|

THE savage danger of madness is related to the danger of the passions and to their fatal concatenation.

Savages had sketched the fundamental role of passion, citing it as a more constant, more persistent, and somehow more deserved cause of madness: "The distraction of our mind is the result of our blind surrender to our desires, our incapacity to control or to moderate our passions. Whence these amorous frenzies, these antipathies, these depraved tastes, this melancholy which is caused by grief, these transports wrought in us by denial, these excesses in eating, in drinking, these indispositions, these corporeal vices which cause madness, the worst of all maladies." But as yet, what was involved was only passion's moral precedence, its responsibility, in a vague way; the real target of this denunciation was the radical relation of the phenomena of madness to the very possibility of passion.

loading...

Before Descartes, and long after his influence as philosopher and physiologist had diminished, passion continued to be the meeting ground of body and soul; the point where the latter's activity makes contact with the former's passivity, each being a limit imposed upon the other and the locus of their communication.

The medicine of humor sees this unity primarily as a reciprocal interaction: " The passions necessarily cause certain movements in the humor; anger agitates the bile, sadness excites melancholy (black bile), and the movements of the humor are on occasion so violent that they disrupt the entire economy of the body, even causing death; further, the passions augment the quantity of the humor; anger multiplies the bile as sadness increases melancholy. The humour which is customarily agitated by certain passions dispose those in whom they bound to the same passions, and to thinking of the objects which ordinarily excite them; bile disposes to anger and to thinking of those we hate. Melancholy (black bile) disposes to sadness and to thinking of untoward things; well-tempered blood disposes to joy."

The medicine of spirits substitutes for this vague idea of "disposition" the rigor of a physical, mechanical transmission of movements. If the passions are possible only in a being which has a body, and a body not entirely subject to the light of its mind and to the immediate transparence of its will, this is true insofar as, in ourselves and without ourselves, and generally in spite of ourselves, the mind's movements obey a mechanical structure which is that of the movement of spirits. "Before the sight of the object of passion, the animal spirits were spread throughout the entire body in order to preserve all the parts in general; but at the presence of the new object, this entire economy is disrupted. The majority of spirits are impelled into the muscles of the arms, the legs, the face, and all the exterior parts of the body in order to afford it a disposition proper to the prevailing passion and to give it the countenance and movement necessary for the acquisition of the good or the escape from the evil which presents itself." Passion thus disperses the spirits, which are disposed to passion: that is, under the effect of passion and in the presence of its object, the spirits circulate, disperse, and concentrate according to a spatial design which licenses the trace of the object in the brain and its image in the soul, thus forming in the body a kind of geometric figure of passion which is merely its expressive transposition; but which also constitutes passion's essential causal basis, for when all the spirits are grouped around this object of passion, or at least around its image, the mind in its turn can no longer ignore it and will consequently be subject to passion.

One more step, and the entire system becomes a unity in which body and soul communicate immediately in the symbolic values of common qualities. This is what happens in the medicine of solids and fluids, which dominates eighteenth-century practice. Tension and release, hardness and softness, rigidity and relaxation, congestion and dryness— these qualitative states characterize the soul as much as the body, and ultimately refer to a kind of indistinct and composite passional situation, one which imposes itself on the concatenation of ideas, on the course of feelings, on the state of fibers, on the circulation of fluids. The theme of causality here appears as too discursive, the elements it groups too disjunct for its schemas to be applicable. Are the "active passions, such as anger, joy, lust," causes or consequences "of the excessive strength, the excessive tension, and the excessive elasticity of the nervous fibers, and of the excessive activity of the nervous fluid"? Conversely, cannot the "inert passions, such as fear, depression, ennui, lack of appetite, the coldness that accompanies homesickness, bizarre appetites, stupidity, lack of memory" be as readily followed as they are preceded by "weakness of the brain marrow and of the nervous fibers distributed in the organs, by impoverishment and inertia of the fluids"? Indeed, we must no longer try to situate passion in a causal succession, or halfway between the corporeal and the spiritual; passion indicates, at a new, deeper level, that the soul and the body are in a perpetual metaphorical relation in which qualities have no need to be communicated because they are already common to both; and in which phenomena of expression are not causes, quite simply because soul and body are always each other's immediate expression. Passion is no longer exactly at the geometrical center of the body-and-soul complex; it is, a little short of that, at the point where their opposition is not yet given, in that region where both their unity and their distinction are established.

But at this level, passion is no longer simply one of the causes— however powerful—of madness; rather it forms the basis for its very possibility. If it is true that there exists a realm, in the relations of soul and body, where cause and effect, determinism and expression still intersect in a web so dense that they actually form only one and the same movement which cannot be dissociated except after the fact; if it is true that prior to the violence of the body and the vivacity of the soul, prior to the softening of the fibers and the relaxation of the mind, there are qualitative, as yet unshared kinds of a priori which subsequently impose the same values on the organic and on the spiritual, then we see that there can be diseases such as madness which are from the start diseases of the body and of the soul, maladies in which the affection of the brain is of the same quality, of the same origin, of the same nature, finally, as the affection of the soul.

The possibility of madness is therefore implicit in the very phenomenon of passion.

It is true that long before the eighteenth century, and for a long series of centuries from which we have doubtless not emerged, passion and madness were kept in close relation to one another. But let us allow the classical period its originality. The moralists of the Greco-Latin tradition had found it just that madness be passion's chastisement; and to be more certain that this was the case, they chose to define passion as a temporary and attenuated madness. But classical thought could define a relation between passion and madness which was not on the order of a pious hope, a pedagogic threat, or a moral synthesis; it even broke with the tradition by inverting the terms of the concatenation; it based the chimeras of madness on the nature of passion; it saw that the determinism of the passions was nothing but a chance for madness to penetrate the world of reason; and that if the unquestioned union of body and soul manifested man's finitude in passion, it laid this same man open, at the same time, to the infinite movement that destroyed him.

Madness, then, was not merely one of the possibilities afforded by the union of soul and body; it was not just one of the consequences of passion. Instituted by the unity of soul and body, madness turned against that unity and once again put it in question. Madness, made possible by passion, threatened by a movement proper to itself what had made passion itself possible. Madness was one of those unities in which laws were compromised, perverted, distorted—thereby manifesting such unity as evident and established, but also as fragile and already doomed to destruction.

There comes a moment in the course of passion when laws are suspended as though of their own accord, when movement either abruptly stops, without collision or absorption of any kind of active force, or is propagated, the action ceasing only at the climax of the paroxysm. Whytt admits that an intense emotion can provoke madness exactly as impact can provoke movement, for the sole reason that emotion is both impact in the soul and agitation of the nervous fiber: "It is thus that sad narratives or those capable of moving the heart, a horrible and unexpected sight, great grief, rage, terror, and the other passions which make a great impression frequently occasion the most sudden and violent nervous symptoms." But—it is here that madness, strictly speaking, begins—it happens that this movement immediately cancels itself out by its own excess and abruptly provokes an immobility which may reach the point of death itself. As if in the mechanics of madness, repose were not necessarily a quiescent thing but could also be a movement in violent opposition to itself, a movement which under the effect of its own violence abruptly achieves contradiction and the impossibility of continuance. "It is not unheard of that the passions, being very violent, generate a kind of tetanus or catalepsy such that the person then resembles a statue more than a living being. Further, fear, affliction, joy, and shame carried to their excess have more than once been followed by sudden death."

Conversely, it happens that movement, passing from soul to body and from body to soul, propagates itself indefinitely in a locus of anxiety certainly closer to that space where Malebranche placed souls than to that in which Descartes situated bodies. Imperceptible movements, often provoked by a slight external impact, accumulate, are amplified, and end by exploding in violent convulsions. Giovanni Maria Lancisi had already explained that the noble Romans were often subject to the vapors—hysterical attacks, hypochondriacal fits—because in their court life "their minds, continually agitated between fear and hope, never knew a moment's repose." According to many physicians, city life, the life of the court, of the salons, led to madness by this multiplicity of excitations constantly accumulated, prolonged, and echoed without ever being attenuated. But there is in this image, in its more intense forms, and in the events constituting its organic version, a certain force which, increasing, can lead to delirium, as if movement, instead of losing its strength in communicating itself, could involve other forces in its wake, and from them derive an additional vigor. This was how Sauvages explained the origin of madness: a certain impression of fear is linked to the congestion or the pressure of a certain medullary fiber; this fear is limited to an object, as this congestion is strictly localized. In proportion as this fear persists, the soul grants it more attention, increasingly isolating and detaching it from all else. But such isolation reinforces the fear, and the soul, having accorded it too special a condition, gradually tends to attach to it a whole series of more or less remote ideas: "It joins to this simple idea all those which are likely to nourish and augment it. For example, a man who supposes in his sleep that he is being accused of a crime, immediately associates this idea with that of its satellites-judges, executioners, the gibbet." And from being thus burdened with all these new elements, involving them in its course, the idea assumes a kind of additional power which ultimately renders it irresistible even to the most concerted efforts of the will.

Madness, which finds its first possibility in the phenomenon of passion, and in the deployment of that double causality which, starring from passion itself, radiates both toward the body and toward the soul, is at the same time suspension of passion, breach of causality, dissolution of the elements of this unity. Madness participates both in the necessity of passion and in the anarchy of what, released by this very passion, transcends it and ultimately contests all it implies. Madness ends by being a movement of the nerves and muscles so violent that nothing in the course of images, ideas, or wills seems to correspond to it: this is the case of mania when it is suddenly intensified into convulsions, or when it degenerates into continuous frenzy. Conversely, madness can, in the body's repose or inertia, generate and then maintain an agitation of the soul, without pause or pacification, as is the case in melancholia, where external objects do not produce the same impression on the sufferer's mind as on that of a healthy man; "his impressions are weak and he rarely pays attention to them; his mind is almost totally absorbed by the vivacity of certain ideas."

Indeed this dissociation between the external movements of the body and the course of ideas does not mean that the unity of body and soul is necessarily dissolved, nor that each recovers its autonomy in madness. Doubtless the unity is compromised in its rigor and in its totality; but it is fissured, it turns out, along lines which do not abolish it, but divide it into arbitrary sectors. For when melancholia fixes upon an aberrant idea, it is not only the soul which is involved; it is the soul with the brain, the soul with the nerves, their origin and their fibers: a whole segment of the unity of soul and body is thus detached from the aggregate and especially from the organs by which reality is perceived. The same thing occurs in convulsions and agitation: the soul is not excluded from the body, but is swept along so rapidly by it that it cannot retain all its conceptions; it is separated from its memories, its intentions, its firmest ideas, and thus isolated from itself and from all that remains stable in the body, it surrenders itself to the most mobile fibers; nothing in its behavior is henceforth adapted to reality, to truth, or to prudence; though the fibers in their vibration may imitate what is happening in the perceptions, the sufferer cannot tell the difference: "The rapid and chaotic pulsations of the arteries, or whatever other derangement occurs, imprints this same movement on the fibers (as in perception); they will represent as present objects which are not so, as true those which are chimerical."

In madness, the totality of soul and body is parceled out: not according to the elements which constitute that totality metaphysically; but according to figures, images which envelop segments of the body and ideas of the soul in a kind of absurd unity. Fragments which isolate man from himself, but above all from reality; fragments which, by detaching themselves, have formed the unreal unity of a hallucination, and by very virtue of this autonomy impose it upon truth. "Madness is no more than the derangement of the imagination." In other words, beginning with passion, madness is still only an intense movement in the rational unity of soul and body; this is the level of unreason; but this intense movement quickly escapes the reason of the mechanism and becomes, in its violences, its stupors, its senseless propagations, an irrational movement; and it is then that, escaping truth and its constraints, the Unreal appears.

And thereby we find the suggestion of the third cycle we must now trace: that of chimeras, of hallucinations, and of error—the cycle of non-being.

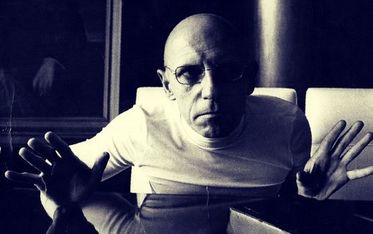

MICHEL FOUCAULT, MADNESS AND CIVILIZATION (A History of Insanity in the Age of Reason )

Translated from the French by RICHARD HOWARD Vintage Books, A DIVISION OF RANDOM HOUSE, New York

loading...

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Steven Craig Hickman - The Intelligence of Capital: The Collapse of Politics in Contemporary Society

Steven Craig Hickman - Hyperstition: Technorevisionism – Influencing, Modifying and Updating Reality

Archives

April 2020

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed