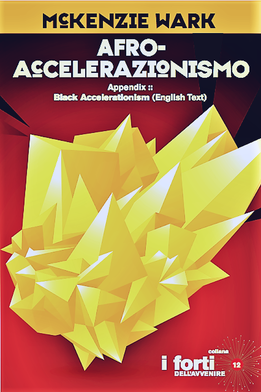

IndexForeword B/ACC Diaspora by Algorithmic Committee (for Decomputation) Black Accelerationism by McKenzie Wark Biography B/ACC Diasporaby Algorithmic Committee (for Decomputation) This essay of McKenzie Wark is of great significance for various reasons. It shows to an international audience a visionary and quite unique variation of the accelerationist thought: Black Accelerationism, whose pioneer and incessant agent is Kodwo Eshun. Black Accelerationism lingers on the most innovative text about such a diasporic tendency: More Brilliant than the Sun, edited in 1998 by Quartet Books. Eshun’s book has immediately become an «at light speed-thought book» (the author himself defined it as “speculative acceleration”) and the Quartet edition is today extremely difficult to find. For this reason Verso Books will republish it with a renewed version sometime in 2018. McKenzie Wark is brilliant in placing Eshun’s work and thought in the nineties/zeros when cyberpunk, drum and bass, Deleuze and Guattari, hackers, alter-net, Ccru and black mutant music offered a valid energetic alternative to the triumphant culture of tech-evangelists and dot.com markets. Against speculative bubbles and speculative contemporary thoughts of unproductive repetitive dualisms, McKenzie Wark offers a new plastic thought expressed by a black, afro-futuristic and afro-accelerationist culture, able to display imagination and amusement. Expression of a mutant pop culture made of comics, science-fiction and music, the black-accelerationist idea of future shows a deep intolerance to western normative regularizations, becoming at the same time perturbing, problematic and vibrantly lively. McKenzie Wark’s account on Black accelerationism represents the most seductive and catchy side of the accelerationist movement today, removing the tendency of flattening accelerationist thought to an «ideology museum» (race, nation, money, politics, etc.). It is thanks to this last irreverent act that Black Accelerationism becomes today a great political player and an incredible future force. BLACK ACCELERATIONISMby McKenzie Wark “Sensory language leaves us with no habit for lying. We are hostile aliens, immune from dying.” – The Spaceape If accelerationism has a key idea, it is that it is either impossible or undesirable to resist or negate the development of the commodity economy coupled with technology. Rather, it has to be pushed harder and faster, that it has to change more rather than less. It is an idea, a feeling, an orientation that might make most sense among those for whom the past was not that great anyway. Laboria Cuboniks’ text on xenofeminism would be one example of this. But in many ways the original and best text on accelerationism was about Blackness – Kodwo Eshun’s More Brilliant Than the Sun (Quartet 1998). Since accelerationists tend to be rather ignorant about their own past, this curious fact of the movement having an unacknowledged Black precursor is worth exploring. Eshun: “Everything the media warns you against has already been made into tracks that drive the dance floor.” (96) It’s helpful to make a preliminary distinction here between Black Accelerationism and Afrofuturism, although the former may in some ways be a subset of the latter. Black Accelerationism is a willful pushing forward which includes as part of its method an attempt to clear away certain habits of thought and feeling in order to be open to a future which is attempting to realize itself in the present. Afrofuturism is a more general category in which one finds attempts to picture or narrate or conceive of Black existence on other worlds or in future times which may or may not have an accelerationist will to push on. If Black Accelerationism is a particular temporal and spatial concept, Afrofuturism is a genre which includes both temporal and spatial concepts within the general cultural space of science fiction. Which in turn might be a subset of modernism, with its characteristically non-transitive approach to time. The term Afrofuturism was coined by Mark Dery, drawing on suggestions in the work of Greg Tate. It’s become a lively site of cultural production but also scholarly research, providing a frame for thinking about the science fiction writing of African American authors such as Samuel Delany and Octavia Butler and much else. It has also become a popular trope in contemporary cultural production, for example in music videos by Beyoncé, FKA Twigs and Janelle Monáe. Monáe’s video ‘Many Moons’ contains one of the key figures of the genre. It shows androids performing at an auction for wealthy clients, including white, vampiric plutocrats and a Black military-dictator type. The androids are all Black, and are indeed all Monáe herself. The android becomes the reversal, and yet also the equivalent, of the slave. The slave was a human treated as a non-person and forced to work like a machine; the android is an inhuman treated as a non-person but forced to work like a human. These figures have a deep past. But first, I want to explore one of their futures, or a related future. After writing More Brilliant than the Sun, Eshun co-founded the Otolith Group with Anjalika Sagar. The first three films they made together, Otolith parts I, II and III, are documented in the volume A Long Time Between Suns (Sternberg Press, 2009). Otolith provides both a ‘future’ and a different cultural space in which to think the Black accelerationism of Eshun’s earlier writing. Otolith is in the genre of documentary fiction or essay film, descended from the work of Chris Marker, Harun Farocki and the Black Audio Film Collective. The conceit organizing Otolith is a character who is a descendent of present-day Otolith co-founder Anjalika Sagar, who lives in orbit around our planet, and who is working through the archives of her own family. Otolith links the microgravity environment to planetary crisis, where orbital or agravic space is a heterotopia inviting heightened awareness of disorientation. “Gravity locates the human species.” (6) This is a speculative future in which the species bifurcates, those in microgravity function with a modified otolith, that part of the inner ear that senses the tilting of the body. Sagar’s imaginary future descendant looks back, through her own ancestors, to the grand social projects of the twentieth century: Indian and Soviet state socialism, the international socialist women’s movement and (as in Anna Tsing) the Non-Aligned Movement. One of Sagar’s ancestors had actually met Valentina Tereshkova, the first woman in space. Tereshkova was a former mill worker and (as in Platonov’s Happy Moscow) parachutist, destined for a grand career in Soviet public life. The last part of Otolith mediates on an unmade film by the great Satjayit Ray, The Alien. Its central conceit, of an alien lost on earth who is discovered by children, strangely enough turned up in the Hollywood film ET. Otolith speculate on whether Hindu polytheism foreclosed the space in which an Indian science fiction might have flourished. The popular Indian comic books that retell the stories of the Gods are indeed something like science fiction and call for a rethinking of the genre. Otolith also gestures toward American science fiction writer Roger Zelazny’s Lord of Light(1967), which imagines a quite different future to Otolith, but like it tries to decenter the imaginative future. In this book, the only survivors of a vanished earth are Hindu. Their high-tech society is also highly stratified. Its rulers have God-like powers and the technology to ‘reincarnate.’ The central character, described in the book as an ‘accelerationist’, challenges this class-bound order. It has often been observed that during the cold war, while much of American literature was basically white boys talking about their dicks, science fiction did a lot of the real cultural work. Zelazny’s book is not a bad example in how far science fiction could get in imagining a non-western world that was neither to be demonized or idealized, and whose agents of change were internal to it. One might note here in passing that the stand-out science fiction work of the last few years is Cixin Liu’s Three Body Problem and its sequels, whose story begins in the moment of China’s Cultural Revolution. Afrofuturism is a landscape of cultural invention that we can put in the context of a plural universe of imagined future times and other spaces, which draw on the raw material of many kinds of historical experience and cultural raw material. And just as Afrofuturism functions as a subset of science fiction modernities, there might also be many kinds of accelerationism. The posthuman ends up being more than one thing if one can get one’s head around currently existing humans as being more than one thing. The orbital posthuman of Otolith might in many ways repeat a figure from that little-known accelerationist classic, JD Bernal’s The World, The Flesh and the Spirit (1929). But it does so inflected by particular cultural histories. Which brings me to More Brilliant than the Sun (Quartet 1998). Like Paul B. Preciado’s Testo Junkie, it is a text whose strategies include putting pressure on language through neologisms and portmanteau constructs, in order to let the future into the present. Eshun sets himself against modes of writing about Black music that are designed to resist hearing anything new. “The future is a much better guide to the present than the past.” (-1) Thus, “the rhythmachine is locked in a retarded innocence.” (-7) You are not supposed to analyze the groove, or find a language for it. Music writing becomes a future shock absorber. “You reserve your nausea for the timeless classic.” (89) Eshun’s interest is rather in “Unidentified Audio Objects.” (-5) We no longer have roots we have aerials. Eshun is resistant to that writing that wants the authentic and the same in its music. That wants to locate it in organic community, whether in the Mississippi delta for the blues or the burning Bronx for hip hop. He is resistant to the validating figure of ‘the street’ as the mythical social or public place where the real is born. Eshun: “From the Net to arcade simulations games, civil society is all just one giant research-and-development wing of the military. The military industrial complex has advanced decades ahead of civil society, becoming a lethal military entertainment complex. The MEC reprograms predatory virtual futures. Far from being a generative source for pop culture, as Trad media still quaintly insists, the street is now the playground in which low-end developments of military technology are unleashed, to mutate themselves.” (85) As Black Lives Matter has so consistently confirmed. For Eshun, disco is “audibly where the 21st century begins.” (-6). Even if most genealogies of pop delete its intimations of the sonic diaspora of Afrofuturism. Like Paul Gilroy, Eshun thinks Black culture as diasporic rather than national, but unlike Gilroy, he is not interested in a critical negation of the limits of humanism in the name of a more expansive one. His Black culture “alienates itself from the human; it arrives from the future.” (-5) It refuses the human as a central category. If the human is not a given, then neither can there be a Black essence. There’s no ‘keeping it real’ in this book. The writer’s job is to be a sensor rather than a censor. The field of study here is not so much music itself as the ambiences music co-generates with spaces, sound systems, and indeed bodies. It’s not an aesthetics of music so much as what the late Randy Martin would have recognized as a kinaesthetics. One could even see it as a branch of psychogeography, but not of walking – of dancing. The dance does not reveal some aspect of the human, but rather has the capacity to make the human something else. Eshun follows Lyotard in extending Nietzsche’s insistence that the human does not want the truth, here the human craves the inauthentic and the artificial. This is the basis of its accelerationism: the objective is to encourage machine-made music’s “despotic drive” of music to subsume both its own past and the presence of the human body. (-4) Black accelerationism, operating mostly but not exclusively through music, aims “to design, manufacture, fabricate, synthesize, cut, paste and edit a so-called artificial discontinuum for the future rhythmachine.” (-3) As in Hiroki Azuma, machines don’t alienate people. They can make you feel more intensely. They enable a hyper-embodiment rather than disembodiment. I want to work backwards through the sonic material Eshun feels his way through, perhaps imagined through some equivalent future descendant of Eshun’s to the future descendent of his collaborator Sagar. We can already imagine a future in which the futures of Afrofuturism are no more, but which might be residues from which to create still others. Besides, it’s a matter of perspective. Rather than think of a future that extends and repeats a past, we could imagine a future that selects and edits from a past, according to selective habit as yet unknown. It’s the opposite of what Eshun, punning on Marshall McLuhan, calls “(r)earview hearing.” (68) What’s not to like about late nineties Detroit techno? Here we might start with what for Eshun was one of the end points. Drexciya is an unidentifiable sonic object that comes with its own Afrofuturist myth. The Drexciyans navigate the depths of the Black Atlantic. They are a webbed mutant marine subspecies descended from pregnant slaves who were thrown overboard during the middle passage. Drexciya use electronic sound and beats to replay the alien abduction of slavery as sonic fiction, or as what Sun Ra called an alterdestiny. As Lisa Nakamura shows, certain popular Afrofuturist material like the Matrix movies, make the Black or the African the more authentically human and rooted. What appeals to Eshun is the opposite claim: that Blackness can accelerate faster away from the human. It’s an embrace rather than a refutation of the slave-machine figure, pressing it into service in pressing on. There was a time when avant-garde music was beatless. Drum and bass went in the opposite direction: “drumsticks become knitting needles hitting electrified bedsprings at 180bpm.” (69) The sensual topology offered by 4hero or A Guy Called Gerald use drum machines not to mimic the human drummer but replace it, to create abstract sonic environments that call the body into machinic patterns of movement. “Abstract doesn’t mean rarified or detached but the opposite: the body stuttering on the edge of a future sound, teetering on the brink of new speech.” (71) Rhythm becomes the lead instrument, as on A Guy Called Gerald’s Black Secret Technology, (1995) “dappling the ears with micro-discrepancies…. When polyrhythm phase-shifts into hyper-rhythm, it becomes unaccountable, compounded, confounding. It scrambles the sensorium, adapts the human into a ‘distributed being’ strung out across the webbed spider-nets and computational jungles of the digital diaspora.” (76-77) One could say more about how quite particular musical technologies program in advance a kind of phase-space of possible sonic landscapes. The human sound-maker is then not the author but rather the output of the machine itself. For Eshun this is a way to positively value the figure of Blackness as close to the machine-like and remote from the fully ‘human.’ Such a construct of race rather over-values the human. And if whiteness is supposedly most close to the human, then there’s every reason to think less of the human as a category in the first place. This rhetorical move is central to Black accelerationism. The coupling of Blackness with the machinic is what is to be valued and accelerated, as an overcoming of both whiteness and the human. If there’s a sonic precursor and stimulator for that line of thought, its acid house music as a playing out of the unintended possibilities of the Roland TB-303 bass synthesizer. It was meant as a bass accompaniment for musicians to practice to, but sonic artists such as Phuture made it a lead instrument, exploring its potential not to imitate bass but to make otherworldly sounds. Eshun: “Nothing you know about the history of music is any help whatsoever.” (95) Eshun mostly works his way around hip hop, being rather disinterested in its claims to street authenticity, not to mention its masculine bravado. He makes an exception for the late eighties work of the Ultramagnetic MCs. Here the song is in ruins, language is reduced to phonemes. The rapper becomes an abstract sound generator, dropping science. Eshun quotes Paul Virilio from Pure War (62), to the effect that “science and technology develop the unknown.” (29). Science is associated not with what is demonstrated or proven but the opposite, which might be the condition of possibility of science in the more conventional sense. As is common among those who read a lot of Deleuze last century, Eshun favors an escape from the rational and the conscious, a slipping past the borders into the domain of affections and perceptions. In the language of Raunig and Lazzarato, it’s an attempt to slip past the individual into a space of dividual parts, in this case, of skins rippling with sonic sensation. It’s not consciousness raising so much as consciousness razing. Here, sound that works on the skin more than the ear, the animated body rather than the concentrating ear, might take the form of feedback, fuzz, static. In the eighties these were coming to be instruments in themselves rather than accidental or unwanted byproducts of instruments that made notes. One can hear (and feel) this in the Jungle Brothers or Public Enemy. The sound of a new earth, a Black planet. It is not the inhuman or the nonhuman or the over-human that is to be dreaded. What one might try to hear around is rather be the human as a special effect. “The unified self is an amputated self” (38) The sonic can produce what the textual always struggles to generate – a parallel processing of alternate states or points of view. This is not so much a double consciousness as the mitosis of the I. This is a sonic psychogeography that already heard the turbulent information sphere that Tiziana Terranova conceptualizes. But it’s more visceral than conceptual, or rather, both at once: “concepts are fondled and licked, sucked and played with.” (54) Of the recognized hip hop pioneers, the most lyrically and conceptually adventurous was the late Rammellzee, who worked in graffiti, sculpture and visual art as well as producing some remarkable writings, all bound together with a gothic futurist style he called Ikonoklast Panzerism. His work appeared always with a layer of armor to protect it from a hostile world. He already saw the hip hop world of the streets and the police as a subset of a larger militarization of all aspects of life. His particular struggle was already against the military perceptual complex, and his poetic figure for this was the attempt to “assassinate the infinity sign.” (34) Rammellzee ingested and elaborated on possibilities opened up by the discovery of the possibility latent in the direct-drive turntable of the breakbeat. ‘Adventures on the Wheels of Steel’ could stand-in as an emblem of that moment. Breakbeat opens up the possibility of the studio as a research center for isolating and replicating beats. The dj becomes a groove-robber rather than an ancestor worshipper. “Hip hop is therefore not a genre so much as an omni-genre, a conceptual approach towards sonic organization rather than a particular sound in itself.” (14) The turntable becomes a tone generator, the cut a command, discarding the song, automating the groove. It’s a meta-technique for making new instruments out of old ones. Of course, John Cage had already been there, arriving at the turntable not through encounters with gay disco so much as through a formalist avant-garde tradition. As Eshun wryly notes: “Pop always retroactively rescues unpop from the prison of its admirers.” (19) Couple the turntable with the Emulator sampler and you have a sonic production universe through which you can treat the whole of recorded sound as what Azuma thinks of as a database rather than as a grand narrative. Or rather, that techno-sonic universe can produce you. In Eshun’s perspective, the tech itself authors ways of being. The Emulator sampler discovers the sampled break and uses Marley Marl as its medium. New sounds are accidents discovered by machines. “Your record collection becomes an immense time machine that builds itself through you.” (20) The machine compels the human towards its parameters. The producer is rather like the gamer, as I understood the figure in Gamer Theory: an explorer of the interiority of the digital rather than romantic revolt beyond it. Digital sound reveals the body to itself, as a kind of sensational mathematics for kinaesthetes. If there is a ‘Delta blues origin story’ here for digital Black music, it is an ironic one. It is the German band Kraftwerk. But rather than delegitimizing Black digital music, Eshun has an affirmative spin on this. Black producers heard themselves in this European machine music. They heard an internal landscape toward which to disappear. Sonic engineers such as Underground Resistance volunteer for internal exile, for stealth and obfuscation. Even for passing as the machine: Juan Atkins releasing works under the name Model 500. “Detroit techno is aerial, it transmits along routes through space, is not grounded by the roots of any tree…. Techno disappears itself from the street, the ghetto and the hood…. The music arrives from another planet.” (101-102) A production entity like Cybotron “technofies the biosphere.” (29) Or escapes from it, building instead a city of time. “Escapism is organized until it seizes the means of perception and multiplies the modes of sensory reality… Sonic Fiction strands you in the present with no way of getting back to the 70s…. Sonic Fiction is the manual for your own offworld breakout, re-entry program, for entering Earth’s orbit and touching down on the landing strip of your senses…. To technofy is to become aware of the co-evolution of machine and human, the secret life of machines, the computerization of the world, the programming of history, the informatics of reality.” (103) The dj intensifies estrangement, creating alien sound design. Music making is deskilled, allowing for more hearing, less manual labor. The sound processes listeners into its content. Detroit techno comes with a plethora of heteronyms, in parallel rather than serial like Bowie. And it counter-programs against the sensuality of Funkadelic. “Techno triggers a de-libidinal economics of strict pulses, gated signals – with techno you dance your way into constriction.” (107) It favors the affectless voice over the glossolalia of soul. Techno is funk for androids escaping from the street and from labor. “Techno secedes from the logic of empowerment which underpins the entire African American mediascape.” (114) As in Donna Haraway, the machinic and Blackness are both liminal conditions in relation to the human, but treated not as an ironic political myth, but as program to implement with all deliberate speed. “There is a heightened awareness in Hip Hop, fostered through comics and sci-fi, of the manufactured, designed and posthuman existence of African-Americans. African aliens are snatched by African slave-traders, delivered to be sliced, diced and genetically designed by whiteface fanatics and cannibal Christians into American slaves, 3/5 of their standardized norm, their Westworld ROM.” (112) In somewhat Deleuzian terms, Eshun traces a line of flight from Blackness through the machine to becoming-imperceptible. “Machine Music therefore arrives as unblack, unpopular and uncultural, an Unidentified Audio Object with no ground, no roots and no culture.” (131) But far from erasing Blackness, this disappearance is only possible through Blackness or its analogs. The digital soundscape is a break in both method and style from the analog that it subsumed, and which in turn processed earlier forms of media technology after its own affordances. Key moments here might be George Clinton’s Funkadelic and Lee Perry’s Black Ark. These versions of analog signal processing took pop presence and processed it into an echo or loop. Space invades the texture of the song. Distortion becomes its own instrument. “Listening becomes a field trip through a found environment.” (66) Funkadelic was an alien encounter imagined through metaphor of the radio radio, connecting human-aliens to station WEFUNK, “home of the extraterrestrial brothers.” Its infectious, repetitive urding was to give in to the inhuman, to join the Afronauts funking up the galaxy. Built out of tape loops, doo-loops, mixadelics and advertising slogans for non-existent products. Underneath the off-pop hooks, Funkadelic altered the sensory hierarchy of the pop song. “The ass, the brain and the spine all change places…. The ass stops being the behind, and moves up front to become the booty.” (150) This was not the body shape proposed by pop. “Moog becomes a slithering cephalopod tugging at your hips.” (151) Funkadelic accelerated and popularized sonic concepts that in part came from jazz, or more specifically what Eshun calls the jazz fission of the 70s. This encompasses the cybernetic, space age jazz of George Russell, “a wraithscape of delocalized chimes… Russell’s magnetic mixology accelerates a discontinuum in which the future arrives from the past.” (4-5) Also in this bag are the 70s albums of Miles Davis and Herbie Hancock, where effects pedals become instruments in their own right. Here’s Eshun evoking the sound of Herbie Hancocks’s Hornets: “Moving through the echoplex, construction is cloned from a singular sensation into an environment that dunks you headfirst in a horde of heat-seeking killer bees.” (6) Effects defect from causes, detach from instruments. It’s the expansion of an era when industrial communication split sounds from sources, as R Murray Schafer has already suggested. It was hard to hear at first. Take, for instance Alice Coltrane’s controversial remixing of John Coltrane’s Living Space. Which in turn might be made possible by Sun Ra’s work from the mid-50s onwards, with his alternate Black cosmology. For Sun Ra, to be Black is not to be figuratively the Israelite, fleeing bondage, but to actually be descended from the Egyptians, to belong to a despotic power – which rules elsewhere in the galaxy. Where soul music would affirm Blackness as the legacy of the suffering human; Ra is an alien god from the future. This is not alienation by affirmation of the alien. Sun Ra lends himself to an Afrofuturist reading, which would highlight his claim to be from Jupiter, to be the author of an alter destiny. I think in Eshun there’s a more specifically Black accelerationist reading, or perhaps hearing, or maybe sensing. It’s not an alternative to this world, but a pressing on of a tendency, where through the exclusion from the human that is Blackness an escape hatch appears in an embrace of one other thing that is also excluded: the machinic. Would that it could have been closer to those other exclusions Haraway notes. Sun Ra’s Arkestra was for a long time a male monastic cult. Accelerationism is often presented as a desire for a superseding of a merely human model of cognition, but it is still rather tied to a valuing of cognition that has particular cultural roots. Perhaps cognition is not up to speed. Eshun: “There’s a sense in which the nervous system is being reshaped by beats for a new kind of state, for a new kind of sensory condition. Different parts of your body are actually in different states of evolution. Your head may well be lagging quite a long way behind the rest of your body.” (182) Otolith II posed two questions: “Capital, as far as we know, was never alive. How did it reproduce itself? How did it replicate? Did it use human skin?” (26) The operative word here is skin, implicated as it is in what Gilroy calls the crisis of raciology. Perhaps one could ask if capitalism has already superseded itself, and done so first by passing through the pores of the skin of those it designates others. But one might wonder whether, if this is not capitalism, it might not be something worse. Eshun already has an aerial attuned to that possibility, filtered through the sensibility of (for example) Detroit techno, with its canny intimations of the subsuming of the street into a militarized surveillance order, from which one had best discreetly retire. One could keep searching back through the database of Afrofuturism, beyond Eshun’s late twentieth century forays, as Louis Chude-Sokei does in The Sound of Culture. As it turns out, what is perhaps the founding text of Futurism is a perversely Afrofuturist one: Marinetti’s Mafarka: The Futurist (1910). It’s an exotic tale of an Islamic prince’s victory over an African army, and his desire to beget a son, part bird, part machine, who can rise up to conquer the sun — and is here perhaps the origin of the desire that gives Eshun his title. Or one might mention Samuel Butler’s anti-accelerationist Erewhon (1872), the ur-text on the human as the reproductive organ for the machine. Its imaginary landscape bares the traces of Butler’s experience in New Zealand, in the wake of colonial wars against the Maori. It may turn out that the whole question of acceleration is tied to the question of race. Haraway usefully thinks the spatial equivalence of the non-white, the non-man, the non-human in relation to a certain humanist language. But thought temporally, humanism has a similar problem. Spatially, it is troubled by what is above it (the angelic) or below it (the animal); temporally, it is troubled by what is prior to it (the primitive) or what supersedes it, including a great deal of race-panic about being overtaken by the formerly primitive colonial or enslaved other. Particularly of that other, in its unthinking, machine-like labor, starts to look like the new machines coming to replace the human. In this regard, the rhetorical strategy of Black accelerationism is to positively revalue what had been previously negative and racist figures. Such an intentional reversal of perspective may be a necessary step for any accelerationism that wants to do more than repeat the old figures, unawares. I would like to thank the Robert L. Heilbroner Center for Capitalism Studies at The New School. This piece was written during a writing retreat at the National Arts Club for grantees of the Center. Biography McKenzie Wark is the author of A Hacker Manifesto, Gamer Theory, 50 Years of Recuperation of the Situationist International and The Beach Beneath the Street, among other books. His latest published book is Twenty-One Thinkers for the Twenty First Century (Verso, 2017). He teaches at the New School for Social Research and Eugene Lang College in New York City. This essay is taken from:

0 Comments