|

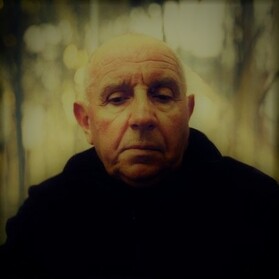

An Interview with Paul Virilio by Bertrand Richard "Terror is the realization of the law of movement." -Hannah Arendt Bertrand Richard: Paul Virilio, what do you mean by "administration of fear"? The expression seems to have a paranoid, Orwellian connotation and I would like to begin our conversation with it. Paul Virilio: When you and I began to discuss the project of doing this interview, the tide, The Administration of Fear, sprang to mind right away as a direct echo of the title of Graham Greene's well-known book, The Ministry of Fear. As you know, the novelist portrays London under the devastation of the German blitz in the Second World War. Greene's protagonist fights members of the Fifth Column, Nazis disguised as ordinary Londoners fighting a merciless war against the British from the inside. I lived through the ministry of fear as a child in Nantes after witnessing the Debacle; the Fifth Column, which had been formed during the Spanish Civil War, was omnipresent in everyone's thoughts and conversations. The presence of this sometimes imagined army of "saboteurs" and "traitors against the Nation" turned every neighbor, priest and shopkeeper into a potential enemy. The idea behind the Fifth Column was to sow panic; its message and power to create fear could be stated as: "We are not there, but we are already among you." We had had a first-hand experience of the Blitzkrieg, the lightning war. Nantes, 1940: one morning, we were informed that the Germans were in Orleans; at noon, we heard the sound of German trucks rolling through the streets. We had never seen anything like it. We had been living with memories of the First World War, a conflict that stretched out endlessly in time and between the positions occupied by the combatants-a war of attrition. Thirty years later, it only took a few hours for our city to be occupied. It is important to understand that occupation is both physical and mental (preoccupation). I use the expression "administration of fear" to refer to two things. First, that fear is now an environment, a surrounding, a world. It occupies and preoccupies us. Fear was once a phenomenon related to localized, identifiable events that were limited to a certain timeframe: wars, famines, epidemics. Today, the world itself is limited, saturated, reduced, restricting us to stressful claustrophobia: contagious stock crises, faceless terrorism, lightning pandemics, "professional" suicides (think of France Telecom, but we will come back to them). Fear is a world, panic as a "whole." The administration of fear also means that States are tempted to create policies for the orchestration and management of fear. Globalization has progressively eaten away at the traditional prerogatives of States (most notably of the Welfare State), and they have to convince citizens that they can ensure their physical safety. A dual health and security ideology has been established, and it represents a real threat to democracy. That is a brief explanation of my choice. Bertrand Richard: Can you elaborate on the connection between occupation (with fear representing the occupier today) and the notion of speed that you mentioned in relation to the Blitzkrieg of 1940? Paul Virilio: What is a Blitzkrieg? It is a military and technological phenomenon that occupies you in the blink of an eye, leaving you dumbfounded, mesmerized. It is also a phenomenon that introduced the extraordinary moment known as the Occupation. As you know, I think about speed, about speed that becomes increasingly faster through technological progress, with which it combines to form what I call a "dromosphere." I am convinced that just as speed led to the Germans' incredible domination over continental Europe in 1940, fear and its administration are now supported by the incredible spread of realtime technology, especially the new ICT or new information and communications technologies. This technological progress has been accompanied by real propaganda, notably in the way the media covers the new creations presented by Steve Jobs, Apple's all-powerful CEO. This combination of techno-scientific domination and propaganda reproduces all of the characteristics of occupation, both physically and mentally. Bertrand Richard: To continue the analogy, can we also see phenomena of resistance and collaboration today? Paul Virilio: To be a collaborator, there has to be an occupation, either intellectual (a preoccupation) or physical; the same is true for resistance fighters. During the Second World War, we were in the presence of a trinity: Occupation, Resistance and Collaboration. We can only understand the nature of fear within the complexity of an imposed situation like this. It was hard for me to understand as a child because we saw the enemy every day. They ate Lu cookies in the streets of Nantes; they bought meat at the same butcher shop as my mother; the ones who were bombarding and killing us were in fact our allies. Bertrand Richard: If I follow you, you mean that the administration of fear is also a problem of identity, and of identifying danger? Paul Virilio: Yes, it is a problem of identity in the proximity and interpenetration of different realities. Realities that can no longer be imagined in their conflict, which we imitated in our games as children, putting toy bayonets on our rifles to play Verdun-tragic but clear situations-but in their proximity. When I read Graham Greene's book, I found the expression "ministry of fear" to be particularly well chosen because it carries the administrative aspect of fear and describes it like a State. When you are occupied, fear is a State in the sense of a public power imposing a false and terrifying reality. Bertrand Richard: Why "false"? Paul Virilio: False because no one is inherently a collaborator, especially as a child, no more than anyone, is inherently a resistance fighter, even though the moral reality imposed on us follows this bipartition. For a child, an adult is at first surrounded by an aura of authority, no matter where he or she is from. Reality first appears as a trick. That is why I am sensitive to the current situation of the acceleration of reality. Not an "augmented" reality as the virtualists say but an accelerated reality, which is not the same thing. There is something at play here causing fear to become a constitutive element of life, relating it to the world of phenomena. And giving it a relationship with the world, a distorted relationship with Being-inthe-world. I am a phenomenologist, so I look back on a distorted world because the child that I once was lived in a world where you could not trust adults, which was very traumatic. Reality also appeared distorted on the level of physical fear: you could be killed by people who lived nearby and who appeared to be normal human beings, since we were in France and not in Poland where atrocities like the Warsaw ghetto were taking place. The occupiers were "normal" up until the head of the Kommandantur was assassinated in Nantes and the reprisals turned violent-I'm thinking of the prisoners executed at Chateaubriant, including Guy Moquet. The city was then in a state of siege and a curfew was imposed starting at 4 o'clock in the afternoon. Fear became physical, the fear of imminent death. Then, a few years later, we were subjected to extremely heavy Allied bombardments. Our allies were killing us and we saw truckloads of legless bodies, eviscerated torsos, decapitated heads drive past to the Saint-Jacques Hospital. The administration of fear is on both sides: it is an environment. Bertrand Richard: What happens to individual courage when fear is environmental and collective? Paul Virilio: For a young boy like myself, fear was a question of who was strongest and the question was limited to individual courage, skill and strength. But with the shelling and hostage taking, fear took hold of everyone, including the adults. Every building was shaking with fear. We were faced with collective fear, and it is impossible for children to be courageous in a time of collective terror, except by embracing sacrificial ideologies like patriotism or the kamikaze. What can be done with collective fear? It is a question of speed, which is essential to my work as a planner and philosopher. There was the Blitzkrieg and then the war of the radio waves. The speed of radio waves for communication and fighting immediately took on new importance on June 18, 1940 with General De Gaulle's call to arms. And it all took place in the same town, in the same street, in Nantes. Bertrand Richard: The reality you describe appears to be chaotic and indistinct. There is no distinction between things-it is a real hodge-podge. Is this an early farm of jean Baudrillard's "viral process of indistinction"? And how does one develop a capacity far judgment when things are so mixed up? Paul Virilio: First by taking refuge at the heart of the microcollectivity of the family, then the building or the town. They allow children to situate themselves. Towns are more protected than cities because the countryside is more isolated and occupied less strictly. Living in the countryside means being more in the resistance because there is less control. I lived for a time in Vertou, in 1943-44, in the Loire-Atlantique near Nantes: it was there that we met members of the Resistance. Getting outside the administration of fear took place in communities, first in families and then in villages. I sketched the anti-tank fortifications located south of Nantes in my school notebook and passed them on to the resistance. Bertrand Richard: Isn't it inappropriate to use the same expression "administration of fear"far both the tragic historical events of the Second World War and what we Westerners are experiencing today, facing considerable challenges but in a relatively protected and prosperous position? In short, can't you be accused of being overly dramatic? Paul Virilio: I don't think so. To explain myself, I would like to refer to a phrase from one of the most eminent post-war thinkers, Hannah Arendt. In other words, Hannah Arendt has had a much greater influence on contemporary thought than Martin Heidegger. With the philosopher Gunther Anders, her first husband, she revealed the shock and the nature of the totalitarian phenomenon. She is its most incisive philosopher and theorist, especially when she states in The Origins of Totalitarianism that "Terror is the realization of the law of movement." For someone like me who lived through the Blitzkrieg and the war of the radio waves, it is dear that terror is not simply an emotional and psychological phenomenon but a physical one as well in the sense of physics and kinetics, a phenomenon related to what I call the "acceleration of reality." Arendt uses the expression "law of movement" to refer to the fact that there is no relationship to terror without a relationship to life and speed. Terror cuts to the quick: it is connected to life and quickness through technology. You can see it in the image of a gazelle using its agility to escape a lion. Speed is a significant phenomenon that became my life's work. The "law of movement" theorized by Arendt is the law of speed. Soon after celebrating the end of the war, a "balance" of terror was established between the Western and Eastern Blocs, a reciprocal immobilization, suspended speed. After experiencing the wars of direct confrontation symbolized by Verdun and Stalingrad, we came into the idea of massive dissuasion with Hiroshima and Nagasaki. We lived under this regime of a balance of terror for almost forty years. The first real and symbolic explosion in Hiroshima opened the space of cosmic fear. Bertrand Richard: "Balance of terror" is an "unbalanced" expression. It makes security the "offipring of terror" to use philosopher Jean-Pierre Dupuy's expression. Fear as a generating principle. How can we think this incongruity? Paul Virilio: This "incongruity," as you say, is at the heart of the administration of fear. The "balance of terror" was first and foremost, concretely, a military balance based on the arms industry and the scientific complex. Let's remember that science started to become militarized in World War I with chemical warfare but was only truly militarized with the H-bomb, which was on an entirely different level as an absolute weapon. We must see reality as it is. Since Hiroshima, Western democracies and the USSR, followed by Russia, and the rest of the world by means of diplomatic alliances and preferences, have lived with a military regime overshadowing political life. We can graciously recognize that this would be in democracy's interest if it wanted to be preserved, but we must also admit that it created a politically uncomfortable situation. It is even politically incorrect because democracy, under this military-scientific regime, can only survive in an illusory and very partial manner. And I will remind you that the reason we did not have an atomic war is due more to a miracle of history than the supposed virtues of mutual dissuasion. Take the Cuban Missile Crisis. Arthur Schlesinger, Kennedy's advisor at the time, said that it was not only the most dangerous time of the Cold War but the most dangerous time in the history of humanity. It was two minutes to midnight on the Doomsday Clock, the timepiece invented in 1947 by physicists who were shocked by the atomic bombs dropped on Japan. Bertrand Richard: Robert McNamara, military adviser during the war in the Pacific and later Secretary of Defense under Kennedy, even said "We lucked out. " Paul Virilio: Yes, but political reality is rigged by military power. The military-industrial complex took control in the end. When he left the White House, Eisenhower, a specialist in military logistics, warned against the military-industrial complex and its increasing hold over all levels of decision making, and against the fact that it was becoming a univocal filter for reading the contemporary world. And Eisenhower knew just how much it threatened democracy. Bertrand Richard: In using the expression "military-industrial complex," you have no hesitation in sharing terminology favored by conspiracy theorists? Paul Virilio: I am not a conspiracy theorist; I only describe logics. This complex started to become dominant with the bomb because it took hold of science and contaminated it. To be precise, however, the word "scientific" is missing from the expression "military-industrial complex." No political philosophy emerged to counterbalance, manage or channel this ideological and logistical complex. To understand it, I think we need to remember how a major, historic rendezvous in the history of ideas was missed. In fact, in the early 20th century, the question of the relationship between philosophy and science became frayed: a misunderstanding occurred between two leading thinkers. The intellectual encounter between Henri Bergson, the theorist of duration, and Albert Einstein, the inventor of relativity, did not work. The two thinkers, both Jewish, both geniuses, were not able to understand each other when they met in Paris. Bergson did not interpret relativity in the same way as Einstein: he understood it from the perspective of the feeling of immediacy and the experience of time, not from the perspective of physics. Neither as special relativity, with the question of the respective position of two observers placed in situations of relative movement, nor from the point of view of the curve of space-time in general relativity. For me, this is the domination of the military-industrial complex: it is all the more frightening for political philosophy today because this philosophy has not thought about speed or speed articulated in space. Bertrand Richard: In terms of concrete political philosophy, what did we miss in the unproductive dialogue between Bergson and Einstein? Paul Virilio: The source of the misunderstanding between Bergson and Einstein was mainly the fact that the philosopher was talking about "vif"[vivid, lively] and the physicist was talking about "vite"[quick] and "vide"[vacuum] which have scientific validity but lead people to be anxious about life, towards doubt and the relativity oflife. It was a space-time that had until then escaped immediate consciousness; temporal compression crushed the euphoria of progress. Phenomenology, which could be hastily described as the science of phenomena as they are perceived by the consciousness, was caught short, and I am using this expression on purpose. I am a phenomenologist, a Bergsonian and Husserlian. Bergsonian because of the attention to the living; Husserlian because of the attention he gave to thinking our habitat, the Earth, as the space in and through which we experience our own body, most notably in one of his posthumous works "Overthrow of the Copernican theory in usual interpretation of a world view. The original ark, Earth, does not move." [TN-published in English under the title "Foundational Investigations of the Phenomenological Origin of the Spatiality of Nature"] Husserl asserted the inertia of being in the world, which makes it a world and not a flux. Today, the inertia of the instant (simultaneity of communications) dominates the inertia of place (sedentariness) and phenomenology has been caught short by the notion of speed, despite the "intuition of the instant" by Gaston Bachelard. Phenomenology has been unable to explain that speed is not a phenomenon but the relationship between phenomena. Speed is relativity and relativity is politics! To explain: ancient societies had varied and diverse chrono-politics: calendarial, liturgical, natural (the seasons), civil or religious (holidays), professional, with the rhythms of farmers and then craftspeople, etc. In the 20th century, we discovered and used the instantaneity offered by the absolute speed of waves: at this precise moment, philosophy was left behind. I was friends with Gilles Deleuze and Felix Guattari and we often remarked that the lack of a political economy of speed to follow the traditional political economy of wealth was and still remains the great drama of political thought. The administration of time and tempo escapes us. Tempo and rhythm. Dromology, the science of movement and speed, has therefore always been a musicology for me. My master, Vladimir Jankelevitch, was a prominent musicologist. Dromology is a question of rhythm, of the variety of rhythms, of chronodiversity. You can see that what I am trying to think about has nothing to do with deciding whether or not to decrease or increase the speed of the TGV. I am not part of an Ancients vs. Moderns debate between technophiles and technophobes. The stakes are on a completely different level: it is the question of the diversity of rhythms. Our societies have become arrhythmic. Or they only know one rhythm: constant acceleration. Until the crash and systemic failure. Bertrand Richard: Yet we are in an era of the balance of terror. Atomic weapons still exist, but their proliferation is relatively limited and slow, at a rate that the researcher Bruno Tertrais estimates to be approximately one new nuclear power every five or six years since the end of the 1940s. And the two blocs no longer exist. Isn't that enough for fear to ebb? Paul Virilio: No, because the first, largely unthought sequence constituted by the balance of terror, was followed by a second sequence characterized by the imbalance of "terrorist" terror. This is the key factor in the spread of contemporary terror. It is an imbalance because the proliferation of weapons of mass destruction has spread beyond the sphere of dissuasion between the blocs to threaten world peace (in particular, by means of radiological weapons, which are relatively more accessible than nuclear devices and can still render cities uninhabitable for a century). The initial events of this new phase called the "imbalance of terror" are of course the September 11, 2001 attacks in New York, followed three years later by the attack at Atocha Station in Madrid and then in London. How should we define the imbalance of terror? As the possibility for a single individual to cause as much damage as an absolute weapon. It is also the "making of fear" in the literal sense of the word, which is what terrorism does. The weapons are not necessarily sophisticated, but they are volatile, movable and frighteningly effective. The possibility of a total war caused by a single individual is frightening because it changes the traditional relationships of force as they have been experienced throughout most of human history. It has caused panic not only on the individual level but also a political panic that has lost all sense of scale, especially in the United States. Bertrand Richard: You are thinking of Donald Rumsfeld when he said that "the war on terror will be won when Americans and their children can again feel safe. " The American political scientist Benjamin R. Barber's response was that "no American child may feel safe in his or her bed if in Karachi and Baghdad, children don't feel safe in theirs. " Paul Virilio: Yes, speed causes anxiety by the abolition of space or more precisely by the failure of collective thinking on real space because relativity was never truly understood or secularized. It is why Francis Fukuyama was wrong in predicting the end of history. First of all, because there is something unnecessarily apocalyptic about his prognosis; second, because history continues with the march of time and human action; and third, because Fukuyama was misleading us and causing us to waste time. The question is not the end of history but the end of geography. My work on speed and relativity led me to suggest the notion of a "gray ecology" on the occasion of the Rio summit on the environment in 1992. Why "gray"? More than just a reference to Hegel's "gray ontology," it was a way for me to say that if green ecology deals with the pollution of flora, fauna and the atmosphere, or in fact with Nature and Substance, then gray ecology deals with the pollution of distance, of the life-size aspect of places and time measurement. Almost twenty years later, I fear that we have not made any further progress in understanding this pollution or the ways to reduce it.Yes, speed causes anxiety by the abolition of space or more precisely by the failure of collective thinking on real space because relativity was never truly understood or secularized. It is why Francis Fukuyama was wrong in predicting the end of history. First of all, because there is something unnecessarily apocalyptic about his prognosis; second, because history continues with the march of time and human action; and third, because Fukuyama was misleading us and causing us to waste time. The question is not the end of history but the end of geography. My work on speed and relativity led me to suggest the notion of a "gray ecology" on the occasion of the Rio summit on the environment in 1992. Why "gray"? More than just a reference to Hegel's "gray ontology," it was a way for me to say that if green ecology deals with the pollution of flora, fauna and the atmosphere, or in fact with Nature and Substance, then gray ecology deals with the pollution of distance, of the life-size aspect of places and time measurement. Almost twenty years later, I fear that we have not made any further progress in understanding this pollution or the ways to reduce it. True, but these two statements reveal the failure of the war on terror. Between them, the outraged and outrageous political reactions of neoconservative America and Great Britain have multiplied. The second Iraq War that removed Saddam Hussein revealed the grotesque face of a response that was literally a misstep, one war late and one terror removed. When you realize that a person can get on an airplane with explosives while his father is warning the CIA of his dangerousness and radicalization, it says a great deal about the means being deployed and the nature of the threat. The imbalance of terror has also taken an apocalyptic slant, in the religious sense of the word, a "revelation" in the extremely suggestive combination of man-made events and acts of nature, some of which come from what I would call the "ecological bomb." The major biblical myths were realized and concentrated in the first decade of the 21st century. Babel, with the collapse of the Twin Towers of the World Trade Center; the Flood with the combination of the tsunami in December 2004 and Katrina in 2005; and then the Exodus today with the probable submersion of coastal regions caused by the rising seas of global warming. I call it an ecological bomb in reference to the atomic bomb. I should also mention a second type, which is intimately connected to this time of the imbalance of terror. It is no longer atomic and not yet ecological but informational. This bomb comes from instantaneous means of communication and in particular the transmission of information. It plays a prominent role in establishing fear as a global environment, because it allows the synchronization of emotion on a global scale. Because of the absolute speed of electromagnetic waves, the same feeling of terror can be felt in all corners of the world at the same time. It is not a localized bomb: it explodes each second, with the news of an attack, a natural disaster, a health scare, a malicious rumor. It creates a "community of emotions," a communism of affects coming after the communism of the "community of interests" shared by different social classes. There is something in the synchronization of emotion that surpasses the power of standardization of opinion that was typical of the mass media in the second half of the 20th century. With the industrial revolution of the second half of the 19th century, the democracy of opinions flourished through the press, pamphlets and then the mass media-press, radio and television. This first regime consisted of the standardization of products and opinions. The second, current regime is comprised of the synchronization of emotions, ensuring the transition from a democracy of opinion to a democracy of emotion. For better or for worse. On the positive side, there are the examples of spontaneous generosity following disasters of all types; on the negative side, there is the instantaneous terror caused by an attack or a pandemic and the shortterm political actions that are taken in response. This shift is a significant event that places the emphasis on real time, on the live feed, instead of real space. And because the philosophical revolution of relativity did not take place, we have been unable to conceive of every space as a space-time: the real space of geography is connected to the real time of human action. With the phenomena of instantaneous interaction that are now our lot, there has been a veritable reversal, destabilizing the relationship of human interactions, and the time reserved for reflection, in favor of the conditioned responses produced by emotion. Thus the theoretical possibility of generalized panic. This is the second major explosion of the relationship with reality. Bertrand Richard: In your opinion, then, fear is the product of speed, which causes anxiety by the abolition of space, but is also amplified and vectorized by it. Paul Virilio: Yes, speed causes anxiety by the abolition of space or more precisely by the failure of collective thinking on real space because relativity was never truly understood or secularized. It is why Francis Fukuyama was wrong in predicting the end of history. First of all, because there is something unnecessarily apocalyptic about his prognosis; second, because history continues with the march of time and human action; and third, because Fukuyama was misleading us and causing us to waste time. The question is not the end of history but the end of geography. My work on speed and relativity led me to suggest the notion of a "gray ecology" on the occasion of the Rio summit on the environment in 1992. Why "gray"? More than just a reference to Hegel's "gray ontology," it was a way for me to say that if green ecology deals with the pollution of flora, fauna and the atmosphere, or in fact with Nature and Substance, then gray ecology deals with the pollution of distance, of the life-size aspect of places and time measurement. Almost twenty years later, I fear that we have not made any further progress in understanding this pollution or the ways to reduce it. Bertrand Richard: Do you mean a disappearance of reality, and do you agree here with Baudrillard and his theory of simulacra? I am thinking of his polemical article post-September 11 where he claimed that the iconographic power of the towers collapsing was such that it would cover up the event itself. Paul Virilio: More than Baudrillard, whose conclusions on simulacra I do not share, I would prefer to mention the book by Daniel Halevy published in 1947 called Essay on the Acceleration of History. In my opinion, we have left the acceleration of history and entered the acceleration of reality. When we speak of live events, of real time, we are talking about the acceleration of reality and not the acceleration of history. The classical definition of the acceleration of history is the passage from horses to trains, from trains to propeller planes and from planes to jet aircraft. They are within speeds that are controlled and controllable. They can be managed politically such that a political economy can be created to govern them. The current era is marked by the acceleration of reality: we have reached the limits of instantaneity, the limits of human thought and time. Bertrand Richard: The loss of place is joined by the loss of the body? Paul Virilio: Yes, and people are required to transfer their power of decision to automatic responses that can function at the immobile speed of instantaneity. The acceleration of reality is a significant mutation in History. Take the economy, for example. The economic crash that we experienced in 2007-2008 was a systemic crash with a history, a history going back to the early 1980s when global stock exchanges were first connected in real time. This connection, called "Program Trading," also had another, highly suggestive name: the "Big Bang'' of the markets. A first crash in 1987 confirmed and concretized the impossibility of managing this speed. The crash in 2008, which was partially caused by "flash trading," or very fast computerized listings done on the same computers as those used in national defense. Insider trading could occur very quickly. In fact, the shared time of financial information no longer exists; it has been replaced by the speed of computerized tools in a time that cannot be shared by everyone and does not allow real competition between operators. We are witnessing the end of the shared human time that would allow competition between operators having to reveal their perspective and anticipation (competition that is vital for capitalism to function) in favor of a nano-chronological time that ipso facto eliminates those stock exchanges that do not possess the same computer technology: automatic speculation in the futurism of the instant. This insider trading is an anamorphosis of time that has yet to be analyzed and sanctioned. Regulation becomes impossible because of this escape into the acceleration of reality. We can see how the absence of a political economy of speed is now literally causing not capitalism but turbo-capitalism to explode because it is caught at the limits of the acceleration of reality. I know that the current systemic crash, with the collapse of the housing bubble in 2007, is more complex and is leading us to rethink the relationship to value and accounting norms; however, the short-termism is obvious. The dilemma is that science itself has been deeply affected. Our reality has become uninhabitable in milliseconds, picoseconds, femtoseconds, billionths of seconds. Bertrand Richard: In an infinitely reduced space-time, does fear become fear of the lack of space, claustrophobia? Paul Virilio: Fear, as a product of spatio-temporal contraction, has paradoxically become cosmic. It was already cosmic at the time of the balance of terror. Now it has become cosmic in the sense of space-time: fear now covers the relationship to the universal. The universal was fundamentally peaceful as it was understood in the Enlightenment and JudeoChristian thought. Panic has now become something mystical. For example, do you remember how the end of communism saw the rise of a movement that had gone unnoticed: "cosmism"? Leonid Plioutch, a dissident, wanted to write a book on this phenomenon and on the Moscow philosophers who worked on it. Cosmism was the chimerical and expansionist desire to perpetuate the communist ideal in universal space as it was opened by the conquest of space. In the same way, with the crisis of capitalism, we can see how a "cosmic-theism" has developed with the same mystical fantasies. German philosopher Peter Sloterdijk, whom I admire, has done significant work on this subject and has even developed a philosophy of the space station. I see it as no more and no less than another example of contemporary illuminism. The current crisis is an anthropological crisis. Literally. Hegel's "beautiful totality" is becoming the "awful globality'' of the ecological crisis. Bertrand Richard: Isn't this fear the fear of losing reality, along with any control over it? Paul Virilio: Derealization is no more and no less than the result of progress. The defense of augmented reality, which is the ritual response of progress propaganda, is in fact a derealization induced by the success of the progress in acceleration and the law of movement that we mentioned at the start of this interview. This continual increase in speed has led to the development of a megaloscopy which has caused a real infirmity because it reduces the field of vision. The faster we go, the more we look ahead in anticipation and lose our lateral vision. Screens are like windshields in a car: with increased speed, we lose the sense of lateralization, which is an infirmity in our being in the world, its richness, its relief, its depth of field. We have invented glasses to see in three dimensions while we are in the process of losing our lateralization, our natural stereo-reality. Augmented reality is a fool's game, a televisual glaucoma. Screens have become blind. Lateral vision is very important and it is not by chance that animals' eyes are situated on the sides of their head. Their survival depends on anticipating surprise, and surprises never come head-on. Predators come from the back or the sides. There is a loss of the visual field and the anticipation of what really surrounds us. Yet this situation is not fatal. It would be if we pay no attention to it and speed is still not taken into account with wealth. I have always thought that political economy was invented by physiocrats, men of the body, human, humus, and hygiene. We lack a political economy of speed. I am not an economist, but one thing is clear: we will need one, or we will fall into globalitarianism, the "totalitarianism of totalitarianism." As a reminder, I believe that the mastery of power is linked to the mastery of speed. A world of immediacy and simultaneity would be absolutely uninhabitable. Bertrand Richard: How can a body or density remain in a purely informational logic? Do you share the idea that progress has something to do with our fate, which is to be unable to resist it? Paul Virilio: We must be able to dominate the domination of progress. There is a distinction between progress and propaganda. Speed, the cult of speed, is the propaganda of progress. The problem is that progress has become contaminated with its propaganda. The computer bomb exploded progress in its materiality, its substance in the sense of reality, geopolitics, temporal relationships, rhythm. To be clear, my fight is against the propaganda of progress and not against progress itself. I remember reading Signal during the Occupation; it was a newspaper that promoted the occupiers. I remember it very clearly: the power of domination and, moreover, the will to convince others of its merits had something very contemporary about it. Today, propaganda has replaced progress. In the word propaganda, we can recognize "propagation." In religious faith, there is propaganda fide, the spread of the catholic faith under the direction of the department of pontifical administration. Propagation and faith are of the same nature. Propaganda and faith are not of the same nature. Bertrand Richard: Propagandists and proselytizers are not the same ... Paul Virilio: Exactly. And propaganda comes directly from the fact that we did not take into account the phenomena of relativity that we have been talking about from the beginning. The damage of progress is the damage caused by propaganda. I have always said that I am not against new technologies; I am only against promoting them. How can we not be alarmed by the media storm that erupts with each new product released by the company with an apple as its logo? The media provides free promotion and participates in the mass illuminism which is at a far remove from information. It explains how augmented reality (the computerized technology that allows virtual images to be superposed onto natural perception) is passed off as progress in itself. Whereas these new perceptions come at a cost: the loss of a part of the field of perception, since augmented reality is nothing more than accelerated reality. from the book: The Administration Of Fear by Paul Virilio

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Steven Craig Hickman - The Intelligence of Capital: The Collapse of Politics in Contemporary Society

Steven Craig Hickman - Hyperstition: Technorevisionism – Influencing, Modifying and Updating Reality

Archives

April 2020

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed