject provide you as a playwright? My process opens a way to enter pure art, image and scene jockeying, to enter the theater as art form, which means quick cuts, genre eliding, a way to own a flexibility allowed and expected of museum art, sculpture and painting. I often think my works need to be performed in museums, in museum performance spaces. A release from sequential narration and quotidian assumptions.

I'll jump right to my first, long-standing conclusion: you create multiple worlds and offer audiences a chance to see a single subject from many angles--like a theatrical art installation, a mosaic, a prism . . .

The installation is our mental cosmos. Lovely. Eddying. Eddying out. I write love lyrics and paeans to those sweet moments. Tell me more about how you engage in this process and approach with well-known and lesser-known historical or cultural subjects and themes? The prism fascinates me. Cubism. A deconstruction of cubism. (Joke.) How we appear how we are. Facest. Looks. Faces. Assemblages. I love the schism between how we feel integrated and whole while often existing as an assemblage of fragments. Acts we do intensely. Different. Various. Contradictory. Do they add up. Do they make a continuum. How do we relate to the contrary and dis-related identities we are. Rather than opt for a single through line or rising/falling action and other well-made play elements, you do something else that's fascinated me in particular since first encountering your work through Laurie Carlos and Penumbra Theatre in St. Paul. Tell me more about this "something else." I don’t relate to rising and falling narrations, the action of overcoming obstacles. The football game life, chess and checkers. Not how I experience life. Intermitances. Moments. Extended metaphors, radiant and informing. A plane or plate pulled out from a cubist simultaneity. One or two planes at a time. That is true to memory and reference. Discrete memorable events that continue to inform.

Here's where I find your life as a playwright and life as Dennis Moritz inseparable. One of the most "memorable events" you often site in our conversations over the years is your experience with BACCA downtown.

Yes. What was it about that experience that stayed with you? At BACCA the audience was assumed. We did not write for the audience. We wrote to extend the dramatic form and give voice to our idiosyncratic (idiomatic) selves. Subjective was sacred, where it all started. I continuously broke form. Even from work to work. I took that to be my job. A fabulous audience sold out BACCA. They went with us. Working hard with us. An obsession for the new and the authentic.

What lessons from BACCA can be carried forward to this moment? Perhaps some kind of embedded program or workshop. Digital archives (like a BACCA wiki) are already in the works at the N1Academy. But, BACCA strikes me as different from "community outreach" or "education" platforms. How does the BACCA experience get archived and yet not just become another theatre movement or moment stored on dusty shelves of theatre history's very limited, and extremely slanted memory.

Much work at BACCA originated from the nitty gritty struggle to stay alive and sane. Radical formal experiments devised to give those struggles shape and power. The BACCA theater scene educated. It should be parsed, imitated, reconstructed, reconstructed differently. Intense learning happened there. We were drawn together. My plays directed by artists. Distinct visions. Productions heavy with their subjective DNA. Fascinating to me as a wordsmith, a writer of theater pieces, theater works. After the first experiences I stopped including notes. The auteurs were going to rip. I took my challenge to write words that of tough identity and clear process. The auteur visions at BACCA almost always stayed true to the essence of my work. So, we need to build an archive of this disappearing work, right? Let the folks who were at BACCA have their say. Interviews. Preserve archival videos, pics, programs, artistic statements, reviews. Remount the many seminal productions. Archive the scripts. Archive artist careers.

Here's where drama and history and life and archive seem to come together in your work. In many ways, human beings--you know, the people who come to theatre--live lives that are extremely prismatic. How does that relate to the personalities and figures and (dare I say) "auratic individuals" who populate your drama?

Historical figures are prismatic, talked about, argued about, enmeshed in events that elicit debate. Their lives over we know them through report. There is a tendency to bowtie and clean up the narrative. I’m not interested in that. Life is fragmented, scattered, clear moments and fog. Instead of sequential narrative, I write scenes that are tiles, moments as part of a mosaic. Audience does assembly. The overview, metaview, even elements of narration, is the audience property. The theatre piece is a point for audience departure and interpretation. Like any other work of art. You tell me what it means.

Photo: Robert Craig Baum taking a page out of Tadeusz Kantor's directing playbook when he insisted he and the cast bring personal items to demarcate the stage area (as well as found objects for costumes and makeup and sound design)

III

It is my hopes that Genet at Mettray: Collected Plays of Dennis Moritz will serve as a source code for the reader, the scholar, the producer, the director, the colleague, the undergraduate and graduate student of theatre in general, Lower East Side and Philly theatre of the 80s and 90s through today.

May it fuck you up forever. May it challenge your comfort zones about theatre history, dramaturgy, theatre theory, historiography, theatre archivization, the academic territorialization of one set of theatrical memories over another. May it stay with you and shift how you think about other kinds of theatre, popular or not, international or national, poetic or realistic or surrealistic or Noh. May Dennis’ life’s work, found in both the Something To Hold On To and Genet at Mettray, disrupt, disturb, and deconstruct your notions of how to build a character, how to stage a scene, how to create events within scenes that become larger events the way a cluster of ideas and images ebb and flow, appear and disappear in cinema and other digital arts. May this work empower your craziest and zaniest and least orthodox understanding of who you are and what you do as a person or a playwright, director or dramaturg or theatre historian. May he surprise you. May he encourage you to search for and embrace all surprises that happen inside the theatre world of living ideas, moving concepts, and playful poetry.

May his work also serve as a burr, an errant burr that constantly asks for your attention, all of your attention. Not just a bit of this theory or a bite of that dramaturgical tradition. But, all of you. May it invite you to bring all of you to the space, mental and theatrical. May it forever prick your mind and cause you to remember who you are and what you want to do inside and outside the theatrical mentality of people and situations that simply are – they are here – they are a part of who we are – these characters, these situations, these events, these poetic shadows are all parts of a greater whole that Dennis sees as a structure, a method, a way to move through all the world’s stages.

So, we should remember him. Even if just for this moment. More than an exercise in dramatic memory and collective response to the human condition, Dennis’ theatre is a metabolic dramaturgy that demands all of you. . . yes, all of you. Yes. He has written short plays and poetic fragments and multiple act performances. His monologue Uncle inspired and influenced the early work of Suzan-Lori Parks as an extension of Dennis’ now three decade long friendship and collaborations with the Mother of Us All.

Yes. People in “the know” have considered Dennis’ work some of the strongest dramatic prose and performance art and experimental representational practices written this side of the Reagan Vampire.

Yes. His work remains under-produced—almost forgotten. But, it is this mystical quality and aporetic tendency of his work to become nomadic and foreign and strange yet at the same time as familiar as breathing. Yes. Dennis’ theatre an uncanny spectre, something familiar and strange like an invocation for his actors, collaborators, and audiences to finally deal with unfinished business (the literal definition of spectre).

Yes. Each time his work is performed, the artists must create new rituals and new ways of moving and talking and develop new approaches to poor theatre. Sometimes, it’s imperative to say “fuck it” and go out to the Dollar store and find some party favors for Something To Hold On To or Salvation Army store clothing racks for Uncle costumes.

Yes. Even sound design for a Dennis Moritz show becomes an overwhelming dance with Everything and an unbearable collation and elimination and application process where sound contributes to a spectacle space without any of the budget, any of the support staff, or any of the latest equipment.

Yes. You can design and direct a Dennis Moritz show from under the stairs of an Irish eatery in Quechee, Vermont with as much audacity as expected at the old Bowery Poetry Club or Nuyorican Poets Café or Temple Univerity or Freedom Theatre or Theatre Ariel (Salon)

Yes. This is the theatre of Yes inspired by the theatre of Noh. This is theatre that affirms the fragility and resiliency of the human condition. This is poetry in motion, poetic presentations of people, places, things, ideas, histories both hidden and obvious. Yes. This is theatre. This is the kind of theatre I want to write and direct and perform until my last breath. This is my friend, my mentor, my partner, my reason for even bothering to do theatre again after the death of August Wilson in 2005. This is why I live to read his words in public, perform them for students, explore them in my writing, encourage others to do the same. This is an affirmation of life. A celebration, if you will. But, it is also a work of mourning that inspires others to remember themselves and their families and their whole forgotten (or burned to death) histories.

This is how the legend ends for me. In another moment of anticipation. A hoped for encounter with myself or someone like myself who desperately right now needs these words, needs these plays, needs to understand how theatre functions at its deepest source code so this person, this new me, can also stand in the presence of the Mother of Us All with a look of confusion and excitement, exhaustion and wonder as you or I or Dennis or anyone holding this book pass it on and on and . . .

Notes:

[1] The play Something To Hold On To is a demented rom-com telling the story of a has-been clown, his lovers, and a best friend/stalker/mad hatter/interloper/pain in the ass named Ranton. I played Ranton in the Quechee, VT performances. I would play Ranton forever if I had the energy or inclination. A force ten powerful monologue placed inside an already deconstructing series of relationships that slip with harrowing emotional and psychological power.

[2] Uncle is a monologue ostensibly told by a homeless man or woman of an unidentified ethnicity which captures Moritz’s fascination with the moment, telling the story of the moment, even if the moment unravels out of the control of both the playwright and the character speaking the playwright’s words.

Portions of “Source Code” will appear as the Introduction to Genet at Mettray: Collected Plays of Dennis Moritz. © 2017 Dennis Moritz © 2016, 2017 Robert Craig Baum

Robert Craig Baum is the author of Itself (Atropos 2011) and Thoughtrave: An Interdimensional Conversation with Lady Gaga (punctum, 2016). He is a philosopher, writer, producer, and philanthropist from Long Island, New York. He lives in Washington DC with his wife and four boys where he just completed his first industry screenplay and remains fast at work on THYSELF (follow-up to 2017 book).

https://buffalo8.com/

loading...

2 Comments

|

Archives

February 2020

Theater as particular art. Theater makers, theater plays. etc ... |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed