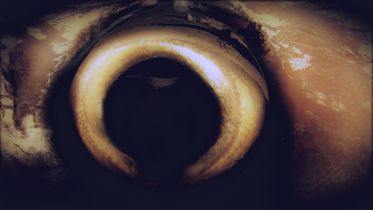

Cannibal delicacyIt is known that civilized man is characterized by an often inexplicable acuity of horror. The fear of insects is no doubt one of the most singular and most developed of these horrors as is, one is surprised to note, the fear of the eye. It seems impossible, in fact, to judge the eye using any word other than seductive, since nothing is more attractive in the bodies of animals and men. But extreme seductiveness is probably at the boundary of horror. In this respect, the eye could be related to the cutting edge, whose appearance provokes both bitter and contradictory reactions; this is what the makers of the Andalusian Dog' 1 must have hideously and obscurely experienced when, among the first images of the film, they determined the bloody loves of these two beings. That a razor would cut open the dazzling eye of a young and charming woman-this is precisely what a young man would have admired to the point of madness, a young man watched by a small cat, a young man who by chance holding in his hand a coffee spoon, suddenly wanted to take an eye in that spoon. Obviously a singular desire on the part of a white, from whom the eyes of the cows, sheep, and pigs that he eats have always been hidden. For the eye-as Stevenson exquisitely puts it, a cannibal delicacy-is, on our part, the object of such anxiety that we will never bite into it. The eye is even ranked high in horror, since it is, among other things, the eye of conscience. Victor Hugo's poem is sufficiently well known; the obsessive and lugubrious eye, the living eye, the eye that was hideously dreamed by Grandville in a nightmare he had shortly before his death2; the criminal "dreams that he has just struck down a man in a dark wood . . . Human blood has been spilled and, to use an expression that presents a ferocious image to the mind, he made an oak sweat 3. In fact, it is not a man, but a tree trunk . . , bloody , , . that thrashes and struggles , ' , under the murderous weapon. The hands of the victim are raised, pleading, but in vain. Blood continues to flow." At that point an enormous eye appears in the black sky, pursuing the criminal through space and to the bottom of the sea, where it devours him after taking the form of a fish. Innumerable eyes nevertheless multiply under the waves. On this subject, Grandville writes: "Are these the eyes of the crowd attracted by the imminent spectacle of torture?" But why would these absurd eyes be attracted, like a cloud of flies, by something so repugnant? Why as well, on the masthead of a perfectly sadistic illustrated weekly, published in Paris from 1907 to 1924, does an eye regularly appear against a red background, above a bloody spectacle? Why isn't the Eye of the Police-similar to the eye of human justice in the nightmare of Grandville-finally only the expression of a blind thirst for blood? Similar also to the eye of Crampon, condemned to death and approached by the chaplain an instant before the blade's fall: he dismissed the chaplain, but enucleated himself and gave him the happy gift of his torn-out eye, for this eye was made of glass. Notes I. This extraordinary film is the work of two young Catalans: the painter Salvador Dali, one of whose characteristic paintings we reproduce below (p. 25), and the director Luis Bunue!. See the excellent photographs published by the Cahiers d'art (July 1929, p. 230), by Bifur (August 1929, p. 105) and by Varietes (July 1929, p. 209). This film can be distinguished from banal avant-garde productions, with which one might be tempted to confuse it, in that the screenplay predominates. Several very explicit facts appear in successive order, without logical connection it is true, but penetrating so far into horror that the spectators are caught up as directly as they are in adventure films. Caught up and even precisely caught by the throat. and without artifice; do these spectators know, in fact, where they-the authors of this film, or people like them-will stop? If Bunuel himself, after the filming of the slit-open eye, remained sick for a week (he, moreover, had to film the scene of the asses' cadavers in a pestilential atmosphere), how then can one not see to what extent horror becomes fascinating, and how it alone is brutal enough to break everything that stines? 2. Victor Hugo. a reader of Le Magazin pittoresque, borrowed from the admirable written dream Crime and Expiation, and from the unprecedented drawing of Grandville, both published in 1847 (pp. 211-14), the story of the pursuit of a criminal by an obstinate eye; it is scarcely useful to observe. however, that only an obscure and sinister obsession, and not a cold memory, can explain this resemblance. We owe to Pierre d'Espezel's erudition and kindness our awareness of this curious document, probably the most beautiful of Grandville's extravagant compositions. (The poem by Victor Hugo to which Bataille refers is "La Conscience" (in the collection La Ugende des sieeles (Paris: Gallimard, Bibliotheque de la Pleiade, 1950), pp. 26-27). The poem in fact presents the eye of God following Cain. even into a (self-imposed) tomb. Tr.) 3. ["Faire suer un chene" (literally, "to make an oak sweat") is a slang expression that could be translated as "to exploit a guy" or "to rip off a guy." Tr.] excerpt from the book: Visions of Excess/Selected Writings (1927-1939)/Eye by Georges Bataille

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Steven Craig Hickman - The Intelligence of Capital: The Collapse of Politics in Contemporary Society

Steven Craig Hickman - Hyperstition: Technorevisionism – Influencing, Modifying and Updating Reality

Archives

April 2020

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed