|

This article was originally delivered as ‘From a Tickle to an Inferno: The Theory of Jouissance in Psychoanalysis’ to the School of the Freudian Letter, Cyprus, May 2015.

We are at the Catholic University of Louvain in the early 1970s. The lecture Lacan is about to give is the only known recorded instance of his appearance in front of a public audience. He enters to applause, jokes with the crowd, and his performance thereafter is extremely theatrical. Later, the camera will capture some equally dramatic interventions from the audience.

When things quieten down Lacan recounts the story of a patient who, “a long time ago had a dream that the source of existence would spring from her forever more. An infinity of lives descending from her in an endless line.”

After a pause, the question he shouts at his audience, emphatically, is:

“Est-ce que vous pourriez supporter la vie que vous avez?”

– “Can you bear the life that you have?”

This is the essence of jouissance.

The life that Lacan talks about here is not our day-to-day lives, replete with the little dramas of our jobs, friends, and family relationships, but the excess of life commensurate with going beyond the pleasure principle. Life itself, as he describes it at one point, is simply an “apparatus of jouissance”.

loading...

Two Definitions of Jouissance. And What it ‘Feels Like’

Here are two definitions of jouissance as a way to orientate ourselves in this topic. We will come back to them in everything that follows:

1. Jouissance as an excess of life

2. Jouissance as an enjoyment beyond the pleasure principle.

As an ‘excess of life’ Lacan describes it in Seminar VII as a “superabundant vitality” (Seminar VII, 18th May 1960). It cannot be correlated to affect, or to an emotion.

As an enjoyment that goes beyond the pleasure principle he describes it in Seminar X, beautifully, as a “backhanded enjoyment”. (Seminar X, 23rd January 1963).

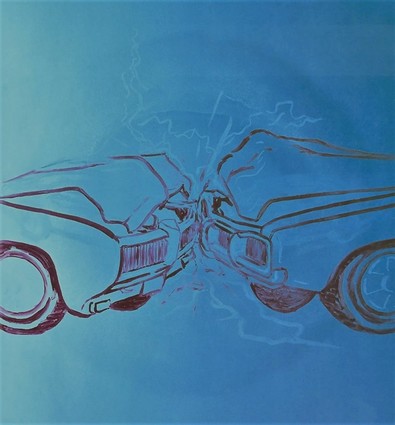

But in order to understand jouissance we have to understand what it ‘feels like’. Lacan expresses this in a sharp analogy in Seminar XVII: jouissance “Begins with a tickle and ends with blaze of petrol”. (Seminar XVII, p.72).

Finding the Idea of Jouissance in Freud

Jouissance is a Lacanian notion, but where can we find its heritage in Freud’s work? Let’s briefly retrace this in three stages:

1. Early Freud

We can start with the idea of the pleasure principle, foundational from Freud’s early writings. It is essentially an economic principle to limit a quanta of excitation and is therefore presented by Freud as a principle of constancy or inertia. The job of the pleasure principle is to regulate an increase or decrease of tension on a pleasure-unpleasure scale. This picture becomes more complex over time, up to the point of Instincts and their Vicissitudes (Triebe und Triebschicksale) in 1915, where he portrays a very complicated relation between pleasure and unpleasure (SE XIV, 121 and accompanying footnote).

From the outset the excitation, or energy of the drive, has a sexual colouring – libido. Freud sees this as its essential feature. But in the Écrits Lacan notes – in a beautiful expression – that this sexual colouring is nothing more than “the colour of emptiness, suspended in the light of a gap” (Écrits, 851-852). We will return to this idea.

Concurrent to the theoretical orientation Freud found in the pleasure principle is another idea from the early part of his work – that the symptom is a sexual act. In other words, that it represents an enjoyment, and a specifically sexual enjoyment.

This idea seems odd. A symptom is surely a problem, a suffering. The symptom goes beyond the pleasure principle and expresses itself in a disturbance, an unlust. But Freud saw that in the early examples his hysterical patients presented with, the complaint, the suffering, expresses itself in a paradoxical way, as if two wishes were simultaneously expressed. As if, he believed, the symptom was a compromise between two contradictory desires. Take the example of one hysterical patient: with one hand she pulls off the dress, with the other she puts it back on.

There is a wonderful example of this in the Rat Man case history. As he is describing the great obsessional thought which haunted his patient, Freud observed:

“His face took on a very strange, composite expression. I could only interpret it as one of horror at pleasure of his own of which he himself was unaware.” (SE X, 166-167).

2. Mid-Freud

Broadly speaking, in this period we have the development of libido theory in the context of the theory of narcissism from 1914, and the metapsychological papers of 1915 (SE XIV). Although Freud has used the term ‘libido’ since his first writings on anxiety in the late 1890s, by this point he increasingly emphasises the quantitative aspect of libido. When he comes to write the Group Psychology papers in 1921 (SE XVIII) he refers to a “quantitative magnitude” to libido. Freud’s project between these years is to develop an economic model in which ego-libido and object-libido are balanced against each other, with one rising as the other falls. However, the transformation of a quantitatively high degree of tension produced by the damming-up of the libido in the ego produces unpleasure. Its outlet is found in the attachment of libido to objects in the external world. As Freud summarises,

“A strong egoism is a protection against falling ill, but in the last resort we must begin to love in order not to fall ill, and we are bound to fall ill if, in consequence of frustration, we are unable to love”(SE XIV, 85).

Love is thereby the antidote to a kind of caustic narcissism that we can see as correlated to Lacan’s idea of jouissance. Lacan echoes Freud’s words in these terms in the early sixties when he says that “Only love allows jouissance to condescend to desire” (Seminar X, 13th March 1963).

3. Late Freud

In this period the two fundamental drives – Eros and the death drive – are introduced in place of the libido theory from the 1920 ‘Beyond the Pleasure Principle’ article onwards (SE XVIII). But from a Lacanian perspective we might be inclined to question the dualism this supposes. If jouissance is an experience of an excess of life, is the death drive not actually its opposite?

This idea seems to run counter to the whole of psychoanalytic metapsychology: what place for psychical conflict if the death drive is just an excess of life? It is as if Freudian theory has to maintain a place for a basic dualism animating internal conflict – whether that dualism is located between desire and defence; between the sexual and self-preservative instincts; between the ego, id, and super-ego; or between eros and the death drive. A conflictual dualism lies at the aetiology of the neuroses and animates their insistence. Indeed, it is from conflict that the symptom gains its strength, satisfying both sides of this conflict – for example, desire and defence – through a compromise formation. Ultimately Freud comes to believe that the struggle between different thoughts, desires, and fantasies is a reflection of a struggle between drives (SE XI, 213).

But at the end of his life, in ‘An Outline of Psychoanalysis’, things get a little trickier. It would seem initially that the dualism is maintained at the level of the id on one side, and the ego/super-ego on the other. The id does not care whether you live or die – it just cares about satisfaction; the ego/super-ego’s job is to moderate the ways by which this satisfaction is achieved, and thus it inherently limits satisfaction. This is how Freud expresses the difference in the opening lines of that paper:

“The power of the id expresses the true purpose of the individual organism’s life. This consists in the satisfaction of its innate needs. No such purpose as that of keeping itself alive or of protecting itself from dangers by means of anxiety can be attributed to the id. That is the task of the ego, whose business it also is to discover the most favourable and least perilous method of obtaining satisfaction, taking the external world into account” (SE XXIII, 148).

But what animates the id and the ego are instincts (drives), thereby taking the topography to another level:

“The forces which we assume to exist behind the tensions caused by the needs of the id are called instincts. After long hesitancies and vacillations we have decided to assume the existence of only two basic instincts, Eros and the destructive instinct. The contrast between the instincts of self-preservation and the preservation of the species, as well as the contrast between ego-love and object-love, fall within Eros.” (SE XXIII, 148).

So we have the Freudian dualism manifested across two levels, as it were:

Psychical agency-level – Id vs ego/super-ego

———————————————————-- Instinctual or drive level – Eros vs the death drive

But then Freud says something extraordinary:

“In biological functions the two basic instincts operate against each other or combine with each other. Thus, the act of eating is a destruction of the object with the final aim of incorporating it, and the sexual act is an act of aggression with the purpose of the most intimate union. This concurrent and mutually opposing action of the two basic instincts gives rise to the whole variegation of the phenomena of life” (SE XXIII, 149).

It would be too easy to think that Freud’s words here refer only to the pure satisfaction of basic biological functions, like eating to satisfy hunger, and that in the service of this need the two instincts combine. But if Freud’s work teaches us anything it is that Freud never subscribed to a definition of satisfaction as simply the sating of a need. Satisfaction is much more problematic for him. We have only to think about cases where an act that ostensibly satisfies a need exceeds that satisfaction, not just to the point of pleasure, but beyond it (in alcoholism, or binge-eating, to use Freud’s model of oral satisfaction above). The qualification Freud introduces in this passage complicates the picture greatly, as if we take him seriously it means that the dualism is really maintained only at the id vs ego/super-ego level; at the Eros vs death instinct level there is not necessarily any opposition – they can work against each other or with each other, he says. And this is why as Lacanians we can defend the thesis that the death drive can be manifested as an excess of life, correlate to the “superabundant vitality” in his definition of jouissance (Seminar VII, 18th May 1960).

What’s more, Freud says that we don’t even have to think of the death drive as an instinct of destruction: “So long as that instinct [the destructive instinct/drive] operates internally, as a death instinct, it remains silent; it only comes to our notice when it is diverted outwards as an instinct of destruction.” (SE XXIII, 150). This would help us understand why people who seem to be ruled by the death drive in cases of excessive jouissance are not violent or unpredictable. They can destroy themselves without destroying others.

Although people usually talk about the idea of the death drive as being a destructive or aggressive drive, Freud is careful to point out that “It is not a question of an antithesis between an optimistic and a pessimistic theory of life” (SE XIII, 242). The two fundamental drives are much more mixed together than any simplistic duality would suggest. And this is what is expressed in the concept of jouissance, which we can perhaps see Freud struggling to articulate in dualistic terms at the end of his life.

The Connections between Freud and Lacan

So where does Lacan stand in all of this? Where can we locate his concept of jouissance in the issues that Freud was battling with?

Lacan maintains his dialogue with Freud on these issues throughout his life, referencing the same conceptual vocabulary that Freud used to express the complicated relation between pleasure, unpleasure, and the drives when he is developing his notion of jouissance.

The pleasure principle is his starting point, and the long discussions with colleagues such as Mannoni, Valebrega, and Pontalis on the meaning of the term are a constant feature of the first part of Seminar II.

In (Seminar XIV) he gives what we can view as some substance to the notion of jouissance – what it actually ‘is’. There he tells his audience that jouissance is an ousia – a term borrowed from Aristotle’s book on the Categories – to mean an essence, related to being, at the level of the body ((Seminar XIV, 31st May 1967). And we know it in relation to the pleasure principle – it marks its traits but also marks its limits.

Lacan concurs with Freud’s definition of the pleasure principle as “a principle of the least tension, of the minimum tension that needs to be maintained for life to subsist”… but, he adds, that “jouissance overruns it” (Seminar XVII, p.45-46).

This quote from Seminar XVII in the late 1960s encapsulates the two definitions of jouissance that we started with: as an enjoyment beyond of the pleasure principle, and as an excess of life.

However Lacan’s idea of jouissance evolves over the course of his work, and in the early Seminars he does not use the term to describe this kind of malevolent enjoyment as he will come to do later. Instead in Seminars I, II and III we largely find references to the ‘jouissance’ of the master and slave, drawn from the influence Kojeve’s teaching of Hegel’s slave-master dialectic had on Lacan. Jouissance here is presented either as enjoyment or usufruct rights over the other. It is a jouissance linked to the body, but the body of the other realised in terms of the fruits of the other’s labour. It is not until Seminar VII that we find Lacan start to talk about jouissance as malevolent or evil (Seminar VII, 20th March 1960)

But we can see that even at this stage he is clear that jouissance is a phenomena at the level of the body. This idea continues throughout his work, and in Seminar XIV from 1967 we find Lacan stating not only that the body is the locus of jouissance, but that it is also the place where the Freudian ideas of Eros and Thanatos connect to each other, where they coincide.(Seminar XIV, 24th May 1967).

Jouissance and Desire

As an excess of enjoyment – an enjoyment that may not even be consciously experienced as such – jouissance is the most powerful counterforce to the work of a psychoanalysis. So what protects against or limits jouissance? The first answer is desire, and this is one of the ways that Lacan defines the latter. In the Écrits he writes that “Desire is a defense, a defence against going beyond a limit in jouissance” (Écrits,, 825). What this means is that rather than indulging a passion for jouissance, the metonymy of desire protects against going beyond a certain limit of pleasure, from going beyond what he calls in Seminar XIII the foyer brulant, or the burning hearth (Seminar XIII, , 23rd March 1966).

From early on in his work Lacan presents the symptom as a machine for ciphering unconscious desire, ensuring its repetition under a multitude of guises. Symptoms may perform different functions for different people, and perhaps a different function for the same person at different points in their life. They are not inherently a bad thing. But the symptom also carries with it a malignant jouissance. Insofar as the work of a psychoanalysis may involve supporting a symptom, or even helping to develop one that works better for a person, the criteria for a good symptom is one that will allow you to sustain your desire in its precariousness, rather than hooking you into a negative infinity around the object a (an idea we will explain below). In Seminar VI Lacan talks about these types of symptoms as “phantasmagoria”, a term which brings to mind a shifting series of illusions which are neither enjoyed too much nor too little. “Symptoms which are nevertheless so little satisfying in themselves”, as he describes them – not grossly unpleasurable, nor excessive, but simply “so little satisfying” (Seminar VI, 10th June 1959.) The task of a psychoanalysis then would be to enable the subject to walk the line between the tickle of the symptom and the inferno of jouissance (Seminar XVII, p.72).

Is Desire a Defence against Jouissance?

However, three caveats to this idea that desire is a defence against jouissance:

Firstly, that desire provides an insufficient satisfaction. As Lacan says in Seminar XI, “The subject will realise that his desire is merely a vain detour with the aim of catching the jouissance of the other” (Seminar XI, 183-184).

Secondly, desire can be a defence against jouissance but – as Lacan says about the hysteric in Seminar VI – jouissance can be a defence against desire. We can think about how Lacan understands the strategy of the hysteric in this regard. Speaking about hysterical subjects, Lacan makes the point that “here jouissance is precisely to prevent desire in situations that she herself constructs” (Seminar VI, 10th June 1959.) The hysteric does not necessarily want to stifle desire, but – as Lacan puts it here – to “prevent desire coming to term in order that she herself will remain what is at stake”, in other words, to keep desire going. Why does she want to keep it going? Because it is her being that is at stake, a being that exists to elicit the desire of the Other. This is a crucial clinical point therefore in being able to differentiate the ‘savage’ jouissance seen in some cases of psychosis from the ‘strategic’ jouissance which Lacan detects in hysterical subjects.

Thirdly, that desire cannot be an antidote to jouissance because it is not qualitatively equivalent to it. Jouissance is of a different nature to desire insofar as is at the level of the drive. In Seminar VII Lacan describes jouissance as “not purely and simply the satisfaction of a need but as the satisfaction of a drive” (Seminar VII, 209), whereas desire emerges from the split between this need and the demand for it to be satisfied, which is addressed to the Other. More simply, to explain this difference Lacan describes a sort of canyon, where “desire reveals certain ridges, a certain sticking point”, but in which jouissance “presents itself as buried at the centre of a field and has the characteristics of inaccessibility, obscurity and opacity” (Seminar VII, 209). Another more poetic formulation is given to this difference in the Écrits, where Lacan sums up the relation between desire and jouissance by describing the

“Misadventure of desire at the hedges of jouissance, watched out for by an evil god. This drama is not as accidental as it is believed to be. It is essential: for desire comes from the Other, and jouissance is located on the side of the Thing.” (Écrits, 853)

If we were looking for a dualism in Lacan to parallel what Freud is trying to construct perhaps we can find it between jouissance and desire.

Jouissance, Transgression, and Prohibition

So, if desire can’t put a satisfactory limit to jouissance, what can?

One of Freud’s ideas is that culture itself puts a break on our ability to obtain full jouissance, full enjoyment. The exemplar of this is the prohibition on incest. But Lacan contradicts this. In the Écrits he says that jouissance is usually forbidden to the subject, but not because of “bad societal arrangements”. He calls people who believe this “fools”. The Other is to blame, but as the Other does not exist we instead put the blame on ourselves and call it Original Sin (Écrits, 820). In Seminar IX Lacan is more explicit. The Other does not prohibit, he says. The Other – the Other as the Law – is a metaphor for prohibition rather than the cause of it. What looks like a prohibition from the Other is actually an impossibility of accessing the jouissance of the Thing (Seminar IX, 14th April 1962).

Lacan does say however is that jouissance is prohibited [interdite] for he who speaks, as such (Écrits, 821). What does he mean by this? It is not law or culture that makes jouissance forbidden to the subject, but rather a natural limit to pleasure itself. The law or culture “makes a barred subject out of an almost natural barrier”, he says in the Écrits.

“We must keep in mind that jouissance is prohibited [interdite] to whoever speaks, as such—or, put differently, it can only be said [dite] between the lines by whoever is a subject of the Law, since the Law is founded on that very prohibition

[….] But it is not the Law itself that bars the subject’s access to jouissance—it simply makes a barred subject out of an almost natural barrier. For it is pleasure that sets limits to jouissance, pleasure as what binds incoherent life together, until another prohibition – this one being unchallengeable — arises from the regulation that Freud discovered as the primary process and relevant law of pleasure.” (Écrits, 821).

The idea here is that we cannot go beyond a certain level of pleasure before we hit a wall of pain, the experience of jouissance. And what marks this limit is termed in psychoanalysis ‘castration’.

What is castration? Rather than being the removal of the genitals, Lacan sees it as a process by which a sacrifice is given a mark. This mark is a lack, something with a negative attached to it. The name Lacan gives to this is the phallus – the phallus not as the penis, but as the mark of a lack:

“… The sole indication of this jouissance in its infinitude, which brings with it the mark of its prohibition, and which requires a sacrifice in order to constitute this mark: the sacrifice implied in the same act as that of choosing its symbol, the phallus. This choice is allowed because the phallus—that is, the image of the penis—is negativized where it is situated in the specular image.” (Écrits, 822).

As the mark of a lack, the phallus allows us to enjoy only partially, with a ‘paltry’ jouissance. Lacan says that the phallus reduces jouissance to an auto-erotism (Écrits, 822). (Whether there is another kind of jouissance that is particular to women or to the mystic is something for speculation, but not something we’ll go into depth with here. For more on that point, see this article).

Nonetheless, Lacan hints that there is a way to use prohibition to augment this phallic, or paltry, jouissance. Prohibition, he believes, is the all-terrain vehicle that allows us to overcome some of the limits in jouissance – to stop our journey being just a series of well-trodden satisfactions.

“If the paths to jouissance have something in them that dies out, that tends to make them impassable, prohibition, if I may say so, becomes its all-terrain vehicle, its half-track truck, that gets it out of the circuitous routes that lead man back in a roundabout way toward the rut of a short and well-trodden satisfaction” (Seminar VII, 177).

But rather than trying to ‘maximise’ our paltry jouissance through transgression when we feel we are not enjoying enough, if prohibition comes from a natural barrier to pleasure rather than a Law imposed by the Other, then surely transgression itself is a sham? Enjoyment is not about transgression – if there’s really no law to transgress how can we do so? Lacan expresses this nicely in Seminar XVII:

“We don’t ever transgress. Sneaking around is not transgressing. Seeing a door half-open is not the same as going through it….”

And he then adds a crucial twist:

“There is no transgression here, but rather an irruption, a falling into the field, of something not unlike jouissance – a surplus” (Seminar XVII, p.20).

It is with this surplus that jouissance obtains a kind of ‘life of its own’. The excess invades or ‘irrupts’ as he puts it here, and leave us a surplus jouissance. Despite this ‘paltry’ phallic jouissance that we castrated subjects have to deal with, an excess of enjoyment – a plus de jouir – is generated in the place of castration. He calls this a compensation for a loss, and we can think of it as a kind of ‘plus of a minus’ – what he names in Seminar VII as “something that necessitates compensation… for what is initially a negative number” (Seminar VII, p.50).

But then Lacan issues a warning: you have to get rid of this surplus – “it is very urgent that one squander it”, he says in Seminar XVII – or you’re in big trouble:

“What’s disturbing is that if one pays in jouissance, then one has got it, and then, once one has got it it is very urgent that one squander it. If one does not squander it, there will be all sorts of consequences.” (Seminar XVII, p.20)

The term ‘squander’ here is an interesting one. Just as to squander money implies to frivolously spend it without care as to where it goes, so an ‘urgent squandering’ of jouissance implies the importance of finding an outlet without too much regard for how or where it gets expended. Any serviceable route to its evacuation is preferable to living with excess jouissance.

Jouissance and The Thing

This brings us to the idea of the Thing – das Ding – which Lacan goes on and on and on about in Seminar VII, from 1959-1960. It somewhat morphs into the theory of the object-cause of desire from then on, starting with the notion of agalma in Seminar VIII the following year, and then being more fully developed into object a around Seminars X and XI, and over the course of the rest of his work.

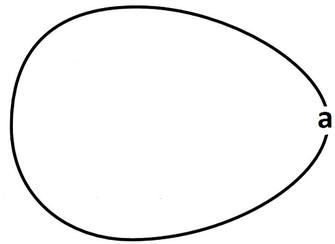

To explain the Thing and its relation to jouissance, here are two diagrams to illustrate the encounter with jouissance when we go beyond the pleasure principle.

This first diagram shows the path of the drive around the object, represented by a. The course of the drive is a kind of elliptical orbit around the object, rather than a straight line by which it would reach it. It is flung back around the object at the moment it is closest to it.

What this attempts to show is that the beyond of the pleasure principle is something internal to it. It is an internal flaw in the pleasure principle rather than something that intervenes from outside to limit pleasure (for example, the law or prohibition). As Slavoj Zizek writes,

“The space of the drive is as such a paradoxical, curved space: the object a is not a positive entity existing in space, it is ultimately nothing but a certain curvature of the space itself which causes us to make a bend precisely when we want to get directly at the object.” (Enjoy Your Symptom, p.56-57).

But even if this trajectory around the object produces displeasure (frustration, exhaustion) there is a kind of satisfaction found in this nonetheless. This is one way of understanding jouissance. Freud tells us that the drive is indifferent to its object, and can be satisfied without obtaining it (sublimation). It is not the object itself that is of importance, but what Joan Copjec describes as,

“a particular mode of attainment, an itinerary the drive must undertake in order to access its object or to gain satisfaction from some other object in its place. There is always pleasure in this detour – indeed this is what pleasure is, a movement rather than a possession, a process rather than an object” (Copjec, UMBR(a): Polemos, 2001, p.150).

The ultimate example of this is courtly love. The Lady in courtly love represents this kind of curved space towards the object. You cannot approach her directly, only in detours and ordeals. The Lady is less a substance than a semblance. You write a song about her rather than having sex with her. Any attempt to reach her is doomed to fail because her bodily materiality is really just a lure, a lure which is illustrated by the curvature of the drive: an attempt at a direct encounter, but one which cannot but miss.

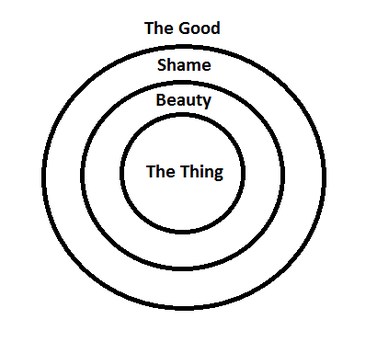

Here is the second diagram, based on Lacan’s ideas on the Thing – das Ding – in Seminar VII.

If we were to give a brief explanation of the Thing it would go something like this: the Thing is less a ‘thing’ than a point, though it is unreachable as both. We know the Thing only through our proximity to it, where the pursuit of a desired object in the service of the pleasure principle shades off into jouissance, up to the point that it implies what Lacan says – in no uncertain terms – is “the acceptance of death” (Seminar VII, p.189). Desire itself can be distinguished from jouissance. Lacan says in Seminar X that jouissance aims at the Thing (Seminar X, 23rd January 1963), whereas desire aims only at the promulgation of desire.

The first ring in the diagram is that of the good. In Seminar VII Lacan presents the good as the first barrier of protection against the jouissance of the Thing. This is what he believes Freud was getting at in Civilisation and its Discontents. Except that loving one’s neighbour neglects the fact that the neighbour’s jouissance poses a problem for your love (Seminar VII, p.187).

When we overcome the demands of the good we overcome a certain conception of ‘the good’ that Lacan wishes to distinguish from that of psychoanalysis. This might be the teleological good, the moral good, or simply the ‘good’ life of blameless bourgeois domesticity. Whatever, this entails the traversal of shame, the second ring.

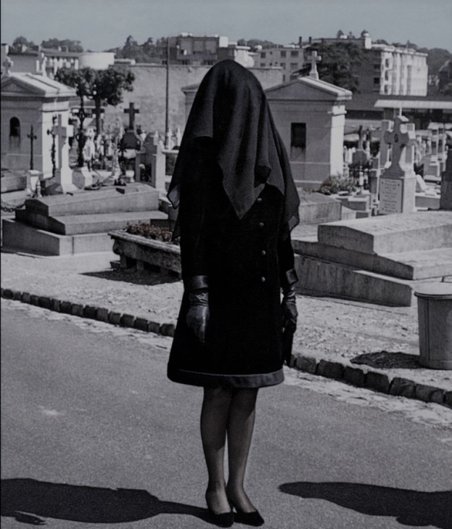

The last ring or barrier is that of beauty. And it is the most odd. In his discussion of Sophocles’ Antigone in Seminar VII Lacan is very interested in the few words that Antigone says at the graveside of her brother. Her desire to bury him is what Lacan seizes on as the exemplar of the ethical act. What she wants for her dead sibling is the minimal sign that the body is registered in the symbolic, and this is why his burial is so important for her. Indeed, burials are important for all of us. Anthropologically, rituals around the burial of the dead are one of the few common practices linking all human cultures throughout history.

Beauty as the Veil of Horror

In the moments before she is entombed alive Sophocles has the chorus talk about Antigone’s beauty. This is a term that is especially odd in this context and there is debate about whether Lacan translated it correctly. Nevertheless, his idea is that the ultimate barrier between death and life is the screen or veil of beauty which separates – is to final limit to – the horror of the Thing (Seminar VII, 248).

This idea of beauty as the final veil before the horror of death comes up again and again in Sade’s work. Lacan references him heavily in Seminar VII. Sadean victims rarely die – they endure all manner of painful tortures but retain their pristine beauty nonetheless. The image of the crucifixion shows this as well for Lacan (Seminar VII, 261-262). Throughout these examples runs the same thread: a barrier of beauty before we reach the horror of the Thing. This is the space between two deaths that Lacan talks about in Seminar VII.

There is a nice anecdote about the Velvet Underground singer Lou Reed that illustrates this idea of beauty veiling the horror of the Thing. For the purposes of hotel registers when on the road Reed would adopt the pseudonym Raymond Chandler. Asked what he liked about the noir genius of the detective story he replied, “Biting humor and succinctness”. When asked for an example he gave the line ‘That blonde is about as beautiful as a split lip.’

Sublimation as Raising the Object to the Dignity of the Thing

There is also a special role for sublimation in the proximity to the Thing. In Seminar VII Lacan says that we can’t ever reach the Thing, and so as a compensation for that inaccessibility we sublimate:

“We have at present reached that barrier beyond which the analytical Thing is to be found, the place where brakes are applied, where the inaccessibility of the object as object of jouissance is organised. It is in brief the place where the battlefield of our experience is situated… in order to compensate for that inaccessibility, all individual sublimation is projected beyond that barrier…. The last word of Freud’s thought, and especially that concerning the death drive, appears in the field of analytical thought as sublimation” (Seminar VII, 203).

Lacan’s famous definition of sublimation as raising the object to the dignity of the Thing has precisely this meaning. The Lady in courtly love, and ‘the ‘broad’ in Lou Reed’s anecdote, are examples of this.

The Burning Bush and the Madonna

When the veil of beauty is removed we arrive at the Thing. In the term ‘Thing’ we can hear the resonance of the Kantian thing-in-itself (Ding an sich, “thing-as-such” or “thing per se”). Lacan’s idea is that the Thing is brutal and raw in its immediacy; it cannot be substituted for or assimilated to anything else. As an example, he describes Moses’ encounter with the burning bush in the old testament:

“Moses the Midianite seems to pose a problem of his own – I would like to know whom or what he faced on Sinai and on Horeb. But after all, since he couldn’t bear the brilliance of the face who said to him “I am what I am” we will simply say at this point that the burning bush was Moses’ Thing, and leave it there.” (Seminar VII, p.174 – see also Seminar VII, p.180).

Another example of the immediacy of the Thing comes from the Dora case. Describing to Freud how she sat transfixed in front of the painting of the Madonna in a Dresden gallery, she cannot find the words to describe it except than as itself:

“When I asked her what had pleased her so much about the picture she could find no clear answer to make. At last she said: ‘The Madonna’.” (SE VII, 96).

Jouissance and Anxiety

The confrontation with the Thing provokes anxiety. Again and again in Seminar X Lacan talks about anxiety as the middle term between jouissance and desire.

Jouissance – Anxiety – Desire

What Lacan had to say about the relation between anxiety and desire in Seminar X is well-known. The confrontation with the Other’s desire is like being in front of a female praying mantis – you know that the female bites the head off her partner after sex; and you know you are wearing a mask; but you do not know whether it’s the mask of a male or female praying mantis (Seminar X, 14th November 1962). But what does he have to say about the relation of anxiety and jouissance?

Here we can return to the topic of castration. Lacan’s idea in Seminar X is that castration covers the anxiety presented by the actualisation of jouissance (Seminar X, 5th June 1963). Let’s look at this in relation to what one of his smartest followers, Piera Aulagnier, had to say about jouissance and sex.

Piera Aulagnier

Lacan gives her the floor for a session in Seminar IX in 1962. Aulagnier is interested in what difference there is between masturbation and sex. And the answer she proposes is that in sex both partners have to accept their castration. If either partner is focussed only on the partial object there is no recognition of theirs or the other’s subjectivity. This creates a situation analogous to the story of the preying mantis from Seminar X that we touched on above – you have no idea what you are for the other person. For Aulagnier, this generates anxiety, and so castration is necessary to avoid it (Seminar IX, 2nd May 1962).

But then Aulagnier says something brilliant about castration: rather than being the fear that the penis will be cut off, the real fear is that the penis will remain but that everything else will be cut off. This would make it impossible for the subject to be recognised as a subject which, as we have seen, is the most anxiety-provoking of experiences because you would not know what you are for the Other. We are back to the praying mantis.

loading...

Modalities of Jouissance

Although the experience of jouissance will be different for each subject, let’s conclude by looking at some of what Lacan has to say about the character of jouissance in different subjective structures.

Firstly, for the neurotic, the greatest fear is that he will be forced to sacrifice his castration to the jouissance of the Other (Écrits, 826). The neurotic not only believes very strongly in the Other, but believes the Other demands his castration so as to serve the Other’s enjoyment.

For the pervert, secondly, the situation is a little more complex. Taking the example of sadism, Lacan argues that rather than being the master of his object, the sadist actually serves his own master. We find again here the theme of alienation from one’s enjoyment that Lacan thought was so interesting in Kojeve’s work on Hegel’s slave-master dialectic. The sadist is simply the agent of the jouissance of the Other. “I will ask you to look at my article Kant avec Sade”, Lacan says in Seminar XI, “where you will see that the sadist himself occupies the place of the object, but without knowing it, to the benefit of another, for whose jouissance he exercises his action as sadistic pervert.” (Seminar XI, 185). The sadist’s partner does not matter as such, only insofar as it is what he believes the Other wants.

Aulagnier however goes further. She argues that the pervert obtains jouissance by identifying with an object that produces the jouissance of the phallus. But there are two crucial modifications in her argument compared to Lacan’s. Firstly, in her view this object is not the partner but a material object which is used to procure the jouissance of a phallus which is not the sadist’s own. We can think of all the iconography of sadism – whip, chains, and so forth – as examples of this object. Secondly, that the jouissance the sadist aims at is not for the Other as such, but for an anonymised phallus. Her remarks are worth quoting in full:

“The pervert neither has nor is the phallus: he is this ambiguous object which serves a desire which is not his: his jouissance is in this strange situation where the only identification possible to him is as an object which procures the Jouissance of a phallus, but he doesn’t know to whom this phallus belongs. One could say that the desire of the pervert is to respond to the demand of the phallus. To take a banal example I would say that in order for the Jouissance of the sadist to appear, another is pleasured by the fact that he the pervert makes himself into a whip. If I speak of phallic demand, which is a kind of play on words, it is because for the pervert the other exists only as the almost anonymous support of a phallus for whom the pervert performs his sacrificial rights. The perverse response is always a negation of the Other as subject. The perverse identification is always to this object which is the source of the jouissance for a phallus which is as powerful as it is phantasmatic.” (Piera Aulagnier’s presentation in Seminar IX, 2nd May 1962)

Thirdly, to take just one example of psychosis, we can look at the work done on autism by the Belgian clinic Le Courtil. This is something we have looked at before on this site in regards to topology but to summarise that article briefly in the context of jouissance, autistic subjects face being overwhelmed by a jouissance at the level of the body that they have great difficulty defending against. Why? The topological approach in psychoanalysis answers this in terms of weak separation axiom. In short, a difficulty dealing with certain kinds of spatial realities.

Finally, the inability to manage a jouissance in the body also manifests itself very forcefully in addiction. Rik Loose’s work here is key. He argues that the addict short-circuits castration to go straight to the object:

“ … Addiction can produce pleasures for the subject in a manner that is independent of the Other and […] can provide the illusion that there is a pleasure to be obtained that is not curtailed or limited by the social bond. This allows one to understand that some addictions function as a social “short-circuit” symptom and contains the desire to pursue a pleasure beyond normal pleasure. This is a form of addiction that tries to break away from the “cut” of castration, that is to say, it tries to regain what had to be given up, or was lost, as the result of castration”. (Loose, The Subject of Addiction: Psychoanalysis and the Administration of Enjoyment, p.69.)

The real question is what kind of object is aimed at by the addict? In his paper ‘From saying to doing in the clinic of alcoholism and addiction’, Eric Laurent offers the answer that the object of addiction is not a substance but a semblance. Irrespective of the particular drug the addict depends on, the drug is not what the subject is really interested in when it comes to the ‘hit’. For Laurent, addiction is not about pleasure but the ‘verification of the colour of emptiness’.

“The first thing that drug addiction teaches psychoanalysis is that the object is a semblance, not a substance. It is precisely in drug addiction that we can find the most strongly sustained effort to incarnate the object of jouissance in an object of the world…. The true object of jouissance – if that word means anything – is death. The quest is not, as some say, for ‘some pleasure’; the quest is more precisely for the verification of the colour of emptiness [see E852, below] surrounding jouissance in the human being.” (Eric Laurent, ‘From saying to doing in the clinic of drug addiction and alcoholism’, in the Almanac of Psychoanalysis – Psychoanalytic stories after Freud and Lacan, p.138-139.)

Dealing with Jouissance

So what we can we learn from all of this about treating, managing, or otherwise dealing with jouissance? By way of summary we can highlight three points from Lacan’s work that can serve as a general guide:

1. Embrace castration by positivising a lack. The ethical dimension of this lesson is to not cede your desire; and to desire means to take lack as your object.

2. Mastering jouissance means loosening the bonds to the semblance, the unattainable object that is infinitely deferred. This means not becoming stuck in the paradoxical curvature of the space of jouissance that we sketched out above. This leads only to a kind of ‘negative infinity’.

3. Evacuate jouissance to the margins of your life in a fashion that would mimic the classical Freudian model of castration as the evacuation of jouissance to the margins of the body.

The philosophy behind these three lessons is encapsulated in one of the most beautiful lines from the Écrits, which ends ‘The Subversion of the Subject’ paper:

“Castration means that jouissance has to be refused in order to be attained on the inverse scale of the Law of desire.” (Écrits, 827).

By Owen Hewitson, LacanOnline.com

The article is taken from:

loading...

1 Comment

Transgression and Accelerationist Aestheticsby Steven Craig Hickman The deadlock of accelerationism as a political strategy has much to do with the aesthetic failure of transgression. They are really two sides of the same process. The acceleration of capitalism itself in the decades since 1980 has become a classic example of how we must be careful what we wish for— because we just might get it. As a result of the neoliberal “reforms” of the past thirty-five years or so, the full savagery of capitalism has been unleashed, no longer held back by the checks and balances of financial regulation and social welfare. At the same time, what Boltanski and Chiapello call the “new spirit of capitalism” successfully took up the subjective demands of the 1960s and 1970s and made them its own. Neoliberalism now offers us things like personal autonomy, sexual freedom, and individual “self-realization”; though of course, these often take on the sinister form of precarity, insecurity, and continual pressure to perform. Neoliberal capitalism today lures us with the prospect of living, in James’s words, “the most intense lives, lives of maximized (individual and social) investment and maximized return,” while at the same time it privatizes, expropriates, and extracts a surplus from everything in sight. In other words, the problem with accelerationism as a political strategy has to do with the fact that— like it or not— we are all accelerationists now. It has become increasingly clear that crises and contradictions do not lead to the demise of capitalism. Rather, they actually work to promote and advance capitalism, by providing it with its fuel. Crises do not endanger the capitalist order; rather, they are occasions for the dramas of “creative destruction” by means of which, phoenix-like, capitalism repeatedly renews itself. We are all caught within this loop. And accelerationism in philosophy or political economy offers us, at best, an exacerbated awareness of how we are trapped. Aesthetic accelerationism, unlike the politico-economic kind, does not claim any efficacy for its own operations. It revels in depicting situations where the worst depredations of capitalism have come to pass, and where people are not only unable to change things but are even unable to imagine trying to change things. This is capitalist realism in full effect. Aesthetic accelerationism does not even deny that its own intensities serve the aim of extracting surplus value and accumulating profit. The evident complicity and bad faith of these works, their reveling in the base passions that Nietzsche disdained, and their refusal to sustain outrage or claim the moral high ground: all these postures help to move us toward the disinterest and epiphenomenality of the aesthetic. So I don’t make any political claims for this sort of accelerationist art— indeed, I would undermine my whole argument were I to do so. But I do want to claim a certain aesthetic inefficacy for them— which is something that works of transgression and negativity cannot hope to attain today. —Steven Shaviro, No Speed Limit: Three Essays on Accelerationism The Article Is Taken From: by Guy Debord Our central purpose is the construction of situations, that is, the concrete construction of temporary settings of life and their transformation into a higher, passionate nature. We must develop an intervention directed by the complicated factors of two great components in perpetual interaction: the material setting of life and the behaviors that it incites and that overturn it. Our prospects for action on the environment lead, in their latest development, to the idea of a unitary urbanism. Unitary urbanism first becomes clear in the use of the whole of arts and techniques as means cooperating in an integral composition of the environment. This whole must be considered infinitely more extensive than the old influence of architecture on the traditional arts, or the current occasional application to anarchic urbanism of specialized techniques or of scientific investigations such as ecology. Unitary urbanism must control, for example, the acoustic environment as well as the distribution of different varieties of drink or food. It must take up the creation of new forms and the détournement of known forms of architecture and urbanism—as well as the détournement of the old poetry and cinema. Integral art, about which so much has been said, can only materialize at the level of urbanism. But it can no longer correspond with any traditional definitions of the aesthetic. In each of its experimental cities, unitary urbanism will work through a certain number of force fields, which we can temporarily designate by the standard expression district. Each district will be able to lead to a precise harmony, broken off from neighboring harmonies;or rather will be able to play on a maximum breaking up of internal harmony. Secondly, unitary urbanism is dynamic, i.e., in close touch with styles of behavior. The most reduced element of unitary urbanism is not the house but the architectural complex, which is the union of all the factors conditioning an environment, or a sequence of environments colliding at the scale of the constructed situation. Spatial development must take the affective realities that the experimental city will determine into account. One of our comrades has promoted a theory of states-of-mind districts, according to which each quarter of a city would tend to induce a single emotion, to which the subject will consciously expose herself or himself. It seems that such a project draws timely conclusions from an increasing depreciation of accidental primary emotions, and that its realization could contribute to accelerating this change. Comrades who call for a new architecture, a free architecture, must understand that this new architecture will not play at first on free, poetic lines and forms—in the sense that today’s “lyrical abstract” painting uses these words—but rather on the atmospheric effects of rooms, corridors, streets, atmospheres linked to the behaviors they contain. Architecture must advance by taking as its subject emotionally moving situations, more than emotionally moving forms, as the material it works with. And the experiments drawn from this subject will lead to unknown forms. Psychogeographical research, “study of the exact laws and precise effects of the geographical environment, consciously organized or not, acting directly on the affective deportment of individuals,” thus takes on its double meaning of active observation of today’s urban areas and the establishment of hypotheses on the structure of a situationist city. Psychogeography’s progress depends to a great extent on the statistical extension of its methods of observation, but principally on experimentation through concrete interventions in urbanism. Until this stage, the objective truth of even the first psychogeographical data cannot be ensured. But even if these data should turn out to be false, they would certainly be false solutions to a genuine problem. Our action on deportment, in connection with other desirable aspects of a revolution in customs, can be defined summarily as the invention of a new species of games. The most general aim must be to broaden the nonmediocre portion of life, to reduce its empty moments as much as possible. It may thus be spoken of as an enterprise of human life’s quantitative increase, more serious than the biological processes currently being studied. Even there, it implies a qualitative increase whose developments are unforeseeable. The situationist game stands out from the standard conception of the game by the radical negation of the ludic features of competition and of its separation from the stream of life. In contrast, the situationist game does not appear distinct from a moral choice, deciding what ensures the future reign of freedom and play. This is obviously linked to the certainty of the continual and rapid increase of leisure, at a level corresponding to that of our era’s productive forces. It is equally linked to the recognition of the fact that a battle over leisure is taking place before our eyes whose importance in the class struggle has not been sufficiently analyzed. To this day, the ruling class is succeeding in making use of the leisure that the revolutionary proletariat extracted from it by developing a vast industrial sector of leisure that is an unrivaled instrument for bestializing the proletariat through by-products of mystifying ideology and bourgeois tastes. One of the reasons for the American working class’s incapacity to become politicized should likely be sought amidst this abundance of televised baseness. By obtaining through collective pressure a slight rise in the price of its labor above the minimum necessary for the production of that labor, the proletariat not only enlarges its power of struggle but also widens the terrain of the struggle. New forms of this struggle then occur parallel with directly economic and political conflicts. Revolutionary propaganda can be said until now to have been constantly dominated in these forms of struggle in all countries where advanced industrial development has introduced them. That the necessary transformation of the base could be delayed by errors and weaknesses at the level of superstructures has unfortunately been proven by some of the twentieth century’s experiences. New forces must be hurled into the battle over leisure, and we will take up our position there. A first attempt at a new manner of deportment has already been achieved with what we have designated the dérive, which is the practice of a passionate uprooting through the hurried change of environments, as well as a means of studying psychogeography and situationist psychology. But the application of this will to ludic creation must be extended to all known forms of human relationships, and must, for example, influence the historical evolution of emotions like friendship and love. Everything leads to the belief that the main insight of our research lies in the hypothesis of constructions of situations. A man’s life is a sequence of chance situations, and if none of them is exactly similar to another, at the least these situations are, in their immense majority, so undifferentiated and so dull that they perfectly present the impression of similitude. The corollary of this state of affairs is that the singular, enchanting situations experienced in life strictly restrain and limit this life. We must try to construct situations, i.e., collective environments, ensembles of impressions determining the quality of a moment. If we take the simple example of a gathering of a group of individuals for a given time, and taking into account acquaintances and material means at our disposal, we must study which arrangement of the site, which selection of participants, and which incitement of events suit the desired environment. Surely the powers of a situation will broaden considerably in time and in space with the realizations of unitary urbanism or the education of a situationist generation. The construction of situations begins on the other side of the modern collapse of the idea of the theater. It is easy to see to what extent the very principle of the theater—nonintervention—is attached to the alienation of the old world. Inversely, we see how the most valid of revolutionary cultural explorations have sought to break the spectator’s psychological identification with the hero, so as to incite this spectator into activity by provoking his capacities to revolutionize his own life. The situation is thus made to be lived by its constructors. The role of the “public,” if not passive at least a walk-on, must ever diminish, while the share of those who cannot be called actors but, in a new meaning of the term, “livers,”1 will increase. Let us say that we have to multiply poetic objects and subjects (unfortunately so rare at present that the most trifling of them assumes an exaggerated emotional importance) and that we have to organize games of these poetic subjects among these poetic objects. There is our entire program, which is essentially ephemeral. Our situations will be without a future; they will be places where people are constantly coming and going. The unchanging nature of art, or of anything else, does not enter into our considerations, which are in earnest. The idea of eternity is the basest one a man could conceive of regarding his acts. Situationist techniques have yet to be invented, but we know that a task presents itself only where the material conditions necessary for its realization already exist, or are at least in the process of formation. We must begin with a small-scale, experimental phase. Undoubtedly we must draw up blueprints for situations, like scripts, despite their unavoidable inadequacy at the beginning. Therefore, we will have to introduce a system of notation whose accuracy will increase as experiments in construction teach us more. We will have to find or confirm laws, like those that make situationist emotion dependent upon an extreme concentration or an extreme dispersion of acts (classical tragedy providing an approximate image of the first case, and the dérive of the second). Besides the direct means that will be used toward precise ends, the construction of situations will require, in its affirmative phase, a new implementation of reproductive technologies. We could imagine, for example, live televisual projections of some aspects of one situation into another, bringing about modifications and interferences. But, more simply, cinematic “news”-reels might finally deserve their name if we establish a new documentary school dedicated to fixing the most meaningful moments of a situation for our archives, before the development of these elements has led to a different situation. The systematic construction of situations having to generate previously nonexistent feelings, the cinema will discover its greatest pedagogical role in the diffusion of these new passions. Situationist theory resolutely asserts a noncontinuous conception of life. The idea of consistency must be transferred from the perspective of the whole of a life—where it is a reactionary mystification founded on the belief in an immortal soul and, in the last analysis, on the division of labor—to the viewpoint of moments isolated from life, and of the construction of each moment by a unitary use of situationist means. In a classless society, it might be said, there will be no more painters, only situationists who, among other things, make paintings. Life’s chief emotional drama, after the never-ending conflict between desire and reality hostile to that desire, certainly appears to be the sensation of time’s passage. The situationist attitude consists in counting on time’s swift passing, unlike aesthetic processes which aim at the fixing of emotion. The situationist challenge to the passage of emotions and of time will be its wager on always gaining ground on change, on always going further in play and in the multiplication of moving periods. Obviously, it is not easy for us at this time to make such a wager; however, even were we to lose it a thousand times, there is no other progressive attitude to adopt. The situationist minority was first formed as a trend within the lettrist left wing, then within the Lettrist International, which it eventually controlled. The same objective impulse is leading several contemporary avant-garde groups to similar conclusions. Together we must discard all the relics of the recent past. We deem that today an agreement on a unified action among the revolutionary cultural avant-garde must implement such a program. We do not have formulas nor final results in mind. We are merely proposing an experimental research that will collectively lead in a few directions that we are in the process of defining, and in others that have yet to be defined. The very difficulty of arriving at the first situationist achievements is proof of the newness of the realm we are entering. What alters the way we see the streets is more important than what alters the way we see painting. Our working hypotheses will be reconsidered at each future upheaval, wherever it may come from. We will be told, chiefly by revolutionary intellectuals and artists who for reasons of taste put up with a certain powerlessness, that this “situationism” is quite disagreeable, that we have made nothing of beauty, that we would be better off speaking of Gide, and that no one sees any clear reason to be interested in us. People will shy away by reproaching us for repeating a number of viewpoints that have already caused too much scandal, and that express the simple desire to be noticed. They will become indignant about the conduct we have believed necessary to adopt on a few occasions in order to keep or to recover our distances. We reply:it is not a question of knowing whether this interests you, but rather of whether you yourself could become interesting under new conditions of cultural creation. Revolutionary artists and intellectuals, your role is not to shout that freedom is abused when we refuse to march with the enemies of freedom. You do not have to imitate bourgeois aesthetes who try to bring everything back to what has already been done, because the already-done does not make them uncomfortable. You know that creation is never pure. Your role is to search for what will give rise to the international avant-garde, to join in the constructive critique of its program, and to call for its support. excerpt from the book: Guy Debord and The Situationist Internationalist

An already old and corrupt nation, courageously shaking off the yoke of its monarchical government in order to adopt a republican one, can only maintain itself through many crimes; for it is already in crime, and if it wants to move from crime to virtue, in other words from a violent state to a peaceful one, it would fall into an inertia, of which its certain ruin would soon be the result.

Sade

What looks like politics, and imagines itself to be political, will one day unmask itself as a religious movement.

Kierkegaard

Today solitary, you who live apart, you one day will be a people. Those who have designated themselves will one day be a designated people, and from this people will be born the life that goes beyond man.

Nietzsche

loading...

It is necessary to produce and to eat: many things are necessary that are still nothing, and so it is with political agitation.

Who dreams, before having struggled to the end, of relinquishing his place to men it is impossible to look at without feeling the need to destroy? If nothing can be found beyond political activity, human avidity will meet nothing but a void.

WE ARE FEROCIOUSLY RELIGIOUS and, to the extent that our existence is the condemnation of everything that is recognized today, an inner exigency demands that we be equally imperious.

What we are starting is a war.

It is time to abandon the world of the civilized and its light. It is too late to be reasonable and educated-which has led to a life without appeal. Secretly or not, it is necessary to become completely different, or to cease being.

The world to which we have belonged offers nothing to love outside of each individual insufficiency: its existence is limited to utility. A world that cannot be loved to the point of death-in the same way that a man loves a woman represents only self-interest and the obligation to work. If it is compared to worlds gone by, it is hideous, and appears as the most failed of all. In past worlds, it was possible to lose oneself in ecstasy, which is impossible in our world of educated vulgarity. The advantages of civilization are offset by the way men profit from them: men today profit in order to become the most degraded beings that have ever existed. Life has always taken place in a tumult without apparent cohesion, but it only finds its grandeur and its reality in ecstasy and in ecstatic love. He who tries to ignore or misunderstand ecstasy is an incomplete being whose thought is reduced to analysis. Existence is not only an agitated void, it is a dance that forces one to dance with fanaticism. Thought that does not have a dead fragment as its object has the inner existence of flames. It is necessary to become sufficiently firm and unshaken so that the existence of the world of civilization finally appears uncertain. It is useless to respond to those who are able to believe in the existence of this world and who take their authority from it; if they speak, it is possible to look at them without hearing them and, even when one looks at them, to "see" only what exists far behind them. It is necessary to refuse boredom and live only for fascination. On this path, it is vain to become restless and seek to attract those who have idle whims, such as passing the time, laughing, or becoming individually bizarre. It is necessary to go forward without looking back and without taking into account those who do not have the strength to forget immediate reality.

Human life is exhausted from serving as the head of, or the reason for, the universe. To the extent that it becomes this head and this reason, to the extent that it becomes necessary to the universe, it accepts servitude. If it is not free, existence becomes empty or neutral and, if it is free, it is in play. The Earth, as long as it only gave rise to cataclysms, trees, and birds, was a free universe; the fascination of freedom was tarnished when the Earth produced a being who demanded necessity as a law above the universe. Man however has remained free not to respond to any necessity; he is free to resemble everything that is not himself in the universe. He can set aside the thought that it is he or God who keeps the rest of things from being absurd.

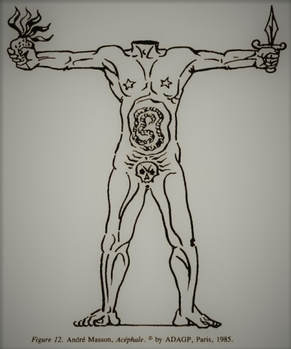

Man has escaped from his head just as the condemned man has escaped from his prison. He has found beyond himself not God, who is the prohibition against crime, but a being who is unaware of prohibition. Beyond what I am, I meet a being who makes me laugh because he is headless; this fills me with dread because he is made of innocence and crime; he holds a steel weapon in his left hand, flames like those of a Sacred Heart in his right. He reunites in the same eruption Birth and Death. He is not a man. He is not a god either. He is not me but he is more than me: his stomach is the labyrinth in which he has lost himself, loses me with him, and in which I discover myself as him, in other words as a monster.

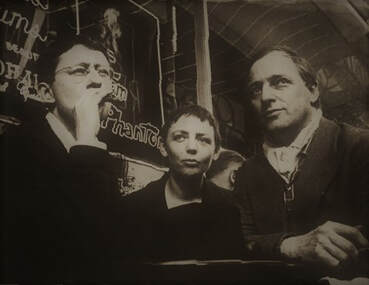

What I have thought or represented, I have not thought or represented alone. I am writing in a little cold house in a village of fishermen; a dog has just barked in the night. My room is next to the kitchen where Andre Masson is happily moving around and singing; at this very moment, as I write, he has just put on the phonograph a recording ofthe overture to Don Giovanni; more than anything else, the overture to Don Giovanni ties my lot in life to a challenge that opens me to a rapturous escape from the self. At this very moment, I am watching this acephalic being, this intruder composed of two equally excited obsessions, become the "Tomb of Don Giovanni." When, a few days ago, I was with Andre Masson in this kitchen, seated, a glass of wine in my hand, he suddenly talked of his own death and the death of his family, his eyes fixed, suffering, almost screaming that it was necessary for it to become a tender and passionate death, screaming his hatred for a world that weighs down even on death with its employee's paw-and I was no longer able to doubt that the lot and the infinite tumult of human life were open to those who could no longer exist as empty eye sockets, but as seers swept away by an overwhelming dream they could not own.

Tossa, April 29, 1936

excerpt from the book: Visions of Excess (Selected Writings, 1927-1939) by Georges Bataille

loading...

WERE there any limits to Vaughan's irony? When I returned from the bar he was leaning against the windowsill of the Lincoln, rolling the last of four cigarettes with the hash kit kept in a tobacco bag in the dashboard locker. Two sharp-faced airport whores, barely older than schoolchildren, were arguing with him through the window. 'Where the hell do you think you were going?' Vaughan took from me the two wine bottles I had bought. He rolled the cigarettes on to the instrument binnacle, then resumed his discussion with the young women. They were arguing in an abstract way about time and price. Trying to ignore their voices, and the massed traffic moving below the supermarket, I watched the aircraft taking off from London Airport across the western perimeter fence, constellations of green and red lights that seemed to be shifting about large pieces of the sky. The two women peered into the car, sizing me up in a one-second glance. The taller of the two, whom Vaughan had already assigned to me, was a passive blonde with unintelligent eyes focused three inches above my head. She pointed to me with her plastic handbag. 'Can he drive?' 'Of course - a few drinks always make a car go better.' Vaughan twirled the wine bottles like dumb-bells, herding the women into the car. As the second girl, with short black hair and a boy's narrow-hipped body, opened the passenger door, Vaughan handed a bottle to her. Lifting her chin, he put his fingers in her mouth. He plucked out the knot of gum and flicked it away into the darkness. 'Let's get rid of that - I don't want you blowing it up my urethra. Adjusting myself to the unfamiliar controls, I started the engine and crossed the forecourt to the slip road. Above us, along Western Avenue, the traffic stream edged its way towards London Airport. Vaughan opened a wine bottle and passed it to the blonde sitting beside me in the front seat. He lit the first of the four cigarettes he had rolled. Already one elbow was between the dark-haired girl's thighs, raising her skirt to reveal her black crotch. He drew the cork from the second bottle and pressed the wet end against her white teeth. In the rearview mirror I could see her avoiding Vaughan's mouth. She inhaled the cigarette smoke, her hand resting on Vaughan's groin. Vaughan lay back, inspecting her small features with a detached gaze, looking her body up and down like an acrobat calculating the traverses and impacts of a gymnastic feat involving a large amount of complex equipment. With his right hand he opened the zip of his trousers, then arched his hips forward to free his penis. The girl held it in one hand, the other steadying the wine bottle as I let the car surge away from the traffic lights. Vaughan unbuttoned her shirt with his scarred fingers and brought out her small breast. Examining the breast, Vaughan gripped the nipple between thumb and forefinger, extruding it forward in a peculiar manual hold, as if fitting together a piece of unusual laboratory equipment. Brake-lights flared twenty yards ahead of me. Horns sounded from the line of cars in the rear. As their headlamps pulsed I moved the shift lever into drive and pressed the accelerator, jerking the car forward. Vaughan and the girl rolled back against the rear seat. The cabin was lit only by the instrument dials, and by the headlamps and tail-lights in the crowded traffic lanes around us. Vaughan had freed both the girl's breasts, nursing them with his palm. His scarred lips sucked at the thick smoke from the crumbling butt of the cigarette. He took the wine bottle and raised it to her mouth. As she drank he lifted her legs so that her heels rested on the seat, and began to move his penis against the skin of her thighs, drawing it first across the black vinyl and then pressing the glans against her heel and ankle bone, as if testing the possible continuity of these two materials before taking part in a sexual act involving both the car and this young woman. He lay against the rear seat, left arm stretched above the girl's head, embracing this slab of over-sprung black vinyl. His hand was raised at right-angles to his forearm, measuring out the geometry of the chromium roof sill, while his right hand moved down the girl's thighs and cupped her buttocks. Squatting there with her heels under her buttocks, the girl opened her thighs to expose her small pubic triangle, the labia open and protruded. Through the smoke lifting from the ashtray Vaughan studied the girl's body in a good-humoured way. Beside him, the girl's small, serious face was lit by the headlamps of the cars creeping forwards in the traffic files. The damp, inhaled smoke of burnt resin filled the interior of the car. My head seemed to float on these fumes. Somewhere ahead, beyond these immense lines of nearly stationary vehicles, was the illuminated plateau of the airport, but I felt barely able to do more than point the large car along the centre lane. The blonde woman in the front seat offered me a drink from the wine bottle. When I declined she leaned her head against my shoulder, giving a playful touch to the steering wheel. I put my arm around her shoulder, aware of her hand on my thigh. I waited until we stopped again, and adjusted the driving mirror so that I could see into the rear seat. Vaughan had moved his thumb into the girl's vagina, forefinger into her rectum, as she sat back with her knees against her shoulders, drawing mechanically at the second of the cigarettes. His left hand took the girl's breast, his ring- and forefingers propping up the nipple like a miniature crutch. Holding these elements of the girl's body in his formalized pose, he began to rock his hips back and forth, driving his penis into the girl's hand. When she tried to move his fingers from her vulva Vaughan knocked her hand away with his elbow, holding the fingers securely in her body. He straightened his legs, rotating himself around the passenger compartment so that his hips rested on the edge of the seat. Braced on his left elbow, he continued to work himself against the girl's hand, as if taking part in a dance of severely stylized postures that celebrated the design and electronics, speed and direction of an advanced kind of automobile. This marriage of sex and technology reached its climax as the traffic divided at the airport overpass and we began to move forwards in the northbound lane. As the car travelled for the first time at twenty miles an hour Vaughan drew his fingers from the girl's vulva and anus, rotated his hips and inserted his penis in her vagina. Headlamps flared above us as the stream of cars moved up the slope of the overpass. In the rear-view mirror I could still see Vaughan and the girl, their bodies lit by the car behind, reflected in the black trunk of the Lincoln and a hundred points of the interior trim. In the chromium ashtray I saw the girl's left breast and erect nipple. In the vinyl window gutter I saw deformed sections of Vaughan's thighs and her abdomen forming a bizarre anatomical junction. Vaughan lifted the young woman astride him, his penis entering her vagina again. In a triptych of images reflected in the speedometer, the clock and revolution counter, the sexual act between Vaughan and this young woman took place in the hooded grottoes of these luminescent dials, moderated by the surging needle of the speedometer. The jutting carapace of the instrument panel and the stylized sculpture of the steering column shroud reflected a dozen images of her rising and falling buttocks. As I propelled the car at fifty miles an hour along the open deck of the overpass Vaughan arched his back and lifted the young woman into the full glare of the headlamps behind us. Her sharp breasts flashed within the chromium and glass cage of the speeding car. Vaughan's strong pelvic spasms coincided with the thudding passage of the lamp standards anchored in the overpass at hundred-yard intervals. As each one approached his hips kicked into the girl, driving his penis into her vagina, his hands splaying her buttocks to reveal her anus as the yellow light filled the car. We reached the end of the overpass. The red glow of brakelights burned the night air, touching the images of Vaughan and the young woman with a roseate light. Controlling the car, I drove down the ramp towards the traffic junction. Vaughan changed the tempo of his pelvic motion, drawing the young woman on top of himself and extending her legs along his own. They lay diagonally across the rear seat, Vaughan taking first her left nipple in his mouth, then the right, his finger in her anus, stroking her rectum to the rhythm of the passing cars, matching his own movements to the play of light sweeping transversely across the roof of the car. I pushed away the blonde girl lying against my shoulder. I realized that I could almost control the sexual act behind me by the way in which I drove the car. Playfully, Vaughan responded to different types of street furniture and roadside trim. As we left London Airport, heading inwards towards the city on the fast access roads, his rhythm became faster, his hands under the girl's buttocks forcing her up and down as if some scanning device in his brain was increasingly agitated by the high office blocks. At the end of the orgasm he was almost standing behind me in the car, legs outstretched, head against the rear seat, hands propping up his own buttocks as he carried the girl on his hips. Half an hour later I had turned back to the airport and stopped the car in the shadows of the multi-storey carpark facing the Oceanic Terminal. The girl at last managed to pull herself from Vaughan, who lay exhausted against the rear seat. Clumsily, she reassembled herself, remonstrating with Vaughan and the drowsy blonde in the front seat. Vaughan's semen ran down her left thigh on to the black vinyl of the seat. The ivory globes searched for the steepest gradient to the central sulcus of the seat. I stepped from the car and paid the two women. When they had gone, carrying their hard loins back to the neon-lit concourses, I waited beside the car. Vaughan was staring at the terraced cliff of the car-park, his eyes following the canted floors, as if trying to recognize everything that had passed between himself and the dark-haired girl. excerpt from the book: Crash by J.G.Ballard

by J.G. Ballard

The evening deepened, and the apartment building withdrew into the darkness. As usual at this hour, the high-rise was silent, as if everyone in the huge building was passing through a border zone. On the roof the dogs whimpered to themselves. Royal blew out the candles in the dining-room and made his way up the steps to the penthouse. Reflecting the distant lights of the neighbouring high-rises, the chromium shafts of the callisthenics machine seemed to move up and down like columns of mercury, a complex device recording the shifting psychological levels of the residents below. As Royal stepped on to the roof the darkness was lit by the white forms of hundreds of birds. Their wings flared in the dark air as they struggled to find a perch on the crowded elevator heads and balustrades.

Royal waited until they surrounded him, steering their beaks away from his legs with his stick. He felt himself becoming calm again. If the women and the other members of his dwindling entourage had decided to leave him, so much the better. Here in the darkness among the birds, listening to them swoop and cry, the dogs whimpering in the children's sculpture-garden, he felt most at home. He was convinced more than ever that the birds were attracted here by his own presence.

loading...

Royal scattered the birds out of his way and pushed back the gates of the sculpture-garden. As they recognized him, the dogs began to whine and strain, pulling against their leads. These retrievers, poodles and dachshunds were all that remained of the hundred or so animals who had once lived in the upper floors of the high-rise. They were kept here as a strategic food reserve, but Royal had seen to it that few of them had been eaten. The dogs formed his personal hunting pack, to be kept until the final confrontation when he would lead them down into the building, and throw open the windows of the barricaded apartments to admit the birds.

The dogs pulled at his legs, their leads entangled around the play-sculptures. Even Royal's favourite, the white alsatian, was restless and on edge. Royal tried to settle it, running his hands over the luminous but still bloodstained coat. The dog butted him nervously, knocking him back across the empty food-pails.