|

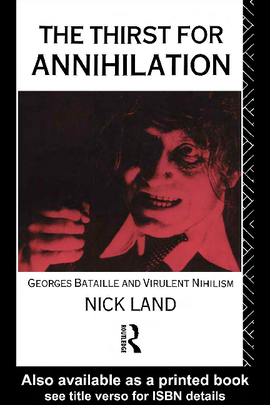

by Nick Land This is the freedom of the void which rises to a passion and takes shape in the world; while still remaining theoretical, it takes shape in the Hindu fanaticism of pure contemplation, but when it turns to actual practice, it takes shape in religion and politics alike as the fanaticism of destruction— the destruction of the whole subsisting social order—as the elimination of individuals who are objects of suspicion to any social order, and the annihilation of any organization which tries to rise anew from the ruins [H VII]. the republic being permanently menaced from the outside by the despots surrounding it, the means to its preservation cannot be imagined as moral means, for the republic will preserve itself only by war, and nothing is less moral than war. I ask how one will be able to demonstrate that in a state rendered immoral by its obligations, it is essential that the individual be moral? I will go further: it is a very good thing he is not. The Greek lawgivers perfectly appreciated the capital necessity of corrupting the member citizens in order that, their moral dissolution coming into conflict with the establishment and its values, there would result the insurrection that is always indispensible to a political system of perfect happiness which, like republican government, must necessarily excite the hatred and envy of all its foreign neighbours. Insurrection, thought these sage legislators, is not at all a moral condition; however, it has got to be a republic’s permanent condition. Hence it would be no less absurd than dangerous to require that those who are to ensure the perpetual immoral subversion of the established order themselves be moral beings: for the state of a moral man is one of tranquillity and peace, the state of an immoral man is one of perpetual unrest that pushes him to, and identifies him with, the necessary insurrection in which the republican must always keep the government of which he is a member [S III 498]. We have no true pleasure except in expending uselessly, as if a wound opens in us [X 170]. the most unavowable aspects of our pleasures connect us the most solidly [IV 218]. It has often been suggested—not least by Sartre—that Bataille replaces dialectic and revolution with the paralysed revolt of transgression. It is transgression that opens the way to tragic communication, the exultation in the utter immolation of order that consummates and ruins humanity in a sacrifice without limits. Bataille is a philosopher not of indifference, but of evil, of an evil that will always be the name for those processes that flagrantly violate all human utility, all accumulative reason, all stability and all sense. He considers Nietzsche to have amply demonstrated that the criteria of the good: selfidentity, permanence, benevolence, and transcendent individuality, are ultimately rooted in the preservative impulses of a peculiarly sordid, inert, and cowardly species of animals. Despite his pseudo-sovereignty, the Occidental God—as the guarantor of the good—has always been the ideal instrument of human reactivity, the numbingly antiexperimental principle of utilitarian calculus. To defy God, in a celebration of evil, is to threaten mankind with adventures that they have been determined to outlaw. The Kantian cultural revolution is associated with a deepened usage of juridical discourse in philosophy. Transcendental philosophy equates knowing with legislation, displacing the previously dominant axis of argumentation—extended between scepticism and belief—with one organized in terms of legitimacy and illegitimacy. The sense of logic, for example, undergoes a massive—if largely subterranean—shift; from evident truth to necessary rule. The metaphysical errors which Kant critiques are formally described as crimes, and more specifically, as violations of rights. The subject is divided into faculties, with strictly demarcated domains of legitimate sovereignty, beyond which their exercise is a transgression. Most important to Kant are the reciprocal injustices of reason and understanding, with his First Critique detailing the trespasses of reason upon the understanding, or theory, and his Second Critique defending reason against theoretical incursions into its proper domain; that of moral legislation. The lower faculties of sensation, and, to a lesser extent, imagination, are of more indirect concern, since they are branded as incorrigible reprobates; corrupted by their insinuation into the swamp of the body. Kant initiated the modern tradition of insidious theism by shielding God from theoretical investigation, whilst maintaining the moral necessity of his existence. God was exiled into a space of pure practical reason, simultaneously protected against intellectual transgression and underwriting moral law. In his Critique of Judgement Kant describes the moral impossibility of a world without God, and the fate of one attempting to live according to it, in the following terms: Deceit, violence, and envy will always be rife around him, although he himself is honest, peaceable, and benevolent; and the other righteous men he meets in the world, no matter how deserving they may be of happiness, will be subjected by nature, which takes no heed of such deserts, to all the evils of want, disease, and untimely death, just as are the other animals of the earth. And so it will continue to be until one wide grave engulfs them all—just and unjust, there is no distinction in the grave—and hurls them back into the abyss of the aimless chaos of matter from which they were taken—they that were able to believe themselves the final end of creation [K X 415–16]. This passage might be from Sade’s Justine: the Misfortunes of Virtue, reminding us that the age of Kant is tangled with that of Sade, a writer who explored the exacerbation of transgression, rather than its juridical resolution. Where Kant consolidated the modern pact between philosophy and the state, Sade fused literature with crime in the dungeons of both old and new regimes. Sade insisted upon reasoning about God repeating original sin, but even after obliterating him with a blizzard of theoretical discourse his hunger for atheological aggression remained insatiable, Sade does not seek to negotiate with God or the state, but to ceaselessly resist their possibility. Accordingly, his political pamphlets do not appeal for improved institutions, but only for the restless vigilance of armed masses in the streets. ‘Abstract negation’ or ‘negative freedom’ are Hegel’s expressions for this sterilizing resistance which erases the position of the subject. It could equally be described as real death. Bataille’s engagement with Sade is prolonged and intense, but also sporadic, consisting of articles and essays which never reach the pitch of intimacy characterizing Sur Nietzsche. After Nietzsche, however, it is Sade who comes closest to such an intimacy, and—like Nietzsche—accompanies Bataille throughout the entire length of his textual voyage, with an intellectual solidarity so great that it touches upon a complete erasure of distinction. Sade plays an important role in luring Bataille’s discussion of eroticism into its abyssal (non)sense, because his writing is baked to charcoal in the sacred. No writer fathoms more profoundly the utter inutility of the erotic impulse, nor its sacrilegious and insurrectionary fury. ‘Sade consecrated interminable works to the affirmation of unacceptable values: according to him life is the search for pleasure, and pleasure is proportional to the destruction of life. In other words, life attains the highest degree of intensity in a monstrous negation of its principle’ [X 179]. The orgies, massacres, and blasphemies of the Sadean text knit almost seamlessly onto Bataille’s obsession with an intolerable sacrificial wastage vomited into the suppurating cavity of the divine. Bataille finds in these texts ‘the excessive negation of the principle upon which life rests’ [X 168], a pitch of voluptuary intensity at which eroticism passes unreservedly into the sacred. Compared to the Sade-interpretations of Blanchot, for instance, despite complex affinities and inter-textual communications, there is a ravine as great as any that could be imagined; an incommensurability of thought insinuated into a common and inevitable vocabulary. ‘Negation’, ‘crime’, ‘atheism’, ‘revolt’, are words that Bataille associates with a heterogeneity so repugnant to elevated thought that its repression must be presupposed in the origination of any possible speculation, whereas for Blanchot these are words that belong to reason itself, at least, from the moment that it is permitted to find itself in the solitude of literature. It is only our inertia and our hypocrisy—as Blanchot suggests with an insidious power—that protect us from the latent fury of reason. Unlike Blanchot, Bataille does not emphasize the ruthless consistency of enlightenment rationalism in Sade’s writings, even though he acknowledges that Sade seems ‘to have been the most consequential representative of XVIIIth century French materialism’ [I 337]. ‘By definition, excess is external to reason’ [X 168], he remarks in one discussion of Sade, and it is an incitement to criminality, rather than an exultant rationality that he detects in passages such as this: atheism is the one system of all those prone to reason. As we gradually proceeded to our enlightenment, we came more and more to feel that, motion being inherent in matter, the prime mover existed only as an illusion, and that all that exists having to be in motion, the motor was useless; we sensed that this chimerical divinity, prudently invented by the earliest legislators, was, in their hands, simply one more means to enthrall us, and that, reserving unto themselves the right to make the phantom speak, they knew very well how to get him to say nothing but what would shore up the preposterous laws whereby they declared they served us [S III 482]. Either believe in God and adore him, or disbelieve and demobilize, for it is as senseless to rage against omnipotence as inexistence. Thus it is that Sade’s opponents take the two strands of his defiance to be mutually contradicting, to cancel each other, and—once aufhebt—expressing either a futile rage flung into the void, or a desperate plea for reconciliation. ‘Blasphemy is never logical. If an omnipotent God exists, the blasphemer can only be damaging himself by insulting him; if he does not exist, there is no one there to insult’, writes Hayman [Hay 31]. After all, how can one revolt against a fiction? It is perhaps a symptom of fixation or regression, an unresolved infantilism in any case, for affect to be detached so completely from an acknowledged reality. In a world divided between theistic enthusiasts and secularist depressives there is little patience for the atheist who nurtures a passionate hatred for God. The mixture of naturalism and blasphemy that characterizes the Sadean text occupies the space of our blindness, to which Bataille’s writings are not unreasonably assimilated. If there is contradiction here it is one that is coextensive with the unconscious; the consequence of a revolt incommensurate with the ontological weight of its object. That God has wrought such loathesomeness without even having existed only exacerbates the hatred pitched against him. An atheism that does not hunger for God’s blood is an inanity, and the anaemic feebleness of secular rationalism has so little appeal that it approximates to an argument for his existence. What is suggested by the Sadean furore is that anyone who does not exult at the thought of driving nails through the limbs of the Nazarene is something less than an atheist; merely a disappointed slave. Amongst the diseases Bataille shares with Nietzsche is the insistence that the death of God is not an epistemic conviction, but a crime. It is no less worthy of cathedrals than the tyrant it abolished, and whose grave it continues to desecrate. Indeed, such new cathedrals are inextricable from the unholy festivities of desecration which resound through them, as the texts of Sade, Nietzsche, and Bataille themselves illustrate. The illimitable criminality driving Bataille’s writing’s provokes no hint of repentence within it, but that does not make him a pagan, which is to say juridically: unfit to plead. Lacking the slightest interest in justification, innocence is not an aspiration he nourishes. He is closer to Satan than to Pan, propelled by a defiant culpability. Bataille is altogether too morbid to be a pagan, and yet, despite what is in part a reactive relation to Christianity, the thought of necessary crime is an interpretation of the tragic, and of hubris. Tragic fate is the necessity that the forbidden happen, and happen as the forbidden. Quoting what he takes to be a latent popular maxim, Bataille writes that ‘the prohibition is there to be violated’ [X 67]. He associates this subterranean collective insight with an ‘indifference to logic’ [X 67] at the root of social regulation, since ‘[t]he violation committed is not of a nature to suppress the possibility and the sense of the emotion opposed to it: it is even the justification and the source’ [X 67]. One of his formulae for this effective paradox is the ‘viola t [ion of] prohibition …according to a rule’ [X 75]. Such a violation is not so much provoked by prohibition, as it is compelled by an inexorable process to which prohibition is a response. This thought is commonly expressed within his writings in terms of the economic inevitability of evil, and also, occasionally, as the eruption of transgression. As an overt theme, ‘transgression’ is nothing like as dominant within Bataille’s writings as is often suggested, and it is only with extraordinary arbitrariness that he can be described as a ‘philosopher of transgression’. If it were not for the sustained discussion to be found in Eroticism it is unlikely that this term would have come to be read as anything more than the marginal elaboration of a more basic problem (that of expenditure, consumption, or sacrifice). Nevertheless, criminal variations analagous to transgression are prolifically distributed throughout his writings, and lend themselves with apparent ease to a measure of formulation. In a broadly Nietzschean fashion, Bataille understands law as the imperative to the preservation of discrete being. Law summarizes conditions of existence, and shares its arbitrariness with the survival of the human race. The servility of a legal existence is that of an unconditional one (of existence for its own sake); involving the submission of consumption to its reproduction, and eventually to its complete normative suppression within an obsessional productivism. The word Bataille usually employs to mark the preserve of law is ‘discontinuity’, which is broadly synonymous with ‘transcendence’; Bataille’s thought of discontinuity is more intricate than his fluent deployment of the word might indicate. It is the condition for transcendent illusion or ideality, and precisely for this reason it cannot be grasped by a transcendent apparatus, by the inter-knitted series of conceptions involving negation, logical distinction, simple disjunction, essential difference, etc. Discontinuity is not ontologically grounded (in the fashion of a Leibnizean monad for instance), but positively fabricated in the same process that amasses resources for its disposal. Accumulation does not presuppose a subject or individual, but rather founds one. This is because any possible self—or relative isolation—is only ever precipitated as a precarious digression within a general economy, perpetually renegotiated across the scale of energy flows. The relative autonomy of the organism is not an ontological given but a material achievement which—even at its apex—remains quite incommensurable with the notion of an individual soul or personality. It is in large part because death attests so strongly to this fact that theology has monotonously demanded its systematic effacement. Because isolation is—in an abnormal sense—‘quantitative’, quantity cannot be conceived arithmetically on the basis of discretion. Base, general, or solar economics— which are amongst Bataille’s names for economics at the level of emergent discontinuities—cannot be organized by any prior conceptual matrix. The distinctions between quantity/quality, degree/kind, analogue/ digital, etc., which typically manage economic thought, are all dependent upon the prior acceptance of discontinuity or derivative articulation. It is obvious that the economics or energetics which Bataille associates with base cosmology cannot be identified with any kind of physicalistic theory, since the logical and mathematical concepts underlying any such theory are devastated by the radical interrogation of simple difference. With the operation of a sufficiently delicate materialist apparatus general economy can in large measure be thought, but in the end its fragmentary and ironic character stems from a delirial genesis in the violation of articulate lucidity. The solar source of all terrestrial resources commits them to an abysmal generosity, which Bataille calls ‘glory’. This is perhaps best understood as a contagious profligacy, according to which all inhibition, accumulation, and reservation is destined to fail. The infrastructure of the terrestrial process inheres in the obstructive character of the earth, in its mere bulk as a momentary arrest of solar energy flow, which lends itself to hypostatization. When the silting-up of energy upon the surface of the planet is interpreted by its complex consequences as rigid utility, a productivist civilization is initiated, whose culture involves a history of ontology, and a moral order. Systemic limits to growth require that the inevitable re-commencement of the solar trajectory scorches jagged perforations through such civilizations. The resultant ruptures cannot be securely assimilated to a meta-social homeostatic mechanism, because they have an immoderate, epidemic tendency. Bataille writes of ‘the virulence of death’ [X 70]. Expenditure is irreducibly ruinous because it is not merely useless, but also contagious. Nothing is more infectious than the passion for collapse. Predominant amongst the incendiary and epidemic gashes which contravene the interests of mankind are eroticism, base religion, inutile criminality, and war. by the book: The Thirst for Annihilation/Chapter 3: Transgression by Nick Land

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Steven Craig Hickman - The Intelligence of Capital: The Collapse of Politics in Contemporary Society

Steven Craig Hickman - Hyperstition: Technorevisionism – Influencing, Modifying and Updating Reality

Archives

April 2020

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed