|

by Steven Craig Hickman

Perhaps it seems that I have said too much about the Red Tower, and perhaps it has sounded far too strange. Do not think that I am unaware of such things. But as I have noted throughout this document, I am only repeating what I have heard. I myself have never seen the Red Tower—no one ever has, and possibly no one ever will.

—Thomas Ligotti, The Nightmare Factory

Thomas Ligotti does not see the world as you and I. He does not see the world at all. Rather he envisions another, separate realm of description, a realm that sits somewhere between the interstices of the visible and invisible, a twilight zone of shifting semblances, echoes of our world. Each of his stories is neither a window onto that realm, nor a mirror of its dark recesses but rather a promise of nightmares that travel among us like revenants seeking a habitation. Reading his stories awakens not the truth of this mad world, but shapes our psyches toward the malformed madness that surrounds us always. For we inhabit the secure regions of a fake world, a collective hallucination of the universal decay not knowing or wishing to know the truth in which we live and have our being.

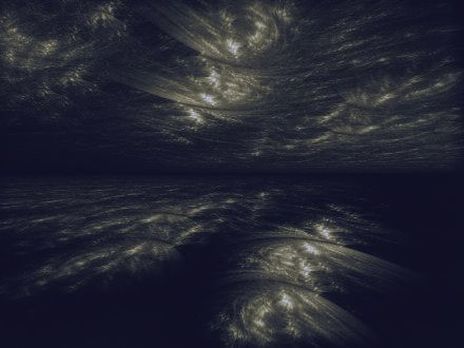

The security filters that wipe out the traces of the real world are lacking in Ligotti. The system of tried and tested traps that keep us safely out of the nightmare lands never took hold of Ligotti’s keen mind. Rather he inhabits a hedge world, a fence between the realms of the noumenal and phenomenal, appearance and reality. But it is not a dual world. There is no separate realm beyond this one, only the “mind-made manacles” as William Blake called them of the self-imposed collective security regimes we call the human realm. Only the filters of language, culture, and civilization protect us from the dark truth of the universe in all its nightmare glory. Speaking of the dark marvels of our blank universe of entropic decay, of the endless sea of blackness surrounding those small pools of light in the starry firmament, Ligotti contemplates creation:

Dreaming upon the grayish desolation of that landscape, I also find it quite easy to imagine that there might have occurred a lapse in the monumental tedium, a spontaneous and inexplicable impulse to deviate from a dreary perfection, perhaps even an unconquerable desire to risk a move toward a tempting defectiveness.

For Ligotti the universe is not so much a place where gods or God, demons or Devils vie for the souls of humans, but is a realm of impersonal forces that have neither will nor intelligence. A realm of malevolence only in the sense that it cares not one iota for its progeny, of its endless experiments, its defective and deviant children. It only knows movement and change, process and the swerve away from perfection. This is our universe, as Wallace Stevens once said so eloquently in the Poem of Our Climate,

There would still remain the never-resting mind,

So that one would want to escape, come back To what had been so long composed. The imperfect is our paradise. Note that, in this bitterness, delight, Since the imperfect is so hot in us, Lies in flawed words and stubborn sounds.

Between entropy decay and negentropic creativity we move in a dark vitality of organic and inorganic motion, our minds blessed or cursed with awareness. And, yet, most of us are happily forgetful of our state of being and becoming, unaware of the murderous perfection against which our flawed lives labour. We are blessed with forgetfulness and sleep, oblivious of the machinery of creation that seeks our total annihilation. For life is a rift in the calm perfection of eternity, a rupture in the quietude of perfection that is the endless sea of nothingness. We are the enemies of this dead realm of endless night and universal decay. With us an awareness of the mindless operations of a negentropic process and movement to tilt the balance of the universal apathy was begun. We are the children of a corrupt thought, an imperfect and flawed creation that should not have been. And all the forces of perfection have been set loose to entrap us and bring the ancient curse to an end.

Speaking of this Ligotti will remind us that

An attempt was made to reclaim the Red Tower, or at least to draw it back toward the formless origins of its being. I am referring, of course, to that show of force which resulted in the evaporation of the factory’s dense arsenal of machinery. Each of the three stories of the Red Tower had been cleaned out, purged of its offending means of manufacturing novelty items, and the part of the factory that rose above the ground was left to fall into ruins.

Yes, we are an afterthought, a mere copy of a copy, experimental actors in a universal factory that has gone through many editions, fought many wars before us, many worlds. Many universes of manufactured realities have come before ours. We are not special in this regard, but are instead the next in a long line of novelty products of a process that is mindless in intent, yet long in its devious and malevolent course toward imperfection. Or as Ligotti puts it:

Dreaming upon the grayish desolation of that landscape, I also find it quite easy to imagine that there might have occurred a lapse in the monumental tedium, a spontaneous and inexplicable impulse to deviate from a dreary perfection, perhaps even an unconquerable desire to risk a move toward a tempting defectiveness. As a concession to this impulse or desire out of nowhere, as a minimal surrender, a creation took place and a structure took form where there had been nothing of its kind before. I picture it, at its inception, as a barely discernible irruption in the landscape, a mere sketch of an edifice, possibly translucent when making its first appearance, a gray density rising in the grayness, embossed upon it in a most tasteful and harmonious design. But such structures or creations have their own desires, their own destinies to fulfil, their own mysteries and mechanisms which they must follow at whatever risk.

Our world is that deviation, that experimental factory in a gray sea of desolation, a site where novelties of a “hyper-organic” variety are endlessly produced with a desire of their own. Describing the nightmare of organicicity Ligotti offers us a picture of the machinic system of our planetary life

On the one hand, they manifested an intense vitality in all aspects of their form and function; on the other hand, and simultaneously, they manifested an ineluctable element of decay in these same areas. That is to say that each of these hyper-organisms, even as they scintillated with an obscene degree of vital impulses, also, and at the same time, had degeneracy and death written deeply upon them. In accord with a tradition of dumbstruck insanity, it seems the less said about these offspring of the birthing graves, or any similar creations, the better. I myself have been almost entirely restricted to a state of seething speculation concerning the luscious particularities of all hyper-organic phenomena produced in the subterranean graveyard of the Red Tower.

We know nothing of the teller of the tales, only that everything he describes is at second hand, a mere reflection of a reflection, a regurgitated fragment from the demented crew of the factory who have all gone insane: “I am only repeating what I have heard. I myself have never seen the Red Tower—no one ever has, and possibly no one ever will.”

Bound to our illusions, safely tucked away in the collective madness of our “human security regimes” (Nick Land), we catch only glimpses of the blood soaked towers of the factory of the universal decay surrounding us. Ligotti, unlike us, lives in this place of no place, burdened with the truth, with the sight of the universe as it is, unblinkered by the rose tented glasses of our cultural machinery. Ligotti sees into things, and what he’s discovered is the malevolence of a endless imperfection that is gnawing away at the perfection of nothingness. Ligotti admits he has no access to the machinery of the world, only its dire reflection and echo in others who have gone insane within its enclosed factory and assemblage. Echoing the mad echoes of the insane he repeats the gestures of the unknown and unknowable in the language of a decaying empire of mind. To read Ligotti is to sift through the cinders of a decaying and dying earth, to listen to the morbidity of our birthing pains, to view “the gray and featureless landscapes” of our mundane lives as we spend our days in mindless oblivion of the dark worlds that encompass us.

Broken in mind and body, caught in the mesh of a world in decay and imperfection, Ligotti sends us messages from the asylums of solitude, a figure in the dark of our times, an outrider from the hells of our impersonal and indifferent chaosmos. His eyes gaze upon that which is both the ill-fame night and the daily terror of his short life. He gifts us with his nightmares, and suffers for us the cold extremity of those stellar regions of the soul we dare not enter. Bound to the wheel of horror he discovers the tenuous threads that provide us guideposts and liminal puzzles from the emptiness of which we are made. In an essay on Heidegger, Nick Land once remarked that “Return, which is perhaps the crucial thought of modernity, must now be read elsewhere. The dissolution of humanism is stripped even of the terminology which veils collapse in the mask of theoretical mastery. It must be hazarded to poetry.”1 In Ligotti the hazard is the poetry of the mind facing the contours of a universe of corruption that is in itself beautiful as the cold moon glowing across the blue inflamed eyes of a stranger, her gaze alight with the suns dying embers and the shifting afterglow of the moons bone smile.

Or, as Ligotti’s interlocutor says in summation:

I must keep still and listen for them; I must keep quiet for a terrifying moment. Then I will hear the sounds of the factory starting up its operations once more. Then I will be able to speak again of the Red Tower.

Listen for the machinery of creation to start up again, to hear the martialing of new universes arising out of the void; for the blinding light of annihilation that will keep step with the logic of purification and transcendence that has trapped us in this dark cave of mind till language, man, and creation are folded back into that immanent world from which they were sprung. Then we, too, might begin speaking the words that will produce in us that which is more than ourselves.

taken from:

0 Comments

by Steven Craig Hickman “Metaphysical revelations begin only when one’s superficial equilibrium starts to totter…” – E.M. Cioran “…the consolation of horror in art is that it actually intensifies our panic, loudens it on the sounding-board of our horror-hollowed hearts, turns terror up full blast, all the while reaching for that perfect and deafening amplitude at which we may dance to the bizarre music of our own misery.” – Thomas Ligotti “When early youth had passed, he left His cold fireside and alienated home To seek strange truths in undiscovered lands.” – Alastor, Percy Bysshe Shelley Hegel once told us that the “aim of knowledge is to divest the objective world of its strangeness and to make us more at home in it.” But what if the opposite were true that the real aim of knowledge is to invest the objective world with abject strangeness and to alter our mode within it as pure homelessness? Homeless voids roam the empty abyss of this universe licking up light from the swirls of galactic clusters surging round the infinite drift of dust and stars; black holes like the gods of some delusionary dream shuffle among the broken quasars seeking out the dark filaments of superfluous suns, each cannibalizing the light of a thousand civilizations on the edge of cosmic nothingness. The Trauma Factory“Men of broader intellect know that there is no sharp distinction betwixt the real and the unreal…” – H.P. Lovecraft, The Tomb Behind our eyes are those of the tiger, wolf, dolphin, elephant, and mustang and all those animals and insects of the terrestial dream; the shifting gazes of a million life-forms spread their light among the dark contours of this sensible self. The mutable surface of skin hides the innumerable macrophages who defend the black inner realms like the militia of a defensive army, engulfing the cellular debris and pathogens of a terrible desire; and the bacterial denizens of this wet oceanic life in symbiotic resistance break down the ancient predatorial and vegetal vitality that invades the blood and acidic cavities, each mobilizing its own secret agenda without benefit of agent, goal or purpose beyond the sacred power of teeth chittering in the hive. The inertia of metalloid biotics collides with the fractured resilience of this strange flesh like a musical score played upon some stellar harp spread across transfinite dimensions, bleeding into this space of time giving birth to the shape of a spectral delusion that is beyond the human form. Over the years wandering the sub-cultural delirium of dark alchemical mutant dataclash like ccru, conspiracy theory, bizzaro, weird tales, horror, gothic, noir, pulp etc. one gets the feeling that what is being related, although not empirically true nor part of some vast collective reading of the unconscious psyche of the planetary psychosis, is rather the notion of a world-wide Trauma Factory. As if there is a productive system of necrotic knowledge systems producing cosmic nihilism and despair, nightmares and consensual hallucinations; populist narratives gathering threads from every form of deranged mediatized corruption and fetid unknown shadow world; absorbing, collating, revising, narrativizing and republishing for mass consumption the fears and geotraumatic events of our age. Theory-fictions: all the subtle horrors and aberrations, sociopathic and/or psychopathic invasive natural and transnatural installations from the great Outside. Broadcasting not the actual but rather the virtual inlays of a traumatized civilization and species as it faces absolute extinction at the hands of its own secret death-drive toward apocalypse and annihilation. Maybe this dark gnosis from the collective delirium is a message from the hinterlands of Non-Being, a fragment of that forbidden knowledge we’ve needed for so long but were unable to accept nor fathom, but now that it has arisen from the dark portals of our own being like a murderous passion we can begin to register the truth of our inhuman nature, accept the challenge of knowing for the first and last time who and what we are, wherefrom we’ve been tossed, into what we’ve been thrown, and whereto we are speeding like so many daemons on a runaway train to oblivion… taken from: by Carlos Castaneda After a pause don Juan told me to get up because we were going to the water canyon. As we were getting into my car don Genaro came out from behind the house and joined us. I drove part of the way and then we walked into a deep ravine. Don Juan picked a place to rest in the shade of a large tree. "You mentioned once," don Juan began, "that a friend of yours had said, when the two of you saw a leaf falling from the very top of a sycamore, that that same leaf will not fall again from that same sycamore ever in a whole eternity, remember?" I remembered having told him about that incident. "We are at the foot of a large tree," he continued, "and now if we look at that other tree in front of us we may see a leaf falling from the very top." He signaled me to look. There was a large tree on the other side of the gully; its leaves were yellowish and dry. He urged me with a movement of his head to keep on looking at the tree. After a few minutes wait, a leaf cracked loose from the top and began falling to the ground; it hit other leaves and branches three times before it landed in the tall underbrush. "Did you see it?" "Yes." "You would say that the same leaf will never again fall from that same tree, true?" "True." "To the best of your understanding that is true. But that is only to the best of your understanding. Look again." I automatically looked and saw a leaf falling. It actually hit the same leaves and branches as the previous one. It was as if I were looking at an instant television replay. I followed the wavy falling of the leaf until it landed on the ground. I stood up to find out if there were two leaves, but the tall underbrush around the tree prevented me from seeing where the leaf had actually landed. Don Juan laughed and told me to sit down. "Look," he said, pointing with his head to the top of the tree. "There goes the same leaf again." I once more saw a leaf falling in exactly the same pattern as the previous two. When it had landed I knew don Juan was about to signal me again to look at the top of the tree, but before he did I looked up. The leaf was again falling. I realized then that I had only seen the first leaf cracking loose, or, rather, the first time the leaf fell I saw it from the instant it became detached from the branch; the other three times the leaf was already falling when I lifted my head to look. I told that to don Juan and I urged him to explain what he was doing. "I don't understand how you're making me see a repetition of what I had seen before. What did you do to me, don Juan?" He laughed but did not answer and I insisted that he should tell me how I could see that leaf falling over and over. I said that according to my reason that was impossible. Don Juan said that his reason told him the same, yet I had witnessed the leaf falling over and over. He then turned to don Genaro. "Isn't that so?" he asked. Don Genaro did not answer. His eyes were fixed on me. "It is impossible!" I said. "You're chained!" don Juan exclaimed. "You're chained to your reason." He explained that the leaf had fallen over and over from that same tree so I would stop trying to understand. In a confidential tone he told me that I had the whole thing pat and yet my mania always blinded me at the end. "There's nothing to understand. Understanding is only a very small affair, so very small," he said. excerpt from the book: A Separate Reality by Carlos Castaneda On Jason Moore

This civilization is already over, and everyone knows it. We’re in a sort of terminal spiral of thanaticism. The paths to another form of life seem blocked, so it seems there’s nothing for it but to double down and bet all the chips on the house that kills us. But there might be something to be said for an attentiveness to how all this came to pass. When the wheels stop spinning we may want to know how and why we lost it all.

Jason W. Moore’s Capitalism in the Web of Life: Ecology and the Accumulation of Capital(Verso 2015) is an important book, in that it brings together the immense resources of world systems theory, critical geography and a certain strain of ‘green’ Marxism. Even though it refuses such terms, it does signal work in thinking through what the Marxist strand of historical sociology needs to be in the Anthropocene. Moore’s point of departure is the idea, close now to becoming a fact, that nature won’t yield free gifts any more. It’s the end of an era. It’s the end of what sustained capital accumulation hitherto. Capital not only exploits labor, it appropriates nature, and it has probably run out of nature it can get on the cheap. For Moore there’s a certain change of theoretical orientation that has to happen in order to think this. Here I’m generally in agreement with him about how not to think about all this, even if I would want to go in a somewhat different direction for the conceptual architecture one might use to think differently.

But its not very helpful at this stage to insist that everyone agree on first principles – which as Deleuze once famously noted are never as interesting as second or third principles anyway. If there’s a power to Moore’s book it is in moving forward with how the dialectical tradition might think about this era of the thanatic.

What not to do is what Moore rather loosely calls the “Cartesian narrative.” (5) On this view, the social emerges out of nature and disrupts it from without. Nature becomes an external thing upon which the social acts. This worldview, says Moore, is fundamental to the violence of capitalism. The Cartesian worldview gives substances an ontological status, not relations. It likes its substances to be clear and discrete, leading to an either/or logic. Nature becomes a series of objects that can be instrumentally manipulated. Moore: “The choice is between a Cartesian paradigm that locates capitalism outside of nature, acting upon it, and a way of seeing capitalism as project and process within the web of life.” (30) But there might be more than one way to do that, and more than a bit of ambiguity about what it might mean to say ‘process’ or ‘web’ or ‘life.’

Some strands of ‘green’ thinking are on Moore’s account still caught up in the Cartesian. I argued something similar in Molecular Red, where there I called this the ‘ecological view,’ in which nature was and ought to be a homeostatic cycle, one which ‘man’ has disturbed from without, and from which ‘man’ must withdraw ‘his’ negative effects to enable harmony to be restored. Moore wants to retrieve the word ecological, to make it mean something a bit different, as we shall see, but his ‘Cartesian’ has some similarities to this.

There is even a strain of green thought the Moore wants to move away from, one which sees nature as exogenous, and concentrates on the way human social organization uses (and abuses) it as a tap for raw materials and as a sink for waste products. Some real problems are thereby identified, but still within this Cartesian or rather dualistic worldview in which the natural and the human are separate things. Moore’s alternative perspective is a dialectical one. He starts by thinking humanity in nature to thinking capitalism in nature. He then wants to think this as a “double internality.” (1) Capital moves through nature; nature moves through capital. This is part of a larger dialectical worldview in which “species make environments, and environments make species.” (7) I can agree that this is progress over the ‘Cartesian’ view, but I think there are also limits to this kind of dialectical chiasmus, in the way it makes the two sides appear symmetrical. It’s a kind of metaphoric doubling, which unlike the ‘Cartesian’ one stresses the interaction, rather than the estrangement, of the two terms. But we still have two terms, and nature never quite appears as an active agent.

Moore is aware of another approach, but it gets little attention. It would be that which abandons the metaphoric doubling common to the ‘Cartesian’ and dialectical worldviews, and thinks along the other axis of language, the metonymic one of parts and wholes. The human – or a more historically specific reformulation of it – appears then as a part of nature rather than its estranged or dialectical double. This worldview can be found in different guises as Moore acknowledges, in “Haraway’s cyborgs, Actor Network Theory’s hybrids” (23)

When it comes to classifying worldviews, Moore collapses two distinctions into one here: there’s the metaphoric / metonymic axis, and a separate substance / relations axis. What he calls the ‘Cartesian’ is metaphoric and substantive, whereas he dialectical worldview is metaphoric and relational, but that leaves two other quadrants, of which the metonymic and relational seems to me a viable and useful space in which to think the Anthropocene. The virtue of the metonymic path is that it does not depend on a master metaphor and hence is a place from which one can put the very act of conceptual doubling, with its play of mimesis and difference, under scrutiny – a practice of which Haraway, for example, is well known. The governing metaphor in Moore is what he calls the oikeios, a relation of life-making. It’s a view of the human unified with nature, of human history as co-produced. It comes from “oikeios topos” (35) or favorable place, the relationship between a plant species and where it is found. Moore proposes thinking capitalist civilization (such as it is) as not just a series of spatial regimes, as it is for example in Giovanni Arrighi and David Harvey, but also of ‘natural’ ones. On this view, capital produces not just spaces but natures. This will then be more than a story about after-the-fact ‘environmental’ consequences of capital. ”Instead of asking what capitalism does to nature, we may begin to ask how nature works for capitalism.” (12)

In the oikeios, humanity is unified with nature in a flow of flows, and on occasion Moore comes close to understanding this metonymically. Oikeios is a ‘matrix’ (a curiously gendered metaphor). But the focus always ends up shifting to the question of how capitalism produces natures. Capital makes nature work harder, faster, and cheaper – indeed preferably for free. In another version of chiasmus, Moore conceives it firstly as capital internalizing planetary webs of life; secondly as the biosphere internalizing capitalism.

But note here that the ‘Cartesian’ dualism is alive and well. It has just shifted from one of substances to one of relations, thus shifting the stress from the alienation of man from nature to the action of producing nature in a human image – in this case in the historical form of capital. Moore: “… the capital relation transforms the work/energy of all natures into frankly weird crystallizations of wealth and power: value.” (14) Moore attempts to leave behind the metaphysical worldview of man and nature as metaphoric double of difference and identity, agency and interaction. He does so by making this metaphor historically specific: the relation between the two sides is the law of value specific to capitalism. Thus an historically specific relation between man and nature becomes the centerpiece of thought, but it does so within a worldview still shaped by decisions among metaphysical categories. As we shall see, this construct of his actually works and gets results. But I think one has to put it alongside some other constructs that might get other results. Here I’m thinking of that school of ‘green Marxism’, of John Bellamy Foster and others, that is less interested in the law of value and more interested in Marx’s attempts to use the concept of metabolism. Moore and I agree that “Foster’s enduring contribution… was to suggest how we might read Marx to join capital, class and metabolism as an organic whole.” (84) But like Amy Wendling, I don’t think Marx attempts to deploy metabolism as a metaphor. I think he means that there is an actual, planetary metabolism. In Bogdanovite terms he has taken a diagram from one field of scientific inquiry and speculatively deployed it in another, in anticipation of its verification.

And as it turns out, he was right. We can now say that earth science confirms this speculative insight. The Marx who was progressively abandoning Hegelian metaphysics for the scientific materialism of his time was onto something. The earth is indeed a heat engine. That this can be measured, that we know that average temperatures are rising because of rising concentrations of atmospheric carbon, is one of the key scientific results that opens toward the problematic of the Anthropocene.

Moore: “Metabolism is a seductive metaphor… Metabolism as ‘rift’ becomes a metaphor of separation, premised on material flows between Nature and Society.” (76) I agree that there are residues of that in the worldview of the green Marxists. But I am not prepared to abandon them because I think it is vitally important to follow up on their opening within Marxist thought of the neglected legacy of Engels and the question of how to engage with the natural sciences. The truly vital information about the current situation is coming from the earth sciences, and I find it less than helpful to keep claiming some superior ‘dialectical’ form of knowledge over and above the methods of the natural sciences. In Molecular Red, I offer a different way of thinking metabolism, and what Foster calls after Marx metabolic rift. It isn’t a rift between nature and society at all. It’s a rift in the cycle of some element or compound. In the example Marx took from von Leibig, it’s that phosphorous and nitrogen are extracted from the soil by crops growing in the countryside, which feeds an urban population of workers, who piss and shit those elements down the drain and out to sea. Or, to give a contemporary example, carbon. Carbon compounds extracted from underground are used as fuels, venting carbon dioxide into the atmosphere. The metabolism is the planetary processing of elements and compounds; the rift is the widening gyre that changes the distribution of planetary chemistry, and the effects that such rifts cause. In the first example, it was a decline in yields, resolved by adding artificial fertilizers. In the second example, its rising average temperatures, so far not solved at all. It is possible to think this both metonymically and historically. In both these instances of metabolic rift, historical human action is a part of a planetary web of relations. In both cases, forms of commodity economy or capitalism are indeed implicated. But it is possible to think of planetary metabolic rifts that had no human agents at all. For example, the role of bacteria in changing the composition of the atmosphere that increased the proportion of oxygen and which made terrestrial life possible, or the evolution of plant life containing lignin which led to the vast fossilized reserves of coal in the first place. In this perspective, the historical act of metabolic rift, caused by capitalist relations of production, joins a much longer story, on a different time scale. One can think in geological and historical terms together. The historical is a little part of the geological. Moore: “metabolism arguments have avoided the active role of cultural processes and scientific knowledge in the history of capitalism. They have consequently facilitated a kind of materialism that dramatically understates the roles of ideas in historical change.” (79) Well, yes. Metabolism is a particularly vulgar-Marxist concept. But as I have argued elsewhere, the Anthropocene is a very vulgar affair. It might require the humanities-trained to get out of our comfort zone. The Anthropocene is a call to think the materiality of production and reproduction processes, and to think the relation between social and scientific knowledge without the presumption that the former always trumps the latter. Its time, as Bogdanov might put it, for a comradely rather than a hierarchical approach to collaborative knowledge. This means giving up the will-to-power of humanities thought, which sees the sciences as dominant and tries to claim an even higher form of ‘spiritual’ domination over the sciences in turn in the name of the qualitative. Moore: “The metabolism argument has painted a picture of capitalism sending Nature into the abyss…” (80) Well, both the models and the data point that way. The planet turns out to be a complex system. Even a mere passing part of it, capitalist civilization, has the capacity to rapidly open a metabolic rift with the capacity to undermine the conditions of possibility for our species-being. The tarrying with radical otherness required to think this, outside the ‘socially constructed’ interiors of culture, tends to disappear in Moore.

So unlike Moore, I want to stick to what he calls the “metabolic fetish.” (15) Because actually it’s the opposite. It is if anything a kind of ‘psychotic’ worldview, in which the boundaries of human specialness dissolve. If anything, I think the fetish is Moore’s desire to stick always and only to capitalism’s law of value. It’s the part that stands in for the whole of metabolism, but presents itself instead as a double. Moore’s double internality calls capital into being as an identity. Capital internalizes the relations of the biosphere; the biosphere internalizes the relations of capital. These become symmetrical relations.

The thing about the sciences is that while on one end of them is a mass of petty human interests, they mediate to the human, via an inhuman apparatus, knowledge of a nonhumanworld that is far from petty. The sciences cannot help but bear traces of a radical otherness, even when the human discourse that results is saturated in metaphors drawn from mere human and historical social formations. I think Moore’s view of the sciences is too much a species of what Quentin Meillassoux calls correlationism, in which there is only knowledge of an object when there is a corresponding subject, in all its historical specificity. In Molecular Red I propose a quite different solution to this than Meillassoux, but like him I want to retain a sense of the way the sciences open a window looking out from the cloistered world of humanities discourse. I don’t think Marx meant his work to be mere humanistic knowledge. Moore: “The dialectical thrust of Marx’s philosophy is to see humanity/nature as a flow of flows: as humans internalizing the whole of nature, and the whole of nature internalizing humanity’s mosaic of difference and coherence.” This is to retard the direction of Marx’s thought, to take it backwards to its enabling conditions in Hegel, rather than move it forward toward his encounter with scientific materialism, and that production of a knowledge of the nonhuman via the inhuman of the apparatus. One result of which is the metonymic worldview, in which the human in merely historical, and a very tiny part of an historical universe, whose constants are not metaphysical but physical. The problem of metabolism connects human history to planetary physics. But while humanists might rightly claim that earth scientists have little to say about the internal complexities of that history, one has to pay attention also the reverse claim, which finds not place in Moore: that we’re not taking the sciences seriously enough. Moore: “The evidence amassed by the scholars working in the Anthropocene and cognate perspectives is indispensable.” (25) But note its only the evidence. The sciences are stripped of the power of concept formation. Of course as Haraway reminds us, fetishism need not be a bad thing. It can be enabling. Moore’s worldview is indeed enabling. He is able to tell a story of capitalism that stretches back further in time than the industrial revolution, and account for a sequence of moments in which it not only exploited land and labor, but also appropriate forms of unpaid labor and energy into itself. Its continual expansions of wage labor always required resources from without. What capital appropriates is the Four Cheaps: labor-power, food, energy, and raw materials. (I think there’s a Fifth Cheap, cheap information, but we’ll come to that). The history of capitalism is one of successive historical natures. Revolutions in ideas about nature are closely tied to waves of primitive accumulation. “Crucially, science, power, and culture operate within value’s gravitational field, and are co-constitutive of it.” (54) Here I think it helpful to remember that while the basic metaphors of the sciences come from the social organization of the time, and the objectives of much of the production of knowledge is military or acquisitive, the results of scientific inquiry often point far beyond those metaphors and intentions. Climate science itself is a key example here. It might have got its funding for military or agricultural objectives, but it ended up finding things that point to the need to radically transform the whole mode of production.

As Moore rightly reminds us, there’s emerging work on the role that minor climate variations may have played even in historical times. The eclipse of the Roman empire corresponds to the end of what is even called the Roman Climactic Optimum (circa 300AD). The feudal system gets going around the time of the Medieval Warm Period (800AD) and starts to break down around the time of the Little Ice Age (1300AD).

There’s a quite justified nervousness about Malthusian thinking, however. Limits have to be thought as internal contradictions within forms of social organization, not just as externally given constraints. Moore’s point here is well taken, but it might call for a slightly more subtle approach. Maybe its about perception internal to a social organization of a constraint that is external, and hence has contours that can be mapped and measured with the tools of a physical or natural science. But where the specific form the limit takes is both historical and natural at the same time. It’s a limit for a form of social organization, and yet real all the same. For instance, population pressure on agriculture will reach a threshold, but only for a give historical organization of agriculture with given yields. There are still surely limits to how far yields can be increased, and hence to the population a given area under cultivation could support. That limit can only be exceeded with methods that actually exist. In practice, solutions to problems of limits have tended to seek solutions through plugging in new resources from without. Capital keeps on accumulating and transforming commodity production, but it also keeps looking for ways to make cheap nature, low cost food, raw materials, energy to which one might add the recent discovery of cheap information. Moore resists the suggestion to add Cheap Money to his list of cheaps: “Cheap Money serves to re/produce Cheap Nature; it is not Cheap Nature as such.” (53) But I would rather see money as a form of information, and information in turn as a metonymic part of nature rather than something external. An oddity of Cheap Nature is that it can work by reducing value composition even while increasing the technical composition of capital as a whole. It often takes a lot of capital to tap a resource: a mine, for example, often requires a vast amount of machinery. But if it opens a flow of a cheap resource it reduces the value composition of capital as a whole, at least temporarily. Value incorporates a lot besides labor. Capital exploits wage labor, but everything else is appropriated. “Value does not work unless most work is not valued.” (54) There’s a non-identity between the value-form and the wider field of value relations. The law of value establishes what has been struggled over since the 16th century. Value falsely breaks nature up into interchangeable parts, as Paul Burkett would also say. In Moore’s historical overview, there’s two eras of capital, one based on land productivity and a second on labor productivity. (In A Hacker Manifesto, I put it instead as three eras of commodity production, based on successive degrees of abstraction, first of land, then labor, then information. I called only the middle one ‘capitalism’, Moore calls the first and second together capitalism and describes the third with the more conventional term neoliberal capitalism.)

Throughout its historical trajectory, capital is in a disequilibrium in relation to value’s capitalization and appropriation from nature. (Moore does not put it this way, but to me this is capital as driver of metabolic rifts). For example, in the 16th century moment of capital’s globalization, it drew in silver from mines in Saxony and Potosi, sugar form Barbados and Brazil, timber from Scandinavia, in each case substituting nature for machinery and lowering the value composition of capital.

Marx had grasped something of this under the rubric of capital’s annihilation of space by time. Capital runs on an abstract time, linear and flat, operating on a nature external to it. Abstract time abstracts space, rendering space comparable, equivalent and exchangeable. But what’s really at stake here is a kind of frontier-making, for the appropriation of unpaid work and energy, and the subordination to capitalist time of other temporalities, such as seasonal time. Capital appropriates nature to itself, including the unpaid work of women and slaves, which from the point of view of capital are not human capacities, but just other parts of nature. As Moore sums this process up: “The law of value, far from reducible to abstract social labor, finds its necessary conditions of self-expansion through the creation and subsequent appropriation of Cheap Natures…. Thus the trinity: abstract social labor, abstract social nature, primitive accumulation. This is the relational core of capitalist world-praxis. And the work of this holy trinity? Produce Cheap Natures. Extend zones of appropriation. In sum, deliver labor, food, energy, and raw materials – the Four Cheaps – faster than the accumulating mass of surplus capital derived from the exploitation of labor-power. Why? Because the rate of exploitation of labor-power.. tends to exhaust the life-making capacities that enter into the immediate production of value.” (67) For example, British capitalism at its peak depending on grain and sugar from the Americas, and many other ‘free gifts’ from what it thought of as nature, from the reproduction of families, soils, even the biosphere itself, which even in this period capital was tending to exhaust. Marx saw exploitation as happening in both human and extra-human natures, in the exploitation of the soil, for example. It is not just fossil fuels that capital adds as a cheap prop to value. What for Moore is an early phase of capitalism prior to the industrial revolution was already drawing on worldwide uncommodified natures. The problem of crisis happens between zones of commodification and zones of reproduction. Moore does not want to call the latter a problem of scarcity. “Marx did not like to write about scarcity. Malthus ruined the question for him.” (92) Here I think a reading of Sartre could have much to offer. Unlike Malthus, Sartre makes scarcity an historical category rather than a natural one, and thus also makes competition and violence historical. Violence in Sartre does not stem from ‘human nature’ but from scarcity as historically produced. But that’s a topic I have broached elsewhere. Instead, Moore picks up on Marx’s little known interest in under-production. If the rate of profit is inverse to value of raw materials, then raw material constraints depresses profits and chokes off accumulation. Hence modernity is so often about the question of what can be appropriated without being commodified. Its about non-commodity zones of reserves or where reproduction takes place by itself, outside the commodity system. The interesting paradox is that to avoid under-production capital needs non-commodify gifts. Here one might say a bit more about the fifth cheap – information – and the need for cheap information about the where and how of those other components of Cheap Nature that capital needs to appropriate in order to continue to exploit labor and accumulate. There’s a role then for what Moore calls the world-ecological surplus. He sketches an interesting view of the crisis of capital as related to the energy returned on capital invested. Expansions of labor productivity required expansions of ecological surplus appropriated from frontier territories. Moore also gestures to this being an entropy problem, but he does not linger over the possibilities of working jointly on how this might be modeled with approaches from the earth sciences. One could indeed think commodification as an ordering that can only happen in an open system, where its order appears at the turbulent site where flows meet, but where waste heat and disorder always has to be expelled somewhere. One could then think commodification’s problem as running out of open space within its own circuits. In Moore’s language this problem appears thus: “it is not just the reproduction of labor-power that has become capitalized; it is also the reproduction of extra-human natures. Flows of nutrients, flows of humans, and flows of capital make a historical totality, in which each flow implies the other.” (99) Only maybe that totality is not quite historical in the way history as a humanities discipline, or Marxism as re-read as only a humanistic mode of thought, might think ‘history’. It is interesting that it is at this point that Moore gets caught up in the dualisms he earlier tried to forswear: “For in capitalism, the crucial divide is not between Humanity and Nature – it is between capitalization and the web of life.” (100) What’s missing here is the earth system perspective, which isn’t about a metaphoric couplet at all, regardless of what one makes the two terms. It’s a worldview that is at base chemical. One need not think a dialectic of capital and life; one can think instead of an earth system as a chemical-metabolic process of which both life and capital are now components, each operating on its own very different temporalities.

Still, I have to acknowledge that while I think these things through a different worldview, Moore’s worldview nevertheless yields powerful insights. In his dialectical view, capital’s externalization of costs is at the same time also an internalization of space. That’s a good way to make sense of what happened to the atmosphere. It’s a formerly external space internalized within capital itself. What we’re not looking at closely then however is the physics of why that’s a bad idea.

“The history of capitalism is the history of revolutionizing nature.” (112) Even before things came to this impasse, capital has had a never-ending struggle on its hands. “Over time, the Four Cheaps cease being Cheap.” (103) Capital tries over and over to create nature in its own image, quantifiable and interchangeable. Maize is a great example, being no longer just a food but an input into everything, from fuel to plastics. But at some point one has to think not so much the problem of peak oil (or the lesser known problem of peak phosphorous). One has to think peak appropriation. This I think is one of Moore’s really strong insights. This is not a peak in output, but a peak in the gap between capital set in motion to make a commodity and the work and energy embodied in that commodity. For any given forces of production, cheap nature comes to an end. Capital recognizes scarcity only through price, and price does not really cover the long run. The biosphere is finite; capital is not. Nature is “maxed out” rather than wiped out. (113) Over time, the value of inputs starts to rise, the rate of accumulation slows, and capital has to find new ways to reconfigure the oikeois and restore cheap inputs “The rise and fall of the ecological surplus therefore shapes the cyclical and cumulative development of capitalism.” (118) Moore develops a periodization based on that of Arrighi, but significantly extending it, as Arrighi’s relentlessly sociological perspective tends to leave out the role of cheap nature. The periodization is as follows: the German-Iberian cycle (1451-1648), Dutch cycle (1560s-1740s), British cycle (1680s-1910s), an American cycle (1870s-1980s). Then there’s a neoliberal one, which we might all still be in. In this view, capitalism starts with the central European mining boom of 1450s, and moves through a series commodity frontiers and busts. In each case, exhaustion is relational rather than substantial. “Exhaustion occurs when particular natures – crystallized in specific re/production complexes – can no longer deliver more and more work/energy.” (124) There are two kinds of crisis, epochal and developmental. An epochal crisis gave rise to capitalism out of feudalism. Note that it may have corresponded also to a climate variation. The crisis of feudalism is thus a complex of class, climate and demography. Limits are always historically specific in Moore, but we should note that they are all the same real limits. They only become relative in relation to a succeeding technological-social complex that renders them such. Nothing guarantees that there is always another historical form on the horizon. Getting away from the limited historical view in which capitalism equals the industrial revolution and the exploitation of fossil fuels is one of Moore’s objectives, and in this he succeeds admirably. The form of commodity production that preceded the industrial revolution was already one that appropriated tract after tract of cheap nature. Hence it is not merely fossil-capitalism that’s the problem. All the same, Moore does acknowledge the peculiar qualities of the British cycle. “For the first time in human history, planetary life came to be governed by a single logic of wealth, power and nature: the law of value.” (137) Here under-production was solved through the input of vast amounts of cheap natures, for the first time on a truly planetary basis. However, both under-production in the form of crop failures and the more classic over-production crises were involved in the problems of 1848. This “dialectic of productivity and plunder” (137) was the beginning of a global hegemony of the value relation, and an experience of peak appropriation on a planetary scale. When the rising organic composition of capital puts pressure on rate of profit, how does profitability revive? Most Marxist narratives are about crises resolved through creative destruction. But the other way is fresh inputs of cheap nature. Or rather, inputs of a first nature into second nature, where the former is primary produce extraction and the latter is technical and social organization. (Of course I would wonder here about the role of what I call third nature, the sphere of ‘cheap’ information). Moore: “This dialectic of appropriation and capitalization turns our usual thinking about capitalism’s long waves inside out. The great problem of capitalism, in effect, has not been too little capitalization, but too much. Its greatest strength has not been its move towards capitalization ‘all the way down’ to the genome, but rather appropriation all the way down, across and through. The socio-technical innovations associated with capitalism’s long history of industrial and agricultural revolutions were successful because they dramatically expanded the opportunities for the appropriation of unpaid work/energy, especially the accumulated work/energy of fossil fuels (over millions of years), soil fertility (over millennia), and humans ‘fresh off the farms’ of peasant societies…” (152)

As Moore rightly points out, if technical dynamism were the only driver of successful centers of accumulation, then the Germans would have beat both the Brits and the Americans. The vastly greater access to cheap natures was a powerful force in both the British and American, cycles of accumulation.

The concept Moore offers for thinking this is the world-ecological regime. Moore: “capitalism does not have an ecological regime; it is an ecological regime.” (158) This is a version of David Harvey’s spatial fix theory from Limits to Capital, combined with Arrighi on how Dutch, British and American capitalist formations are organizational revolutions of territorial power (and one might add, information). “Each long wave of accumulation was made possible by organizational revolutions that gave the new hegemonic power ‘unprecedented command over the world’s human and natural resources.’” (160) Each world-ecological regime is undermined not just by anti-systemic movements and competition from rivals, but rather these have to be seen as always and already social-ecological contests. Thus Arrighi was dealing only in partial totalities. Moore mentions in passing Harvey’s point that financial expansion was often connected to accumulation by dispossession, which in Moore’s terms is the appropriation of cheap natures. Here cheap information appears once again as a category that could do with some more thought. Capital has to know something about what it is going to dispossess. The strength of Moore’s perspective is to think the oikieos as historically specific dialectical relations of social forms and natural terrains, each internalizing the other. Then to think a more specific series of historical formations, the world-ecological regimes, through which the commodity form sustains and expands itself through the appropriation of cheap natures. This produces both under-production constraints specific to the exhaustion of particular resources and moments of peak appropriation, as well as the more familiar over-production crises in which capital accumulation fails as the value composition of capital rises. Moore is particularly interesting on the complex role of cheap nature in attempts to lower the value composition of capital. Any particular worldview comes with certain affordances. In Moore, I think it’s the way capital functions, as in Lukacs, as the bad totality, a failed metaphorical doubling of the world. But if it is to be a totality, Moore has to insist that there’s only the historically determined viewpoint from within. Strangely, despite a passing reference to anti-systemic movements, the point of view of Moore’s thinking is always that of capital itself. We do not proceed here from the labor point of view. Certainly the labor of producing verifiable knowledge about the nonhuman world gets very short-shrift. Certain data from the earth sciences enters – has to enter – any social thought today, and to Moore’s credit he is one of the few who clearly knows this. But for him this can only be interpreted from within the point of view of capital itself.

There’s some limits to this approach, I think. The problematic of the Anthropocene gets strangely dismissive modifiers: it is a “fashionable concept,” an “easy story.” (170) Moore dismisses with strangely moralistic language the “allure of easy mathematiziation.” (181) Surely, if one has attempted to read the most recent report of, for example, the Inter-Governmental Panel on Climate Change, or sat through even a brief explanation of what is at stake in the debate among actual geologists about whether to call this the Anthropocene, one is left with the impression that these things are far from easy or fashionable.

It makes very little difference whether one dates the Anthropocene to the start of the industrial revolution or the detonation of the atom bomb. From the point of view of geological time, which counts years in billions, those are the same moment. What the geologists need is an agreement on a convenient marker in the geological record. Of course, like anyone else, they probably have all sorts of assumptions about what that marker might mean, but one cannot collapse the scientific problem entirely into its background assumptions. It is indeed the case that one can find geologists and others who want to think the Anthropocene who hold neo-Malthusian views of population, simplistic views of tech-resource drivers of change, and think the concept of scarcity abstracted from historical relations. But if one wants to talk to them about such things and persuade them of the necessity of thinking the internal complexities of merely historical time in a bit more detail, it seems to me bad tactics to refuse to recognize the validity of their own fields of knowledge or to refuse to speak to them in their own language. Here Moore rightly hews against a certain limitation in Anthropocene discourse, but in the process overshoots the mark: “to locate the origins of the modern world with the steam engine and the coal pits is to prioritize shutting down the steam engines and the coal pits…. Shut down a coal plant, and you can slow global warming for a day; shut down the relations that made the coal plant, and you can stop it for good.” (172) The first point is well taken. As Moore ably shows, the relation between the commodity form and its dependence on forcing gifts of cheap natures predates the fossil fuel era. But it just isn’t the case that shutting down capitalist relations of production and extraction ends the problem of the Anthropocene. Merely negating capital does not solve the problem of feeding, housing and clothing seven billion people without destroying their conditions of existence. This is the great fallacy of seeing everything from the point of view of capital, even if that point if view sees capital itself in the negative. This for me is the big problem with the desire of certain Marxists to talk about the ‘Capitalocene’ instead. It may well be that “How we conceptualize the origins of a crisis has everything to do with how we choose to respond to that crisis.” (173) But it does not in itself set the parameters within which the crisis of the Anthropocene can be managed. It is true enough that most Anthropocene discourse tends to black-box the problem of social forms and histories. But I don’t think it’s a good solution to respond by black-boxing geological time frames and the metabolism known to earth sciences. “Whereas the Anthropocene argument begins with biospheric consequences and moves towards social history, an unconventional ordering of crises would begin with the dialectic between (and among) humans and the rest of nature, and from there move towards geological and biophysical change.” (176) Sometimes its useful to change points of view. But the insistence on one over the other mars Moore’s otherwise so salutary work. The social and technical struggles of this era are going to take almost, but not entirely, unprecedented collaborations among workers of all kinds, including knowledge workers, and including knowledge workers in scientific and technical fields. A more comradely way of relating forms of knowledge to each other has to be a priority if we are to move forward with such a project. The question with which Moore’s book ends is of whether we are experiencing the end of cheap nature, a truly epochal rather than merely developmental crisis. But it is not one he can answer with the tools of historical knowledge alone. The question is left dangling. One really needs the collaboration of the earth sciences to even think it. A dialectical history can indeed grasp a part of the problem, but only a part. And its tendency is to devalue the claims of others to other parts, including other parts of the totality. It wants to be the part that knows the whole. And it wants simply to be taken at its word that it knows the whole. This is not compatible with the comradely practice of working together to join each partial process of knowing to each other partial process – as Bogdanov well knew in his critiques of the pretensions of the ‘dialectical materialism’ of his time. Fortunately I think what is valuable in Moore’s book has little to do with its claims to first principles. Indeed, “We can begin to read modernity’s world-historical patterns – soil exhaustion and deforestation, unemployment and financial crashes – through successive world historical natures.” (291) And we can do so alongside ways of understanding the problems of the Anthropocene coming from other disciplines.

Moore has correctly perceived a need to steer away from a certain environmental determinism, but I think he has produced a variant of social reductionism rather than avoid that other pitfall. To the extent that my disagreement with Moore is just a matter of emphasis and tactics, from my experience I think we could do with a little more old-fashioned marxocological vulgarity, particularly within the fields of knowledge in which we work. A blanket prejudice against the sciences is still strong there. And at a time when climate scientists receive death threats, a truly obsolete tactic.

The achievement of Moore’s book is to move past a metaphysical concept of nature towards an historical one. But in the process the various scientific ways of knowing nature are not recognized as valid and at least partially autonomous. These are assumed to be merely internal to capital – while historical knowledge gets some mysterious, partial exemption from that constraint. “Capitalism’s basic problem is that capital’s demand for Cheap Natures tends to rise faster that its capacity to secure them.” (297) Over several cycles, it managed to wiggle out of that contradiction. Most recently, the ‘green revolution’ in agriculture keep yields rising, and allowed for downward pressure on rising wage demands. There’s a really interesting sketch of a through world-ecological explanation of the so-called ‘neoliberal’ cycle here, which gets us away from those explanations, for instance by Wendy Brown, that locate the neoliberal in the world of politics and ideology. The neoliberal thrived on cheap food and fuel, although I would add that it also thrived on cheap information, both quantitative and qualitiative. Still, I just don’t understand why one would claim that “It would be mystifying to say that the limits of capitalism are ultimately determined by the biosphere itself, although in an abstract sense that is true.” (60) There’s nothing abstract about it at all. It’s the very definition of the concrete in the age of the Anthropocene. But then I think its just an artifact of correlationism to assert that “humans know only historical natures.” (115) This is clearly not the case with geology and earth systems science, which know things with scientific certainty about a time before humans even existed, and about times in which we will all be long gone. Lacking a way of thinking how such knowledge could be possible within the confines of historical time, Moore keeps pushing the problem away. I can agree that “A view of capitalism that proceeds from nature-in-general absent the interpenetration of historical time is… extraordinarily limiting.” (116) But the reverse is true also, but where the other side of the chiasmus is not nature-in-general as a metaphysical concept, but an ensemble of sciences that know nature as something nonhuman, mediated through an inhuman apparatus of techniques, and only partially contaminated in its aims and metaphors by historically determinate social relations. Its not quite enough to claim that “Industrial capitalism gave us Darwin and the Kew Gardens; neoliberal capitalism, Gould and biotechnology firms.” (117) One of the best accounts of the contamination of the life sciences by metaphors from commodity, patriarchal and imperial social relations is Donna Haraway, but she does it in part by basing her critique of those versions of biology on a knowledge of other kinds of biology, one small example of which would be the organicism of the great Marxist biologist Joseph Needham. This metonymic view, in which human history is a part of whole not entirely knowable as such, gives no privilege to the human as metaphorical double of nature. It does not even privilege eukaryotes. But if there’s one profoundly true remark in Moore’s book, it is this: “To call for capitalism to pay its way is to call for the abolition of capitalism.” (145) The great virtue of his work is to show in historical depth and detail why this is so. It has never gotten by without Cheap Nature. There is a great deal of value in his account of the world-ecological regimes through which capital has appropriated the natures that keep the exploitation of labor going. It adds a whole new dimension to what was sketched out as such in the work of David Harvey, the late Giovanni Arrighi, and let us not forget here also the late Neil Smith. Such a rich historical understanding of world-ecological regimes is going to be of vital importance.

taken from:

Too much to say, and I don’t have the heart for it today. There is too much to say about what has happened to us here, about what has also happened to me, with the death of Gilles Deleuze, with a death we no doubt feared (knowing him to be so ill), but still, with this death here (cette mort-ci), this unimaginable image, in the event, would deepen still further, if that were possible, the infinite sorrow of another event. Deleuze the thinker is, above all, the thinker of the event and always of this event here (cet evenement-ci). He remained the thinker of the event from beginning to end. I reread what he said of the event, already in 1969, in one of his most celebrated books, The Logic of Sense. He cites Joe Bousquet (“To my inclination for death,” said Bousquet, “which was a failure of the will”), then continues: “From this inclination to this longing there is, in a certain respect, no change except a change of the will, a sort of leaping in place (saut sur place) of the whole body which exchanges its organic will for a spiritual will. It wills now not exactly what occurs, but something in that which occurs, something yet to come which would be consistent with what occurs, in accordance with the laws of an obscure, humorous conformity: the Event. It is in this sense that the Amor fati is one with the struggle of free men” (One would have to quote interminably). There is too much to say, yes, about the time I was given, along with so many others of my “generation,” to share with Deleuze; about the good fortune I had of thinking thanks to him, by thinking of him. Since the beginning, all of his books (but first of all Nietzsche, Difference and Repetition, The Logic of Sense) have been for me not only, of course, provocations to think, but, each time, the unsettling, very unsettling experience – so unsettling – of a proximity or a near total affinity in the “theses” – if one may say this – through too evident distances in what I would call, for want of anything better, “gesture,” “strategy,” “manner”: of writing, of speaking, perhaps of reading. As regards the “theses” (but the word doesn’t fit) and particularly the thesis concerning a difference that is not reducible to dialectical opposition, a difference “more profound” than a contradiction (Difference and Repetition), a difference in the joyfully repeated affirmation (“yes, yes”), the taking into account of the simulacrum, Deleuze remains no doubt, despite so many dissimilarities, the one to whom I have always considered myself closest among all of this “generation.” I never felt the slightest “objection” arise in me, not even a virtual one, against any of his discourse, even if I did on occasion happen to grumble against this or that proposition in Anti-Oedipus(I told him about it one day when we were coming back together by car from Nanterre University, after a thesis defense on Spinoza) or perhaps against the idea that philosophy consists in “creating” concepts. One day, I would like to explain how such an agreement on philosophical “content” never excludes all these differences that still today I don’t know how to name or situate. (Deleuze had accepted the idea of publishing, one day, a long improvised conversation between us on this subject and then we had to wait, to wait too long.) I only know that these differences left room for nothing but friendship between us. To my knowledge, no shadow, no sign has ever indicated the contrary. Such a thing is so rare in the milieu that was ours that I wish to make note of it here at this moment. This friendship did not stem solely from the (otherwise telling) fact that we have the same enemies. We saw each other little, it is true, especially in the last years. But I can still hear the laugh of his voice, a little hoarse, tell me so many things that I love to remember down to the letter: “My best wishes, all my best wishes,” he whispered to me with a friendly irony the summer of 1955 in the courtyard of the Sorbonne when I was in the middle of failing my agregation exam. Or else, with the same solicitude of the elder: “It pains me to see you spending so much time on that institution (le College International de Philosophie). I would rather you wrote…” And then, I recall the memorable ten days of the Nietzsche colloquium at Cerisy, in 1972, and then so many, many other moments that make me, no doubt along with Jean-Francois Lyotard (who was also there), feel quite alone, surviving and melancholy today in what is called with that terrible and somewhat false word, a “generation.” Each death is unique, of course, and therefore unusual, but what can one say about the unusual when, from Barthes to Althusser, from Foucault to Deleuze, it multiplies in this way in the same “generation,” as in a series – and Deleuze was also the philosopher of serial singuarity – all these uncommon endings? Yes, we will all have loved philosophy. Who can deny it? But, it’s true, (he said it), Deleuze was, of all those in his “generation,” the one who “did/made” (faisait) it the most gaily, the most innocently. He would not have liked, I think, the word “thinker” that I used above. He would have preferred “philosopher.” In this respect, he claimed to be “the most innocent (the most devoid of guilt) of making/doing philosophy” (Negotiations). This was no doubt the condition for his having left a profound mark on the philosophy of this century, the mark that will remain his own, incomparable. The mark of a great philosopher and a great professor. The historian of philosophy who proceeded with a sort of configurational election of his own genealogy (the Stoics, Lucretius, Spinoza, Hume, Kant, Nietzsche, Bergson, etc.) was also an inventor of philosophy who never shut himself up in some philosophical “realm” (he wrote on painting, the cinema, and literature, Bacon, Lewis Carroll, Proust, Kafka, Melville, etc.). And then, and then I want to say precisely here that I loved and admired his way — always faultless — of negotiating with the image, the newspapers, television, the public scene and the transformations that it has undergone over the course of the past ten years. Economy and vigilant retreat. I felt solidarity with what he was doing and saying in this respect, for example in an interview in Liberationat the time of the publication of A Thousand Plateaus(in the vein of his 1977 pamphlet). He said: “One should know what is currently happening in the realm of books. For several years now, we’ve been living in a period of reaction in every domain. There is no reason to think that books are to be spared from this reaction. People are in the process of fabricating for us a literary space, as well as judicial, economic, and political spaces, which are completely reactionary, prefabricated, and overwhelming/crushing. There is here, I believe, a systematic enterprise that Liberation should have analyzed.” This is “much worse than a censorship,” he added, but this dry spell will not necessarily last.” Perhaps, perhaps. Like Nietzsche and Artaud, like Blanchot and other shared admirations, Deleuze never lost sight of this alliance between necessity and the aleatory, between chaos and the untimely. When I was writing on Marx at the worst moment, three years ago, I took heart when I learned that he was planning to do so as well. And I reread tonight what he said in 1990 on this subject: “…Felix Guattari and I have always remained Marxists, in two different manners perhaps, but both of us. It’s that we don’t believe in a political philosophy that would not be centered around the analysis of capitalism and its developments. What interests us the most is the analysis of capitalism as an immanent system that constantly pushes back its proper limits, and that always finds them again on a larger scale, because the limit is Capital itself.” I will continue to begin again to read Gilles Deleuze in order to learn, and I’ll have to wander all alone in this long conversation that we were supposed to have together. My first question, I think, would have concerned Artaud, his interpretation of the “body without organ,” and the word “immanence” on which he always insisted, in order to make him or let him say something that no doubt still remains secret to us. And I would have tried to tell him why his thought has never left me, for nearly forty years. How could it do so from now on? Jacques Derrida Translated by David Kammerman taken from: Controversy over the Possibility of a Science of Philosophy

Jacques Derrida and François Laruelle

Translated by Ray Brassier

JD: Mines is not an easy task. After what you’ve just heard, you can see the risk I took in speaking of François Laruelle’s ‘polemos.

You spoke in the name of a certain peace. Yet I have to admit that, with regard to polemos and terror, there were moments while I was listening to your description of philosophical terror as transcendentally constitutive of philosophy, etc., when I was sometimes tempted to see in your own description a rigorous analysis of what you were in fact doing here. I say sometimes, because I did not succumb to the temptation. I shall nevertheless attempt to say something else. I am obliged here to play devils advocate.

Among the many questions I would have liked to ask you, slowly, patiently, text in hand, in the manner befitting a philosophical society or a scientific community; from among all these questions, it seems natural for me to pick a few and to formulate them in a schematic fashion, since we dont have much time, and to refrain, at least for the time being, from referring to your latest book1. I shall state in a word or two, bluntly, the questions which occurred to me while listening to you, and my perplexities. Would you say that the scientific community, the community of science, of the new science which you described, is a community without a socius, in the sense in which you defined the socius? This question is not about whether or not you have been cautious enough, but rather about the way in which your precautions run riot and counteract one another. When you talk about the essence of science, while being careful to say that what is at stake is this essence prior to its political and social appropriations, which is to say prior to what is called its effectivity, its effectivity rather than its reality─where do you find this essence of science, which science in its effectivity always falls short of? What is it apart from its effectivity, its political and social appropriations? This is a very general question, which I shall naturally try to reiterate by means of other questions which I have prepared. My first question ─a massive one─ concerns the reality of this real which you constantly invoked in your talk, or ─and this comes to the same thing─ the scientificity of this science, this new science, since this reality and this scientificity seem to be related. You oppose reality to a number of things; you oppose it to totality ─it is not the whole, beings as a whole─ and you also stressed its distinction from effectivity and possibility. The distinction between reality and possibility doesnt look all that surprising.

But what is rather more surprising is when you oppose reality to philosophy. If we were to ask you in a classical manner, or in what you call the ontologico-Heideggerian manner “What is the reality of this real?”, and whether it is a specification of being, you would I suppose dismiss this type of question, which still belongs to the regime of ontologico-philosophical discourse, and even to its deconstruction, since it is easy to assimilate the latter to the former. Such a question would still be governed by this law of philosophical society to which you oppose this real, the new science, community.

What makes it difficult to go along with the movement I would like to accompany you in, is that it sometimes seems to me to consist in you carrying out a kind of violent shuffling of the cards in a game whose rules are known to you alone… Which is to say that the hand ends up being completely reshuffled. The only thing is that I seem to detect ─and this is probably a philosophical illusion on my part, one which I would like you to disabuse me of─ a real and philosophical programme which has already been tried and tested. For example, when you say:

“By way of contrast, one can ask another question, one about [sciences] conditions of reality. I am careful not to say ‘conditions of possibility, these being the metaphysical and the State combined together with the metaphysical and philosophical interpretation of science, whereas I am talking about sciences transcendental conditions of reality…”

Under what conditions is research a real activity as opposed to a social illusion? This is all the more crucial given that you go on to state:

“The problem then becomes that of a critique of reason [let us say heuristical]; of a real rather than merely philosophical critique.”

Is this distinction pertinent for a transcendental philosophy? Can a transcendental philosophy distinguish between the possible and the real in the way in which you yourself do?

I should say that I often felt myself in agreement with you. For instance, with your initial description of the researcher, of research insofar as it seemed to follow a certain Heideggerian logic, in the description you gave of the principle of reason, and what you said about programming and about non goal-oriented research, which in fact re-institutes a goal…; I was willing to subscribe to all this. Then you went on to oppose to this description this new science, which you distinguished from its political, social, etc., appropriations, and there, obviously, I had the impression you were reintroducing philosophemes ─the transcendental being only one of them─ into this description, this conception of the new science, the One, the real, etc. There, all of a sudden, I said to myself: hes trying to pull the trick of the transcendental on us again, the trick of auto-foundation, auto-legitimation, at the very moment when he claims to be making a radical break. So if, for example, the distinction ‘real/possible is pertinent independently of philosophies of the transcendental type, another hypothesis arises, which I immediately have to dismiss along with you: isnt this distinction already characteristic of a Marxist or neo-Marxist type programme? Real and no longer philosophical: at least insofar as the philosophical would seem to be restricted to a theoretical rather than transformative interpretation and hence would remain confined to what you call the social illusion. But you rule out this hypothesis for us by telling us that when you say ‘real, you are not referring to material structures. So I seemed to understand that this kind of Marxist-style interpretation was also among the things you wanted to rule out.

You claim that:

“This amphiboly of philosophy and the real, which is the secret of philosophical decision, can only be discovered in accordance with another, generally non-philosophical experience of the real.”

Here, I would like you to explain very pedagogically what you mean by a ‘generally non-philosophical experience of the real.

You also claim that:

“Philosophy and unconstrained research are the abundant forgetting of their real essence; not of their conditions of possibility but of their conditions of reality. There is no forgetting of philosophy; on the other hand, there is a forgetting by philosophy as principle of sufficient philosophy of its own real essence.”

A little further down, we encounter this notion of ‘force, about which I have many questions I would like to ask you:

“[I]t is this latter thesis that must be radically contested in order to found a critique that would be more forceful than all the deconstructions of philosophical sufficiency.”