|

Historical riots represent a challenge for the state because, in demanding the departure of those who rule it, they invariably expose it to a brutal, unprepared change, even to the possibility of its complete collapse (that is precisely what happened in Iran, thirty years ago, to the Shah's monarchical regime). At the same time, riots do not possess all the keys - far from it to the nature and extent of the change to which they expose the state. What is going to happen in the state is in no wise prefigured by a riot.

Admittedly, in mass movements with a historical dimension there are always people who sincerely believe the opposite. They think that the popular democratic practices of the movement (of any historical riot, no matter when and where it occurs) form a kind of paradigm for the state to come. Egalitarian assemblies are held; everyone has the right to speak; social, religious, racial, national, sexual and intellectual differences are no longer of any significance. Decisions are always collective. In appearance at least: seasoned militants know how to prepare for an assembly by a prior, closed meeting that will in fact remain secret. But no matter, it is indeed true that decisions will invariably be unanimous, because the strongest, most appropriate proposal emerges from the discussion. And it can then be said that 'legislative' power, which formulates the new directive, not only coincides with 'executive power', which organizes its practical consequences, but also with the whole active people symbolized by the assembly.

Why not extend these features of mass democracy, which are so powerful and inspiring, to the state in its entirety? Quite simply because between the democracy of the riot and the routine, repressive, blind system of state decisions - even, and especially, when they claim to be 'democratic' - there is such a wide gulf that Marx could only imagine overcoming it at the end of a process of the state's withering away. And, to be brought to a successful conclusion, that process required not mass democracy everywhere, but its dialectical opposite: a transitional dictatorship which was compacted and implacable.

loading...

Marx was unquestionably right, and I shall return to the rational paradox of an inevitable continuity between the egalitarian democracy established within itself by an historical riot and the popular dictatorship exercised without, in the direction of enemies and suspects, whereby an attempt is made to achieve political fidelity to the riot.

For now it suffices for us to note that a historical riot does not by itself offer any alternative to the power it intends to overthrow. There is a very important difference between 'historical riot' and 'revolution': the second, at least since Lenin, has been regarded as possessing within itself the resources required for an immediate seizure of power.

That is why rioters have always complained about the fact that the new regime, following the riotous overthrow of the previous one, is in the main identical to it. The prototype of such similarity is the construction of a regime dominated by political personnel from the putative 'opposition' to the Empire after the fall of Napoleon III, the lost war and the riots of 4 September 1870. To make it perfectly clear whose side it was on, this 'new' government was to display an especial antipopular ferocity a few months later, by remorselessly massacring thousands of communard workers.

The communist party, such as it was conceived by the Russian Social Democratic Workers' Party and then the Bolsheviks, is a structure which, derived from a rigorous analysis of the Paris Commune by Lenin, declared itself capable of incorporating an alternative to the existing government and founding a new state after the complete destruction of the old Tsarist apparatus.

When the figure of riot becomes a political figure - in other words, when it possesses within itself the political personnel it requires and resort to the state's professional nags becomes unnecessary - we can say that what has arrived is the end if the intervallic period, because a new politics has been able to seize on the rebirth of History symbolized by a historical riot.

To return to the historical riots in the Arab world, especially Egypt and Tunisia, we already know that they are going to continue while becoming divided. Some of the rioters - the youngest, the most determined or the best organized - are going to declare that the transitional governments which have been established with difficulty, and which often conceal the persistence of the most important institutions of the old regime (for example, the army in Egypt), are so remote from the popular movement that they do not want them any more than they did Ben Ali or Mubarak. But for the moment these protests are not generating the idea on whose basis fidelity to the riot can be organized. Hence a vibrant indecision which, from a purely formal standpoint, closely equates the situation in the Arab world with situations already witnessed in the nineteenth century.

Ultimately, we cannot avoid the question: what criteria make it possible to evaluate a riot, to assess the scope of the historical reawakening it incorporates?

From the outset, the Western powers, and the media dependent on them, have had a ready-made answer. According to them, the desire inspiring the riots in the Arab countries is 'freedom' in the sense given this term by Westerners - namely, 'freedom of opinion' in the fixed framework of unbridled capitalism ('free enterprise') and a state based on parliamentary representation ('free elections', which select between various practically indistinguishable managers of the established system).

Basically, our rulers and our dominant media have suggested a simple interpretation of the riots in the Arab world: what is expressed in them is what might be called a desire for the West. A desire to 'enjoy' everything that we, the drowsy, satiated inhabitants of the affluent countries, already 'enjoy' . A desire finally to be included in the 'civilized world' which Westerners, incorrigible descendants of racist colonists, are so certain of representing that they set up international 'courts' to judge anyone who asserts different values (which are indeed sometimes disreputable), or so much as affects to shake off the oppressive tutelage of the 'international community' (admittedly sometimes in purely self-interested fashion). In so doing, Westerners wrapped in the flag of Right forget that their alleged power to state the Good is nothing but the modernized name for imperial interventionism.

Any mass movement is obviously an urgent demand for liberation. With respect to regimes as despotic, corrupt and in thrall to imperial beck and call as those of Ben Ali and Mubarak, such a demand is wholly legitimate. That this desire as such is a desire for the West is infinitely more debatable.

It must be remembered that the West as a power has not hitherto shown any evidence that it was in the least concerned with organizing freedom in the places it intervenes in, often with arms. What counts for our 'civilized' men is: 'Are you with us or against us?' This gives the phrase 'with us' the meaning of a slavish inclusion in the planetary market economy, organized in the relevant countries by corrupt personnel, in close collaboration with a counterrevolutionary police force and army, trained, equipped and commanded by officers, secret agents and racketeers who are just like back home. 'Friendly countries' such as Saudi Arabia, Pakistan, Nigeria, Mexico and many others are just as despotic and corrupt as Ben Ali's Tunisia or Mubarak's Egypt, if not much more so. But we scarcely hear those who emerged on the occasion of the events in Tunisia or Egypt as ardent defenders of all riots in favour of freedom pronouncing on that subject. One senses that our states prefer the firm calm ensured by friendly despots to the uncertainty of riots. But once a riot is open to being interpreted as a desire for the West, and even better ends up being such, our politicians and media will accord it a warm reception.

However, such an outcome is not guaranteed. The very fact that, via the handy megaphone of BernardHenri Levy, the French and British have ended up purely and simply inventing rag-tag and bob tail 'rebels' in Libya -of whom the only real effective ones have declared themselves to be ex-al-Qaeda (what a paradox!), but all of whom for the moment are under their heel (Libya is the only place in the world where people have the absurd idea of shouting 'Long live Sarkozy!') - arming them, leading them and guaranteeing them the supporting fire of their air forces, demonstrates the extent to which our governments ultimately fear the expression in genuine rebellions of anything other than an inordinate love of imperial civilizations. That people should be referring, after five months of action by French and British planes with American logistical support, their attack helicopters, and their officers and agents on the ground, to a moving 'rebel victory' is frankly ridiculous.

But this is the kind of victory (Alain Juppe stating, in a telling admission, 'We did the job') that Westerners adore. For when genuine popular rebellions are involved, they cannot help thinking that perhaps, after all, they are dealing with people who do not wish to shout themselves hoarse in support of Cameron, Sarkozy or Obama. Maybe - as their anxiety mounts all these episodes contain an Idea, as yet unformulated, which is highly displeasing to them. A conception of democracy completely opposed to their own, perhaps. In this state of uncertainty, they conclude, let us get our machine guns ready and confirm that they are in working order.

In these conditions we must attempt to define more precisely what a popular movement reducible to a 'desire for the West' is or might be; and what the current riots, should they rise above this lethal temptation, could be.

Let us try, then. A riot subject to a desire for the West takes the immediate form of an anti -despotic riot, whose negative, popular power is indeed that of the crowd, but whose affirmative power has no other norm than those vaunted by the West. A popular movement corresponding to this definition has every chance of ending in very modest constitutional reforms and elections firmly controlled by the 'international community'. From these, to the general surprise of supporters of the riot, there will emerge victorious either some well-known hired guns of Western interests, or a version of those 'moderate Islamists' from whom our rulers are gradually learning that there is nothing to fear. I propose to say that at the end of such a process we will have witnessed a phenomenon of Western inclusion.

Among us the dominant interpretation of what is happening is that this phenomenon is the natural, legitimate outcome of the riots in the Arab world under the rubric of 'victory of democracy' .

Moreover, this explains why, by contrast, riots are brutally repressed and execrated when they occur at home. If a 'good riot' demands inclusion in the West, why on earth rise up where this inclusion is well established, in our robust civilized democracy? From time to time the flea-ridden, the Arabs, the blacks, the Orientals and other workers from hell may, without exaggeration, demand to be 'like us' - all the more so because it will not happen tomorrow, and in the meantime the good old colonial plunder that fuels our serenity will continue in various forms. At home, on the other hand, they only have the right to work and vote in silence. If not, look out! Cameron and his little London gulag for inner-city youth, Sarkozy and his anti-rabble Karchers, are guarding the walls of civilization.

If it is true, as Marx foresaw, that the space of realization of emancipatory ideas is global (something, incidentally, that was not really true of twentieth century revolutions), then a phenomenon of Western inclusion cannot be regarded as genuine change. What would be a genuine change would be an exit from the West, a 'de-Westernization', and it would take the form of an exclusion. A daydream, you will say. But it could be that it is right there, in front of our eyes. And in any event this is what we must dream, because this dream makes it possible, without reneging on everything we have stood for or sinking into the 'no future' of nihilism, to go through the painful years of an intervallic period.

ALAIN BADIOU/THE REBIRTH OF HISTORY/ Times Of Riots and Uprisings

loading...

0 Comments

It is this fundamental turnaround that the new reversal of the definition of man records: man is a will served by an intelligence. Will is the rational power that must be delivered from the quarrels between the idea-ists and the thing-ists. It is also in this sense that the Cartesian equality of the cogito must be specified. In place of the thinking subject who only knows himself by withdrawing from all the senses and from all bodies, we have a new thinking subject who is aware of himself through the action he exerts on himself as on other bodies. Here is how Jacotot, according to the principles of universal teaching, made his own translation of Descartes’s famous analysis of the piece of wax: I want to look and I see. I want to listen and I hear. I want to touch and my arm reaches out, wanders along the surfaces of objects or penetrates into their interior; my hand opens, develops, extends, closes up; my fingers spread out or move together by obeying my will. In that act of touching, I know only my will to touch. That will is neither my hand, nor my brain, nor my touching. That will is me, my soul, it is my power, it is my faculty. I feel that will, it is present in me, it is myself; as for the manner in which I am obeyed, that I don’t feel, that I only know by its acts. . . . I consider ideation like touching. I have sensations when I like; I order my senses to bring them to me. I have ideas when I like; I order my intelligence to look for them, to feel. The hand and the intelligence are slaves, each with its own attributes. Man is a will served by an intelligence. I have ideas when I like. Descartes knew well the power of will over understanding. But he knew it precisely as the power of the false, as the cause of error: the haste to affirm when the idea isn’t clear and distinct. The opposite must be said: it is the lack of will that causes intelligence to make mistakes. The mind’s original sin is not haste, but distraction, absence. “To act without will or reflection does not produce an intellectual act. The effect that results from this cannot be classed among the products of intelligence, nor can it be compared to them. One can see neither more nor less action in inactivity; there is nothing. Idiocy is not a faculty; it is the absence or the slumber or the relaxation of [intelligence].” Intelligence’s act is to see and to compare what has been seen. It sees at first by chance. It must seek to repeat, to create the conditions to re-see what it has seen, in order to see similar facts, in order to see facts that could be the cause of what it has seen. It must also form words, sentences, and figures, in order to tell others what it has seen. In short, the most frequent mode of exercising intelligence, much to the dissatisfaction of geniuses, is repetition. And repetition is boring. The first vice is laziness. It is easier to absent oneself, to half-see, to say what one hasn’t seen, to say what one believes one sees. “Absent” sentences are formed in this way, the “therefores” that translate no mental adventure. “I can’t” is one of these absent sentences. “I can’t” is not the name of any fact. Nothing happens in the mind that corresponds to that assertion. Properly speaking, it doesn’t want to say anything. Speech is thus filled or emptied of meaning depending on whether the will compels or relaxes the workings of the intelligence. Meaning is the work of the will. This is the secret of universal teaching. It is also the secret of those we call geniuses: the relentless work to bend the body to necessary habits, to compel the intelligence to new ideas, to new ways of expressing them; to redo on purpose what chance once produced, and to reverse unhappy circumstances into occasions for success: This is true for orators as for children. The former are formed in assemblies as we are formed in life. . . . He who, by chance, made people laugh at his expense at the last session could learn to get a laugh whenever he wants to were he to study all the relations that led to the guffaws that so disconcerted him and made him close his mouth forever. Such was Demosthenes’ debut. By making people laugh without meaning to, he learned how he could excite peals of laughter against Aeschines. But Demosthenes wasn’t lazy. He couldn’t be. Once more universal teaching proclaims: an individual can do anything he wants. But we must not mistake what wanting means. Universal teaching is not the key to success granted to the enterprising who explore the prodigious powers of the will. Nothing could be more opposed to the thought of emancipation than that advertising slogan. And the Founder became irritated when disciples opened their school under the slogan, “Whoever wants to is able to.” The only slogan that had value was “The equality of intelligence.” Universal teaching is not an expedient method. It is undoubtedly true that the ambitious and the conquerors gave ruthless illustration of it. Their passion was an inexhaustible source of ideas, and they quickly understood how to direct generals, scholars, or financiers faultlessly in sciences they themselves did not know. But what interests us is not this theatrical effect. What the ambitious gain in the way of intellectual power by not judging themselves inferior to anyone, they lose by judging themselves superior to everyone else. What interests us is the exploration of the powers of any man when he judges himself equal to everyone else and judges everyone else equal to him. By the will we mean that self-reflection by the reasonable being who knows himself in the act. It is this threshold of rationality, this consciousness of and esteem for the self as a reasonable being acting, that nourishes the movement of the intelligence. The reasonable being is first of all a being who knows his power, who doesn’t lie to himself about it. Jacques Rancière/The Ignorant Schoolmaster (Five Lessons in Intellectual Emancipation) Precisely, say the superior minds. The opposite fact is obvious. That intelligence is unequal is evident to everyone. First of all, in nature, no two beings are identical. Look at the leaves falling from the tree. They seem exactly the same to you. Look more closely and disabuse yourself. Among the thousands of leaves, there are no two alike. Individuality is the law of the world. And how could this law that applies to vegetation not apply a fortiori to this being so infinitely more elevated in the vital hierarchy that is human intelligence? Therefore, each intelligence is different. Second, there have always been, there always will be, there are everywhere, beings unequally gifted for intellectual things: scholars and ignorant ones, intelligent people and fools, open minds and closed minds. We know what is said on the subject: the difference in circumstances, social milieu, education . . . Well, let’s do an experiment: let’s take two children who come from the same milieu, raised in the same way. Let’s take two brothers, put them in the same school, make them do the same exercises. And what will we see? One will do better than the other. There is therefore an intrinsic difference. And the difference results from this: one of the two is more intelligent, more gifted; he has more resources than the other. Therefore, you can clearly see that intelligence is unequal. How to respond to this evidence? Let’s begin at the beginning: with the leaves that superior minds are so fond of. We fully recognize that they are as different as people so minded could desire. We only ask: how does one move from the difference between leaves to the inequality of intelligence? Inequality is only a kind of difference, and it is not the one spoken about in the case of leaves. A leaf is a material thing while a mind is immaterial. How can one infer, without paralogism, the properties of the mind from the properties of matter? It is true that this terrain is now occupied by some fierce adversaries: physiologists. The properties of the mind, according to the most radical of them, are in fact the properties of the human brain. Difference and inequality hold sway there just as in the configuration and functioning of all the other organs in the human body. The brain weighs this much, so intelligence is worth that much. Phrenologists and cranioscopists are busy with all this: this man, they tell us, has the skull of a genius; this other doesn’t have a head for mathematics. Let’s leave these protubérants to the examination of their protuberances and get down to the serious business. One can imagine a consequent materialism that would be concerned only with brains, and that could apply to them everything that is applied to material beings. And so, effectively, the propositions of intellectual emancipation would be nothing but the dreams of bizarre brains, stricken with a particular form of that old mental malady called melancholia. In this case, superior minds— that is to say, superior brains— would in fact have authority over inferior minds in the same way man has authority over animals. If this were simply the case, nobody would discuss the inequality of intelligence. Superior brains would not go to the unnecessary trouble of proving their superiority over inferior minds— in capable, by definition, of understanding them. They would be content to dominate them. And they wouldn’t run into any obstacles: their intellectual superiority would be demonstrated by the fact of that domination, just like physical superiority. There would be no more need for laws, assemblies, and governments in the political order than there would be for teaching, explications, and academies in the intellectual order. Such is not the case. We have governments and laws. We have superior minds that try to teach and convince inferior minds. What is even stranger, the apostles of the inequality of intelligence, in their immense majority, don’t believe the physiologists and make fun of the phrenologists. The superiority they boast of can’t be measured, they believe, by instruments. Materialism would be an easy explanation for their superiority, but they make a different case. Their superiority is spiritual. They are spiritualists, above all, because of their own good opinion of themselves. They believe in the immaterial and immortal soul. But how can something immaterial be susceptible to more or less? This is the superior minds’ contradiction. They want an immortal soul, a mind distinct from matter, and they want different degrees of intelligence. But it’s matter that makes differences. If one insists on inequality, one must accept the theory of cerebral loci; if one insists on the spiritual principle, one must say that it is the same intelligence that applies, in different circumstances, to different material objects. But the superior minds want neither a superiority that would be only material nor a spirituality that would make them the equals of their inferiors. They lay claim to the differences of materialists in the midst of the elevation that belongs to immateriality. They paint the cranioscopist’s skulls with the innate gifts of intelligence. And yet they know very well that the shoe pinches, and they also know they have to concede something to the inferiors, even if only provisionally. Here, then, is how they arrange things: there is in every man, they say, an immaterial soul. This soul permits even the most humble to know the great truths of good and evil, of conscience and duty, of God and judgment. In this we are all equal, and we will even concede that the humble often teach us in these matters. Let them be satisfied with this and not pretend to intellectual capacities that are the privilege— often dearly paid for— of those whose task is to watch over the general interests of society. And don’t come back and tell us that these differences are purely social. Look instead at these two children, who come from the same milieu, taught by the same masters. One succeeds, the other doesn’t. Therefore ... So be it! Let’s look then at your children and your therefore. One succeeds better than the other, this is a fact. If he succeeds better, you say, this is because he is more intelligent. Here the explanation becomes obscure. Have you shown another fact that would be the cause of the first? If a physiologist found one of the brains to be narrower or lighter than the other, this would be a fact. He could therefore-ize deservedly. But you haven’t shown us another fact. By saying “ He is more intelligent,” you have simply summed up the ideas that tell the story of the fact. You have given it a name. But the name of a fact is not its cause, only, at best, its metaphor. The first time you told the story of the fact by saying, “He succeeds better.” In your retelling of it you used another name: “He is more intelligent.” But there is no more in the second statement than in the first. “This man does better than the other because he is smarter. That means precisely: he does better because he does better. . . . This young man has more resources, they say. ‘What is more resources?’ I ask, and they start to tell me the story of the two children again; so more resources, I say to myself, means in French the set of facts I just heard; but that expression doesn’t explain them at all.” It’s impossible, therefore, to break out of the circle. One must show the cause of the inequality, at the risk of borrowing it from the protubérants, or be reduced to merely stating a tautology. The inequality of intelligence explains the inequality of intellectual manifestations in the way the virtus dormitiva explains the effects of opium. Jacques Rancière -The Ignorant Schoolmaster (Five Lessons in Intellectual Emancipation) by Jacques Ranciere To recapitulate: politics exists wherever the count of parts and parties of society is disturbed by the inscription of a part of those who have no part. It begins when the equality of anyone and everyone is inscribed in the liberty of the people. This liberty of the people is an empty property, an improper property through which those who are nothing purport that their group is identical to the whole of the community. Politics exists as long as singular forms of subjectification repeat the forms of the original inscription of the identity between the whole of the community and the nothing that separates it from itself-in other words, the sole count of its parts. Politics ceases wherever this gap no longer has any place, wherever the whole of the community is reduced to the sum of its parts with nothing left over. There are several ways of thinking of the whole as the sole sum of its parts. The sum may be made up of individuals, small machines intensely exploiting their own freedom to desire, to undertake, and to enjoy. It may be made up of social groups building their interests as responsible partners. It may be made up of communities, each endowed with recognition of its identity and its culture. In this regard, the consensual state is tolerant. But what it no longer tolerates is the supernumerary party, the one that throws out the count of the community. What it needs is real parties, having both their own properties and the common property of the whole. What it cannot tolerate is a nothing that is all. The consensus system rests on these solid axioms: the whole is all, nothing is nothing. By eliminating the parasitical entities of political subjectification, little by little the identity of the whole with the all is obtained, which is the identity of the principle of the whole with that of each of its parts, beneficiaries of the whole. This identity is called humanity. And this is where the trouble starts. The consensus system celebrated its victory over totalitarianism as the final victory of law over nonlaw and of realism over utopias. It was gearing up to welcome into its space-freed from politics and called Europe-the democracies born of the destruction of the totalitarian states. But just about everywhere .it looks it sees the landscape of humanity, freed from totalitarianism and the utopias, as a landscape of fundamentalisms of identity. On the ruins of the totalitarian states, ethnicism and ethnic wars break out. Religion and religious states once consecrated as a natural barrier to Soviet expansion take on the figure of the fundamentalist threat. This threat even springs up in the heart of consensus states, wherever those workers who are no longer anything more than immigrants live, wherever individuals turn out to be incapable of meeting the requirement that they militate for their own integrity. In the face of this threat, consensus communities witness the rebirth of sheer rejection of those whose ethnicity or religion cannot be borne. The consensus system represents itself to itself as the world of law as opposed to the world of nonlawthe world of barbaric identity, religion, or ethnicity. But in that world of subjects strictly identified with their ethnicity, their race, or with that people guided by divine light, in these wars between tribes fighting to occupy the entire territory of those who share their identity, the consensus system also contemplates the extreme caricature of its reasonable dream: a world cleansed of surplus identities, peopled by real bodies endowed with properties expressed by their name. The consensus system announced a world beyond the demos, a world made up of individuals and groups simply showing common humanity. It overlooked just one thing: between individuals and humanity, there is always a partition of the perceptible, a configuration that determines the way in which the different parties have a part in the community. And there are two main modes of division: counting a part of those who have no part and not counting such a part-the demos or the ethnos. The consensus system thought its expansion was boundless: Europe, the international community, the citizenry of the world, and, finally, humanity-all so many names for a whole that is equal to the sum of its elements, each having the common property of the whole. What it discovers is a new, radical figure of the identity between all and nothing. The new figure, the nonpolitical figure of the all identical to nothing, of an integrity everywhere under attack, is also, from now on, called humanity. Man "born free and everywhere in chains" has become man born human and every where inhuman. Beyond the forms of democratic dispute, what is indeed spreading is the reign of a humanity equal to itself, directly attributed to each one, exposed in each one to its own shattering; an all inhabited by its nothingness, a humanity showing itself, demonstrating itself everywhere to be denied. The end of the great subjectifications of wrong is not the end of the age of the "universal victim"; it is, on the contrary, its beginning. The militant democracy of old went through a whole series of polemical forms of "men born free and equal in law." The various forms of "us" have taken on different subject names to try the litigious power of "human rights," to put the inscription of equality to the test, to ask if human rights, the rights of man, were more or less than the rights of the citizen, if they were those of woman, of the proletarian, of the black man and the black woman, and so on. And so "we" have given human rights all the power they could possibly have: the power of the inscription of equality amplified by the power of its rationale and its expression in the construction of litigious cases, in the linking of a world where the inscription of equality is valid and the world where it is not valid. The reign of the "humanitarian" begins, on the other hand, wherever human rights are cut off from any capacity for polemical particularization of their universality, where the egalitarian phrase ceases to be phrased, interpreted in the arguing of a wrong that manifests its litigious effectiveness. Humanity is then no longer polemically attributed to women or to proles, to blacks or to the damned of the earth. Human rights are no longer experienced as political capacities. The predicate "human" and "human rights" are simply attributed, without any phrasing, without any mediation, to their eligible party, the subject "man." The age of the "humanitarian" is one of immediate identity between the ordinary example of suffering humanity and the plenitude of the subject of humanity and of its rights. The eligible party pure and simple is then none other than the wordless victim, the ultimate figure of the one excluded from the logos, armed only with a voice expressing a monotonous moan, the moan of naked suffering, which saturation has made inaudible. More precisely, this person who is merely human then boils down to the couple of the victim, the pathetic figure of a person to whom such humanity is denied, and the executioner, the monstrous figure of a person who denies humanity. The "humanitarian" regime of the "international community" then exercises the administration of human rights in their regard, by sending supplies and medicine to the one and airborne divisions, more rarely, to the other. The transformation of the democratic stage into a humanitarian stage may be illustrated by the impossibility of any mode of enunciation. At the beginning of the May '68 movement in France, the demonstrators defined a form of subjectification summed up in a single phrase: "We are all German Jews." This phrase is a good example of the heterological mode of political subjectification: the stigmatizing phrase of the enemy, keen to track down the intruder on the stage where the classes and their parties were counted, was taken at face value, then twisted around and turned into the open subjectification of the uncounted, a name that could not possibly be confused with any real social group, with anyone's actual particulars. Obviously, a phrase of this kind would be unspeakable today for two reasons. The first is that it is not accurate: those who spoke it were not German and the majority of them were not Jewish. Since that time, the advocates of progress as well as those of law and order have decided to accept as legitimate only those claims made by real groups that take the floor in person and themselves state their own identity. No one has the right now to call themselves a prole, a black, a Jew, or a woman if they are not, if they do not possess native entitlement and the social experience. "Humanity" is, of course, the exception to this rule of authenticity; humanity's authenticity is to be speechless, its rights are back in the hands of the international community police. And this is where the second reason the phrase is now unspeakable comes in: because it is obviously indecent. Today the identity "German Jew" immediately signifies the identity of the victim of the crime against humanity that no one can claim without profanation. It is no longer a name available for political subjectification but the name of the absolute victim that suspends such subjectification. The subject of contention has become the name of what is out of bounds. The age of humanitarianism is an age where the notion of the absolute victim debars polemical games of subjectification of wrong. The episode known as the "new philosophy" is entirely summed up in this prescription: the notion of massacre stops thought in its tracks as unworthy and prohibits politics. The notion of the irredeemable then splits consensual realism: political dispute is impossible for two reasons, because its violence cripples reasonable agreement between parties and because the facetiousness of its polemical embodiments is an insult to the victims of absolute wrong. Politics must then yield before massacre, thought bow out before the unthinkable. Only, the doubling of the consensual logic of submission to the sole count of parties with the ethical/humanitarian logic of submission to the unthinkable of genocide starts to look like a double bind. The distribution of roles, it is true, may allow the two logics to be exercised separately, but only unless some provocateur comes along and lashes out at their point of intersection, a point they so obviously point to, all the while pretending not to see it. This point is the possibility of the crime against humanity's being thinkable as the entirety of extermination. This is the point where the negationist provocation strikes, turning the logic of the administrators of the possible and the thinkers of the unthinkable back on them, by wielding the twin argument of the impossibility of an exhaustive count of extermination and of its unthinkability as an idea, by asserting the impossibility of presenting the victim of the crime against humanity and of providing a sufficient reason why the executioner would have perpetrated it. This is in effect the double thrust of the negationist argument to deny the reality of the extermination of the Jews in the Nazi camps. It plays on the classic sophist paradoxes of the unending count and division ad infinitum. As early as 1950, Paul Rassinier fixed the parameters of negationism's sales pitch in the form of a series of questions whose answers let it appear every time that, even if all the elements of the process were established, their connections could never be entirely proved and still less could it be proved that they were a result of a plan entirely worked out, programmed and immanent in each of its steps. Most certainly, said Rassinier, there were Nazi proclamations advocating the extermination of all Jews. But declarations have never in themselves killed anyone. Most certainly, there were plans for gas chambers. But a plan for a gas chamber and a working gas chamber are two different things-as different as a hundred potential talers and a hundred real talers. Most certainly, there were gas chambers actually installed in a certain number of camps. But a gas chamber is only ever a gasworks that one can use for all sorts of things, and nothing about it proves that it has the specific function of mass extermination. Most certainly, there were, in all the camps, regular selections at the end of which prisoners disappeared and were never seen again. But there are thousands of ways of killing people or simply letting them die, and those who disappeared will never be able to tell us how they disappeared. Most certainly, finally, there were prisoners in the camps who were effectively gassed. But there is nothing to prove that they were the victims of a systematic overall plan and not of simple sadistic torturers. We should pause for a moment to look at the two prongs of this line of argument: Rassinier claimed in 1950 that the documents that would establish a logical connection between all these facts, linking them as one unique event, were missing. He also added that it was doubtful they would ever be found. Since then, though, documents have been found in sufficient abundance, but the revisionist provocation still has not given in. On the contrary, it has found new followers, a new level of acceptance. The more its arguments have revealed themselves to be inconsistent on the factual level, the more its real force has been shored up. This force is to damage the very system of belief according to which a series of facts is established as a singular event and as an event subsumed in the category of the possible. It is to damage the point where two possibilities must be adjusted to each other: the material possibility of the crime as a total linking of its sequences and its intellectual possibility according to its qualification as absolute crime against humanity. The negationist provocation stands up not because of the proofs it uses to oppose the accumulation of adverse proofs. It stands up because it leads each of the logics confronting each other in it to a critical point where impossibility finds itself established in one or another of its figures: as a missing link in the chain or the impossibility of thinking the link. It then forces these logics into a series of conflicting movements whereby the possible is always caught up by the impossible and verification of the event by the thought of what is unthinkable in it. The first aporia is that of the law and of the judge. French public opinion cried out against the judges who let ex-militiaman Paul Touvier off on the charge of the "crime against humanity." But before we get indignant, we should reflect on the peculiar configuration of the relationships between the law, politics, and science implied in such a matter. The juridical notion of the "crime against humanity;' initially annexed to war crimes, was freed from those to allow the pursuit of crimes that legal prescriptions and government amnesties had allowed to go unpunished. The sorry fact is that nothing by rights defines the humanity that is the object of the crime. The crime is then established not because it is recognized that humanity has been attacked in its victim, but because it is recognized that the agent who carried it out was, at the time of its execution, an underling simply obeying the collective planned will of a state "practicing a policy of ideological hegemony." The judge is then required to become a historian in order to establish the existence of such a policy, to trace the continuity from the original intention of a state to the action of one of its servants, at the risk of once again ending up in the aporias of division ad infinitum. The original judges of militiaman Touvier did not find the continuous thread of a "policy of ideological hegemony" leading from the birth of the Vichy State to the criminal act of that state's militiaman. The second lot of judges resolved the problem by making Touvier a direct subordinate of the German Nazi State. The accused argued in his defense that he showed humanity by doing less than the planned collective will required him to do. Let us suppose for a moment that an accused were to put forward conversely that he did more, that he acted without orders and without ideological motivation, out of pure personal sadism. Such an accused would be no more than an ordinary monster, escaping the legal framework of the crime against humanity, clearly revealing the impossibility of the judge's putting together the agent and the patient of the crime against humanity. This is the double catch on which the negationist argument plays. The impossibility of establishing the event of the extermination in its totality is supported by the impossibility of thinking the extermination as belonging to the reality of its time. The paradoxes that distinguish formal cause from material cause and efficient cause from final cause would have rapidly run out of steam if they merely reflected the impossibility of the four causes being able to be joined into one single sufficient principle of reason. Beyond the quibbling about the composition of the gases and the means of producing sufficient quantity, the negationist provocation calls on the "reason" of the historian in order to ask if, in their capacity as an educated person, they can find in the modes of rationality (which complex industrial and state systems in our century obey) the necessary and sufficient reason for a great modern state's abandoning itself to the designation and mass extermination of a radical enemy. The historian, who has all the facts at their fingertips ready to respond, then is caught in the trap of the notion that governs historical reasoning: for a fact to be admitted, it must be thinkable; for it to be thinkable, it must belong to what its time makes thinkable for its imputation not to be anachronistic. In a famous book, Lucien Febvre alleges that Rabelais was not a nonbeliever. 3 Not that we have any proof that he was not-that kind of truth is precisely a matter for the judge, not the historian. The truth of the historian is that Rabelais was not a nonbeliever because it was not possible for him to be, because his time did not offer the possibility of this possibility. The thought event consisting in the clear and simple position of not believing was impossible according to this particular truth: the truth of what a period in time makes thinkable, of what it authorizes the existence. To break out of this truth is to commit a mortal sin as far as the science of history goes: the sin of anachronism. How does one get from that impossibility to the impossibility that the extermination took place? Not only through the perversity of the provocateur who carries a certain reasoning to the point of absurdity and scandal, but also through the overturning of the metapolitical regime of truth. Lucien Febvre's truth was that of a sociological organicism, of the representation of society as a body governed by the homogeneity of collective attitudes and common beliefs. This solid truth has become a hollow truth. The necessary subscription of all individual thought to the common belief system of one's time has become just the hollowness of a negative ontological argument: what is not possible according to one's time is impossible. What is impossible cannot have been. The formal play of the negative ontological argument thereby chimes with the "reasonable" opinion that a great modern industrial state like Germany had no need to invent the insanity of the extermination of the Jews. The historian who has refuted all the liar's proofs cannot radically refute his lie because he cannot refute the idea of the truth that sustains it. The historian brings to the judge the connection between the facts that the judge had been missing. But, at the same time, the rationality of the historian shifts the rationality of the linking of the facts toward the rationality of their possibility. 4 It is therefore necessary for the law to outlaw the falsification of history. It is necessary, in short, for the law to do the work the historian cannot do, entrusted as they were with the job that the law cannot do. This double aporia is, of course, only the mark of the law's and of science's adherence to a certain system of belief, the system of belief peculiar to the consensus system: realism. Realism claims to be that sane attitude of mind that sticks to observable realities. It is in fact something quite different: it is the police logic of order, which asserts, in all circumstances, that it is only doing the only thing possible to do. The consensus system has absorbed the historical and objective necessity of former times, reduced to the congruous portion of the "only thing possible" that the circumstances authorize. The possible is thereby the conceptual exchanger of"reality" and "necessity:' It is also the final mode of "truth" that metapolitics perfected can offer the logic of the police order, the truth of the impossibility of the impossible. Realism is the absorption of all reality and all truth in the category of the only thing possible. In this logic, the possible/truth in all its scholarly authority is required to fill in all the holes in the possible/reality. The more unsteady the performances of managerial realism, the more it needs to legitimize itself through monotonius reiteration of the impossibility of the impossible, even if it means protecting this negative self-legitimization behind the thin barrier of the law that determines the point at which the emptiness of the truth must end, the limit that the argument of the impossibility of the impossible must not overstep. Hence the strange phenomenon of a law that outlaws the lie at a time when the law is trying to wipe out all the "taboos" that cut it off from a society itself devoted to infinite enjoyment of every sacrilege. What is at play here is not respect for the victims or holy terror but preservation of the flimsiest of secrets: the simple nullity of the impossibility of the impossible, which is the final truth of metapolitics and the ultimate legitimization of the managers of the only thing possible. More than it robs the negationists of speech, the ban rules out showing the simple emptiness of the argument of the unthinkable. There is absolutely nothing outside what is thinkable in the monstrousness of the Holocaust; nothing that goes beyond the combined capabilities of cruelty and cowardice when these benefit from all the means at the disposal of modern states; nothing these states are not capable of whenever there is a collapse in the forms of nonidentary subjectification of the count of the uncounted, wherever the democratic people is incorporated into the ethnic people. No doubt Hannah Arendt's argument of the "banality of evil" leaves us intellectually dissatisfied. It has been criticized for banalizing the overwhelming hate aimed at a specific victim. But the argument is reversible. The Jewish identity eradicated by the Nazi extermination was no different from that of ordinary anti-Semitic fantasies. So it is indeed in the capacity to put together the means of extermination that the specific difference lies. Moreover, we do not need to be intellectually satisfied here. It is not a matter of explaining genocide. Clearly the problem has been put the wrong way around. Genocide is not a topical object that today impinges on our thinking with the effect of shaking up politics and philosophy. Rather, it is governmental curbing of politics, with its remainder or its humanitarian double, that has turned genocide into a philosophical preoccupation, engaging philosophy, as ethics, to somehow deal with what in this remnant the law and science cannot get atthat identity of the human and the inhuman that the consensus state has delegated to them to worry about. And it is from this standpoint that we should locate the discussion. No "good" explanation of genocide contrasts with the bad. Ways of locating the relationship between thought and the event of genocide either enter or fail to enter into the circle of the unthinkable. The complexity of the play of this "unthinkable" is pretty well illustrated by a text of Jean-Francois Lyotard. For Lyotard, any reflection on the Holocaust must deal with the specificity of the victim, the specificity of the plan to exterminate the Jewish people as a people who have witnessed an original debt of humanity toward the Other, thought's native impotence to which Judaism bears witness and which GrecoRoman civilization has always been keen to forget. But two ways of assigning thought to the event are inextricably intertwined in his demonstration. At first the issue seems to be about the type of memory or forgetting required by the event of genocide that has come to pass. It is then a matter of measuring the consequences the notion of genocide may have for Western philosophy's reconsideration of its history, without worrying about "explaining" genocide. But the moment this history is thought of in terms of repression, the name "Jew" becomes the name of the witness of this "forgotten" of which philosophy would like to forget the necessity of forgetting. The Holocaust then finds itself assigned the "philosophical" significance of the desire to get rid of what is repressed, by eliminating the sole witness to this condition of the Other as hostage, which is initially the condition of thought. The "philosophical" identity of the victim, of the witness/hostage, then becomes the reason for the crime. It is the identity of the witness of thought's impotence that the logic of a civilization demands be forgotten. And so we have the double knot of the powerfulness of the crime and the powerlessness of thought: on the one hand, the reality of the event is once again lodged in an infinite gap between the determination of the cause and the verification of the effect, and on the other hand, the demand that it be thought becomes the very place where thought, by confronting the monstrous effects of the denial of its own impotence, locks itself into a new figure of the unthinkable. The knot established between what the event demands of thought and the thought that commanded the event then allows itself to be caught up in the circle of ethical thinking. Ethics is thinking that hyperbolizes the thought content of the crime to restore thought to the memory of its native impotence. But ethics is also thinking that tars all thought and all politics with its own impotence, by making itself the custodian of the thought of a catastrophe from which no ethics, in any case, was able to protect us. Ethics, then, is the form in which "political philosophy" turns its initial project on its head. The initial project of philosophy was to eliminate politics to achieve its true essence. With Plato, philosophy proposed to achieve itself as the basis of the community, in place of politics, and this achievement of philosophy proved, in the final analysis, to mean elimination of philosophy itself. The social science of the nineteenth century was the modern manner in which the project of the elimination/realiziation of politics was achieved as realization/elimination of philosophy. Ethics is today the final form of this realization/elimination. It is the proposition put to philosophy to eliminate itself, to leave it to the absolute Other to atone for the flaws in the notion of the Same, the crimes of philosophy "realized" as soul of the community. Ethics infinitizes the crime to infinitize the injunction that it has itself addressed by the hostage, the witness, the victim: that philosophy atone for the old pretension of philosophical mastery and the modern illusion of humanity freed from alienation, that it submit to the regime of infinite otherness that distances every subject from itself. Philosophy then becomes the reflection of the mourning that now takes on evil as well as government reduction of dikaion to sumpheron. In the name of ethics, it takes responsibility for evil, for the inhumanity of man that is the dark side of the idyll of consensus. It proposes a cure for the effacement of the political figures of otherness in the infinite otherness of the Other. It thus enlists in a perfectly determined relationship with politics-the one set out by Aristotle in the first book of Politics by separating political "humanity" from the twin figure of the stranger to the city: the subhuman or superhuman. The subhuman or superhuman is the monster or the god; it is the religious couple of the monstrous and the divine. Ethics sets thought up precisely in the face-to-face between the monster and the god/ which is to say that it takes on as its own mourning the mourning of politics. Certainly one can only approve philosophy's present concern to be modest, meaning, conscious of the combined power and powerlessness of thought, of its puny power in relation to its own immoderation. It remains to be seen how this modest thinking is to be achieved in practice, the mode in which it claims to exercise its moderation. The present modesty of the state, as we have seen, is first of all modesty in relation to politics, in other words, hyperbolization of the normal practice of the state, which is to live off the elimination of politics. We should make sure that the modesty of philosophy is not also modesty at something else's expense, that it is not the final twist of this realization/elimination of politics that "political philosophy " lives off: the mourning of politics proclaimed as expiation of the faults of"realized" philosophy. There is no mourning of politics to be reflected upon, only its present difficulty and the manner in which this difficulty forces it to adopt a specific modesty and immodesty. Politics today must be immodest in relation to the modesty forced on it by the logics of consensual management of the "only thing possible." It must be modest in relation to the domain where it has been put by the immodest modesty of ethical philosophy: the domain of the immoderate remains of modest politics, meaning, the confrontation with naked humanity and the inhumanity of the human. Political action finds itself today trapped in a pincer movement between state managerial police and the world police of humanitarianism. On the one hand, the logics of consensus systems efface the traces of political appearance, miscount, and dispute. On the other, they summon politics, driven from the scene, to set itself up from the position of a globalization of the human that is a globalization of the victim, a definition of a sense of the world and of a community of humanity based on the figure of the victim. On the one hand, they reduce the division involved in the count of the uncounted to a breakdown of groups open to presenting their identity; they locate the forms of political subjectivity within places of proximity (home, job, interest) and bonds of identity (sex, religion, race, culture). On the other, they globalize it, they exile it in the wilderness of humanity's sheer belonging to itself. They even recruit the very concern to reject the logics of consensus to imagine the basis of a non-identity-based community as being a humanity of the victim or hostage, of exile or of not belonging. But political impropriety is not not belonging. It is belonging twice over: belonging to the world of properties and parts and belonging to the improper community, to that community that egalitarian logic sets up as the part of those who have no part. And the place of its impropriety is not exile. It is not the beyond where the human, in all its nakedness, would confront itself or its other, monster and/or divinity. Politics is not the consensual community of interests that combine. But nor is it the community of some kind of being-between, of an interesse that would impose its originarity on it, the originarity of a being-incommon based on the esse (being) of the inter (between) or the inter proper to the esse.8 It is not the achievement of some more originally human humanity, to be reactivated within the mediocrity of the rule of interests or outside different disastrous embodiments. Politics' second nature is not the community's reappropriation of its original nature; it ought to be thought of effectively as second. The interesse is not the sense of community that the recapturing, in its originarity, of existence, being or "an alternative being," would deliver. The inter of a political interesse is that of an interruption or an interval. The political community is a community of interruptions, fractures, irregular and local, through which egalitarian logic comes and divides the police community from itself. It is a community of worlds in community that are intervals of subjectification: intervals constructed between identities, between spaces and places. Political being-together is a being-between: between identities, between worlds. Much as the "declaration of identity" of the accused, Blanqui, defined it, "proletarian" subjectification affirmed a community of wrong as an interval between a condition and a profession. It was the name given to beings situated between several names, several identities, several statuses: between the condition of noisy tool-wielder and the condition of speaking human being, between the condition of citizen and the condition of noncitizenship, between a definable social figure and the faceless figure of the uncounted. Political intervals are created by dividing a condition from itself. They are created by drawing a line between identities and places defined in a set place in a given world, and identities and places defined in other places and identities and places that have no place there. A political community is not the realization of a common essence or the essence of the common. It is the sharing of what is not given as being in-common: between the visible and the invisible, the near and the far, the present and the absent. This sharing assumes the construction of ties that bind the given to what is not given, the common to the private, what belongs to what does not belong. It is in this construction that common humanity argues for itself, reveals itself, and has an effect. The simple relationship between humanity and its denial never creates a community of political dispute, as current events never cease to show us. Between exposure of the inhumanity suffered by the displaced or massacred populations of Bosnia, for example, and the feeling of belonging to common humanity, compassion and goodwill are not enough to knit the ties of a political subjectification that would include, in the democratic practice of the Western metropolises, a bond with the victims of Serb aggression or with those men and women resisting it. The simple feeling of a common essence and the wrong done to it does not create politics, not even particular instances of politics that would, for example, place a bond with the raped women of Bosnia under the banner of the women's movement. The construction of wrong as a bond of community with those who do not belong to the same common remains lacking. All the bodies shown and all the living testimonies to the massacres in Bosnia do not create the bond that was once created, at the time of the Algerian War and the anticolonialist movements, by the bodies, completely hidden from view and from any examination, of the Algerians thrown in the Seine by the French police in October 1961. Around those bodies, which disappeared twice, a political bond was effectively created, made up not of identification with the victims or even with their cause but of a disidentification in relation to the "French" subject who massacred them and removed them from any count. The denial of humanity was thus constructable within the local, singular universality of a political dispute, as French citizenry's litigious relationship with itself. The feeling of injustice does not go to make up a political bond through a simple identifying that would appropriate the disappropriation of the object of wrong. In addition, there has to be the disappropriation of identity that constitutes an appropriate subject for conducting the dispute. Politics is the art of warped deductions and mixed identities. It is the art of the local and singular construction of cases of universality. Such construction is only possible as long as the singularity of the wrong-the singularity of the local argument and expression of law-is distinguished from the particularization of right attributed to collectivities according to their identity. And it is also only possible as long as its universality is separate from the naked relationship between humanity and inhumanity. The reign of globalization is not the reign of the universal. It is the opposite. It is in fact the disappearance of the places appropriate to its rationale. There is a world police and it can sometimes achieve some good. But there is no world politics. The "world" can get bigger. The universal of politics does not get any bigger. There remains the universality of the singular construction of disputes, which has no more to hope for from the newfound essence of a globalization more essentially "worldwide" than simple identification of the universal with the rule of law. We will not claim, as the "restorers" do, that politics has "simply" to find its own principle again to get back its vitality. Politics, in its specificity, is rare. It is always local and occasional. Its actual eclipse is perfectly real and no political science exists that could map its future any more than a political ethics that would make its existence the object solely of will. How some new politics could break the circle of cheerful consensuality and denial of humanity is scarcely foreseeable or decidable right now. Yet there are good reasons for thinking that it will not be able to get around the overblown promises of identity in relation to the consensual logics of the allocation of parts or the hyperbole that summons thought to a more original globalization or to a more radical experience of the inhumanity of the human. Jacques Ranciere - Disagreement (Politics and Philosophy)

by Alain Badiou

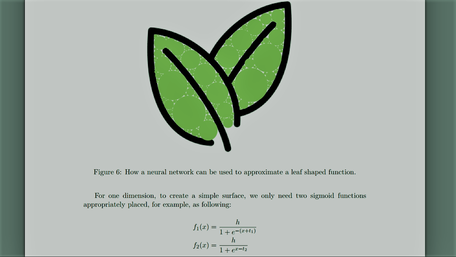

Learning from the striking novelty of the riots in the Arab countries - especially their endurance, their determination, their unarmed tenacity, their unforeseen independence - we can, I believe, first of all propose a simple definition of an historical riot: it is the result of the transformation of an immediate riot, more nihilistic than political, into a pre-political riot. The case of the Arab countries then teaches us that for this the following are required.

1 . A transition from limited localization (assemblies' attacks and destructive acts on the very site of the rebels) to the construction of an enduring central site, where the rioters install themselves in an essentially peaceful fashion, asserting that they will stay put until they receive satisfaction. Therewith we also pass from the limited and, in a sense, wasted time of the immediate riot, which is an amorphous, high-risk assault, to the extended time of the historical riot, which instead resembles old sieges of a town, except that it involves laying siege to the state. In reality, everyone knows that destruction cannot last, except in 'major wars': an immediate riot can hold out for between one and five days at the most. In its monumental site, even when surrounded and harassed by the police, or on the main avenues it ritually occupies on a set day of the week, with the crowd constantly growing, an historical riot holds out for weeks or months.

2. For that to happen there must be a transition from extension by imitation to qualitative extension. This means that all the components of the people are progressively unified on the site thus constructed: popular and student youth, obviously, but also factory workers, intellectuals of all sorts, whole families, large numbers of women, employees, civil servants, even some police officers and soldiers, and so forth. People of different religious faiths mutually protect the others' prayer times; people of conflicting origin engage in peaceful discussion as if they had always known one another. And a multiplicity of voices, absent or virtually absent from the clamour of an immediate riot, asserts itself; placards describe and demand; banners incite the crowd. Even the reactionary world press will end up referring to the 'Egyptian people' in connection with those occupyingTahrir Square. At this point the threshold of historical riot is crossed: established localization, possible l0ngue duree, intensity of compact presence, multifaceted crowd counting as the whole people. As Trotsky, who was conversant with the subject, might have said: 'The masses have mounted the stage of history.'

3. It was also necessary to make a transition from the nihilistic din of riotous attacks to the invention of a single slogan that envelops all the disparate voices: 'Mubarak, clear off!' Thus is created the possibility of a victory, since what is immediately at stake in the riot has been decided. At the antipodes of destructive desires for revenge, the movement can persist in anticipation of a specific material satisfaction: the departure of a man whose name - a short while before taboo, but now publicly condemned to ignominious erasure - is brandished.

loading...

From everything we have witnessed over the last few months let us remember the following: a riot becomes historical when its localization ceases to be limited, but grounds in the occupied space the promise of a new, long-term temporality; when its composition stops being uniform, but gradually outlines a unified representation in mosaic form of all the people; when, finally, the negative growling of pure rebellion is succeeded by the assertion of a shared demand, whose satisfaction confers an initial meaning on the word 'victory' .

In this very general framework we must stress from the outset what constitutes the specifically historical rarity of the Tunisian and Egyptian riots in early 2011: in addition to the fact that they have taught or reminded us of the laws of the transition from immediate riot to historical riot, they were fairly rapidly victorious. There you had regimes which had long seemed securely in place, which had organized non-stop police surveillance and remorselessly employed torture, which were surrounded by the solicitude of all the imperial 'democratic' powers, large or small, which were constantly oiled by corrupting manna from these powers - and here they were overthrown, or at least those who were their emblem (Ben Ali and Mubarak) were overthrown, by completely unforeseen popular action directed by no established organization. This entails that the riotous dimension of these actions is not in doubt.

Such phenomena are sufficient in themselves for us to speak of a 'rebirth of History' in connection with the riots. How many years back do we have to go to find the overthrow of a centralized, well-armed power by huge crowds with their bare hands? Thirty-two years, when the Shah ofIran, who just like Ben Ali was regarded as a Westerner and modernizer, and just like him was adored, subsidized and armed by our rulers, was overthrown by gigantic street demonstrations against which armed force was unavailing. But then we were precisely at the end of a long historical sequence when riots, wars of national liberation, revolutionary initiatives, guerrillas and youth uprisings had conferred on the idea of History its full meaning, charged as it is with sustaining and validating radical political options. Between 1950 at the earliest and 1980 at the latest, the ideas of revolution and communism were banally selfevident for masses of people throughout the world. However, a number of militants in our countries threw in the towel from the early 1970s onwards, starting down the distressing path of renegacy and rallying to the established order under the moth-eaten banner of 'anti-totalitarianism'. The Cultural Revolution in China, that Paris Commune of the epoch of socialist states,2 foundered on its own anarchic violence - was it perhaps merely a collection of immediate riots? - in 1976, with Mao's death. On their own in the world, a few groups attempted to preserve the means for a new sequence. In this sense the Iranian Revolution was terminal, not inaugural. In its obscure paradoxicality (a revolution led by an ayatollah, a popular rising embedded in a theocratic context), it heralded the end of the clear days of revolutions. In this it coincided with the working-class movement Solidarnosc in Poland. This highly significant popular uprising against a corrupt, moribund socialist state reminded us that action by the popular masses is always possible, even in a situation blasted by foreign occupation and a political regime imposed from without. Solidarnosc also reminded us that such action derives particular strength from being centred on factories and their workers. But aside from its critical force, the Polish movement remained bereft of any new idea about the country's possible destiny, and was incongruously cheered on by a future pope and an utterly reactionary clergy. Moreover, the outcome of the Iranian Revolution - the oxymoron represented by the expression 'Islamic republic' - did not, as indicated by its name, possess any universal vocation. Nor did the sad fate of the Polish state 'liberated' from communism: fanatically capitalist, xenophobic and slavishly pro-American.

Obviously, we do not know what the historical riots in Tunisia, Egypt, Syria and other Arab counties are going to lead to. We are in the initial post-riot period, and everything is uncertain. But it is clear that, unlike the Polish historical riot or the Iranian Revolution, which closed a sequence in a violent, paradoxical darkening of their ideological context, the revolts in the Arab countries are opening a sequence, by leaving their own context undecided. They are stirring up and altering historical possibilities, to the extent that the meaning which their initial victories will retrospectively assume will in large part determine the meaning of our future.

While preserving their purely even tal dimension, which is thus subtracted from 'scientific' prediction, I believe that we can inscribe these riotous tendencies as characteristic actions of what I shall call intervallic periods.

What is an intervallic period? It is what comes cifter a period in which the revolutionary conception of political action has been sufficiently clarified that, notwithstanding the ferocious internal struggles punctuating its development, it is explicitly presented as an alternative to the dominant world, and on this basis has secured massive, disciplined support. In an intervallic period, by contrast, the revolutionary idea of the preceding period, which naturally encountered formidable obstacles - relentless enemies without and a provisional inability to resolve important problems within - is dormant. It has not yet been taken up by a new sequence in its development. An open, shared and universally practicable figure of emancipation is wanting. The historical time is defined, at least for all those unamenable to selling out to domination, by a sort of uncertain interval of the Idea.

It is during such periods that the reactionaries can say, precisely because the revolutionary road is faint, even illegible, that things have resumed their natural course. Typically, this is what happened in 1815 with the restorationists of the Holy Alliance, for whom feudal social relations and their monarchical synthesis represented the sole order worthy of God, so that republican, plebeian revolution was nothing but a monstrosity encapsulated in the Terror and the diabolical figure of Robespierre. And this, typically, is what people have tried to make us believe for thirty years. We know from reliable sources (say the sanctimonious democrats and new Tartuffes) that the totalitarian aberration, lethal ideocracy, the socialist states, Marxism, Leninism, Maoism and the intellectual and practical movements that discovered the principle of their intense existence in them, were nothing but inefficient, criminal impostures, encapsulated in the diabolical figure of Stalin. The peaceful course of things - the only valid thing on offer - is the natural harmony between unbridled capitalism and impotent democracy. Impotent because servile towards the site of real power - Capital - and firmly 'controlled' when it comes to working-class and popular aspirations.

For the intervallic period we are still in, running from 1980 to 2011 (and beyond?) - a period in which classical capitalism has been revived following the collapse of the state forms of the communist road issued from the Bolshevik revolution - 'liberal democracy' is what 'liberal monarchy' was for the intervallic period when modern capitalism took off, following the crushing of the final bursts of the republican revolution (1815-50).

During these intervallic periods, however, discontent, rebellion and the conviction that the world should not be as it is, that capitalo-parliamentarianism is in no wise 'natural' , but utterly sinister -all this exists. At the same time, it cannot fmd its political form, in the first instance because it cannot draw strength from the sharing of an Idea. The force of rebellions, even when they assume an historical significance, remains essentially negative (,let them go', 'Ben Ali out', 'Mubarak clear off'). It does not deploy a slogan in the affirmative element of the Idea. That is why collective mass action can only take the form of a riot, at best directed towards its historical form, which is also called a 'mass movement' .

Let us recapitulate: the riot is the guardian of the history of emancipation in intervallic periods.

Let us return to the period 1S15-50 in France and Europe, for our own interval bears an uncanny resemblance to that Restoration. It followed the Great Revolution and, like our own last thirty years, its vertebral column was a virulent reactionary restoration, which was politically constitutionalist and economically liberal. Yet from the start of the 1830s it was a major period of riots, which were often momentarily or seemingly victorious (the 'Trois Glorieuses' of 1830, workers' riots pretty much everywhere, the 1848 'revolution', and so on). These were precisely the riots, sometimes immediate, sometimes more historical, characteristic of an intervallic period: after 1850 the republican idea, now insufficient for demarcation from bourgeois reaction, would have to be succeeded by the communist Idea.

That the awakening of History, in the form of a riot and its possible immediate victory, is not generally contemporaneous with the revival of the Idea, which would give the riot a real political future, is a very old observation. This decoupling is fully evident in some of the riots of the sans-culottes, of the bras nus, during the French Revolution itself. These riots could not make do with revolutionary ideology in its strictly republican form. They presupposed an ideological hereafter, which had not taken shape. Consequently, in the absence of any real subjective sharing of an Idea, it was impossible for them to resolve the problem of the transition from riot, albeit historical, to the consistency of an organized politics.

The inevitable lagging of riots, in as much as they are the mass sign of a reopening of History, behind the most contemporary questions of politics, themselves bequeathed by the pre-intervallic moment when there existed a broad vision of the politics of emancipation, is doubtless the most striking empirical proof of the fact that History does not contain within itself a solution to the problems it places on the agenda. However brilliant and memorable the historical riots in the Arab world, they finally come up against universal problems of politics that remained unresolved in the previous period. At the centre of these is to be found the problem of politics par excellence - namely, organization. Only, as Mao puts it, 'to have order in organization you must have it in ideology'. But ideology is only ever the set of abstract consequences of an Idea or (if you prefer) of one or several principles.

In short, guardians of the history of emancipation in an intervallic period, historical riots point to the urgency of a reformulated ideological proposal, a powerful Idea, a pivotal hypothesis, so that the energy they release and the individuals they engage can give rise, in and beyond the mass movement and the reawakening of History it signals, to a new figure of organization and hence of politics. So that the political day which follows the reawakening of History is likewise a new day. So that tomorrow is genuinely different from today. So that, in sum, the lesson contained in the last verse of a famous poem by Brecht, 'In Praise of Dialectics', is wholly valid:

Today, injustice goes with a certain stride,