|

by Anthony Enns

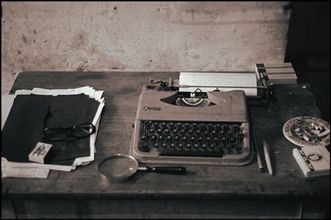

In January 1953, William S. Burroughs traveled to South America in search of yagé, a drug he hoped would allow him to establish a telepathic link with the native tribes. He documented this trip in a series of letters to Allen Ginsberg which he wrote on typewriters rented by the hour in Bogotà and Lima and which he eventually published as a book ten years later. Critics have interpreted this period as a seminal point in Burroughs’s career, largely due to the fact that the transcriptions of his drug experiences became the starting point for Naked Lunch. However, this experience also seems significant because it reveals Burroughs’s desire to achieve a primitive, pre-literate state—a goal which remained central to his work, but which later manifested in his manipulations of media technologies. Burroughs’s work thus offers a perfect illustration of Marshall McLuhan’s claim that the electric age would effect a return to tribal ways of thinking: ‘[S]ince the telegraph and the radio, the globe has contracted, spatially, into a single large village. Tribalism is our only resource since the electro-magnetic discovery’ (1962:219). And Burroughs’s rented typewriters seem to stand somewhere between these two worlds, as he used them to translate his primitive/mythic experiences into a printed book, a commodity more appropriate to Western culture and the civilized world of ‘typographic man’.

In this chapter, I argue that the representations of writing machines in Burroughs’s work, as well as his manipulations of writing machines in his working methods, demonstrate the effects of the electric media environment on subjectivity, as well as its broader impact on the national and global level. I further argue that McLuhan’s theories provide an ideal context for understanding the relationship between media, subjectivity, and globalization in Burroughs’s work, because they explain how the impact of the electric media environment on human consciousness is inherently linked to a wider array of social processes whose effects can be witnessed on both mental and geopolitical states. McLuhan and Burroughs were also contemporaries, and there is ample evidence that they drew ideas from one another’s work. McLuhan, for example, was the first critic to note that Burroughs’s novels effectively replicate the experience of the electric media environment (1964a:517), and he explicitly borrowed the term ‘mosaic’ from Naked Lunch to describe the format of television programming (1964b:204). In the original, unpublished version of The Third Mind, which Burroughs and Brion Gysin assembled from 1964 to 1965, Burroughs also included a paragraph from McLuhan’s The Gutenberg Galaxy, which claimed that electric media technologies were producing new mental states by releasing the civilized world from the visual emphasis of print (McLuhan 1962:183). However, despite the fact that Burroughs was clearly influenced by McLuhan, he also distanced himself from the overt optimism of McLuhan’s ‘global village’, thus avoiding the problem of technological determinism. In other words, rather than claiming that the electric media environment would automatically improve the human condition by enabling a greater degree of involvement and democracy, Burroughs repeatedly emphasized that this possibility was dependent on our ability to take control of the media. Burroughs’s representations and manipulations of writing machines thus prefigure much of the contemporary work concerning the potential uses of the Internet and the worldwide web as either corporate environments or new tools of democracy.

WRITING MACHINES AND THE ELECTRIC MEDIA ENVIRONMENT

Although several critics have already discussed Burroughs’s work in terms of the impact of media on subjectivity, these discussions generally focus on electric media technologies such as sound and film recording, and they often overlook mechanical machines like the typewriter. In her book How We Became Posthuman, for example, N. Katherine Hayles examines the impact of media on subjectivity in The Ticket that Exploded through Burroughs’s use of sound recording technology. She argues that Burroughs’s novel represents the tape recorder as a metaphor for the human body, which has been programmed with linguistic ‘pre-recordings’ that ‘function as parasites ready to take over the organism’ (1999:211). She also points out that the tape recorder subverts the disciplinary control of language by externalizing the mind’s interior monologue, ‘recording it on tape and subjecting the recording to various manipulations’, or by producing new words ‘made by the machine itself’ (1999:211). These manipulations reveal the ways in which electric media are capable of generating texts without the mediation of consciousness, thus enabling ‘new kinds of subjectivities’ (1999:217). Hayles therefore suggests that information technologies, for Burroughs, represent the threat of language to control and mechanize the body; at the same time, they can be employed as potential tools for subverting those same disciplinary forces.

Hayles’s conclusions could be amplified, however, by also examining Burroughs’s use of writing machines, which play a larger role in his work and in his working method. Hayles notes, for example, that Burroughs performed some of the tape recorder experiments he describes in The Ticket that Exploded, such as his attempts to externalize his sub-vocal speech or his experiments with ‘inching tape’, which are collected in the album Nothing Here Now but the Recordings, but even she admits that ‘paradoxically, I found the recording less forceful as a demonstration of Burroughs’s theories than his writing’ because ‘the aurality of his prose elicits a greater response than the machine productions it describes and instantiates’ (1999:216). This paradox is resolved, however, if one considers the typewriter as Burroughs’s primary tool for manipulating and subverting the parasitical ‘word’, and thus as the essential prototype for many of his theoretical media interventions. Throughout his life, Burroughs repeatedly emphasized that he was dependent on the typewriter and was incapable of writing without one: ‘I can hardly [write] with the old hand’ (Bockris 1981:1). Burroughs once attempted to use a tape recorder for composition, but this experiment proved to be a failure: ‘In the first place, talking and writing are quite different. So far as writing goes I do need a typewriter. I have to write it down and see it rather than talk it’ (Bockris 1981:6). When giving advice to young writers, Burroughs was also fond of quoting Sinclair Lewis: ‘If you want to be a writer, learn to type’ (AM 36). James Grauerholz notes that in 1950, Burroughs himself wrote his first book, Junky, ‘longhand, on lined paper tablets’, which were then typed up by Alice Jeffreys, the wife of a friend; however, Burroughs was soon ‘disappointed with Jeffreys’ work on the manuscripts […] which he felt she had overcorrected, so he bought a typewriter and learned to type, with four fingers: the index and middle finger of each hand’ (Grauerholz 1998:40). From the very beginning of his career, therefore, Burroughs was aware of the influence of writing technologies on the act of writing itself, and all of his subsequent works were mediated by the typewriter. This machine thus became a privileged site where the effects of media technologies were both demonstrated and manipulated.

The notion that the typewriter is inherently linked to the electric media environment—and, by extension, the digital media environment—has also become a popular theme in contemporary media studies. Friedrich Kittler, for example, argues that there was a rupture at the end of the nineteenth century when writing was suddenly seen as deficient and was stripped of its ability to store acoustic and optical information, resulting in their separation into three different media technologies: gramophone, film and typewriter (1999:14). Kittler also claims that the typewriter ‘unlinks hand, eye, and letter’, thus replicating the disembodying effects of electric media technologies (1990:195), and that the ultimate impact of this separation is that ‘the act of writing stops being an act […] produced by the grace of a human subject’ (1999:203–4). Scott Bukatman similarly points out that ‘[w]hat first characterizes typing as an act of writing is an effect of disembodiment’ (1993:634), and he extends this argument to the digital realm by suggesting that the typewriter ‘produces an information space divorced from the body: a proto-cyberspace’ (1993:635).

Burroughs’s work repeatedly illustrates the notion that writing machines have an effect on subjectivity by mediating the act of writing, and writers are repeatedly described as disembodied agents, ‘recording instruments’, or even ‘soft typewriters’, who simply transcribe and store written information. While writing Naked Lunch, for example, Burroughs claimed that he was an agent from another planet attempting to decode messages from outer space, and within the novel itself he describes the act of writing as a form of spiritual ‘possession’ (NL 200). This notion is not simply a metaphor for creativity, but rather it reappears in descriptions of his own writing process: ‘While writing The Place of Dead Roads, I felt in spiritual contact with the late English writer Denton Welch […] Whole sections came to me as if dictated, like table-tapping’ (Q xviii). The writer is thus removed from the actual composition of the text, and the act of writing becomes the practice of taking dictation on a typewriter. In the essay ‘The Name Is Burroughs’, Burroughs also reports a recurring ‘writer’s dream’ in which he reads a book and attempts to remember it: ‘I can never bring back more than a few sentences; still, I know that one day the book itself will hover over the typewriter as I copy the words already written there’ (AM 9). In ‘The Retreat Diaries’, he claims that ‘[w]riters don’t write, they read and transcribe’ (BF 189), and he also describes dreams in which he finds his books already written: ‘In dreams I sometimes find the books where it is written and I may bring back a few phrases that unwind like a scroll. Then I write as fast as I can type, because I am reading, not writing’ (190). Burroughs even incorporates these dreams into the narrative of The Western Lands, where a writer lies in bed each morning watching ‘grids of typewritten words in front of his eyes that moved and shifted as he tried to read the words, but he never could. He thought if he could just copy these words down, which were not his own words, he might be able to put together another book’ (WL 1–2). The act of typing thus replaces the act of writing, because the words themselves have already been written and the writer’s job is simply to type them out.

By disembodying the user and creating a virtual information space, Burroughs’s writing machines also prefigure the globalizing impact of electric media technologies. John Tomlinson, for example, argues that contemporary information technologies have a ‘deterritorializing’ effect because ‘they lift us out of our cultural and indeed existential connection with our discrete localities and, in various senses, open up our lifeworlds to a larger world’ (1999:180). McLuhan also points out that the electric media environment not only fragments narrative and information, but also reconfigures geopolitical power. According to McLuhan, for example, the visual emphasis of typography led to both individualism and nationalism, because the printed book introduced the notion of point of view at the same time that it standardized languages: ‘Closely interrelated, then, by the operation and effects of typography are the outering or uttering of private inner experience and the massing of collective national awareness, as the vernacular is rendered visible, central, and unified by the new technology’ (1962:199). Electric media, on the other hand, represent a vast extension of the human nervous system, which emphasize the auditory over the visual and global awareness over individual experience: ‘[W]ith electricity and automation, the technology of fragmented processes suddenly fused with the human dialogue and the need for over-all consideration of human unity. Men are […] involved in the total social process as never before; since with electricity we extend our central nervous system globally, instantly interrelating every human experience’ (McLuhan 1964b:310–11). This leads to a greater degree of interdependence and a reduction in national divisions, because ‘[i]n an electrically configured society […] all the critical information necessary to manufacture and distribution, from automobiles to computers, would be available to everyone at the same time’, and thus culture ‘becomes organized like an electric circuit: each point in the net is as central as the next’ (McLuhan and Powers 1989:92). The absence of a ‘ruling center’, McLuhan continues, allows hierarchies to ‘constantly dissolve and reform’, and information technologies therefore carry the threat of ‘politically destabilizing entire nations through the wholesale transfer of uncensored information across national borders’ (McLuhan and Powers 1989:92). Rather than seeing this development as essentially negative, however, McLuhan adds that it will result in ‘a dense electronic symphony where all nations—if they still exist as separate entities—may live in a clutch of spontaneous synesthesia, painfully aware of the triumphs and wounds of one other’ (McLuhan and Powers 1989:95).

Burroughs also illustrates the deterritorializing effects of media technologies, and he frequently refers to the construction of national borders and identities as simply a function of global systems of control and manipulation. In his essay ‘The Bay of Pigs’, for example, Burroughs writes:

There are several basic formulas that have held this planet in ignorance and slavery. The first is the concept of a nation or country. Draw a line around a piece of land and call it a country. That means police, customs, barriers, armies and trouble with other stone-age tribes on the other side of the line. The concept of a country must be eliminated. (BF 144)

The process of nation-building, in other words, is nothing more than the exercise of control. In ‘The Limits of Control’, Burroughs also points out that ‘the mass media’ has the power to spread ‘cultural movements in all directions’, allowing for the cultural revolution in America to become ‘worldwide’ (AM 120). The mass media therefore presents the possibility of an ‘Electronic Revolution’, which would not only cross national borders but also eliminate them (Job 174–203). By creating a sprawling, virtual information space, Burroughs’s novels illustrate the ways in which media technologies could potentially fragment national identities and global borders; they also reveal the interconnections between information technologies and world markets, where cultural and economic exchanges gradually become inseparable.

THE ADDING MACHINE AND BUREAUCRATIC POWER

Bukatman’s claim that the virtual information space of the typewriter is linked to the modern development of cyberspace can be most clearly seen by tracing the history of the Burroughs Adding Machine, which was patented by Burroughs’s paternal grandfather in 1885. The Adding Machine was a device for both calculating and typing invoices, and thus it shared many common features with the typewriter, including a ribbon reverse that later became standard on all typewriters. Although the typewriter was often seen as a separate technology because it was designed for business correspondence rather than accounting, a brief look at the history of the Burroughs Adding Machine Company indicates that the divisions between calculating and typing machines were never that clearly defined. In the 1920s, for example, the company also marketed the MoonHopkins machine, which combined the functions of an electric typewriter and a calculating machine, and in 1931 it even began producing the Burroughs Standard Typewriter. This merging of calculating and typing machines reached its full realization with the development of business computers in the early 1950s, and the Burroughs Adding Machine Company was also involved in the earliest stages of this transition. In 1951, for example, it began work on the Burroughs Electronic Accounting Machine (BEAM), and in 1952 it built an electronic memory system for the ENIAC computer. In 1961 it also introduced the B5000 Series, the first dual-processor and virtual memory computer, and in 1986 it merged with Sperry to form the Unisys Corporation, which released the first desktop, single-chip mainframe computers in 1989. The Adding Machine and the typewriter thus both stand at the beginning of a historical trajectory, where the distinction between words and numbers became increasingly blurred and where typing gradually transformed into ‘word processing’.

Burroughs clearly shares the legacy of this joint development of calculating and typing machines, as well as the development of a powerful corporate elite in America. The adding machine makes frequent appearances in his work, where it often represents the manipulative and controlling power of information. In The Ticket that Exploded, for example, Burroughs defines ‘word’ itself as ‘an array of calculating machines’ (TE 146). The novel also employs the linear, sequential and standardizing functions of calculating and typing machines as a metaphor to describe the mechanization of the body, or ‘soft typewriter’. The narrator claims, for example, that the body ‘is composed of thin transparent sheets on which is written the action from birth to death—Written on “the soft typewriter” before birth’ (TE 159). Tony Tanner points out that the ‘ticket’ in the title of the novel also ‘incorporates the idea that we are all programmed by a prerecorded tape which is fed into the self like a virus punchcard so that the self is never free. We are simply the message typed onto the jelly of flesh by some biological typewriter referred to as the Soft Machine’ (1971:135). The ‘soft typewriter’ therefore represents the body as an information storage device, upon which the parasitical ‘word’ has been inscribed. The fact that the Burroughs Adding Machine Company also produced ticketeers and was an early innovator in computer punch card technology further emphasizes this notion of the parasitical ‘word’ as a machine or computer language—a merging of words and numbers into a system of pure coding designed to control the functions of the machine.

There are also moments in Burroughs’s work when writing machines appear synonymous with the exercise of bureaucratic power, as can be seen in his description of the nameless ‘Man at The Typewriter’ in Nova Express, who remains ‘[c]alm and grey with inflexible authority’ as he types out writs and boardroom reports (NE 130). This connection between machines and bureaucratic power is also illustrated in The Soft Machine, where Mayan priests establish an oppressive regime based on an information monopoly. They employ a regimented calendar in order to manipulate the bodies and minds of the population, and access to the sacred codices is strictly forbidden: ‘[T]he Mayan control system depends on the calendar and the codices which contain symbols representing all states of thought and feeling possible to human animals living under such limited circumstances—These are the instruments with which they rotate and control units of thought’ (SM 91). The narrator repeatedly refers to this system as a ‘control machine’ for the processing of information, which is emphasized by the fact that the priests operate it by pushing ‘buttons’ (SM 91), like a typewriter or a computer. This connection between writing machines and bureaucratic authority is extended even further when the narrator goes to work at the Trak News Agency, whose computers actually invent news rather than record it. The narrator quickly draws a parallel between the Mayan codices and the mass media: ‘I sus [sic] it is the Mayan Caper with an IBM machine’ (SM 148). In other words, like the Mayan priests, who exercise a monopoly over written information in order to control and manipulate the masses, the Trak News Agency similarly controls people’s perception of reality through the use of computers: ‘IBM machine controls thought feeling and apparent sensory impressions’ (SM 148–9).

The notion that the news industry manipulates and controls people’s perceptions of reality is a recurring theme throughout Burroughs’s work. In The Third Mind, for example, he writes:

‘Reality’ is apparent because you live and believe it. What you call ‘reality’ is a complex network of necessity formulae…association lines of word and image presenting a prerecorded word and image track. How do you know ‘real’ events are taking place right where you are sitting now? You will read it tomorrow in the windy morning ‘NEWS’…(3M 27)

He also cites two historical examples where fabricated news became real: ‘Remember the Russo-Finnish War covered from the Press Club in Helsinki? Remember Mr. Hearst’s false armistice closing World War I a day early?’ (3M 27). In the chapter ‘Inside the Control Machine’, Burroughs more explicitly argues that the world press, like the Mayan codices, functions as a ‘control machine’ through the same process of repetition and association:

By this time you will have gained some insight into the Control Machine and how it operates. You will hear the disembodied voice which speaks through any newspaper on lines of association and juxtaposition. The mechanism has no voice of its own and can talk indirectly only through the words of others…speaking through comic strips…news items…advertisements…talking, above all, through names and numbers. Numbers are repetition and repetition is what produces events. (3M 178)

Like the Mayan codices, therefore, the modern media also illustrates the merging of words and numbers in a machinic language of pure control. Burroughs adds, however, that the essential difference between these two systems is that the ‘Mayan control system required that ninety-nine percent of the population be illiterate’ while ‘the modern control machine of the world press can operate only on a literate population’ (3M 179). In other words, the modern control machine is an extension of the printing press because it uses literacy in order to maintain social hierarchies and keep readers in a passive state of detachment. In order to overthrow these hierarchies, it is therefore necessary not simply to develop the literacy skills the Mayans lacked, but also to subvert the control machine itself and the standards of literacy it enforces.

THE ‘FOLD-IN’ METHOD AND AUDITORY SPACE

The narrator of The Soft Machine quickly discovers that understanding the nature of the Trak News Agency’s control machine is the first step to defeating it: ‘Whatever you feed into the machine on subliminal level the machine will process—So we feed in “dismantle thyself” […] We fold writers of all time in together […] all the words of the world stirring around in a cement mixer and pour in the resistance message’ (SM 149). In other words, the narrator is able to dismantle the control system by manipulating the writing machine and disrupting its standard, linear sequence of information. This manipulation involves the use of a technique Burroughs referred to as the ‘cut-up’ or ‘foldin’ method: ‘A page of text—my own or someone else’s—is folded down the middle and placed on another page—The composite text is then read across half one text and half the other’ (3M 95–6). Burroughs frequently employed this method in his own work, and it is perhaps the clearest example of how the typewriter creates ‘new kinds of subjectivity’ by displacing the author as the controlling consciousness of the text. In a 1965 Paris Review interview, Burroughs explained the essential difference between this method and simply free associating at the typewriter: ‘Your mind simply could not manage it. It’s like trying to keep so many chess moves in mind, you just couldn’t do it. The mental mechanisms of repression and selection are also operating against you’ (Knickerbocker 1965:25). The ultimate goal of this technique, in other words, is to short-circuit the literate mind and use the typewriter to achieve a more primitive state of awareness, which McLuhan describes as precisely the effect of the electric media environment.

Burroughs’s justification for the ‘fold-in’ method also emphasizes the basic inadequacy of print in comparison to developments in other media: ‘[I]f writing is to have a future it must at least catch up with the past and learn to use techniques that have been used for some time past in painting, music and film’ (3M 95). Burroughs thus saw this method as enabling the typewriter to manifest the properties of other media, including sound recording. This connection between the typewriter and sound may appear confusing, as his novels remain essentially visual, but McLuhan points out that the distinction between visual and auditory space actually refers to the way in which media technologies structure information:

Television, radio and the newspaper […] deal in auditory space, by which I mean that sphere of simultaneous relations created by the act of hearing. We hear from all directions at once; this creates a unique, unvisualizable space. The all-at-once-ness of auditory space is the exact opposite of lineality, of taking one thing at a time. It is very confusing to learn that the mosaic of a newspaper page is ‘auditory’ in basic structure. This, however, is only to say that any pattern in which the components coexist without direct lineal hook-up or connection, creating a field of simultaneous relations, is auditory, even though some of its aspects can be seen. The items of news and advertising that exist under a newspaper dateline are interrelated only by that dateline. They have no interconnection of logic or statement. Yet they form a mosaic or corporate image whose parts are interpenetrating […] It is a kind of orchestral, resonating unity, not the unity of logical discourse. (McLuhan 1963:43)

Burroughs’s ‘fold-in’ method thus transforms standardized, linear texts into a ‘mosaic’ of information, which parallels the structure of television, radio, and newspapers. Even though Burroughs’s ‘cut-up’ novels remain essentially visual, they create an auditory space because they provide connections between texts that are not based on ‘logic or statement’, and they behave more like the ‘sphere of simultaneous relations created by the act of hearing’. Such an understanding of auditory space helps to explain Burroughs’s notion of the ‘fold-in’ method as manifesting the properties of music, or McLuhan’s paradoxical notion of the typewriter as both a tool that regulates spelling and grammar and ‘an oral and mimetic instrument’ that gives writers the ‘freedom of the world of jazz’ (1964b:230).

The function of this method can be most clearly seen in The Ticket that Exploded, where the narrator describes a ‘writing machine’ that

shifts one half one text and half the other through a page frame on conveyor belts […] Shakespeare, Rimbaud, etc. permutating through page frames in constantly changing juxtaposition the machine spits out books and plays and poems—The spectators are invited to feed into the machine any pages of their own text in fifty-fifty juxtaposition with any author of their choice any pages of their choice and provided with the result in a few minutes. (TE 65)

The machine thus performs the ‘fold-in’ method by fragmenting and rearranging texts, and it further disrupts the written word through the use of ‘calligraphs’: ‘The magnetic pencil caught in calligraphs of Brion Gysin wrote back into the brain metal patterns of silence and space’ (TE 63). The possibility of ‘silence and space’, therefore, is represented through a break with print technology. This is most clearly illustrated on the last page of the novel—an actual calligraph composed by Brion Gysin, in which English and Arabic words alternate in various permutations of the phrase ‘Silence to say good bye’ (TE 203). The function of the machine is thus mirrored in the construction of the book itself, which was also composed using the ‘fold-in’ method and contains passages spliced in from other authors, including lines from Shakespeare’s The Tempest. Because the novel contains the formula for its own selfgenerating reproduction, Gérard-Georges Lemaire uses the term ‘writing machine’ interchangeably to refer to both the content and method of Burroughs’s work, and he points out that Burroughs’s machine not only ‘escapes from the control of its manipulator’, but ‘it does so in that it makes it possible to lay down a foundation of an unlimited number of books that end by reproducing themselves’ (3M 17). In other words, the parasitical ‘word’ is externalized from the writer’s own consciousness and reproduces itself in a series of endless permutations.

TYPESETTING EXPERIMENTS, THREE-COLUMN CUT-UPS AND THE GRID

Another method Burroughs employs to transform the printed word into an auditory space can be seen in his typesetting experiments, which were clearly inspired by the structure of newspapers and magazines. By presenting a series of unrelated texts in parallel columns, the newspaper suggests interconnections which are not based on logic or reason, and many of Burroughs’s stories from the 1960s and early 1970s reveal a growing interest in the effects of typesetting, one example being ‘The Coldspring News’. When this piece was originally published in White Subway, it was divided into two columns, and the sections contained bold titles, thus imitating newspaper headlines (WS 39, see BF for a reprint without the threecolumn format). The title of the story was also designed to resemble a masthead, with Burroughs listed as ‘Editor’ rather than author (WS 39). Subsequent editions removed this formatting, but Robert Sobieszek points out that Burroughs continued these experiments in his collages, many of which ‘were formatted in newspaper columns and often consisted of phrases rearranged from front pages of the New York Times along with photos or other illustrations’ (1996:55). Sobieszek also notes that in 1965 Burroughs created his own version of Time magazine, including

a Time cover of November 30, 1962, collaged over by Burroughs with a reproduction of a drawing, four drawings by Gysin, and twenty-six pages of typescripts comprised of cut-up texts and various photographs serving as news items. One of the pages is from an article on Red China from Time of September 13, 1963, and is collaged with a columnal typescript and an irrelevant illustration from the ‘Modern Living’ section of the magazine. A full-page advertisement for JohnsManville products is casually inserted amid all these texts; its title: ‘Filtering’. (1996:37)

These experiments therefore offer another illustration of the ways in which the press mediates or ‘filters’ our experience of reality, and because the typewriter enables such interventions, allowing writers to compose texts in a standardized font that is easily reproducible, these collages offer a perfect illustration of McLuhan’s claim that ‘[t]he typewriter fuses composition and publication’ (1964b:228).

A similar kind of typesetting experiment can be seen in Burroughs’s film scripts, such as The Last Words of Dutch Schultz (1975), where he uses multiple columns to describe the sound and image tracks of a non-existent film about the gangster Dutch Schultz. By using Hollywood terminology, as well as employing various gangster film clichés, Burroughs effectively imitates the language and style of Hollywood films. The script also includes photographs from Hollywood films and press clippings concerning the actual Schultz, thus blurring the boundaries between fictional and documentary sources and exposing the ways in which the mass media, including both the film industry and the world press, effectively determines and controls people’s perceptions of reality. The script also performs a similar kind of intervention as his earlier typesetting experiments by employing separate columns for sounds and images. In other words, rather than following the strict format of traditional screenplays, Burroughs’s script simultaneously represents both an imitation and a subversion of yet another institutional form of textual production. The sound and image columns are also reminiscent of the ‘Exhibition’ in The Ticket that Exploded, which isolates and manipulates sound and image tracks in order to create random and striking juxtapositions that draw the spectator’s attention to the constructed nature of the media itself (TE 62–8).

The purpose of these interventions, therefore, is ultimately not to participate in the mass media but rather to subvert and dismantle its methods of presenting information. This is most apparent in Burroughs’s three-column cut-ups, in which three separate columns of text are combined on the same page. Although these cut-ups resemble Burroughs’s newspaper and magazine collages, the purpose of the juxtaposed columns is ultimately to subvert the newspaper format, not to replicate it. This method is clearly based on the theoretical tape recorder experiment Burroughs describes in The Ticket that Exploded, where he suggests recording various sides of an argument onto three tape recorders and allowing them to argue with each other (TE 163). The purpose of this experiment is to externalize language and remove it from the body, while at the same time deflating the power of words through their simultaneous and overlapping transmission in a nonsensical cacophony of sound. Like the three tape recorders, the three columns of text also produce multiple, competing voices simultaneously vying for the reader’s attention, and the reader has to choose whether to read the columns in sequence from beginning to end, to read the individual pages in sequence, jumping between columns at the bottom of each page, or to read across the page from left to right, jumping between columns on every line. These compositions thus represent a radically new kind of information space—a proto-hypertext—in which the role of the author is displaced and linear structure is disrupted. In some of these compositions, such as ‘Who Is the Third That Walks Beside You’, Burroughs even decenters his own authority by combining found documents with excerpts from his novels (BF 50–2). He effectively makes these already cut-up passages even more disorienting by removing them from their original context, resplicing them into new arrangements and setting them in juxtaposition to one another. As if to emphasize the purpose behind this procedure, he also includes a passage from The Ticket that Exploded, in which he encourages the reader to ‘disinterest yourself in my words. Disinterest yourself in anybody’s words, In the beginning was the word and the word was bullshit’ [sic] (BF 51).

Burroughs’s grids represent yet another method of manipulating written information. The grids follow the same logic as Burroughs’s three-column cut-ups, although the vertical columns are also divided horizontally into a series of boxes, thus multiplying the number of potential links the reader is able to make between the blocks of text. Burroughs employs this method in many of his collages, such as To Be Read Every Which Way, in which he divides four vertical columns of text into nine rows, thus creating 36 boxes of text which can be read in any order (Sobieszek 1996:27). Much of this work was compiled for the original edition of The Third Mind, which was never published; however, in his essay ‘Formats: The Grid’, Burroughs describes this method as ‘an experiment in machine writing that anyone can do on his own typewriter’ (Burroughs 1964:27), and he illustrates the process using material taken from reviews of Naked Lunch:

I selected mostly unfavorable criticism with a special attention to meaningless machine-turned phrases such as ‘irrelevant honesty of hysteria,’ ‘the pocked dishonored flesh,’ ‘ironically the format is banal,’ etc. Then ruled off a grid (Grid I) and wove the prose into it like start a sentence from J. Wain in square 1, continue in squares 3, 5 and 7. Now a sentence from Toynbee started in squares 2, 4 and 6. The reading of the grid back to straight prose can be done say one across and one down. Of course there are many numbers of ways in which the grid can be read off. (Burroughs 1964:27)

Like the ‘fold-in’ method, therefore, the grid illustrates the displacement of the author as the controlling consciousness of the text; other than choosing which texts to use, the author has little to no control over the ultimate arrangement. Burroughs adds, for example, that ‘I found the material fell into dialogue form and seemed to contain some quite remarkable prose which I can enthuse over without immodesty since it contains no words of my own other than such quotations from my work as the critics themselves had selected’ (1964:27). Burroughs also notes that these textual ‘units are square for convenience on the typewriter’, but that this grid represents ‘only one of many possible grids […] No doubt the mathematically inclined could progress from plane to solid geometry and put prose through spheres and cubes and hexagons’ (1964:27). Like his three-column cut-ups, therefore, the grids also represent a kind of proto-hypertext, where the number of possible pathways and links between blocks of text are multiplied even further and the potential number of mathematical permutations seems virtually limitless. The grids are thus a logical extension of the auditory space created by the ‘fold-in’ method, and they seem to resemble Oulipian writing experiments, such as Raymond Queneau’s Cent Mille Millard de Poemes, a sonnet containing 10 possible choices for each of the 14 lines, thus comprising 1014 potential poems.

WRITING MACHINES AND THE GLOBAL VILLAGE

Burroughs’s writing machines not only illustrate the manipulation and subversion of information as a way of dismantling hierarchies of control, but they also illustrate the impact of media technologies on national identities and global borders by revealing the ways in which the electric media environment also reconfigures space and time. The revolutionary potential of the ‘fold-in’ method is even more pronounced in The Soft Machine, for example, because the act of shifting between source texts is played out within the narrative as shifts across space and time. ‘The Mayan Caper’ chapter opens with an astounding claim: ‘I have just returned from a thousandyear time trip and I am here to tell you […] how such time trips are made’ (SM 81). The narrator then offers a description of the procedure, which begins ‘in the morgue with old newspapers, folding in today with yesterday and typing out composites’ (SM 81). In other words, the ‘fold-in’ method is itself a means of time travel, because ‘when I fold today’s paper in with yesterday’s paper and arrange the pictures to form a time section montage, I am literally moving back to yesterday’ (SM 82). The narrator is then able to overthrow the Mayan control machine by employing the ‘fold-in’ method on the sacred codices and calendars. By once again altering the time sequence, the priests’ ‘order to burn [the fields] came late, and a year’s crop was lost’ (SM 92). Soon after, the narrator leads the people in a rebellion against the priests: ‘Cut word lines […] Smash the control machine—Burn the books—Kill the priests—Kill! Kill! Kill!’ (SM 92–3). This scene is perhaps the clearest illustration of Burroughs’s notion that the electric media environment allows for the spread of cultural revolution worldwide, as media technologies like the newspaper enable information to be conveyed rapidly across space and time, regardless of national borders, thus emphasizing group awareness over individual experience and global interdependence over national divisions.

Because the borders between the blocks of text in Burroughs’s grids are so fluid, they also seem to function as a corollary to the spatial architecture of the transnational ‘Interzone’ in Naked Lunch. This ‘Composite City’ is described as a vast ‘hive’ of rooms populated by people of every conceivable nation and race (NL 96). Because these inhabitants have clearly been uprooted from their ‘discrete localities’ and placed in a labyrinthine space, which appears completely removed from space and time, Interzone would appear to be the most perfect illustration of Tomlinson’s notion of the deterritorializing effect of media technologies. Burroughs also describes Interzone as ‘a single, vast building’, whose ‘rooms are made of a plastic cement that bulges to accommodate people, but when too many crowd into one room there is a soft plop and someone squeezes through the wall right into the next house’ (NL 162). Interzone therefore represents a kind of virtual grid, in which people are converted into units of information that pass freely across barriers without resistance. The transfer of bodies through walls thus serves as a metaphor for the structure of the text itself, which contains rapid shifts and jumps that allow characters to travel inexplicably across space and time. These shifts are largely due to the method with which the book was originally written. Burroughs wrote the sections in no particular order, and the final version of the novel was ultimately determined by the order in which the pages were sent to the compositor. This process once again reflects the structure of hypertexts in that linearity is absent and the reader is free to choose multiple pathways: ‘You can cut into Naked Lunch at any intersection point’ (NL 203). Burroughs also emphasizes that the beginning and the ending of the novel are artificial constructs and that the novel includes ‘many prefaces’ (NL 203). The fact that the virtual information space of the text is essentially a product of writing machines is made even more explicit when Burroughs describes these shifts as the effect of ‘a broken typewriter’ (NL 86).

This rapidly shifting and disorienting atmosphere also reflects the drug-induced state in which Burroughs began writing the novel. His description of the city, for example, quickly merges with his description of the effects of yagé, which is further reflected in his apparently random and disconnected prose style: ‘Images fall slow and silent like snow […] everything is free to enter or to go out […] Everything stirs with a writhing furtive life.…The room is Near East, Negro, South Pacific, in some familiar place I cannot locate.… Yage is space-time travel’ (NL 99). This passage would seem to support McLuhan’s claim that Burroughs’s drug use represents a ‘strategy of by-passing the new electric environment by becoming an environment oneself’ (1964a:517), an interpretation which Burroughs rejects in his 1965 Paris Reviewinterview: ‘No, junk narrows consciousness. The only benefit to me as a writer […] came to me after I went off it’ (Knickerbocker 1965:23). Subsequent critics, such as Eric Mottram, have attempted to reconcile this disagreement by turning the discussion away from the effects of media on mental states and arguing instead that the essential similarity between Burroughs and McLuhan is their mutual interest in the globalizing power of electric media: ‘Burroughs corrects McLuhan’s opinion that he meant that heroin was needed to turn the body into an environment […] But his books are global in the sense that they envisage a mobile environmental sense of the network of interconnecting power, with the purpose of understanding and then attacking it’ (Mottram 1971:100). This disagreement can be resolved, however, by considering the difference between heroin, which ‘narrows consciousness’, and yagé, which eliminates individualism and effects a return to tribal ways of thinking. At the same time that Burroughs rejects McLuhan’s claim, for example, he also adds that he wants ‘to see more of what’s out there, to look outside, to achieve as far as possible a complete awareness of surroundings’ (Knickerbocker 1965:23). These are precisely the reasons why Burroughs sought yagé, and it is only under the influence of this drug that he effectively reproduces the conditions of the electric media environment within his own body.

The auditory space of the text therefore parallels the physical geography of Interzone, and any sense of the individual—including any sense of the author as the controlling consciousness of the text—dissolves in a larger awareness of human unity. Such a reading might imply that Interzone illustrates McLuhan’s notion of a ‘global village’, which enables a greater degree of equality between nations. The narrator adds, however, that Interzone is also ‘a vast silent market’, whose primary purpose is to conduct business transactions (NL 96). Interzone therefore not only represents a deterritorialized space marked by fluid borders and rapid transfers, but it also illustrates the essential link between cultural and economic exchange because it is impossible to separate the sharing of cultural ideas and differences from the exchange of goods and services. According to Fredric Jameson, for example, the term ‘globalization’ itself refers to the combined effect of both new information technologies and world markets, and it ‘affirms a gradual de-differentiation of these levels, the economic itself gradually becoming cultural, all the while the cultural gradually becomes economic’ (1998:70). McLuhan was also aware that the effects of electric media technologies would be far more devastating on the Third World than on Western culture: ‘In the case of the First World […] electronic information dims down nationalism and private identities, whereas in its encounter with the Third World of India, China, and Africa, the new electric information environment has the effect of depriving these people of their group identities’ (McLuhan and Powers 1989:165). Because Interzone illustrates both the economic and cultural effects of globalization, it is perhaps easy to understand why Interzone does not represent a more harmonious and egalitarian ‘global village’. The loss of group identities and economic stability, and the constant presence of European colonials, only seem to heighten the level of corruption and inefficiency already present in the city, such as the ‘drunken cop’ who registers new arrivals ‘in a vast public lavatory’, where the ‘data taken down is put on pegs to be used as toilet paper’ (NL 98). Business itself is also represented as an essentially hopeless process, in which useless products are endlessly waiting to be passed through customs, and embassies direct all inquiries to the ‘We Don’t Want To Hear About It Department’ (NL 163).

Like the ‘global village’, therefore, Interzone represents a virtual or deterritorialized space in which people of every imaginable nationality and race are able to meet and exchange information. But unlike the ‘global village’, Interzone is a labyrinth of both communication and economic exchange, which ultimately subdues and disempowers its inhabitants. The key to liberating the global space of the electric media environment, according to Burroughs, is to subvert and manipulate the media technologies themselves, thus drawing the hypnotized masses out of their waking dream and making them more aware of the degree to which media technologies condition their perceptions of reality. In Naked Lunch, for example, Burroughs states that the ultimate purpose of conventional narrative transitions is ‘to spare The Reader stress of sudden space shifts and keep him Gentle’ (NL 197). By manipulating the linear function of his own writing machines, Burroughs attempts to reject these conventions and transform the gentle reader into a potential revolutionary, who would no longer be passive and detached but rather aware and involved.

CONCLUSION

Burroughs most clearly represents the manipulation and subversion of electric media technologies through his own experimental methods of constructing texts. Burroughs also repeatedly represents writing machines within his work to illustrate the effects of information technologies on subjectivity, as well as their potential use for either positive or negative ends—as control machines or weapons of resistance. Burroughs similarly depicts the global impact of the electric media environment by illustrating the ways in which writing machines are capable of spreading either cultural revolution or cultural imperialism, depending on whether or not people are capable of appropriating and manipulating them. The texts which I have focused on in this chapter, which include examples of Burroughs’s work from the 1950s to the early 1970s, can therefore be seen as exposing and subverting the influence of writing machines on the material conditions of their own production in order to provide a model of technological reappropriation that could potentially be extended on a global scale. Burroughs’s work thus retains an empowering notion of human agency while also complicating the divisions between self and other.

REFERENCES

Bockris, V. (1981) With William Burroughs: A Report from the Bunker, rev. edition (New York: St. Martin’s Griffin, 1996).

Bukatman, S. (1993) ‘Gibson’s Typewriter’, South Atlantic Quarterly 92(4), pp. 627–45. Burroughs, William S. (1964) ‘Formats: The Grid’, Insect Trust Gazette, 1, p. 27. —(1975) The Last Words of Dutch Schultz: A Fiction in the Form of a Film Script (New York: Viking), pp. 37–46. Grauerholz, J. (1998) ‘A Hard-Boiled Reporter’, IN WV pp. 37–46. Hayles, N. K. (1999) How We Became Posthuman: Virtual Bodies in Cybernetics, Literature, and Informatics (Chicago: University of Chicago Press). Jameson, F. (1998) ‘Notes on Globalization as a Philosophical Issue’, IN Jameson, F., and Miyoshi, M. eds, The Cultures of Globalization (Durham, NC: Duke University Press), pp. 54–77. Kittler, F. (1990) Discourse Networks 1800/1900, Cullens, C., and Metteer, M. trans. (Stanford: Stanford University Press). —(1999) Gramophone, Film, Typewriter, Winthrop-Young, G., and Wutz, M. trans. (Stanford: Stanford University Press). Knickerbocker, C. (1965) ‘William Burroughs: An Interview’, Paris Review 35, pp. 13–49. McLuhan, M. (1962) The Gutenberg Galaxy: The Making of Typographic Man (Toronto: University of Toronto Press). — (1963) ‘The Agenbite of Outwit’, Location 1(1), 41–4. — (1964a) ‘Notes on Burroughs’, The Nation 28 December 1964, pp. 517–19. — (1964b) Understanding Media: The Extensions of Man (New York: McGraw-Hill) — (1963) ‘The Agenbite of Outwit’, Location 1(1), 41–4. —— (1964a) ‘Notes on Burroughs’, The Nation 28 December 1964, pp. 517–19. — (1964b) Understanding Media: The Extensions of Man (New York: McGraw-Hill) Mottram, E. (1971) William Burroughs: The Algebra of Need (Buffalo, NY: Intrepid). Sobieszek, R. (1996) Ports of Entry: William S. Burroughs and the Arts (Los Angeles: Los Angeles County Museum of Art/Thames & Hudson). Tanner, T. (1971) City of Words: American Fiction 1950–70 (London: Jonathan Cape). Tomlinson, J. (1999) Globalization and Culture (Chicago: University of Chicago Press)

Retaking the Universe (William S.Burroughs in the Age of Globalization)

Part 2: Writing, Sign, Instrument: Language and Technology/Burroughs’s Writing Machines/Edited by Davis Schneiderman and Philip Walsh First published 2004 by Pluto Press 345 Archway Road, London N6 5AA 22883 Quicksilver Drive, Sterling, VA 20166–2012, USA www.plutobooks.com

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Steven Craig Hickman - The Intelligence of Capital: The Collapse of Politics in Contemporary Society

Steven Craig Hickman - Hyperstition: Technorevisionism – Influencing, Modifying and Updating Reality

Archives

April 2020

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed