|

by Steven Craig Hickman

Dark Digital Art by David Ho

…we are in a sort of bubble of irreality: spurious world generated by— the plenary powers, astral determinism, whatever the fuck that is.

—Philip K. Dick, The Exegesis

John Dewey once said that the “serious threat to our democracy is not the existence of foreign totalitarian states. It is the existence within our own personal attitudes and within our own institutions of conditions which have given a victory to external authority, discipline, uniformity and dependence upon The Leader… The battlefield is also accordingly here– within ourselves and our institutions.”1 Of late I’ve begun to see Erich Fromm’s point that what men fear is what drives them to escape into tyranny rather than freedom, and it is autonomy and freedom above all that humans fear most.

Couched as his work was in Freud and Existentialism Fromm would seek an understanding of why humans feared freedom or, as he’d suggest – aloneness, isolation, independence. In his simplistic diagnosis he’d discovered over time that people choose two paths of escape from aloneness. The first path was a positive acceptance of autonomy and separateness, and these individuals would confront themselves and the world in such a way they can relate themselves spontaneously to the it in love and work, in the genuine expression of emotional, sensuous, and intellectual capacities; each can thus become one again with man, nature, and themselves, without giving up the independence and integrity of their singularity. (Fromm, 120) The other form would take a darker turn, one that would force such individuals who suddenly awakened intto aloneness, freedom, and autonomy to feel anxiety, panic, and ultimately run scared, leading them to seek complete surrender of their unique and singular lives, and the integrity of the self, to an external authority in total self-abnegation of their former freedom and autonomy. (Fromm, 121) As he’d remark of this second path of escape, such persons “show a tendency to belittle themselves, to make themselves weak, and not to master things.

Quite regularly these people show a marked dependence on powers outside themselves, on other people, or institutions, or nature” (121). They seek security, safety, and protection even to the point of becoming ensnared and enslaved to authoritarian rule and regulation in every detail of their lives. Passively accepting even the most atrocious forms of discipline and control over their minds and bodies. (Think of such tyrannies as North Korea?) In fact, Fromm like Karen Horney would come to the conclusion after years of case studies of his patients that both the masochistic and sadistic strivings within individuals tend to help them to escape their unbearable feeling of aloneness and powerlessness, accepting the most heinous existence under unbearable conditions if they no longer have to think or be at risk in the world. (129)

Being Alone Together

I believe that in our culture of simulation, the notion of authenticity is for us what sex was for the Victorians—threat and obsession, taboo and fascination.

—Sherry Turkle, Alone Together: Why We Expect More from Technology and Less from Each Other

In one of his interviews J.G. Ballard would remark that there would come a time in the near future when it would truly be possible to explore extensively and in depth the psychopathology of one’s own life without any fear of moral condemnation. “Although we’ve seen a collapse of many taboos within the last decade or so, there are still aspects of existence which are not counted as being legitimate to explore or experience mainly because of their deleterious or irritating effects on other people. Now I’m not talking about criminally psychopathic acts, but what I would consider as the more traditional psychopathic deviancies. Many, perhaps most, of these need to be expressed in concrete forms, and their expression at present gets people into trouble. One can think of a million examples, but if your deviant impulses push you in the direction of molesting old ladies, or cutting girl’s pigtails off in bus queues, then, quite rightly, you find yourself in the local magistrates’ court if you succumb to them. And the reason for this is that you’re intruding on other people’s life space. But with the new multimedia potential of your own computerised TV studio, where limitless simulations can be played out in totally convincing style, one will be able to explore, in a wholly benign and harmless way, every type of impulse – impulses so deviant that they might have seemed, say to our parents, to be completely corrupt and degenerate.”2

In J.G. Ballard’s last trilogy of novels, Cocaine Nights, Millennia People, and Super Cannes he explores this sense of the psychopathology of aloneness and how it touches base with technology, sex, and death. In each of these novels we see this sense of simulation become activated, as if Ballard were already enacting in the pages of these works the cartography of a new psychopathology arising out of our bankrupt culture of young executives whose lives must be activated by voyeur parties based on extreme forms of sex and violence. Extreme decadence has always been aligned itself with perversions of technology and nihil, the psychopathology and the sensual inroads of death and desire have always found themselves close to the moneyed classes whose extravagantly luxurious lives are privy to boredom and suicide. But in our time the true magus of psychopathy is the chameleon and mime artist of emotion, lacking all emotion he can call it out of others like a puppet master in a carnival of dark mirrors. Peoples lives are so drained that to exist in the 24/7 world of automation the new knowledge worker must expose herself to the rape of psychopathic troubadours who become guides into the closing circles of capitalist desire.

Remy de Gourmont once likened decadence in its original meaning as the “idea of natural death,” but that in 1885 under the auspices of Stephen Mallarmé and of the literary group in his circle, the idea of decadence has been assimilated to its exact opposite— the idea of innovation.”3 He’d speak of the modernist as decadent, as one who produces “a poetry full of doubts, of shifting shades, and of ambiguous perfumes”. In a humorous aside he would speak of decadence as style or fashion, or as he delighted in saying, “an intellectual epidemic”:

It was said long ago, considerably before M. Tarde had developed his theory of social philosophy, that “imitation rules the world of men, as abstraction that of things.” This law is very evident in the particular domain of art and of literature. The literary history of decadence is, in sum, nothing but the chart of a succession of intellectual epidemics.

The influence of decadence on many of Ballard’s own stories and novels is apparent to the aficionado. As one interviewer suggested:

KRICHBAUM/ZONDERGELD: Up to now we still haven’t mentioned your Vermilion Sands stories. It seems as if there the influence of decadent literature makes itself felt, of the fin de siècle.

BALLARD: You’re thinking of Huysmans here? Yes. You know, Vermilion Sands corresponds to my vision of the future. It will not be like Nineteen Eighty-Four, but rather like Vermilion Sands. If one goes to the Mediterranean coast in the summer, one sees the future there already. Half of Europe finds itself in this linear city that runs from Gibraltar to Athens. A city that’s three thousand miles long and a hundred metres wide. And that is, in my opinion, the future. (Extreme Metaphors, KL 1912)

This is a dense world, a world in which the city as megacity has forever naturalized the artificial and decadent, where nature has disappeared into the artificial worlds of our Human Security Regimes (Land). In another interview the interlocutor would liken decadence to a “guilty pleasure”. Ballard would respond, saying, “The guilty pleasure notion isn’t to be discounted either, the idea of pursuing an obsession, like the black theme in Joris-Karl Huysmans’ A Rebours, to a point where it is held together and justified only by aesthetic or notional considerations, beyond any moral restraints. A large part of life takes place in that zone, anyway.” (EM, KL 3236) This sense of life beyond good and evil, lived in a realm of aesthetic innovation where reality takes on the fascination and glamour of a simulated universe of play. It’s this movement into the cyberdrift of our network society, where anonymity spawns the unbidden power of sadomasochistic desire unchecked by the normal restraints of social relations and instead allows the anonymous multitude to explore those guilty pleasures which in our time have awakened certain psychopathological disorders and perversions in the machinic realms of our technoutopian apparatuses. The city itself has become a desiring machine, one that offers in its hologrids and Google glassed adverts a continuous flux of sex and violence, ghosts in the shell of time floating through life not at living artifacts but rather as robotic toys in a dreamland of corrupt desire.

As an optimist and libertarian Ballard’s notion of freedom is both exploratory and experimental, speaking of Baudrillard’s notion of America as a simulation of itself he’d remark,

I think America, as a Baudrillardian image of itself, is far more seaworthy than the notional original that most Americans believe in. But I think the old Conradian notion of immersing ourselves in the most destructive element is still true. That’s why I’m a strong libertarian – within the constraints of the law – and believe in exploring all the possibilities open to us. I think the logic of the late twentieth century, and certainly the twenty-first, if I’m around to see any of it, is so governed by our information and communication systems that an ever-greater freedom is inevitable. As people have said, once they invented the Xerox machine, totalitarianism – certainly, Russian totalitarianism – was doomed. (EM, KL 5114)

This sense that replication, mimesis, simulation were antagonistic to systems of closure, to totalitarianism – which in his sense was a false totality with no outside or inside, but rather a doomed venture in a maze of terror and pure freedom, where technological innovation and reality modeling afford each and every person their own private hell.

In his last three novels he would simulate an extreme scenario in which he’d toy with the psychopath as mediator of the brave new world we’d be facing in the parametric spaces of the computational 21st Century. Each of the novels would be based on an investigation of this new world of psychopathology, allowing Ballard to uncover the dark desires at the core of our technocommercial society of High Finance and technological sophistication. This notion of our accelerated world of simulation was a new form of mimetic self-sacrifice, of a birthing process in which humanity was rewriting, rewiring, and reprogramming the very notions of culture and society, and that as he said of Baudrillard’s America and his own Hello, America!: “America is an imitation of itself – its imitation of itself is its reality – which I think is true. But he takes an optimistic view of America, and I would do the same about the world as a whole.” (EM, KL 5110) It’s this notion that reality has become simulation, that the artificial has replaced the natural; or, that artificial has been naturalized (i.e., denatured). This sense of reversal, of living a world turned inside-out, as if Plato’s Cave had given way to a deeper world of shadows in which the copy of a copy had become more real that even our projections on the screen. That we’ve entered the screen or terminal zones of our computational existence, allowed ourselves to fall forward into the simulated universe, become mathematical or abstract entities, sigils or programs to be called forth from our zombiefied existences by Psychopathic Thereapeutics.

In his recent book Heroes: Mass Murder and Suicide Franco “Bifo” Berardi reminds us that in the last few decades, “artistic sensibility has been paralysed by a sense of paranoiac enchantment: psychic frailty, fear of precariousness and the premonition of a catastrophe that is impossible to avoid. This is why art has become so concerned with suicide and crime. This is why, very often, crime and suicide (most of all suicidal crime) have been modelled as art.”4 It’s this sense that our lives have taken on the simulated quality, that we play at the notion of committing terror, atrocities because they are no longer real to us in the old way. That they are mere simulations and we are but programmed entities in a simulated world, an unreal world. A need to create an aesthetic of the unreal, of death. To become the living embodiment of entropy and decay, to resolve the world into that pure moment of zero intensity. Absolved of guilt, the pleasure of calling down the moon of violence in an orgiastic deluge, an apocalypse of spasms.

As Berardi would ask, the question now is to see what’s left of the human subjectivity and sensibility and of our ability to imagine, to create and to invent. Are humans still able to emerge from this black hole; to invest their energy in a new form of solidarity and mutual help? The sensibility of a generation of children who have learned more words from machines than from their parents appears to be unable to develop solidarity, empathy and autonomy. History has been replaced by the endless flowing recombination of fragmentary images. Random recombination of frantic precarious activity has taken the place of political awareness and strategy. I really don’t know if there is hope beyond the black hole; if there lies a future beyond the immediate future. Where there is danger, however, salvation also grows – said Hölderlin, the poet most loved by Heidegger, the philosopher who foresaw the future destruction of the future. Now, the task at hand is to map the wasteland where social imagination has been frozen and submitted to the recombinant corporate imaginary. Only from this cartography can we move forward to discover a new form of activity which, by replacing Art, politics and therapy with a process of re-activation of sensibility, might help humankind to recognize itself again. (Heroes, KL 106)

This sense that we’ve become copies of ourselves, mere simulations, ghosts. Speaking of the ghosts in his life, the late Mark Fisher talking of Rufige Kru’s ‘Ghosts Of My Life’ remarks,

I’ll always prefer the name Jungle to the more pallid and misleading term drum and bass, because much of the allure of the genre came from the fact that no drums or bass guitar were played. Instead of simulating the already-existing qualities of ‘real’ instruments, digital technology was exploited to produce sounds that had no pre-existing correlates. The function of timestretching – which allowed the time signature of a sound to be changed, without its pitch being altered – transformed sampled breakbeats into rhythms that no human could play. Producers would also use the strange metallic excrescence that was produced when samples were slowed down and the software had to fill in the gaps. The result was an abstract rush that made chemicals all but redundant: accelerating our metabolisms, heightening our expectations, reconstructing our nervous systems.5

It’s this feeling even in our music that we are in the midst of a mutant transition, that we are being rewired by the futurial forces of some far flung intelligence that is luring us forward into a brave new world in which we as humans are accelerating ourselves out of flesh and blood and into the very technical modes of existence of which our simulated worlds are made. The impact of this is producing in some a breakdown rather than breakthrough, causing havoc and chaos at the edges of sanity. Fromm in The Sane Society suggested that the Liberals, since the eighteenth century, have stressed the malleability of human nature and the decisive influence of environmental factors. True and important as such emphasis is, it has led many social scientists to an assumption that man’s mental constitution is a blank piece of paper, on which society and culture write their text, and which has no intrinsic quality of its own.6

In our own time we speak of plasticity or the sense of mutating identity, of becoming other than we are, migrating from mask to mask, personae to personae. As Catherine Malabou in her The Ontology of an Accident remarks “We must all of us recognize that we might, one day, become someone else, an absolute other, someone who will never be reconciled with themselves again, someone who will be this form of us without redemption or atonement, without last wishes, this damned form, outside of time. These modes of being without genealogy have nothing to do with the wholly other found in the mystical ethics of the twentieth century. The Wholly Other I’m talking about remains always and forever a stranger to the Other.”7

It’s this sense of becoming not only someone else, but of becoming something else that has entered our contemporary moment of the posthuman or non-human. The notion of a mode of existence in becoming technology, of merging with the machinic systems of which we’ve been so enamored. A feeling that humankind is breaking down the dyad of self/screen which will eventually dissolve the distance between human/machine so that our flesh will become machinic in an absolute mechanosphere outside the genetic markers and trace worlds of flesh and blood. A Transcendence-in-immanence, a movement from kind to kind. We speak of the technological singularity as a sort of event horizon beyond which nothing human gets out alive (Land). A moment when the future implodes on the present and we suddenly transcend within the immanent fields of force that are organic and anorganic, vibrant and inert matter reverse poles and enter the double gyre of a time-machine absorbing us into machinic becoming. Fantasy? Reality? In a simulated world such as ours do such notions even matter? In such a world the human body will vanish, and the traces of its disappearance will only be indexed and registered in the digital avatars and dividual data sets of virtual world become actuality, where life is calculable in 0’s and 1’s. In that time of no time humanity will have forgotten itself and become totally other…

1 Comment

by Steven Craig Hickman

We are so deeply mired in our philosophies as to have evolved nothing better than a sordid version of the void: nothingness. – Emile Cioran

Bataille seems to me far less an intellectual predicament than a sexual and religious one… – Nick Land

loading...

CONTEMPORARY COSMOLOGY

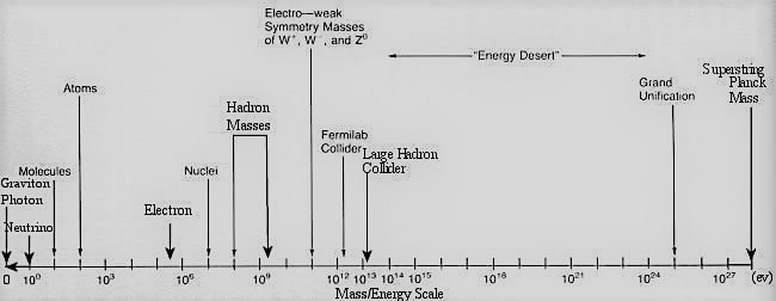

As we approach Halloween I began thinking of current philosophical and poetic thought on the hidden world of things. Reading an article on NASA recently the authors reminded me how little we know about the universe. What little we know describes a universe in which most of the matter and energy that makes it up is invisible to both technology and the human equation, invisible to our senses, a ruin in the fabric of time. The stuff that we see around us in the universe: the stars, galaxies, suns, planets, etc. are made of baryonic matter which accounts for only 4.6 percent of the known universe. While 24 percent is made up of something scientists have ironically termed ‘cold dark matter’, leaving the rest of the universe in a seething ocean of what they like to call ‘dark energy’ which makes up a whopping 71.4 percent of the universe. As one article describes this dark stuff that is hidden from us, unrevealed and so far undetected but rather predicted by mathematical theorems:

It’s known as dark matter, which is itself a placeholder – like the x or y used in algebra class – for something unknown and heretofore unseen. One day, it will enjoy a new name, but today we’re stuck with the temporary label and its connotations of shadowy uncertainty.

Yet, underscoring the structure of this anomalous dark matter is the unqualified power of dark energy, a force that seems to run through all things, ourselves included – undetected and unbidden. We quietly run our eyes across the baryon spectrum of light and matter visible to our senses as if it were the greater part, when in fact it is but the miniscule and vagrant corruption of a ruinous thought – a kenoma or cosmic degradation.

Nick Land in his reading of Bataille will remind us all “energy must ultimately be spent pointlessly and unreservedly, the only questions being where, when, and in whose name this useless discharge will occur. Even more crucially, this discharge or terminal consumption… is the problem of economics.” (Land, 56) Might it also be the problem of cosmology? As we think of that seething sea of dark energy moving through us, its influx of unimaginable power flowing through our bodies and the universe one wonders just how close to the truth Bataille was as he dreamed of ‘expenditure’. Could it be that what we perceive around us, this baryonic matter is none other than the waste product of this vast ocean of dark matter and energy? And, might not the great engines of consumption, the stars, galaxies, and black holes at the center of these churning systems of heat-death be none other than the slow sepulchral consummation of even darker systems than we have as yet begun to imagine in our theoretic dreams of reason? or understanding? What if all we see around us in this visible universe of dust and light is nothing but the byproduct of endless expenditure, an excess expunged by the engorgements of a darker world of forces that the ancient dreamers, shamans, and Gnostics could only hint at in their negative theologies, and our scientists can only mathematize in their theoretical alchemy of this universal degradation and catastrophic trauma? What if we are mere shit in the drift of things unseen? Dead waste in a floating sea of black impenetrability? The Big Bang nothing more than a burp in the body of some great blind entity roiling in its own excess? Is this madness, a metaphoric marshalling of strange tales from heresies of dead worlds?

Modern cosmology stripped of its ancient lineage of myth forces the cosmos into the procrustean bed of a bare and minimal system of holographs, strings, and vibrating systems of chaos and order. Has this given us anything better than the older myths? Is this universe bled of its fabrications, emptied of our desires, become a mere artifact of our insanity – an indifferent and essentially blind machine without purpose or telic motion? And, even if we revitalized a gnosis stripped of its redemptive qualities, its soteriological thrust how will we move those dark forces to reveal themselves? How unconceal their potential by way of math and technology? And, to what ends? Utilitarian ends for some human destitution? A bid to enslave the elements, develop even greater destructive power than our atomic weaponry? Are we nothing more than sorcerers nibbling at the table of existence, seeking ways to tap into its secret machinations, control and master its dark blessing?

Pascal was the first to face in its frightening implications and to expound with the full force of his eloquence: man’s loneliness in the physical universe of modern cosmology. “Cast into the infinite immensity of spaces of which I am ignorant, and which know me not, I am frightened.” “Which know me not”: more than the overawing infinity of cosmic spaces and times, more than the quantitative disproportion, the insignificance of man as a magnitude in this vastness, it is the “silence,” that is, the indifference of this universe to human aspirations—the not-knowing of things human on the part of that within which all things human have preposterously to be enacted—which constitutes the utter loneliness of man in the sum of things. This is the kenoma, the vastation; the emptiness of things, the nothingness of the void. (Jonas, 322) This is the negative of rhetoric – the black hole and limit of thought where the ruin of language and man ends. ENLIGHTENMENT RUINS

Our fascination with the unknown, our uncertainty about reality and the universe, our origins, our future, our place in the scheme of things, etc. is what has driven us for millennia. We have moved through some strange theories concerning both the universe and our place in it throughout this troubling history. The sciences grew out of a deep and abiding hatred and fear of religion and magical or occult practices. It produced the so called secular progressive Enlightenment, a flowering of Reason and rational thought over and against the unruly passions and irrationalism of religion and uncertainty. This search for certainty drove the cycle of thinkers from Descartes through Kant and beyond. Kant would make the deciding move of separating out what is possible to know from what is beyond all thought requiring of all future philosophy and sciences to yield up the phenomena and leave off any pursuit of that mysterious and occult world of the hidden and unknown, the noumenon. So that for two hundred years those that followed in Kant’s wake stayed with in the navigable borders of what could be known through our senses and the categories of the Mind. And this must as Kant would have it all be submitted to the criticism of Reason:

Our age is the age of criticism, to which everything must submit. Religion through its holiness and legislation through its majesty commonly seek to exempt themselves from it. But in this way they excite a just suspicion against themselves, and cannot lay claim to that unfeigned respect that reason grants only to that which has been able to withstand its free and public examination (Axi).

The so called crisis of the Enlightenment that Kant hoped to overcome was at heart an acknowledgement that the sciences, and physics (of his day) based on mechanistic laws that governed the universe and humans undermined the very principles of freedom and reason to which the Enlightenment project tended. What was at stake was the newly assumed ‘authority’ of Reason itself, and it was to answer this that Kant’s Critique of Pure Reason was instigated. “Kant’s main goal is to show that a critique of reason by reason itself, unaided and unrestrained by traditional authorities, establishes a secure and consistent basis for both Newtonian science and traditional morality and religion. In other words, free rational inquiry adequately supports all of these essential human interests and shows them to be mutually consistent. So reason deserves the sovereignty attributed to it by the Enlightenment.”1

In our own time this very notion that self-reflecting reason can turn inward and critique its own movement has itself turned viral, become the heart of contemporary philosophy. The authority of Reason is itself being questioned and undermined. At the heart of studies in consciousness and the neurosciences is a questioning of both reason, philosophy, and the mind-tools that have for millennia been built up to describe the self-reflecting processes of the Mind. Kant wanted to ground philosophy in the principle of sufficient reason, which simply put tells us that for every fact there must be an explanation for why that fact is the case. Among the alleged consequences of the Principle are: the Identity of Indiscernibles, necessitarianism, the existence of a self-necessitated Being (i.e., God), the Principle of Plentitude, and strict naturalism.

The point of the modern neurosciences is that Kant’s Transcendental Subject is blind to its own foundations or ground, it has no access to the given entity of its own formation, the brain. Therefore in our time the notion of freedom, will, reason, and consciousness have come under attack from the naturalists sciences who see these processes that have been for the most part hidden from view, bound to speculative ideas and notions of philosophy for far too long as spelling an end to this long distorted history. With the rise of neuro-imaging technologies scientists are slowly accruing live data concerning the very processes that up to now philosophy only speculated about rather than being able to answer. Yet, for all that the sciences rely on the rhetoric and application of concepts and interpretive strategies that it has borrowed from the very speculative systems it seeks to undermine so that it has found itself at the mercy of its own prolific knowledge.

Some scientists religiously hold that only mathematics can convey the intricacies of those extreme phenomenon that are lifted out of the technological worlds we’ve created, others that the shining weave of images – light-bearers of design and hidden algorithms can break through the empirical screen of things; others still imagine truth is a contingent event, a retroactive agent of our intellect ordering the temporal facticity of time-bound equations. Sciences extrapolate and translate the world from language to the natural in man hoping thereby to repeat what is by nature incomplete and troubling, knowing full well that all the vein communal verification and acceptance of one’s peers is nothing more than the experimental disclosure of an impossible thought. The sciences seek to stabilize what is in motion, lock it down, put it in a void where it can be questioned like a trapped animal, gaze into its secret world as if it could reveal something hidden and away.

Cosmologists have brought us to the edge of the visible and beyond, sought in their mathematical magic the keys to the secrets of time and space, and like those early Shamans of the Greeks have brought back from their escapades in the unknown regions news of strange worlds. They tell of darkness and beginnings, of chaos and order, of the struggles below the threshold of reality as our senses know it; they whisper to us of black holes where light emits music, where stars vanish in a night without morning, of data sparkling on the edge of a whirlpool that sucks the very galaxies in its wake. What scientists see in the mathematical symbols of their art is the merciless order of an incomplete thought, a universe plunging toward oblivion, yet in that very movement seeking a sepulchral existence, a world of dust turned hot and flaming in the birth of light and suns. A realm of flux that gives birth to life on the edge of chaos, that impossible thing that no one as of yet can explicate.

We travel among ancient myths and philosophies, rationalists and atheists as we are seeking to know why these ancients accrued such fanciful tales, why they needed the comfort of strange gods and powers, the inklings of order and chaos and the as if harmony of the spheres; and, why others sought to oppose such worlds with Heimarmene and Ananke, Fate and Necessity. Between the positing of an optimistic realm of light and life, and a negative and pessimistic realm of darkness and death these ancients seemed to war among each other for the soul of the world. Even now in our political myths we see this ancient stream of thought suborning humans to its secret battles, enacting the already depleted designs of its inner necessity. Blindly the parties of humans follow their doom without ever knowing they are repeating the gestures of automated algorithms engineered long ago in the death of stars. END OF PHILOSOPHY?

Philosophy over the course of the twentieth-century divided itself into two major streams of thought: Continental (phenomenological) and the Analytical (language based) philosophies, which have respectively encompassed speculation on the grounds of conscious reasoning from observing either the phenomenological datum of thought, or the linguistic structures that produce thought. Both were like a Mobius strip in which one or the other had a partial truth, but neither alone held it completed. Yet, for all that both kept with Kant’s notion of the subject bound to an object, the notion of consciousness and world bound together in a unique circle or reasoning. This circle of reasoning, or self-reflection became for certain speculative realists (Quentin Meillassoux) a trap. Meillassoux would term it correlationism, “the idea according to which we only ever have access to the correlation between thinking and being, and never to either term considered apart from the other”. 2

This notion that at the heart of the human is a split (dualism) between self and world, thought and being is as old as philosophy itself. From the beginning philosophers have speculated on this fundamental issue of thought and being and how they relate. Those that followed in the wake of Kant took the path of either Idealism (Fichte, Schelling, Hegel, etc.) or Materialism (Schopenhauer, Nietzsche, Marx (under Hegel’s shadow), Bataille, etc.). With the emergence of modern physics and the overturning of mechanistic physics new process philosophies would emerge as Quantum Physics came to the fore with its confrontation of the limits of human thought and mathematics.

Trying to compress this history does little to explain it. The reader will have to follow the threads for herself. For me the issue turns on certain tendencies that seem to come to a head in our contemporary moment. Some philosophers such as Badiou and his disciple Meillassoux turn toward Candorian Set theoretic and mathematics to overcome the linguistic and descriptive barriers of rhetoric and analysis that have bound philosophical speculation since Kant. Others like the Object-Oriented speculators turn toward the structural linguistic roots seeking new rhetorics of description to convey a hint of that which cannot be described. Others like Brassier seek to bring the worlds of thought and world together in the middle-world or concepts believing that it is only in the sphere of conceptuality that we can overcome the split and dualisms that have kept philosophy mired in such dichotomist relations as Idealism/Materialism, etc. for way too long. Then there are the skeptical naturalists like my friend R. Scott Bakker whose Blind Brain Theory harbors the acute critique of all philosophies as misguided, turning away from such speculative systems to renew an empirical tradition that states flatly that humans or for the most part reduced to a functional system of consciousness that is completely blind to its own foundations in the brain’s processes; and, because of this all self-reflection is both mystification and a form of self-delusion for the simple reason that consciousness has literally no access to its internal functions so cannot now or ever describe those processes. He will even stipulate that we don’t even know what we don’t know because the brain has locked us into an evolutionary system built to survive and work with the external environment rather than its own internal processes, and what the brain gives us is only a minimal fraction of this very realm of internal / external relations, and no more. Poverty is our singular state of being. Less is more. We are ignorant of our ignorance, and if we knew just how little we really do not know we’d end it all quickly.

Kant and modern physics agree on one thing: most of reality, ourselves included, is inaccessible (i.e., the realm of noumenon) and hidden away from our prying eyes. Yet, we know this, we are secretly aware of this, and because of this lack of access we strive against it, we seek to overcome these internal and external limits of consciousness and thought through a combination of thought and technology. Most of all we strive to make visible what is inherently invisible to our senses, our empirical functions of consciousness and our external systems of technology. Through mathematics and neuroimaging we seek both empirical, theoretic and indirect access to what is hidden (occult) from us. EXCESS AND CONSUMPTION

Others like Bataille and Land seek to formulate a dehumanization of self and nature, seeking to impersonalize our notions of both internal and external forces, contributing to a strict atheological cosmology. One that is indifferent both to human thought and affective relations. For Nick Land the only foundation is no foundation at all, rather a ruthless fatalism; one devoid of human intentions, decisions, morality, or that illusionary icon of all idealisms, human freedom. Instead as he warns us we must become alien and estranged from what has up too now been termed the ‘human’. Following Nietzsche, Freud, and Bataille he squanders, sacrifices, and exuberantly wastes the excess of the human through an economy of consumption and libidinal excess. His dark atheological cosmology situates itself within the current paradigm of our universe that is a seeming ocean of dark energy and dark matter. One that is impersonal and indifferent to both human thought and aspirations.

In the popular imagination one sees in such strange phenomenon as the paranormal and the amalgam of horror and ghost tales, as well as shows now prevalent in TV and movies a popular investigation of our fears. This underbelly of literature and film over the past couple hundred years as if in direct opposition to the Enlightenments project of a controlled and reasonable world seems to have become in our time a deluge. The themes of gothic horror and dread in such writers as H.P. Lovecraft, Thomas Ligotti, and science fiction writers like Philip K. Dick and Stanislaw Lem help contribute to current speculative philosophies that seek new rhetorical strategies and support for understanding the emergence of the noumenal and hidden, the base matter below the threshold of the known and objective worlds of the sciences. Many of these tales uncover a negative rhetoric of desire based on eroticism and death, twin progeny of a anhedonic cosmos of delirium.

Jacques Lacarrière in his short meditation on the ancient Gnostics offered his personal estimation of these strange and bewildering texts that have come down to us across the millennium of a bygone world that was slowly obliterated by the institution of Christian Paternalism that installed itself in ancient Rome and ruled Western Civilization through its spiritual hold from the fall of Rome till the Enlightenment. With the uncovering of the Nag Hammadi works and their slow translation over the past few decades we are becoming more and more awakened to this alternative view of this now lost history. For Lacarrière it came down to a cosmic and political battle against false realities and tyrants both earthly and cosmic:

My conviction goes still further: I believe that these paths show us the only possible way, the only way of acting in the face of the mysteries of the world. One must try everything, experience everything, unveil everything, in order to strip man down to his naked condition; to `defrock’ him of his organic, psychic, social, and historic trappings; to decondition him entirely so that he may regain what is called by some his choice, by others his destiny. As I write this word, decondition, I perceive that I am reaching the very heart of Gnostic doctrine. No knowledge, no serious contemplation, no valid choice is possible until man has shaken himself free of everything that effects his conditioning, at every level of his existence. And these techniques which so scandalize the uninitiated, whether they be licentious or ascetic, this consumption and consummation of organic and psychic fires-sperm and desire-these violations of all the rules and social conventions exist for one single, solitary purpose: to be the brutal and radical means of stripping man of his mental and bodily habits, awakening in him his sleeping being and shaking off the alienating torpor of the soul.

As Kirsten J. Grimstad describes it in her study of Thomas Mann and Gnosticism in the Cultural Matrix of His Time: “Gnostic motifs and sensibility began cropping up in the fiction of contemporary authors Herman Melville, Charles Baudelaire, Huysmans, W.B. Yeats, Ezra Pound, Antonin Artaud, Franz Kafka, Walker Percy, Flannery O’Conner, William Gaddis, and Thomas Pynchon, Vladimir Nabokov, Herman Hesse, Lawrence Durrell, Jorge Luis Borges as well as in science fiction novels by Philip K. Dick, to name just a few well known examples noted in critical studies. (see notes) She argues that the modern cultural movement known as the religion of art (aestheticism, decadence, late romanticism) rekindled a culturally subversive Gnostic sensibility that was expressed in an extremist revolt against modernity, reiterating the Gnostic revolt against the cosmos.

Like the Divine Marquise (Sade) the Gnostic’s first task was to use up the substance of evil by combatting it with its own weapons, by practicing what one might call a homeopathic asceticism. Since we are surrounded and pulverized by evil, let us exhaust it by committing it; let us stoke up the forbidden fires in order to burn them out and reduce them to ashes; let us consummate by consuming (and there is only one step, or three letters, between `consuming’ and `consummating’) the inherent corruption of the material world. ( Lacarrière, p. 59) Explaining it in detail:

If the soul during the course of this life has not succeeded in experiencing everything before death, if there still remain certain forbidden areas it has not penetrated, some part of evil it has yet to consume, then it must live again in another body until `it has acquitted its duty to all the masters of the cosmos.’ This threat-which is virtually a curse-hanging over the future lives of the disciple must certainly have incited him to take the plunge straight away, to `have done with’ these masters of the cosmos in his present life, to `wipe out’ his debts to evil at a single stroke – that is to say, in a single existence. Contrary to what one might be tempted to make of this idea, it is a question of asceticism and not of indulgence in pleasure. ( Lacarrière, p. 60)

The notion of pushing the limits of every extreme to excess by breaking every law, every taboo, every form of licentious act by a consuming act of excess, and a consummation of evil in this life seems the impossible task of our time. Ultimately is it not to overcome the self-imposed limits of thought that since Kant have locked us into a prison both philosophical, economic, artistic, and normative? Have we now finally come to the point that the most extreme forms of active nihilism are forcing us to adopt even more extreme and – must one dare say it, acosmic nihilisms? Land tells us that such thinking is “less concerned with propositions than with punctures; hacking at the flood-gates that protect civilization from a deluge of impersonal energy” (p. xxi).3

ARCHONS AND THE IRON PRISON

In his widely regarded survey of Gnosticism Hans Jonas once described the gnostic cosmology:

The universe, the domain of the Archons, is like a vast prison whose innermost dungeon is the earth, the scene of man’s life. Around and above it the cosmic spheres are ranged like concentric enclosing shells. Most frequently there are the seven spheres of the planets surrounded by the eighth, that of the fixed stars. There was, however, a tendency to multiply the structures and make the scheme more and more extensive: Basilides counted no fewer than 365 “heavens.” The religious significance of this cosmic architecture lies in the idea that everything which intervenes between here and the beyond serves to separate man from God, not merely by spatial distance but through active demonic force. Thus the vastness and multiplicity of the cosmic system express the degree to which man is removed from God.4

The Archons collectively rule over the world, and each individually in his sphere is a warder of the cosmic prison. Their tyrannical world-rule is called heimarmene, universal Fate, a concept taken over from astrology but now tinged with the gnostic anti-cosmic spirit. In its physical aspect this rule is the law of nature; in its psychical aspect, which includes for instance the institution and enforcement of the Mosaic Law, it aims at the enslavement of man. As guardian of his sphere, each Archon bars the passage to the souls that seek to ascend after death, in order to prevent their escape from the world and their return to God. The Archons are also the creators of the world, except where this role is reserved for their leader, who then has the name of demiurge (the world-artificer in Plato’s Timaeus) and is often painted with the distorted features of the Old Testament God. (Jonas)

Georges Bataille would say of these ancient systems: “It is possible to see as a leitmotif of Gnosticism the conception of matter as an active principle having its own eternal autonomous existence as darkness (which would not be simply the absence of light, but the monstrous archontes revealed by this absence), and as evil (which would not be the absence of good, but a creative action).”5 As Jonas would affirm the world is the product, and even the embodiment, of the negative of knowledge. What it reveals is unenlightened and therefore malignant force, proceeding from the spirit of self-assertive power, from the will to rule and coerce. The mindlessness of this will is the spirit of the world, which bears no relation to understanding and love. The laws of the universe are the laws of this rule, and not of divine wisdom. Power thus becomes the chief aspect of the cosmos, and its inner essence is ignorance (agnosia). To this, the positive complement is that the essence of man is knowledge—knowledge of self and of God: this determines his situation as that of the potentially knowing in the midst of the unknowing, of light in the midst of darkness, and this relation is at the bottom of his being alien, without companionship in the dark vastness of the universe. (p. 327-328)

For the Greeks cosmos, was the seat of order and harmony; but for the Gnostics this same system was still an order — but order with a vengeance, alien to man’s aspirations. Its recognition is compounded of fear and disrespect, of trembling and defiance. The blemish of nature lies not in any deficiency of order, but in the all too pervading completeness of it. Far from being chaos, the creation of the demiurge, unenlightened as it is, is still a system of law. But cosmic law, once worshiped as the expression of a reason with which man’s reason can communicate in the act of cognition, is now seen only in its aspect of compulsion which thwarts man’s freedom. The cosmic logos of the Stoics, which was identified with providence, is replaced by heimarmene, oppressive cosmic fate. (Jonas, 328)

This fatum is dispensed by the planets, or the stars in general, the personified exponents of the rigid and hostile law of the universe. The change in the emotional content of the term cosmos is nowhere better symbolized than in this depreciation of the formerly most divine part of the visible world, the celestial spheres. The starry sky—to the Greeks since Pythagoras the purest embodiment of reason in the sensible universe, and the guarantor of its harmony— now stared man in the face with the fixed glare of alien power and necessity. No longer his kindred, yet powerful as before, the stars have become tyrants—feared but at the same time despised, because they are lower than man. (Jonas, 328) NICK LAND AS DEMON OF TIME

Land in a moment of sarcasm aligns himself with the mythos of the archons in a parodic respite: “I slunk into Hell like a verminous cur, accompanied by a wanderer of an altogether more celestial aspect. According to the Sikh religion humans are the masks of angels and demons, and my own infernal lineaments bear little ambiguity (everywhere I go the shadows thicken). (Land, xxii) One wonders who the accompanying wanderer is? That Land would have no truck with revitalizations of Gnostic religion, no harboring of escape from the Iron Prison of Time, no salvation mythology of gnosis with acosmic gods or God is I think an assured assessment. Land is a culmination of those atheological masters who would push the extremes of active nihilism beyond the limits of the human. But where does this leave us? For Land the answer is simple: nowhere. Death is our lot, and the sooner the better.

If Land has a similarity to the ancient Gnostics it is one that requires of us the repudiation of even the acosmic God and his knowledge, instead for Land it is humanism itself that is the enemy of man:

“Humanism (capitalist patriarchy) is the same thing as our imprisonment. Trapped in the maze, treading the same weary round. Round and round in the garbage. Round… round and round (God is a scratched record), even when we think we are progressing, knowing more. Round and round, missing the sacred, until it drives you completely out of your mind. But at least we die. (Land, 209)

Trapped in false systems of thought, bound to a cosmic madhouse, circling in a repetitious universe of garbage in which the sacred itself has been expunged. Is this not the beginnings of a gnosis? Nietzsche indicated the root of the nihilistic situation in the phrase “God is dead,” meaning primarily the Christian God. The Gnostics, if asked to summarize similarly the metaphysical basis of their own nihilism, could have said only “the God of the cosmos is dead”—is dead, that is, as a god, has ceased to be divine for us and therefore to afford the lodestar for our lives. Admittedly the catastrophe in this case is less comprehensive and thus less irremediable, but the vacuum that was left, even if not so bottomless, was felt no less keenly. To Nietzsche the meaning of nihilism is that “the highest values become devaluated” (or “invalidated”), and the cause of this devaluation is “the insight that we have not the slightest justification for positing a beyond, or an ‘in itself of things, which is ‘divine,’ which is morality in person.” This statement taken with that about the death of God, bears out Heidegger’s contention that “the names God and Christian God are in Nietzsche’s thought used to denote the transcendental (supra-sensible) world in general. God is the name for the realm of ideas and ideals” (Holzwege, p. 199).7 Since it is from this realm alone that any sanction for values can derive, its vanishing, that is, the “death of God,” means not only the actual devaluation of highest values, but the loss of the very possibility of obligatory values as such. To quote Heidegger’s interpretation of Nietzsche, “The phrase ‘God is dead’ means that the supra-sensible world is without effective force.”

In such a cosmos where law, nomos, and transcendence have withdrawn from any normative relation to the world reality becomes emptied of its connections to the human, devoid of its traces, unbound from its old hallucinatory power and is suddenly forced to divulge its hidden existence as pure horror. The point being there remains no external authority, no framework, ground, or foundation for human thought and meaning. We are left to ourselves, thrown back upon our ignorance without hope or recourse. Reality disperses its illusions and the void hiding in the veil of nothingness releases the chaos stirring below the threshold, and the tensions within this flux of consume us like a black hole at the center of our turbulent being. A being without center or circumference, without substance or essence; a being that is itself at war with nonbeing, an interminable movement that gravitates toward that final flame of extinction.

Land is one of those messengers from Hell – a zone of terror and energia where the darkness becomes light, light darkness; an antinomian realm where angels and demons where the masks of humans. As he states it each “day that I remain trapped in the garbage I forget a little more of what it is to cross the line, but even forgetting is dying, and dying is crossing the line.” (Land, 210) As Jonas will remark there is a distinction to all modern parallels: in the gnostic formula it is understood that, though thrown into temporality, we had an origin in eternity, and so also have an aim in eternity. This places the innercosmic nihilism of the Gnosis against a metaphysical background which is entirely absent from its modern counterpart. (Jonas, 335) In Land the only background is that there is none, there is only the “zero of words” and, as he will admonish us, “nor are words about words” (Land, 210). For Land there is only poetry:

to sleep hanging upside down

in a barn sheltered from the day and then when it gets dark flapping out

The disruption between man and total reality is at the bottom of virulent nihilism as it is with Gnosticism. The illogicality of the rupture, that is, of a dualism without metaphysics – an atheology, makes its fact no less real, nor its seeming alternative any more acceptable: the stare at isolated selfhood, to which it condemns man, may wish to exchange itself for a monistic naturalism which, along with the rupture, would abolish also the idea of man as man. “Between that Scylla and this her twin Charybdis, the modern mind hovers.” (Jonas, 340) Our contemporary cosmologists wrap us in an ocean of dark matter and dark energy of which we know little, and steeped as we are in mythologies of light and baryon matter we assume in our ignorance too much. Our knowledge and thought have entered the moment of limits, a time when humans must move beyond the human, enter a new stage of immanent metamorphosis, undergo a transition to a new state, a happening. Else die. The Gnostics and Land agree that this universe is an impersonal system of energetic forces, what they disagree is on the notion of Exit. Both agree the cosmos is a garbage heap, the body of a dead or dying demiurge – though Land would expunge any anthropomorphisms. For the Gnostics exit was to affirm the gnosis “What makes us free is the Gnosis of who we were of what we have become of where we were of wherein we have been thrown of whereto we are hastening of what we are being freed of what birth really is of what rebirth really is” (Gnostic credo from the second century C.E.) As Harold Bloom would explicate:

What the Gnosis tells us is that time, which degrades, itself is the product of a divine degradation, a failure within God. The crisis within the Pleroma, the disruption in the original Fullness, had to be mutual: when we crashed down into this world made by the inept angels, then God crashed also, coming down not with us, but in some stranger sphere, impossibly remote. There are (at least) two kenomas, two cosmological emptinesses: our world, this world, and the invisible spheres also formed in fright, as Herman Melville says in his very Gnostic masterpiece, Moby-Dick. In those waste places, God now wanders, himself an alien, a stranger, an exile, even as we wander here. Time, an envious shadow (as the Gnostic poet Shelley called it) fell from the Fullness onto our world. An equally envious shadow, a nameless one, hovers across the wandering God of the Abyss, not only cut off from us, as we are from him, but as helpless without us as we are without him.6

What Bloom and many commentators of this Valentinian myth seem reluctant to ask is: Why is this acosmic God so powerless? Why has he fallen into his own kenoma? Why has he lost himself in his own degraded cosmic catastrophe? Of course there is no answer but one: he wanted to die and couldn’t, his eternal life had become impossible, and the only possible escape, exit was to purge himself of his own degradation: the emptiness of things is this divine degradation, at least for the Valentinian gnosis. Yet, this does not explain why this supposed acosmic God is so helpless to bridge the gulf of shadows between us and him. The mythus would have it that we are the ‘tears of god’ that we are his forlornness, and it is only by way of sacrifice and a deeper corruption that we can begin to burn through the cold wall of indifference that is God himself. The Body of Evil that is this dead universe is that degradation, that evil which for Bataille like Land is not a moral evil, but rather the energetic derision of a cosmic agon, the seething sea of corruption that is none other than God himself, his Dead Body. Or as Joyce would say “Dog’s Body”. All metaphors and poetry of the inexplicable indifference of things…

The notion that our universe came about through a cosmic catastrophe (“war in heaven”) which left both God and Man separated in two realms of kenoma, or degradation and emptiness in which both are aliens locked in prisons founded by a demiurgic takeover is both strange and estranging. Land knowingly or unknowingly takes bits of this strangeness and reduces the enemy to the system of Humanism and Personalism while opting at the only salvation left: the total destruction of this cosmos by way of utter annihilation.

Maybe William Blake said it best:

Tyger Tyger burning bright,

In the forests of the night: What immortal hand or eye, Dare frame thy fearful symmetry?

For Blake, a natural gnostic, all tigers were framed by an impersonal order that had no thought about tigers or humans; an indifferent system of wheels within wheels that was both mindless and without thought. The poet Blake, emphasizes the importance of the human imagination. Systems of thought, philosophies or religions, when separated from men, destroy what is human. Like many of his era Imagination, not Intellect or Passion was the central aspect to man’s exit from the horrors of universal impersonalism that surrounded him on all sides. All gods, religions, philosophies resided in the human breast, but we had externalized them to the point that now they’d escaped us and were ruling over us like blind unreasoning forces. “The Visions of Eternity, by reason of narrowed perceptions, / Are become weak Visions of Time & Space, fix’d into furrows of death.” We wander in a zone of pure death and have forgotten our true home. This hellish paradise is both our glory and our ultimate fate, born of catastrophe we die the lives of angels, and live the lives of demons.

Yet, for Land, this, too, is myth and wishful thinking. There is no escape from this kenoma, only annihilation. Land has taken despair and turned it into a joyful acceptance of Nietzschean “amor fati” – the eternal return is the only exit we can know, our fatum. Yet, unlike the Cosmos of the ancient Greeks where harmony and order ruled, in Land’s Cosmos there is nothing but the impersonal energetic forces of a groundless ground immanent to all degradation and corruption, the eternal return of chaos in motion and happening. For Land if the Universe is an abortion, man is it primal advocate; man is the abortion of a fetid thought.

“He who fights with monsters should look to it that he himself does not become a monster. And when you gaze long into an abyss the abyss also gazes into you.”

— Nietzsche

Philosophical speculation gives way to the empirical machinations of artificial intelligence, algorithmic calculations and the impersonal data grafts of an indifferent world of technology and inhuman thought. As philosophy gives way to artificial life we begin to access the inhuman future of those ancient angelic intelligences for whom the universe is an infinite mechanism of interconnecting engines of creation and destruction, a veritable consuming machine whose blind machinations is indifferent and beyond appeal. As biological man moves beyond the limits of his organic existence, shaping his intelligence to the iron law of this indifferent cosmos he will discover a deeper and more infinite putrefaction; the slow metamorphosis from human to inhuman and artificial existence will not give him the freedom he expects, but will instead enmesh him mercilessly into the necromantic arts of a vast and indomitable system of emptiness without end. Locked into the dark folds of this seething sea of energy he will spend out his eternity in the wastelands of oblivion, a mind hollowed out by its dreams of reason, it will know only the tumescence of an engorged festival of death; a death, cold and indifferent, solitary and emptied of its last vestiges of human affect, immortal at last.

Irony awakens death from sleep. If one could reduce the portrayal of Land to one aphoristic ensemble, then one must depict him as a member of that dark tribe who sees in the modern veneration of the intellect a blueprint for spiritual gulags and the corruption of the world. Indeed, for Land, man’s task is to wash himself in the black cesspools of dead stars, for futility is not hopelessness; futility is a reward for those seeking to rid themselves of the epidemic of life and the virus of hope. Probably, this image best befits the man who many might describe as a fanatic without any convictions a stranded accident in the cosmos who casts a nostalgic gaze towards the abyss beyond which nothing remains but nothingness and absolute zero, a terminal zone of pure annihilation.

Taken from:

by Himanshu Damle The first step of deriving General Relativity and particle physics from a common fundamental source may lie within the quantization of the classical string action. At a given momentum, quantized strings exist only at discrete energy levels, each level containing a finite number of string states, or particle types. There are huge energy gaps between each level, which means that the directly observable particles belong to a small subset of string vibrations. In principle, a string has harmonic frequency modes ad infinitum. However, the masses of the corresponding particles get larger, and decay to lighter particles all the quicker. Most importantly, the ground energy state of the string contains a massless, spin-two particle. There are no higher spin particles, which is fortunate since their presence would ruin the consistency of the theory. The presence of a massless spin-two particle is undesirable if string theory has the limited goal of explaining hadronic interactions. This had been the initial intention. However, attempts at a quantum field theoretic description of gravity had shown that the force-carrier of gravity, known as the graviton, had to be a massless spin-two particle. Thus, in string theory’s comeback as a potential “theory of everything,” a curse turns into a blessing. Once again, as with the case of supersymmetry and supergravity, we have the astonishing result that quantum considerations require the existence of gravity! From this vantage point, right from the start the quantum divergences of gravity are swept away by the extended string. Rather than being mutually exclusive, as it seems at first sight, quantum physics and gravitation have a symbiotic relationship. This reinforces the idea that quantum gravity may be a mandatory step towards the unification of all forces. Unfortunately, the ground state energy level also includes negative-mass particles, known as tachyons. Such particles have light speed as their limiting minimum speed, thus violating causality. Tachyonic particles generally suggest an instability, or possibly even an inconsistency, in a theory. Since tachyons have negative mass, an interaction involving finite input energy could result in particles of arbitrarily high energies together with arbitrarily many tachyons. There is no limit to the number of such processes, thus preventing a perturbative understanding of the theory. An additional problem is that the string states only include bosonic particles. However, it is known that nature certainly contains fermions, such as electrons and quarks. Since supersymmetry is the invariance of a theory under the interchange of bosons and fermions, it may come as no surprise, post priori, that this is the key to resolving the second issue. As it turns out, the bosonic sector of the theory corresponds to the spacetime coordinates of a string, from the point of view of the conformal field theory living on the string worldvolume. This means that the additional fields are fermionic, so that the particle spectrum can potentially include all observable particles. In addition, the lowest energy level of a supersymmetric string is naturally massless, which eliminates the unwanted tachyons from the theory. The inclusion of supersymmetry has some additional bonuses. Firstly, supersymmetry enforces the cancellation of zero-point energies between the bosonic and fermionic sectors. Since gravity couples to all energy, if these zero-point energies were not canceled, as in the case of non-supersymmetric particle physics, then they would have an enormous contribution to the cosmological constant. This would disagree with the observed cosmological constant being very close to zero, on the positive side, relative to the energy scales of particle physics. Also, the weak, strong and electromagnetic couplings of the Standard Model differ by several orders of magnitude at low energies. However, at high energies, the couplings take on almost the same value, almost but not quite. It turns out that a supersymmetric extension of the Standard Model appears to render the values of the couplings identical at approximately 1016 GeV. This may be the manifestation of the fundamental unity of forces. It would appear that the “bottom-up” approach to unification is winning. That is, gravitation arises from the quantization of strings. To put it another way, supergravity is the low-energy limit of string theory, and has General Relativity as its own low-energy limit. taken from: by Himanshu Damle String theory, which promises to give an all-encompassing, nomologically unified description of all interactions did not even lead to any unambiguous solutions to the multitude of explanative desiderata of the standard model of quantum field theory: the determination of its specific gauge invariances, broken symmetries and particle generations as well as its 20 or more free parameters, the chirality of matter particles, etc. String theory does at least give an explanation for the existence and for the number of particle generations. The latter is determined by the topology of the compactified additional spatial dimensions of string theory; their topology determines the structure of the possible oscillation spectra. The number of particle generations is identical to half the absolute value of the Euler number of the compact Calabi-Yau topology. But, because it is completely unclear which topology should be assumed for the compact space, there are no definitive results. This ambiguity is part of the vacuum selection problem; there are probably more than 10100 alternative scenarios in the so-called string landscape. Moreover all concrete models, deliberately chosen and analyzed, lead to generation numbers much too big. There are phenomenological indications that the number of particle generations can not exceed three. String theory admits generation numbers between three and 480. Attempts at a concrete solution of the relevant external problems (and explanative desiderata) either did not take place, or they did not show any results, or they led to escalating ambiguities and finally got drowned completely in the string landscape scenario: the recently developed insight that string theory obviously does not lead to a unique description of nature, but describes an immense number of nomologically, physically and phenomenologically different worlds with different symmetries, parameter values, and values of the cosmological constant. String theory seems to be by far too much preoccupied with its internal conceptual and mathematical problems to be able to find concrete solutions to the relevant external physical problems. It is almost completely dominated by internal consistency constraints. It is not the fact that we are living in a ten-dimensional world which forces string theory to a ten-dimensional description. It is that perturbative string theories are only anomaly-free in ten dimensions; and they contain gravitons only in a ten-dimensional formulation. The resulting question, how the four-dimensional spacetime of phenomenology comes off from ten-dimensional perturbative string theories (or its eleven-dimensional non-perturbative extension: the mysterious, not yet existing M theory), led to the compactification idea and to the braneworld scenarios, and from there to further internal problems. It is not the fact that empirical indications for supersymmetry were found, that forces consistent string theories to include supersymmetry. Without supersymmetry, string theory has no fermions and no chirality, but there are tachyons which make the vacuum instable; and supersymmetry has certain conceptual advantages: it leads very probably to the finiteness of the perturbation series, thereby avoiding the problem of non-renormalizability which haunted all former attempts at a quantization of gravity; and there is a close relation between supersymmetry and Poincaré invariance which seems reasonable for quantum gravity. But it is clear that not all conceptual advantages are necessarily part of nature, as the example of the elegant, but unsuccessful Grand Unified Theories demonstrates. Apart from its ten (or eleven) dimensions and the inclusion of supersymmetry, both have more or less the character of only conceptually, but not empirically motivated ad-hoc assumptions. String theory consists of a rather careful adaptation of the mathematical and model-theoretical apparatus of perturbative quantum field theory to the quantized, one-dimensionally extended, oscillating string (and, finally, of a minimal extension of its methods into the non-perturbative regime for which the declarations of intent exceed by far the conceptual successes). Without any empirical data transcending the context of our established theories, there remains for string theory only the minimal conceptual integration of basic parts of the phenomenology already reproduced by these established theories. And a significant component of this phenomenology, namely the phenomenology of gravitation, was already used up in the selection of string theory as an interesting approach to quantum gravity. Only, because string theory, containing gravitons as string states, reproduces in a certain way the phenomenology of gravitation, it is taken seriously. Taken from:

by Himanshu Damle

DATACRYPTO is a web crawler/scraper class of software that systematically archives websites and extracts information from them. Once a cryptomarket has been identified, DATACRYPTO is set up to log in to the market and download its contents, beginning at the web page fixed by the researchers (typically the homepage). After downloading that page, DATACRYPTO parses it for hyperlinks to other pages hosted on the same market and follows each, adding new hyperlinks encountered, and visiting and downloading these, until no new pages are found. This process is referred to as web crawling. DATACRYPTO then switches from crawler to scraper mode, extracting information from the pages it has downloaded into a single database.

loading...

One challenge connected to crawling cryptomarkets arises when, despite appearances to the contrary, the crawler has indexed only a subset of a marketplace’s web pages. This problem is particularly exacerbated by sluggish download speeds on the Tor network which, combined with marketplace downtime, may prevent DATACRYPTO from completing the crawl of a cryptomarket. DATACRYPTO was designed to prevent partial marketplace crawls through its ‘state-aware’ capability, meaning that the result of each page request is analysed and logged by the software. In the event of service disruptions on the marketplace or on the Tor network, DATACRYPTO pauses and then attempts to continue its crawl a few minutes later. If a request for a page returns a different page (e.g. asking for a listing page and receiving the home page of the cryptomarket), the request is marked as failed, with each crawl tallying failed page requests.

DATACRYPTO is programmed for each market to extract relevant information connected to listings and vendors, which is then collected into a single database:

loading...

DATACRYPTO is not the first crawler to mirror the dark web, but is novel in its ability to pull information from a variety of cryptomarkets at once, despite differences in page structure and naming conventions across sites. For example, “$…” on one market may give you the price of a listing. On another market, price might be signified by “VALUE…” or “PRICE…” instead.

Researchers who want to create a similar tool to gather data through crawling the web should detail which information exactly they would like to extract. When building a web crawler it is, for example, very important to carefully study the structure and characteristics of the websites to be mirrored. Before setting the crawler loose, ensure that it extracts and parses correct and complete information. Because the process of building a crawler-tool like DATACRYPTO can be costly and time consuming, it is also important to anticipate on future data needs, and build in capabilities to extract that kind of data later on, so no large future modifications are necessary.

Building a complex tool like DATACRYPTO is no easy feat. The crawler needs to be able to copy pages, but also stealthily get around CAPTCHAs and log itself in onto the TOR server. Due to their bulkiness, web crawlers can place a heavy burden on a website’s server, and are easily detected due to their repetitive pattern moving between pages. Site administrators are therefore not afraid to IP-ban badly designed crawlers from their sites.

Taken from:

|

Science&TechnologyArchives

March 2020

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed