|

by Ron Roberts

UNCLE AL AND UNCLE BILL IN THE TWENTY-FIRST CENTURY

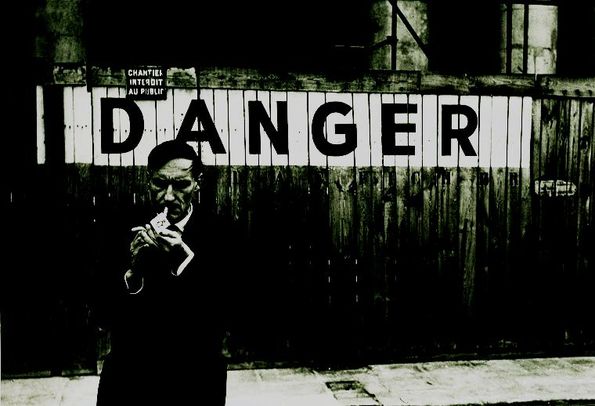

This chapter will construct a relationship between the figures of William S. Burroughs, the ‘High Priest’ of beatnik and punk culture, and Aleister Crowley, the ‘Great Beast’ of black magic. There is a sense in which the work of both authors connects into a larger, more occult network of thought than that which influences popular culture, resulting in a ‘feedback loop’, reprocessing certain aspects of their work and influencing everything from musical projects to contemporary retellings of major superhero stories. The start and end point of this loop is Burroughs’s treatment of magic(k)al practice, particularly in The Place of Dead Roads, and its relationship to Crowley’s esoteric writings.

William S. Burroughs and Aleister Crowley can be seen as dual influences in a number of late twentieth-century movements, both artistic and political. Artistically, the most famous of these is probably Genesis P-Orridge’s Temple ov Psychick Youth [sic] of the 1970s and 1980s, who were heavily influenced by, and worked with, Burroughs. They applied his processes to music, video and writing, while at the same time reading and absorbing the work of Crowley the magician. In a similar vein, Scottish comic-book writer Grant Morrison—called in to overhaul ailing marquee titles such as The Justice League of America (1997–2000), The X-Men (2001–2003) and The Flash (1997–98)—wrote a Burroughsian-influenced conspiracy theory title, The Invisibles (1994–2000). Morrison’s websites are hotbeds of debate concerning magical technique, Burroughs, Crowley, drugs, the Beats and related topics. Toward the end of The Invisibles’s (flagging) run, Morrison provided his readers with a page that was itself a mystical focus (or sigil) asking them to perform Crowleyian VIIIth Degree magic over it (a concept that we shall investigate later in this chapter), so that the comic might continue to be published.

It is not just in the realm of art and comic books that the presence of Burroughs and Crowley can be felt. Musically, Burroughs collaborated with figures as diverse as Kurt Cobain and The Disposable Heroes of HipHoprisy, while Crowley’s influence on bands such as Led Zeppelin is well known (see Davis 1985). Finally, while neither Burroughs nor Crowley developed a strongly self-conscious political stance, elements of their politics can be identified within the poppolitical movement of the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries, particularly in the anti-globalization movement associated with such figures as Noam Chomsky, Naomi Klein, Douglas Rushkoff and Howard Zinn. It can be observed that the majority of work produced by these artists and theorists responds, from the vantage point of various interrelated perspectives on the complexities of Western civilization, to what is rapidly coalescing into a ‘Westernized’ global order.

BURROUGHS AND THE GLOBAL ORDER

An entry point into a salient discussion of the ‘global order’ through the work of both Burroughs and Crowley must consider that their respective writings on the emergence of a consolidated global political and economic system seem to move in different directions: one emphasizing technocratic restrictions, the other delivering a cryptofascist attack on permissiveness and purposelessness. In Naked Lunch (1959), Doctor Benway is one of the ciphers through which Burroughs foretells the development of post-World War II Western society:

Benway is a manipulator and co-ordinator of symbol systems, an expert on all phases of interrogation, brainwashing and control […] ‘I deplore brutality’, he said. ‘It’s not efficient. On the other hand, prolonged mistreatment, short of physical violence, gives rise, when skillfully applied, to anxiety and a feeling of special guilt. A few rules or rather guiding principles are to be borne in mind. The subject must not realize that the mistreatment is a deliberate attack of an anti-human enemy on his personal identity. He must be made to feel that he deserves any treatment he receives because there is something (never specified) horribly wrong with him. The naked need of the control addicts must be decently covered by an arbitrary and intricate bureaucracy so that the subject cannot contact his enemy direct.’ (NL 20–1)

It could be said that something akin to these ‘control addicts’— variously identified in Burroughs’s fictions as ‘Nova criminals’, alien beings from Minraud and ‘vegetable people’—today administer and propagate a global sociopolitical hegemony. Like the ‘technocracy’ of Theodore Roszak and Herbert Marcuse, Burroughs sees a highly scientific and efficient anti-human impulse in twentieth-century society that stands as the crowning achievement of the Enlightenment process. ‘Under the technocracy’, writes Roszak, ‘we become the most scientific of societies; yet, like Kafka’s [protagonist in The Castle] K., men throughout the “developed world” become more and more the bewildered dependents of inaccessible castles wherein inscrutable technicians conjure with their fate’ (1969:13).

In The Place of Dead Roads, the order outlined in Naked Lunch has come to fruition; the later novel’s primary concern is with the main character’s struggle against the forces of a ‘global order’ that seeks to limit human potential and homogenize the human race. The novel chronicles the battle between the Johnson family (a term lifted from Jack Black’s 1926 vagrancy classic You Can’t Win describing those vagrants who abided by the rules of ‘tramp chivalry’), and the ‘shits’— the forces of ‘truth’, ‘justice’ and ‘moral order’. The Johnsons are a gang in the sense of the Old West, although with a conspiracy-theory spin that transforms them from honorable tramps into a global network of anti-establishment operatives, struggling against the depredations of the ‘powers that be’ (led in the novel by the bounty hunter Mike Chase). The villains in Burroughs’s novels often perform a double function, rapidly shifting from innocuous lowlifes to enemies of humanity, depending on the scene. In The Place of Dead Roads, this trope is noticeable in the shift from western to sci-fi story. It is telling that after a scene in which Kim and his friends invoke a major demon (PDR 92–4)—described with a careful eye to accuracy that draws from both the style of Crowley’s rituals and the fiction of H. P. Lovecraft—the narrative focus becomes more surreally ‘globalized’. Kim’s enemies cease to be homophobic cowboys, upstart gunslingers and lawmen; instead, a stranger and more insidious enemy is theorized: the body-snatching alien invaders of Nova Express. Old Man Bickford and his cronies operate as typical western villains, but their conflict with the Utopian program of Kim Carsons and his Johnson family betrays their identity as the ‘alien’ influence Burroughs sees as responsible for the propagation of Western capitalism and the denial of human potential. It is these ‘aliens’—alien in the sense that they seek to limit individual freedom through control mechanisms and an enforcement of ignorance—who constitute a new global order. For Burroughs, it is this anti-humanitarian impulse (typified by those who vehemently enforce laws surrounding ‘victimless crime’, and those whose nefarious schemes affect governments and nation states) that represents the greatest evil of the post-World War II order. Thus, the global order could constitute everything from a local group opposing a gay bar or hash café, through to the IMF or World Bank controlling the ‘development’ of a nation.

Writing in the first half of the last century, Crowley never formulated a picture of the modern industrial order in as much detail as Burroughs. However, in a preface to his cryptic The Book of the Law, he states:

Observe for yourselves the decay of the sense of sin, the growth of innocence and irresponsibility, the strange modifications of the reproductive instinct with a tendency to become bi-sexual or epicene, the childlike confidence in progress combined with nightmare fear of catastrophe, against which we are yet half unwilling to take precautions. Consider the outcrop of dictatorships […] and the prevalence of infantile cults like Communism, Fascism, Pacifism, Health Crazes, Occultism in nearly all its forms, religions sentimentalized to the point of practical extinction. Consider the popularity of the cinema, the wireless, the football pools and guessing competitions, all devices for soothing fractious children, no seed of purpose in them. Consider sport, the babyish enthusiasms and rages which it excites, whole nations disturbed by disputes between boys. Consider war, the atrocities which occur daily and leave us unmoved and hardly worried. We are children. (1938:13)

It is not too difficult to connect Burroughs’s ‘control addicts’ with the various mechanisms of control (or placation) that Crowley lists above. While Burroughs posits a class of controllers, Crowley tends to see humanity’s regression as a self-inflicted condition. Crowley posits a future Age of Aquarius, or ‘Aeon of Horus’, in which humanity will reach a stage of adolescence. At that time (some point in the twentieth century), decisions would be made affecting the evolution of the species over the next 2,000 years (the standard length of an astrological age); Crowley argues that without the widespread adoption of his Law of Thelema, ‘Do what thou wilt shall be the whole of the Law’, a combination of infantilism and dictatorial control will result in the stultification of the human race.

This theme of progressive human evolution is also evident in Burroughs’s fiction: his work prophesies a time when human culture will advance, becoming truly post-human, capable of transcending temporal restrictions and making the great leap into space. The first stage in such an evolution is the dissolution of boundaries: geographical, psychic and physical. This doctrine is at one with Crowley’s generalized transgressive maxim: ‘But exceed! Exceed!’ (1938:37). Significantly, these boundaries are located both within the self and imposed upon us by ‘control addicts’ like Doctor Benway. These boundaries, then, fulfill a role not unlike that of ideology, ‘fixing’ the identity of the individual through a combination of internal and external factors. And both Burroughs and Crowley suggest various strategies for the reshaping of the external world through the destruction of internal restriction; that is, the destruction of, or escape from, ‘ideology’ as a negative force. Common to both writers is a belief in the ‘magical’ power of language. Burroughs’s most famous dictum, of language as a virus, echoes Crowley’s maxim that the Will (or Word) of the magician can cause measurable changes in external reality, offering the possibility that the ‘language virus’, this ‘muttering sickness’, may be capable of transforming, rather than simply destroying, its host. SEX MAGIC

Early in Burroughs’s The Place of Dead Roads comes a sequence that distills a few centuries’ worth of cryptic alchemical and magical texts into a page or so of wild west science fiction:

Once he made sex magic against Judge Farris, who said Kim was rotten clear through and smelled like a polecat. He nailed a full-length picture of the Judge to the wall, taken from the society page, and masturbated.

in front of it while he intoned a jingle he had learned from a Welsh nanny:

Slip and stumble (lips peel back from his teeth) Trip and fall (his eyes light up inside) Down the stairs And hit the walllllllllllllllll!

His hair stands up on end. He whines and whimpers and howls the word out and shoots all over the Judge’s leg. And Judge Farris actually did fall downstairs a few days later, and fractured his shoulder bone. (PDR 19–20)

Kim Carsons, the novel’s time- and dimension-traveling assassin protagonist, ‘knew that he had succeeded in projecting a thought form. But he was not overly impressed […] Magic seemed to Kim a hit-and-miss operation, and to tell the truth, a bit silly. Guns and knives were more reliable’ (PDR 20).

Silliness aside, the above extract reflects the VIIIth Degree teachings of the Ordo Templi Orientis (OTO), an order of Knights Templar that, allegedly, brought back the secrets of Tantric Yoga (sexual yoga, where the object of intercourse is not ‘mere’ orgasm, but the ritual unification of participants as the male/female—Shiva/Shakti—principles of the universe) from India. At the invitation of the German leaders of the order (who due to the nature of the young Englishman’s knowledge initially believed him to have stolen their secrets), Crowley took over and restructured the British OTO in 1912, incorporating his own magical symbolism and interest in homosexual sex magic. Initiates were taught to project their sexual energy in a ritual context employing trappings such as mantras, incenses and visualizations to focus the energy and use it as fuel for the Will. Esoteric sex and masturbation becomes, then, ‘the Science and Art of causing change to occur in conformity with the Will’ (1929:xii). Sex as an instrument allowing ‘action at a distance’ is commonplace in Burroughs’s fiction, while the human Will is conceived of not as individual agency, but as part of a larger network. As Burroughs explains: ‘I think what we think of as ourselves is a very unimportant, a very small part of our actual potential […] We should talk about the most mysterious subject of all—sex. Sex is an electromagnetic phenomenon’ (Bockris 1981:60). (There are clear parallels between this conception of sexual energy and Wilhelm Reich’s theories of Orgone power—a topic of great interest to Burroughs—and Michael Bertiaux’s work with the sexual radioactivity he terms ‘Ojas’.

The ‘electromagnetic’—or otherwise mysterious, occult—force generated during sex, and sexual magic in particular, is an important weapon in the fight against the ‘shits’ on the side of order and repression. While Kim rejects magic as a means of performing relatively prosaic acts such as revenge, The Place of Dead Roads later advocates magic as a means for large-scale transformation of the human Will; indeed, in this novel Burroughs considers it necessary for the transformation of the human species. Using the example of the medieval assassins, a quasi-mythical sect led by the fabled Old Man of the Mountain, Hassan i Sabbah, Burroughs outlines the ways in which magical knowledge—especially the nourishment and cultivation of this electromagnetic sexual power—can be used to transform the consciousness into a new order of being. It is this new being that is capable of resisting control, placation and suppression: the homogenizing tools of the ‘control addicts’.

Hassan i Sabbah, a recurring figure in Burroughs’s fiction, acts as a Guardian Angel to Kim, his dictum ‘Nothing is true. Everything is permitted’ an early version of Crowley’s famous Law of Thelema: ‘Do what thou wilt shall be the whole of the Law’ (see Bockris 1981:116). In The Place of Dead Roads, the Assassins serve as an example of the next step in human evolution, while in earlier novels such as Nova Express (1964) it is the disembodied voice and shadowy presence of Sabbah that stands in opposition to the forces of the ‘control addicts’. The ‘Slave Gods’ of Western civilization demand nothing but servitude; Burroughs makes this clear in an eight-point description of the ‘objectives and characteristics’ of the Slave Gods and their alien followers (PDR 97). Primarily they must ensure that the human race remains earthbound; at all costs, mankind must be prevented from reaching higher realms of existence:

So the Old Man set up his own station, the Garden of Alamut. But the Garden is not at the end of the line. It might be seen as a rest camp and mutation center. Free from harassment, the human artifact [sic] can evolve into an organism suited for space conditions and space travel.

.There is a clear link between the figures of the assassins and comments made elsewhere by Burroughs concerning his beliefs for the future of mankind. When asked if he sees ‘Outer Space as the solution to this cop-ridden planet’, Burroughs replied, ‘Yeah, it’s the only place to go! If we ever get out alive … if we’re lucky’ (Vale and Juno 1982:21). Later in the same interview, Burroughs cites Dion Fortune’s Psychic Self Defence (1952) and David Conway’s Magic: An Occult Primer (1973) as essential texts for those wishing to resist the technocracy’s less obvious control mechanisms.

According to Burroughs, the transformative powers of the assassins came from the homosexual act—an act that does not depend upon dualism and rejects the creative principles of copulation. As we have already seen, the VIIIth Degree of OTO sex magic, with its emphasis on the projection of an outward manifestation of the Will, was rejected by Burroughs as too ‘hit-and-miss’. However, the homosexual act constitutes the XIth Degree of sex magic, almost universally acknowledged in occult circles as the most powerful form of Tantric energy manipulation. Modern magician and Voudon houngan Michael Bertiaux agrees: ‘Those who possess the technical knowledge admit that psychic ability is increased so that all of the forms of low mediumship and crude psychic powers are made perfect, while the higher psychic powers are fully manifested’ (Bertiaux 1988:44).

Crowley gives the theoretical formula of the XIth Degree in his Magick in Theory and Practice. He notes that

[s]uch an operation makes creation impossible […] Its effect is to consecrate the Magicians who perform it in a very special way […] The great merits of this formula are that it avoids contact with the inferior planes, that it is self-sufficient, that it involves no responsibilities, and that it leaves its masters not only stronger in themselves, but wholly free to fulfill their essential Natures. Its abuse is an abomination. (1929:27)

The homophobic stance adopted in the last sentence is clearly a statement Burroughs would have disagreed with; it is an example of the bisexual Crowley making his writing more ‘palatable’ to a wide audience. However, it suggests the same special power Burroughs attributes to the non-dualistic or non-reproductive use of sex magic.

To return to the magical universe explicated in The Place of Dead Roads, it becomes obvious that magic—especially sex magic—is an important weapon in the arsenal of resistance. Burroughs returns to the VIIIth Degree episode quoted earlier in this chapter, commenting that linear narrative itself is a trope used by any global order as an instrument of control. The Slave Gods and their minions, the control addicts, administrate the reality ‘film’ much as a person with a remote control has power over the progression of a videotaped movie. It is the role of the enlightened resistor to ‘cut up’ this straightforward A-B-C conception of time:

Take a segment of film:

This is a time segment. You can run it backward and forward, you can speed it up, slow it down, you can randomize it do anything you want with your film. You are God for that film segment. So ‘God’, then, has precisely that power with the human film. The only thing not prerecorded in a prerecorded universe is the prerecordings themselves: the master film. The unforgivable sin is to tamper with the prerecordings. Exactly what Kim is doing. (PDR 218)

Burroughs then explicitly links the transcendental powers of sex magic (specifically the episode discussed earlier) with this ‘tampering’ process—a means to resisting and transcending the global order of the twentieth and twenty-first centuries.

Despite specific differences that these sex magics maintain in their philosophy, each system proffers sex as a transformative ‘force’ capable of producing a potentially ‘resistant’ state of subjectivity. The vehicle for such change is the development of a ‘hidden’ body that coexists with the physical shell, a ‘ghost in the machine’, or Body of Light. BURROUGHS AND THE BODY OF LIGHT

In his book Queer Burroughs (2001), Jamie Russell draws attention to Burroughs’s use of Crowley’s term ‘Body of Light’. Crowley’s term (there are many others, such as the Voudon ‘Gwos Bon Anj’) describes the astral (or etheric) body that coexists alongside/in the normal, physical self. It is this astral form that possesses the capacity for magical acts and makes contact with other astral entities. Therefore, cultivation of the astral self, this ‘Body of Light’, is essential for acts of magical resistance.

Burroughs had a great interest in ‘other beings’, specifically those termed succubae and incubi, or ‘sexual vampires’. He theorized that these ‘sexual vampires’ are not necessarily negative in their relationships with human beings. In The Place of Dead Roads, Kim Carsons encounters such an entity, and finds the experience both pleasurable and rewarding. Toby, his incubus companion, is a ghostly figure that merges wholly with Kim as they make love: ‘Afterward the boy would slowly separate and lie beside him in the bed, almost transparent but with enough substance to indent the bedding’ (PDR 169). However, sexual contact with disembodied entities brings more than just physical pleasure—the relationship can lead to the accumulation of powerful allies in the fight against those forces seeking to replicate a restrictive form of global order—for example, those working to limit the potential of human evolution, keeping us ignorant and earthbound, or stuck in Crowley’s state of infantilism. Kim Carson finds himself surrounded by a small team of astral sex partners, each of whom brings a special talent to the fight against the enemies of the Johnson family (electronics work, demolition, causing accidents). These sexual familiars can be cultivated using the VIIIth and XIth Degree OTO ritual work: ‘He should make a point of organizing a staff of such spirits to suit various occasions. These should be “familiar” spirits, in the strict sense; members of his family’ (Crowley 1929:169).

Burroughs posits a more extreme use for such beings: as helpers and catalysts in the transformation from earthbound human to space-traveling post-human. Or, perhaps more radically, as potential allies in the conflict on earth:

BURROUGHS: We can only speculate as to what further relations with these beings might lead to, my dear. You see, the bodies of incubi and succubi are much less dense than the human body, and this is greatly to their advantage in space travel. Don’t forget, it is our bodies which must be weightless to go into space. Now, we make the connections with incubi and succubi in some sort of dream state. So I postulate that dreams may be a form of preparation, and in fact training, for travel in space […]

BOCKRIS: Are you suggesting that we collaborate with them in some way which would in fact benefit the future of our travel in space? BURROUGHS: Well, I simply believe that we should pay a great deal of attention to, and develop a much better understanding of, our relations with incubi and succubi. We can hardly afford to ignore their possible danger or use. If we reject a relationship with them, we may be placing our chances of survival in jeopardy. If we don’t dream, we may die. (Bockris 1981:189)

Burroughs’s conception of using these astral forms as aids to enlightenment/evolution is paralleled in Crowley’s work. The invocation of minor spirits from medieval grimoires aside, the central aim of Crowley’s magical practice was the ‘Knowledge and Conversation of the Holy Guardian Angel’ (HGA).9 This HGA is quite distinct from any notion of a Christian angel, representing instead that part of the Self that transcends the wheel of karma, or analogously, Burroughs’s ‘prerecorded film’. This perfected self exists beyond the physical boundaries of our shared reality, yet remains a part of the individual. To have the HGA ‘on side’, as it were, advances the Self toward what Crowley terms ‘disincarnation’. This disincarnation is a process of ‘removing […] impurities, of finding in [the] true self an immortal intelligence to whom matter is no more than the means of manifestation’ (1929:185). Thus, with the help of alien intelligences, or perhaps just a more rarefied form of our own mind made alien by its perfection, it may be possible to escape this ‘cop-ridden’ planet once and for all.

There is also a relationship between Burroughs’s ‘some sort of a dream state’ and the astral traveling of Crowley’s system of magic. Just as Kim Carsons seems to fold in and out of various dimensions cognizant with, yet not identical to, our own (from the haunted ‘wild west’ to a twentieth-century United Kingdom on the brink of revolution to futuristic bio-warfare tests in the Middle East), so Crowley tells us of various ‘planes’ of existence coterminous with our own. These planes can be accessed through dream, meditation and the techniques of sex magic discussed earlier. Once there, the magician can begin to master the various forces of the astral plane, meeting and recruiting the sorts of strange beings with which Burroughs populates his novels.

GUNS AND KNIVES ARE MORE RELIABLE

Crowley’s system of magic was intended solely for self-improvement. He eschewed the use of magic for ‘petty’ or mundane affairs; when your child is drowning, he stated, one does not attempt to summon water elementals. You must instead dive in. Similarly, in The Place of Dead Roads, Kim Carsons expresses a preference for direct methods, such as guns and knives, over magical manipulations. A sequence in the novel finds Kim working as an agent of the English Republican Party, a fictitious organization intent on removing the monarchy. In The Revised Boy Scout Manual (1970), a novel in the form of three onehour cassettes, Burroughs cheekily provides the blueprint for an armed insurrection and revolution, including random assassinations, biological warfare and the use of Reich’s concept of ‘Deadly Orgone Radiation’. However, the key to any successful revolution, according to this text, is the use of a right wing, crypto-fascist regime to wrestle power from the ‘democratic’ governance of the hegemonic ‘shits’:

Riots and demonstrations by street gangs are stepped up. Start random assassination. Five citizens every day in London but never a police officer or serviceman. Patrols in the street shooting the wrong people. Curfews. England is rapidly drifting towards anarchy. […] We send out our best agents to contact army officers and organize a rightist coup. We put rightist gangs into it like the Royal Crowns and the Royal Cavaliers in the street. 1. Time for ERP [English Republican Party]! 2. Come out in The Open! (1970:10)

Then the revolution changes tack, just as the reign of terror starts to turn into a Fourth Reich. Burroughs continues:

Why make the usual stupid scene kicking in liquor stores grabbing anything in sight? You wake up with a hangover in an alley, your prick tore from fucking dry cunts and assholes, eye gouged out by a broken beer bottle when you and your buddy wanted the same one—no fun in that. Why not leave it like it is? […]

[…] So we lay it on the line. ‘There’s no cause for alarm, folks, proceed about your daily tasks. But one thing is clearly understood—your lives, your bodies, your properties belong to us whenever and wherever we choose to take them.’ So, we weed out the undesirables and turn the place into a paradise … gettin’ it steady year after year … (1970:11)

In his blackly humorous way, Burroughs turns the military-industrial complex on itself, appropriating the methods of chemical warfare, guerilla fighting and urban pacification from their creators. Magic, mind control and meditation might be all well and good, but there is a voice in Burroughs’s fiction that calls out for physical, as well as psychic, resistance.

In a similar sense, The Book of the Law suggests the use of force as the only real means of removing the mechanisms of a technocratic global technocracy. While he did not share Burroughs’s passion for all things militaristic, the third chapter of the ‘Holy Book of Thelema’ issues the decree of Ra-Hoor-Khuit, the Egyptian god of war and vengeance. In his commentary, from The Law is For All, Crowley states, somewhat provocatively:

An end to the humanitarian mawkishness which is destroying the human race by the deliberate artificial protection of the unfit.

What has been the net result of our fine ‘Christian’ phrases? […] The unfit crowded and contaminated the fit, until Earth herself grew nauseated with the mess. We had not only a war which killed some eight million men, in the flower of their age, picked men at that, in four years, but a pestilence which killed six million in six months. Are we going to repeat the insanity? Should we not rather breed humanity for quality by killing off any tainted stock, as we do with other cattle, and exterminating the vermin which infect it? (1996:157)

The suspicious, crypto-fascist tenor of this passage undermines Crowley’s call to brotherly arms, though its rhetoric may suit the style of an ancient war god. Crowley had a complicated relationship with Fascism, admiring both Hitler and Mussolini, though it was the Italian dictator’s Fascist regime that was responsible for Crowley’s ejection from Sicily in 1923. Crowley also considered his Thelemic teachings to be the missing religious component of National Socialism, and tried to persuade German friends to open a direct channel of communication between himself and the German Chancellor. This relationship was tempered by his round rejection of Nazism’s racialist policies (fuel for a permanent Race War, Crowley surmised), although not, as is clear from the above quotation, their eugenics.

Both writers, then, play with rightist ideas—militarism, eugenics and genocide—as necessary steps in establishing an alternative future: that is, a society free of shits and control freaks and based on a respect for individual freedoms.

Of course, a tolerant society is required for what might be the greatest passion that the two figures had in common: the use of drugs. Burroughs’s relationship with pharmacopoeia hardly needs emphasizing; Naked Lunch was famously written under the effects of majoun, a fudge made from powerful hashish. He continued the use of various narcotics throughout his life. Works such as Junky, The Yage Letters and the Appendix to Naked Lunch outline his encounters with, and attitudes toward, various drugs.

Crowley was also well aware of the effects of illegal substances, going so far as to draw up a table of Kabbalistic correspondences detailing which drug to take to contact a particular god. His Diary of a Drug Fiend (1922a), made popular by a reprint in the 1990s, is a thinly disguised autobiographical account of his heroin and cocaine addiction. However, a text more analogous with Burroughs’s body of work is The Fountain of Hyacinth (1922b), a rare diary that details with candor his attempts to wean himself off cocaine and heroin.

LAST WORDS

The lives of both men present parallel obsessions with drugs, weird sex, weird philosophy, the writing of fiction and a rage against the order established by ‘the shits’. Both struggled with the various mechanisms of social control that were ranged against them, and provided ‘blueprints’ for those activists, adepts, agents and Johnsons seeking to continue the fight. Some points of convergence in these programs of resistance, such as developing the ‘Astral Body’ and the use of ritual magic, may seem outlandish, but they tap into that part of the human psyche that both wishes to believe in such things, and is capable of making such activities fruitful practice. Even so, from a twenty-first century viewpoint, this part of their blueprint may be dismissed as part of the New Age movement, laudable in intent, perhaps, but of no real practical consequence. However, their insistence on the same ‘last resort’—actual armed insurrection and extermination of the agents of global ideology—raises disturbing questions from our post-9/11 perspective. Abstract psychic dabbling is juxtaposed alongside rhetoric that seems to encourage a terroristic approach to anti-global protest and demonstration. That the writing and philosophy of both men still hold a fascination for activists wary of the West’s imperialist imperative—though no countercultural figure has yet to advocate armed resistance on anything like the same scale—stands as testament to the continuing importance of their outrageous lives and works.

Retaking the Universe (William S.Burroughs in the Age of Globalization)

Part 3: Alternatives: Realities and Resistance/The High Priest and the Great Beast at The Place Of Dead Roads /Edited by Davis Schneiderman and Philip Walsh First published 2004 by Pluto Press 345 Archway Road, London N6 5AA 22883 Quicksilver Drive, Sterling, VA 20166–2012, USA www.plutobooks.com

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Steven Craig Hickman - The Intelligence of Capital: The Collapse of Politics in Contemporary Society

Steven Craig Hickman - Hyperstition: Technorevisionism – Influencing, Modifying and Updating Reality

Archives

April 2020

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed