|

by Amy Ireland

A script from the absolute unknown, how do you even begin to think about that? “Meaning” is a diversion. It evokes too much empathy. You have to ask, instead, what is a message? In the abstract? What’s the content, at the deepest, most reliable level, when you strip away all the presuppositions that you can? The basics are this. You’ve been reached by a transmission. That’s the irreducible thing. Something has been received. [And] to get in, it had to be there, already inside, waiting. Don’t you see? The process of trying to work it out — what I had thought was the way, eventually, to grasp it — to unlock the secret, it wasn’t like that. That was all wrong. It was unlocking me.1

We never find those who understand philosophers among philosophers.2

So we are confronted by a triad of mysteries: the death or otherwise of Lönnrot, the disappearance of Carter into the coffin-shaped clock, and the deliquescence of Professor Challenger as he absconds both slowly and hurriedly towards an invisible point below the strata. There is a blurry edge in all detective work that, as Borges too competently demonstrates, skirts a zig-zag threshold between apophenia and the truly canny connection of events that only appear, superficially, to be disconnected. In the name of a method that is closer to invocation than criticism, a reckless detective might refrain from determining exactly where an act of decryption lies on the ugly terrain of legitimacy and, proffering sanity as the stake, live up to the problem as it stands. The greatest puzzles are always a delicate balance of intrication and simplicity. What if a single answer were capable of resolving all three of these strange cases — blinding in its solvent consistency?

In Kant’s Critical Philosophy, Difference and Repetition, his nineteen-seventies lectures at Paris-VIII, and in a late, expanded reformulation of the preface to the first of these works (appearing in Essays Clinical and Critical), Deleuze pairs and contrasts two schemata of time: the time of the ‘revolving door’, and the time of the ‘straight labyrinth’.3 Quoting Hamlet, who furnishes the first of the four poetic formulas he will relate to the innovations of Kant’s philosophy, Deleuze writes

Time is out of joint, time is unhinged. The hinges are the axis on which the door turns. The hinge, Cardo, indicates the subordination of time to precise cardinal points, through which the periodic movements it measures pass. As long as time remains on its hinges, it is subordinated to extensive movement; it is the measure of movement, its interval or number. This characteristic of ancient philosophy has often been emphasised: the subordination of time to the circular movement of the world as the turning Door, a revolving door, a labyrinth opening onto its eternal origin. [C’est la porte-tambour, le labyrinthe ouverte sur l’origine éternelle.]

Time out of joint, the door off its hinges, signifies the first great Kantian reversal: movement is now subordinated to time. Time is no longer related to the movement it measures, but rather movement to the time that conditions it. Moreover, movement is no longer the determination of objects, but the description of a space, a space we must set aside in order to discover time as the condition of action. Time thus becomes unilinear and rectilinear, no longer in the sense that it would measure a derived movement, but in and through itself, insofar as it imposes the succession of its determination on every possible movement. This is a rectification of time. Time ceases to be curved by a God who makes it depend on movement. It ceases to be cardinal and becomes ordinal, the order of an empty time. […] The labyrinth takes on a new look — neither a circle nor a spiral, but a thread, a pure straight line, all the more mysterious in that it is simple, inexorable, terrible — “the labyrinth made of a single straight line which is indivisible, incessant”.4

The contrast between these two figures is due, first and foremost, to the relationship between time and movement they express. In the schema of the revolving door, time is twice subordinated: first, to a transcendent eternity which provides the rational model for the ordering of movement, and second, to the rationally-ordered movement from which time’s number is derived (the aperture ‘onto the eternal origin’ constituted by the resonance of copy with model). In the schema of the straight labyrinth, movement is subordinated to time, which conditions movement, inaugurating a reversal of priority between the two and a shift from a spatialised classification of the difference to a temporal one.5 The pairing of the two figures is more enigmatic. Since the former reappears as a functional attribute of the particle-clock (“the assemblage serving as a revolving door” [l’agencement qui servait comme d’une porte-tambour]), that strange vehicle which facilitates the disappearances of Carter and Challenger in “Through the Gates of the Silver Key” and “The Geology of Morals”, and the latter clearly invokes the straight labyrinth (“the labyrinth made of a single straight line which is indivisible, incessant”) used by Lönnrot to riddle Sharlach in the confrontation at the Villa Triste-le-Roy, both seem to conceal passageways by which escape from specific geometrical tyrannies — indexed here by extensity, cardinality, and ‘a space we must set aside’ — may be effectuated.6However, given the fact that the revolving door seems to implement the geometrical conditions it somehow also affords an exit from, and the obvious preference Deleuze (as a transcendental philosopher) exhibits for the straight labyrinth as a ‘rectification’ of time, the counterintuitive nature of this proposition is not easily brushed aside. Deeper exploration is required.

Revolving Door I: The Time of Philosophers and Theologians

In the history of Western philosophy, the revolving door is the archetypal image of pre-critical temporality. It takes its coordinates first from astronomical movements, and then from terrestrial ones: the rotation of planets and seasons.7 These revolutions, confining time to motion and phenomenality, are held in contrast to what is outside them and what has been said to have engendered them — an ever-present but non-manifest, spatiotemporally unconditioned, unified mind or essence. In his lectures, Deleuze links this figure of time, curved by the hand of a god, to “the arc of the demiurge which makes circles” in the account given by Plato’s Timaeus.8

Since the model was an ever-living being, [the demiurge] undertook to make this universe of ours the same as well, or as similar as it could be. But the being that served as the model was eternal, and it was impossible for him to make this altogether an attribute of any created object. Nevertheless, he determined to make it a kind of moving likeness of eternity, and so in the very act of ordering the universe he created a likeness of eternity, a likeness that progresses eternally through the sequence of numbers, while eternity abides in oneness.9

Timaeus, an expert astronomer who has “specialised in natural science” refers several times to his cosmogony as an ἐικός λόγος (a ‘likely account’), a play on words drawing on the relation between εἰκόνες and ἐικός meant to reinforce the notion of the cosmos as a likeness — the imperfect copy of a perfect original.10 Here, worldly imperfection is due to the changeability of the contents of the copy, which unlike their eternal origin, are subject to time:

This image of eternity is what we have come to call ‘time’, since along with the creation of the universe [the demiurge] devised and created days, nights, months, and years, which did not exist before the creation of the universe. They are all parts of time, and ‘was’ and ‘will be’ are created aspects of time which we thoughtlessly and mistakenly apply to that which is eternal. For we say that it was, is, and will be, when in fact only ‘is’ truly belongs to it, while ‘was’ and ‘will be’ are properties of things that are created and that change over time, since ‘was’ and ‘will be’ are both changes. What is for ever consistent and unchanging, however, does not have the property of becoming older or younger with the passage of time; it was not created at some point, it has not come into existence just now, and it will not be created in the future. As a rule, in fact, none of the modifications that belong to the things that move about in the sensible world, as a result of having been created, should be attributed to it; they are aspects of time as it imitates eternity and cycles through the numbers.11

There is no measurable time prior to the demiurge’s imposition of order on a previously disordered cosmos, composed only of confused matter and erratic motion. Because time arises from movement, only a perfectly regular and harmonious totality of cosmic motion will install temporality in the rational manner required to produce a sufficiently faithful copy of the model. This imposition of formal regularity is not, however, without complication. Deleuze’s emphasis on the motif of circularity arises from the description, first, of the demiurge ensuring that the matter of the universe is “perfectly spherical, equidistant in all directions from its centre to the extremes”, “freeing” its primary motion from imbalance by giving it a “circular movement … setting it spinning at a constant pace in the same place and within itself”, and then, with the totality of the matter of the universe thus arranged, of the inauguration of a complex process of division and mixing for the purpose of imbuing the assemblage with a soul, which the demiurge creates via the combination of two media: the “indivisible and never changing”, and the “divided and created substance of the physical world” (the former indexing identity, the latter, difference) obtaining a third medium with aspects of both, thus allowing for a flow of information between the formal and the phenomenal.12

He then blends the indivisible with the divisible and the alloy of the indivisible and divisible, fashioning from the tripartite mixture a homogenous whole, but not without effort, for “getting difference to be compatible with identity [takes] force, since difference does not readily form mixtures”.13 Despite the complexity, might and skill brought to the work of ordering by the demiurge (who is a craftsman, after all), a material remainder — what Deleuze will call “the unequal in itself” — still persists, and further blending is required.14 This involves a tortured series of intervallic material distributions from which the demiurge finally extracts an obedient harmony.15 The mixture is then split into strips, laid out like an X and folded together into two revolving circles, the outer circle — containing “the equal in the form of the movement of the Same” — revolves with the primary movement of the cosmos and is justly named “the revolution of identity” while the inner circle — revolving at an angle to the circle of identity — contains the eight then-known “planets” (including the sun and the moon) along with “what subsists of inequality in the divisible” by distributing it among the planetary orbits, and bears the denomination “the revolution of difference”.16 This latter grounds the derivation of time. The Great Symmetrical Cycle

Because it is “the shared task” of the heavenly bodies “to produce time”, a considerable portion of the “Timaeus” is dedicated to a geometrical description of planetary ambulation, offering precise calculations of each planet’s orbit which, when taken together, add up to an internally and externally harmonious totality (each orbit internally relative to the others, and the whole externally relative to the revolution of the circle of identity): the world’s year.17 This single, great revolution yields “the perfect number of time” and is marked by the “moment when all the eight revolutions, with their relative speeds, attain completion and regain their starting points”, resetting the cycle of the circle of difference in relation to the circle of identity.18 Pre-critical time is thus simply the organisation and rationalisation of a prior, chaotic, spatiality in response to the exigencies of a divine model which exists both outside space and time. A great compass, dividing a cosmic sphere into equal and predictable portions, priming its matter for technological and cultural capture: the seasonal arithmetic that will come to ground agriculture; the compartmentalisation of the day, the week and the year into periods devoted alternatively to the sacred or the profane; the striations of latitude facilitating oceanic navigation, cartography, imperialism, and the proportional fastidiousness of classical architecture and art.

An exclusive disjunction (the abiding feature of monotheistic religion) administrates the distinction between eternity and the cosmos as the ordered structure of secondary appearances. Held apart from the eternal and locked down by matter and movement, this turning according to number is only an auxiliary, fallen ‘image’. A simulation generated and managed by a fully exteriorised and transcendent non-time, which functions as the ultimate measure against which every determinate object falls into a static and immutable hierarchical series whose order can never be shifted, interrogated, or affected by feedback from within. Because it continues to be tethered to a transcendent realm which imposes teleological order, the most generous aberration allowed to time — one “marked by material, meteorological and terrestrial contingencies” — still remains derivative of movement.19 ‘Time’ beyond revolution is transcendent, tenseless, authoritative and persistent. The revolving door is therefore a dualistic image of temporality, inserting a gap between the hierarchically organised, oppositional qualities of idea and appearance; unity and variation; identity and difference; indivisibility and divisibility; being and becoming, good and evil, inside and outside — its borders stalked by the constabulary of the laws of thought, and god. It is, as Luce Irigaray tirelessly anatomises in “Plato’s Hystera”, the time — as space — of the Platonic cave, a “theatrical trick” designed to inaugurate the great “circus” of representation via the circular repetition of the same. The cave’s anterior tunnel leads upward into the light.

Upward — this notation indicates from the very start that the Platonic cave functions as an attempt to give an orientation to the reproduction and representation of something that is always already there. […] The orientation functions by turning everything over, by reversing, and by pivoting around axes of symmetry..20

The cardinal points of the compass, or four wings of the door’s turning hinge, exhibit the spatialisation of time inherent to the image. The law of its number is cardinality — quantitative measurement of internally homogenous content — and a representational form of numeracy. Being a sphere, it is intrinsically symmetrical. In this way, space and time are confined to the double homogeneity of extension and simultaneity — to the circus of representational reproduction and its clowns, whose comedy is always enacted in the mode of farce, a repetition that always “falls short” of its model.21There are, therefore, only “proportions, functions, [and] relations” available inside the simulation that can be referred “back to sameness”.22 And this sameness is at once the model for the beautiful, the truthful, and the good — astronomical rationality providing the exemplar for human aesthetic, epistemological and moral order.

Truth

Man, as a rational animal equipped with the ability to observe and understand these relations, is ontologically at home in the universe of the revolving door. Human cognition and sensibility, when exercised correctly, are perfectly resonant with the structure of phenomena. Thought thus naturally inclines towards the law that the demiurge embodies and by extension, to the model from which the universe has been copied. Psychology, cosmology and rationality are bound in cosmic rhyme. This is precisely what the latter part of the Timaeus then turns to, linking the account it has just given of human perception, especially that of sight, to our ability to infer the universal law of the good, the beautiful, and the true, and to reproduce it on a microcosmic level, specifically through the practice of philosophy.23 Plato’s cosmos is teleologically assured by the perfection of the demiurge, and opposes both accounts of cosmogenesis more sympathetic to contingency, chance and natural selection (such as those of Empedocles, Leucippus and Democritus, which offer explanations exhibiting an awkward but prescient Darwinism) and the immanent teleology of Aristotle. Revolution thus has a moral content, and Timaeus concludes his account of cosmogenesis by stating that,

since the movements that are naturally akin to our divine part are the thoughts and revolutions of the universe, these are what each of us should be guided by as we attempt to reverse the corruption of the circuits in our heads, that happened around the time of our birth, by studying the harmonies and revolutions of the universe.24

In this way, “we will restore our nature to its original condition” achieving “our goal” of living “now and in the future, the best life that the gods have placed within human reach”.25 The importance of sight to the practice of philosophy is insisted upon here because it alone of all the senses provides us with access to the law of number (and by extension, a model of perfect morality) embedded in the rotations of the planets.26 Vision is thus the most morally-attuned sense, the conduit of goodness and beauty, and the base upon which one can realise the latent harmoniousness of one’s own relation to the universe. These ‘corrupt circuits’ in need of correction reprise the wandering of the planets prior to the ordering of their movements by the demiurge, and not insignificantly, ‘wanderer’ (πλάνης), ‘illusion’, ‘deceit’ or ‘discursivity’ (πλάνη) and ‘planet’ (πλάνητας ἀστήρ — wandering star) all share a similar root in ancient Greek, with Plato using the term ‘planomenon’ (πλανόμενον) elsewhere to mean ‘errant’.27 Truth emerges in inverse proportion to the itinerant dithyramb of material insubordination. Timaeus completes the moral lesson of cardinality, vision and aspirational goodness with a warning. Men who live “unmanly or immoral lives” are destined to fall farther down the series of good and perfect beings in harmony with the order of the universe, being “reborn in their next incarnation as women”.28

The return to sameness, finally, ensures that the universe will not degrade or dissolve of its own accord. While “the model exists for all eternity”, “the universe was and is and always will be for all time”, unless the demiurge explicitly wishes it to be so (“anything created by me is imperishable unless I will it”); so long as the world remains in harmony, this dissolution will not occur — a threat monotheism will make much of in the epochs to come.29 Hence the biblical prophecies of apocalypse such as that which suggests that when the day arrives, the heavens will depart “as a scroll when it is rolled together”, inflected back into the curved palm of its god.30 Broadened beyond its exemplary delineation in the “Timaeus”, the revolving door thus becomes a cipher for temporal dualisms in general. Truth is located in a lost transcendence (the indivisible, god, eternity), obtainable only at a delay via religion or via the work of philosophical contemplation shepherded by vision — the decanting of a priori knowledge from empirical experience, which prior to Kant, denoted a separate and transcendent ideality. If there is knowledge of this fallenness and of the perfection of that other realm inside that of the world of motion and change, this can only be so because ‘man’ is made in the image of a god, or has forgotten something he once knew.31 Thought is inherently linked with its ground via an internal isomorphism — a rhyme — acting as the guarantor of its intuitions of damnation and error, whose causes are always external. Its correlative subject is moral or epistemological: the theologian or the philosopher, compelled to discover the realm of essences behind the veil of appearances. There is, as there always is, a sexual difference attached to the dualism. Historically, the material, fallen aspect of time-as-variation is feminised, secondary, and passive. Timaeus calls it the “receptacle”, “the mother”, “the nurse and the nurturer of the universe” and characterises it via all the emblems of lack: it is “altogether characterless”, a bare medium for the production of formed elements; passive (“it only ever acts as the receptacle for everything”); it operates through mimicry (“[i]ts nature is to … be modified and altered by the things that enter it, with the result that it appears different at different times”) having no nature of its own, and is “difficult” and “obscure”, while the creative force untouched by temporality — that which energises representation as a condition of the feminised matter it circumscribes — is primary, active, de-substantialised, and masculine.32 “It would not be out of place to compare the receptacle to a mother, the source to a father, and what they create between them to a child.”33 Is there a neater epithet to describe the age-old pact between reproduction and representation? Sensible, material, and bound in harmonious relation to a transcendent non-time, pre-critical temporality is irrevocably secondary and modal. The time of the revolving door is a mode of eternity, the essential structure of which appears to us as a succession of moments — extensive, cardinal, homogenous — arranged in a cyclical repetition of the same, with a spatial line delimiting outside from inside.34 As Deleuze puts it, “all the time of antiquity is marked by a modal character … time is a mode and not a being, no more than number is a being. Number is a mode in relation to what it quantifies, in the same way that time is a mode in relation to what it measures”.35 In a world for which time is a mere, cardinalised image of the eternal, held apart from it in a relation of exclusive disjunction, administered by a god, all experience is that of a subject condemned to reckon, neurotically, with its originary imperfection. The great line demarcating outside from inside assigns interiority to time and exteriority to the non-time of eternity via a spatial horizon. A definitionally beautiful misconception of the topology of time, but a misconception nonetheless.36 Straight Labyrinth I: The Time of Economists and Poets

The circle must be abandoned as a faulty principle of return; we must abandon our tendency to organize everything into a sphere. All things return on the straight and narrow by way of a straight and labyrinthine line.37

‘Rectifying’ the celestial or meteorological temporality of the revolving door, the figure of time expressed in the straight labyrinth emerges in Deleuze’s various accounts as “the time of the city” and also that of the “desert”.38 The subordination of time to space and motion dissolves into the contentless, temporal determination of the empirical by an immanent yet abstract process. Deleuze notes that Kant was able to apprehend this due to his historical and geographical situation — virtually immobilised in his Königsberg study, yet sensitive to subterranean tremors — deep in the heart of Europe during the ignition of modern industrialisation. There is an embedded double reference to capitalist temporality, brought to light by Marx’s statement in the Grundrisse, that

Capital by its nature drives beyond every spatial barrier. Thus the creation of the physical conditions of exchange — of the means of communication and transport — the annihilation of space by time -- becomes an extraordinary necessity for it …

and to Friedrich Hölderlin’s “Notes on the Oedipus”, leading Deleuze to state that “it is correct to claim that neither Fichte nor Hegel is the descendent of Kant — rather it is Hölderlin, who discovers the emptiness of pure time”.39 If the industrial city is also a desert, it is the Athenian desert of the Sophoclean tragedies, for, as Hölderlin writes, Oedipus is remarkable in its uniquely modern conception of the genre, in which “God and man communicate in the all-forgetting form of unfaithfulness”.40 Oedipus, like the subject of the First Critique,

forgets both himself and the God and, in a sacred manner, of course, turns himself round like a traitor. For at the most extreme edge of suffering, nothing exists beside the conditions of time or space. Man forgets himself there because he is wholly in the moment; and God, because he is nothing else than time. And both are unfaithful: time, because at such a moment it reverses categorically — beginning and end simply cannot be connected; and man, because at this moment he must follow the categorical reversal, and therefore simply cannot be in the following what he was in the beginning.41

Hölderlin’s identification of a ‘categorical reversal’ in the dual turning-away of god and man is taken up by Deleuze as the mark that indicates a historical transition in the schemata of time, and in turn, the relation this reversal installs between the two sides of the disjunctive couple. With the figure of Oedipus, the initial shift from the temporality of the revolving door to that of the straight labyrinth is consecrated, and — following Hölderlin’s interpretation — coincides with a truly modern sense of time, a time that is inherently tragic, but in an unprecedented way. While Plato’s arc of integrated planetary motion is always returning — like the great cyclical tragedies of Aeschylus — to a state of equilibrium, ending where it began, Hölderlin’s Oedipus is “traversed by a straight line which tears him along” with “murderous slowness” towards an enigmatic dissolution at an unknown coordinate in the shifting desert sands: and “Towards what? Nothing”.42 The distinction between ancient and modern tragic forms — and elsewhere, between farce and tragedy — is determined by the placement of the limit with which the hero interacts. In the ancient conception of the genre, tragedy conforms to the exclusive disjunction operating under the aegis of the gods. The limit with which the hero comes into conflict is external, manifested in a law that is then transgressed by some excessive act for which the hero must atone, triggering a return to order.43 Deleuze sees in this cycle of limit, transgression and return, a perfect isomorphism with the schema of the revolving door.

[T]his tragic time is modelled on astronomical time since in astronomical time you have the sphere of fixed points which is precisely the sphere of perfect limitation, you have the planets and the movements of the planets which, in a certain way, break through the limit, then you have the atonement, which is to say the re-establishment of justice since the planets find themselves in the same position again.44

The cycle is reinforced by the act of transgression, harmony is reinstated between the realm of the gods and the realm of men, and we know in advance the lesson that will be learned.45 But something different happens for Oedipus. The limit he encounters is no longer external, having shifted simultaneously closer and further away — the threshold dividing gods from men, and time from space, is both interior to Oedipus and beyond him — it has become “enigmatic”.46 It cleaves him in two and drives him towards an infinity that rises up to meet him in an “all-forgetting form of unfaithfulness”, annihilating him at Colonus whilst looping him back upon himself.47 Following Hölderlin’s idiosyncratic, Kantian reading of the text, the Sophoclean tragedy is condensed into an infernal play of diversion and re-orientation as Oedipus is forced to confront himself in the form of an infinite self-displacing horizon which draws him across the deflated denouement of King Oedipus and into the relentless modern desert of Oedipus at Colonus.48

Oedipus’ time is no longer the cyclical time of return to a founding order, but a simple, straight line which complicates everything. The limit manifests both as a temporal fracture interior to Oedipus’ vexed subjectivity and a point to which he tends — “the gap of an in-between, which occasions, finally, a loss of self”.49 There is no atonement for Oedipus, although there is a tribunal — and a crime. He is not subject to a hero’s death, only a long and desolate exile (a little too long to be comfortable) to which he voluntarily submits in the absence of divine directive.50 Thus Oedipus “turns himself round like a traitor”, but in a sacred manner — the trial becoming what Jean Beaufret (the Hölderlin commentator Deleuze draws most visibly on besides a few cursory gestures towards Heidegger, who he cites laconically in Difference and Repetition and the lectures on Kant), names both a “heresy” and an “initiation” — and is “returned to himself” in two ways.51 First, in terms of the mythic narrative, as the cause of himself (Oedipus is the cause of the plague that causes Oedipus) and more enigmatically at the terminus of his abstractly interminable wanderings, where he ‘returns’ in such a way that he can no longer be what he was in the beginning. When the god who “is nothing more than time”, finally, and not without an irony that is unique to Hölderlin’s translation (“Why are we delaying? Let’s go! You are too slow!”), enables his demise, we are denied the catharsis that typically accompanies the spectacle of the hero’s death.52 “What happened?” implores the chorus of the small party that has accompanied Oedipus to the threshold beyond which only he and Theseus are allowed to pass.53 The response is a brief and integrally obscure report.54 It is speculated that Oedipus has vanished into “the earth’s foundations” which “gently opened up and received him with no pain” or was “lifted away to the far dark shore” by “a swift invisible hand”, the prolonged arrival of his death heralded by thunder and strange surges of lightning, illuminating, briefly, the hidden diagonal that haunts the in-between of sky and ground, the realm of the gods and the realm of men.55 In the cracks of the Kantian machinery a different disjunction momentarily rears its faceless mien, whilst at the end of the line, “death loses itself in itself” and Oedipus, “having nothing left to hide” becomes “the guardian of a secret”.56 Between these two returns, the modern tragic figure is split across time both intensively and extensively as its own internal and external limit and source. The Sophoclean line does not restore a temporality of lost equilibrium, as is the rule in classical tragedy, but ends unresolved, internally perturbed, and terminally out of balance. Shamanic Oedipus

Oedipus plays an ambivalent role in Deleuze’s writing. Like the shaman and the despot he is always double.57 Carlo Ginzberg makes the connection between shamanic practices and the Oedipus myth explicit in Ecstasies — his trans-temporal, trans-spatial study of the witches’ sabbath — where he finds in the motif of the swollen foot (which gives Oedipus his name) the mytho-cultural stamp of the shamanic initiate whose journey leads inexorably to the realm of the dead.58 Oedipus incarnates, as such, the mythical archetype of the dying god, which links him enigmatically with Christ and Dionysus.59 Moreover, the persistence of lameness, monosandalism, bodily maiming, or an unbalanced gait among the vast swathe of myths and cultural practices included in Ginzberg’s study reveals a fundamental trait attributable to all beings who, like Oedipus, are “suspended between the realm of the dead and the realm of the living”: “Anyone who goes to or returns from the nether world — man, animal, or a mixture of the two — is marked by an asymmetry.”60 This asymmetry, at once abstract and empirical, is measured against a perceived natural symmetry that keeps the social realm in harmony with the circular world of revolving seasons and astronomical cycles — coordinates that return the cycle to its beginning. “The trans-cultural diffusion of myths and rituals revolving around physiological asymmetry”, writes Ginzberg, “most probably sinks its psychological roots in this minimal, elementary perception that the human species has of itself”, namely the “recognition of symmetry as a characteristic of human beings”. Thus, “[a]nything that modifies this image on a literary or metaphorical plane therefore seems particularly suited to express an experience that exceeds the limits of what is human”.61 Mythical lameness symbolises an otherworldly incursion, a problematic asymmetry that intrudes upon a so-called natural humanity and opens a passage between worlds.

Ginzberg also notes in passing (although only to point out what he considers a superficial reading indebted to an overly synchronic methodology) Levi-Strauss’ connection of symbolic lameness to the passage of the seasons, where it features as part of a dance-based ritual performed to truncate a particular season and accelerate the passage to the next, offering a “perfect diagram” of the hoped-for imbalance.62 If Ginzberg is warranted in discounting Levi-Strauss’ hypothesis, perhaps this is not because it is wholly incorrect so much as an interpretation that is limited insofar as it remains indebted to a particular conception of time among its proponents. Ritual or symbolic lameness grasped as a spell for accelerating the seasonal series acts as a superficial interpretation covering over a deeper one, operating within an altogether different understanding of time. One glimpsed beneath the esotericism of Deleuze’s statement that the “ego is a mask for other masks, a disguise under other disguises. Indistinguishable from its own clowns, it walks with a limp on one green leg and one red leg”.63 Read through these subterranean lines which knit it into a complex cultural history of shamanic tropes and practices, Oedipus’ swollen foot condenses time compression, an initiation preceding a journey to the realm of the dead and a fundamental disequilibrium, and thereby acts as a cipher for the key aspects of the Sophoclean tragedy in Hölderlin’s interpretation and the schematic shift from the revolving door to the straight labyrinth. In “Notes on the Oedipus” and “Notes on the Antigone”, Hölderlin proposes a reading that can be extrapolated from a “calculable law” opposing a discursive logic embedded in history, judgement and the mundane affairs of the human world, with an obscure notion of rhythm.64 The idiosyncrasy of his reading arises from an attempt to affirm the realist paradigm (grounded in scientific and historical validity) that dominated early German Romanticism alongside an unnameable and unrepresentable “efficacity”, located in “another dimension […] beyond and below” conceptual thought, which he believed characterised the tragic in its essence.65 The aim of the law was to make this obscure element momentarily graspable — not as something represented, but as the form of representation itself — a momentary “inspiration” that “comprehends itself infinitely … in a consciousness which cancels out consciousness”.66 As Beaufret frequently reminds his readers, the influence of Kant on the young poet is difficult to miss, and is particularly apparent when Hölderlin writes, for example, “[a]mong men, one must above all bear in mind that every thing is something, i.e. that it is cognisable in the medium of its appearance, and that the manner in which it is defined can be determined and taught”.67 Applied to the two Oedipus plays, taken together as a single drama, this yields an analysis in which a rhythmic distribution of the dialogue becomes diagrammable as a speed differential broken by a caesura corresponding to the prophecy of Tiresias. In contrast to Antigone where the structure is inverted (Tiresias’ prophecy being withheld until the end), the caesura in the Oedipus plays occurs early in the drama, countering a momentum which “inclines … from the end towards the beginning”.68

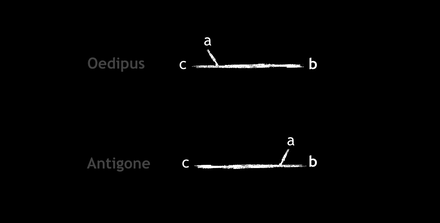

Hölderlin’s rhythmic diagrams of Oedipus and Antigone. Note that the notational progression from a (caesura), to b(end), and c (beginning) implies that the caesura is logically prior to the two points given in successive time.

By the time Tiresias speaks the “pure word” that reveals to Oedipus the truth of his identity everything of significance has already taken place, and the drama is supplied by Oedipus’ apprehension and acceptance of his fate, dragged along by the line of time, in which he learns to become who he is by becoming something else (as the cause of himself he is also the cause of a difference from himself).69The narrative is, incidentally, structured like a modern detective story, in which one begins by asking ‘What happened?’.70 The caesura breaks the consistency of Oedipus’ conception of himself, rewrites his memories (“the killer you are seeking is yourself”), and throws him into a time that suddenly becomes animate with a ‘before’ that was not previously available, and ‘after’ that sutures him to zero: “This day brings your birth; and brings your death”.71 The terrible implication of his fate — the prophecy of patricide and incest that lead his parents to desert him as an infant, supposedly left to die among the elements, and the discovery that everything he had done to avoid it has in fact functioned to bring it about — rises up before him. The ground falls away and, as Hölderlin writes, the rhythmic structure of the text propels Oedipus backwards towards his beginning with an incredible momentum, simultaneously interminable, due to the indifference of the gods, whilst slowly hurrying him towards his death. It is not for nothing that Hölderlin would pronounce in a letter to a friend that “[t]he true meaning of tragedy is most easily grasped from the position of paradox”.72 The caesura shields the first portion of the two Oedipus plays from their accelerated second portion, interfacing the differential speeds of dramatic action, and in this, wordlessly renders Hölderlin’s idea of an otherworldly efficacity rhythmically apprehensible without representing it.73 The operational rule of this manifestation is disequilibrium or asymmetry, and asymmetry linearly breaks the foundational rhyme that animates the Timaean cosmos, and inaugurates a new rule, the shamanic limp of schizophrenic auto-production. Oedipus’s initiation is a countdown that re-initiates his fatal loop.

The caesura thus produces two ‘times’ — an asymmetrical, looped, auto-productive time (one slice of which is rhythmically compressed, generating an empirical acceleration), and the asymmetrical form of time productive of asymmetrical time (Hölderlin’s modern god) — and two deaths: the horizontal death at the end of straight line, which takes Oedipus into the ground, and the secret, vertical death of the caesura, which rearranges everything in a single instant, producing and grounding the physical death of Oedipus and the time it takes place in. Hölderlin will denote both with the mathematical expression “= 0”.74 In contrast to the progressive time of the heretic’s trial, “the ever-oppositional dialogue”, the history and affairs of Thebes, and Oedipus’ voyage of metamorphosis “in which the beginning and end no longer rhyme”, the caesura is the irruption of time as a void which produces succession and abides within Oedipus in the function of an initiation as he travels the line that will remove him “from his orbit of life … to another world, [to] the eccentric orbit of the dead”.75 It is, to borrow a term from MVU’s resident Hyper-Kantian, R. E. Templeton, a “transcendental occurrence”.76 Split across an asymmetrical empirical succession and a far more obscure asymmetry that both grounds and ungrounds it, time indeed becomes a straight line with a subterranean labyrinth as its premise. A strange kind of homogeneity forged in war. With the shifting of the limit — the great rift that draws a threshold between two worlds, defining inside and outside — into the modern Oedipal subject, everything changes. When Hölderlin claims that in the double betrayal of man and god, “infinite unification purifies itself through infinite separation”, purification is no longer just a euphemism for catharsis but the precise characterisation of this pure and empty form of time.77 Anglossic qabbala distils this insight with economic clarity: Kant is a break and a link.

“Rather than being concerned with what happens before and after Kant (which amounts to the same thing)”, writes Deleuze,

we should be concerned with a precise moment within Kantianism, a furtive and explosive moment which is not even continued by Kant, much less by post-Kantianism — except, perhaps, by Hölderlin in the experience and the idea of a ‘categorical reversal’. For when Kant puts rational theology into question, in the same stroke he introduces a kind of disequilibrium, a fissure or crack in the pure Self of the ‘I think’, an alienation in principle, insurmountable in principle: the subject can henceforth represent its own spontaneity only as that of an Other, and in so doing invoke a mysterious coherence in the last instance which excludes its own — namely, that of the world and God. A Cogito for a dissolved Self: the Self of ‘I think’ includes in its essence a receptivity of intuition in relation to which I is already an other. It matters little that synthetic identity — and, following that, the morality of practical reason — restore the integrity of the self, of the world and of God, thereby preparing the way for post-Kantian syntheses: for a brief moment we enter into that schizophrenia in principle which characterises the highest power of thought, and opens Being directly on to difference, despite all the mediations, all the reconciliations, of the concept.78

There are three elements to this ‘furtive and explosive’ moment in Kant: the death of God, the fractured I, and the passive nature of the empirical self, all of which correspond to the introduction of transcendental time into the subject and usher in an immense complication of what we take to be human agency.

The death of god is the effacement of the demiurge, along with the essences from which he constructs the phenomenal world of appearance. Without this god, what guarantees the faithful reproduction within the image-simulation of reality of its eternal model? How can we know our experience rhymes with its ground? This leads to an ontological problem whereby ‘man’, the plaything of empirical time, can no longer assume ‘he’ is at home in the world of experience. If there is to be a disjunction between law and its material manifestation, who, if not god, administers it? Nothing is there to underwrite the Platonic values of truth, goodness and beauty, and the modern, empirical subject finds itself at sea in a murderous asymmetry that promises nothing but the cosmic fatigue of ultimate extinquishment under the second law of thermodynamics. The fractured I is even more insidious. The subject, no longer infirm and fallen, as it is for Plato, is constitutive, but “constantly hollow[ed] out”, spilt “in two” and “double[d]”, alienated from itself across the form of time in such a way that it cannot experience its constitutive power.79 Worse, as Rimbaud so acutely put it — “It is false to say: I think; one ought to say I am thought … I is another” — that shard of self, the empirical ego which registers phenomena, cannot know what its double is and must now contend with its new status of integral receptivity.80 How, then, does it believe itself to act rather than simply be acted-through? On what does it found its ethics and its politics? This is the initiatory consequence of the transcendental philosophy of time. The transition from the revolving door dramatises the modulation from transcendent to transcendental distinction, reconfigures the a priori, isolated notion of eternity, and moves time from a spatially subsumed cardinality to a purely formal ordinality — in which distance between numbers opens onto the realm of depth. Philosophy, of course, has preliminary solutions to all of these problems, but in solving them, it steals intermittently back and forth between schemata, recuperating certain comforts native to the time of the revolving door, and smuggling a dying theology into the explosive zones of the city and the desert. Initiation (Tragedy)

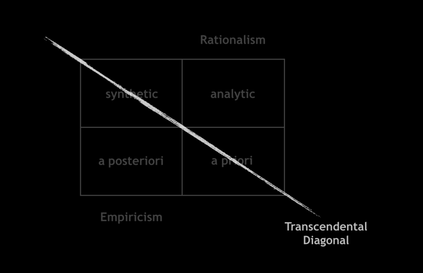

The straight line is the shortest path between two points. This is the example Deleuze uses to explain Kant’s development of a priori synthetic judgements, those “prodigious monsters” that overcome the historical a priori / analytic, a posteriori / synthetic dualism — “the death of sound philosophy” — targeted by the First Critique.81 The straight line is thus also a diagonal one, and in this sense, the leanest diagram of critique. The first, faint sketch of a philosophy erected out of paradox.

The Lovecraftian machinery of the text follows from this primary opposition between synthetic sense experience and analytic logic by reformatting it into a division between sensibility and understanding and locating both within the bounds of the a priori on a transcendental diagonal.82

Receptive, presentational and constitutive, sensibility furnishes the a priori forms of time and space, while the active, representational and reproductive faculty of the understanding provides the a priori concepts (or categories), both of which will be brought to bear on the determination of empirical objects as the conditions of all possible experience, coincident with knowledge and guided by the speculative interest of reason. The form of time delineated by Kant is empty — but productive of a single dimension of successive time whose “beginning and end simply cannot be connected”, and the form of space, likewise empty, can produce only the “infinite given magnitude” of a Euclidean and co-extensive dimensionality.83 Both forms are simultaneously subjective and objectively-valid insofar as they are generative of reality for us.84 Time, classed as ‘inner sense’, is the form of internal affection. It envelops space, or ‘outer sense’, the form of external relation and the possibility of being affected by exterior objects, which can only occur with the presupposition of time, although the two are inseparable and arise together in the human mind.85 Time can never appear to us as it is in itself and is always necessarily accompanied by space in our representations of it. Thus, we

represent the temporal sequence through a line progressing to infinity, in which the manifold constitutes a series that is of only one dimension, and infer from the properties of this line to all the properties of time, with the sole difference that the parts of the former are simultaneous, but those of the latter always exist successively.86

This succession is simply a mode of the form of time (along with persistence and co-existence, the three categories of relation whose principles are procured in the Analogies of Experience), which is not in itself successive. Nor are the modes of time properties of objects in themselves, leaving movement — dependent specifically on modal persistence — strictly subordinate to the pure form of time. Kant is adamant about this, demonstrating that if the form of time itself were successive it would be subject to a problem of infinite regress.

[C]hange does not affect time itself, but only the appearances in time (just as simultaneity is not a modus for time itself, in which no parts are simultaneous but rather all succeed one another). If one were to ascribe such a succession to time itself, one would have to think yet another time in which this succession would be possible.87

Radically indeterminate, time in itself cannot be equivalent to its parts. It corresponds to the figure of the straight labyrinth insofar as it is “in(di)visible” and — because it accompanies all of our representations — “incessant”.88 To confuse the form of time with time-as-succession is a grave metaphysical error. In the universe of the straight labyrinth, as Deleuze writes, “[i]t is not succession that defines time, but time that defines the parts of movement as successive inasmuch as they are determined within it”.89 Space in itself, in a similar fashion, cannot be construed following a pre-supposed grammar, the eclipse of Euclidean axioms in the history of mathematics having no bearing on it as a pure form.90 The fact that experience appears to unfold along a linear timeline and in three pitiful dimensions is simply a constitutive quirk of human mental structure. Insofar as we can grasp their being in themselves as pure forms, space “signifies nothing at all” and “time”, for us, “is nothing”.91

A priori synthesis occurs between the a priori categories on the one hand, and the a priori forms of spatio-temporal determination, on the other, before they are applied to experience, furnishing its “rules of construction”.92 Since both components of the synthesis are a priori, they hold as universal and necessary laws for everything that can be determined in experience. To return to Deleuze’s example of the line, the Euclidean proposition, ‘the straight line is the line which is ex aequo in all its points’ is an analytic judgement; the statement ‘this straight line is red’ is an empirical judgement (straight lines are not universally and necessarily red). The statement, ‘the straight line is the shortest path between two points’, however, is different, because the concept ‘shortest path’ is not analytically contained within the concept ‘straight line’, nor is it simply contingent on an empirical encounter: it is a priori — it holds for all straight lines — and yet, it is also synthetic — something new is added in the synthesis. ‘Shortest path’ is not a predicate of the subject ‘straight line’ but a rule for the construction of a figure that requires assembly in space and time: to produce a straight line, one must find the shortest path between two points. Put differently, a spatio-temporal determination must be discovered that accords with the concept ‘shortest path’. Kant has two texts, one written before and one written after the Critique of Pure Reason, in which he deals with the problem of ‘incongruent counterparts’ or enantiomorphic bodies, using the necessity of the spatio-temporal assembly of a concept in experience to defend the heterogeneity of space-time and concepts so integral to the difference between sensibility and understanding in the First Critique.93 A left and a right hand, for example, both of which are determined by the selfsame concept, with all its internal relations intact, are conceptually identical yet different due to their positions in space. A left hand can never be superimposed upon a right hand without exiting the confines of Euclidean dimensionality. In a similar fashion, a hand that is perceived now and a hand that is perceived in the future may belong to the same concept, but they can never be made to coincide in time. Thus, space and time are not reducible to conceptual determinations. We will return to Kant’s ‘hands’, but for now let this thought experiment of his show that, given the laws of the three-dimensional space that experience must unfold in, there is no possible way of constructing the ‘shortest path’ other than along a straight line, and to draw a line rather than a point, one requires time. Furthermore, no empirical experience will yield a straight line that is anything other than the shortest path between two points. The a priori forms of space and time thus harbour an irrefutable constitutive power that will underlie the empirical determination of all possible experience. Because both successive time and three-dimensional space belong a priori to the faculty of sensibility, and therefore have their provenance in the human mind, they are impossible to exit from for us, and must accompany every single denomination of what will be considered legitimate knowledge, which takes its declination from the intersection of empirical experience and the restrictions imposed upon the latter by the transcendental exigency that produces it.94 Dreams and hallucinations, occurring solely within the mind, constitute nothing more than a “blind play of representations” — intuitions deprived of determinate objects — and are therefore illegitimate as a basis for knowledge.95 This holds equally for our non-empirically validated Ideas of God, World and Soul (objects of a concept for which there is no corresponding intuition), any concept of an object deprived of sense data, and any contradictory and therefore impossible concept — and everyone finds themselves in the same, spatio-temporal manifold, under the same categorical laws which together act as a guarantor for the universalisability of human knowledge.96 Consequently, we discover that “we ourselves bring into appearances that order and regularity in them that we call nature”, and moreover “we would not be able to find it there if we, or the nature of our mind, had not originally put it there”.97 Although it underwrites the operation of the transcendental apparatus at the most fundamental level, time, in the First Critique, is simply an inert and ultimately unknowable form which beats out a series of inexorable, successive moments in experience. It is prior to matter, movement and extension, and thus completely re-arranges or unhinges the determination of time by motion so integral to the revolving door of the pre-critical cosmos. All change, alteration and variation take place in time, but the form of time itself is invariable and inviolable. Time Compression (Circuitry)

Overcoming the irreconcilability of rationalist and empiricist methodologies via the innovation of a priori synthesis nevertheless generates a new problem for Kant, for he has simply moved its incompatibility into the subject, under the guise of the two faculties of sensibility and understanding, which are fundamentally different in kind, one being passive, receptive and immediate, the other spontaneous, active and mediate. Kant’s infamous Copernican revolution, although beginning in radical unfaithfulness — replacing god with time — resolves the duplicitous tension it cannot help but introduce between the two sides of its trademark a priori syntheses in a fundamental identity and a vexed harmony negotiated through the enigmatic synthesis of the imagination in the Transcendental Deduction, which reconstructs the syntheses along the contours of the epistemological subject / object divide, remodelled as the transcendental unity of apperception and the transcendental object = [x].

In order to connect the abstract bundle of categories in the form of the transcendental object = [x] to experience, Kant requires a link which he locates in the imagination, generative of a transcendental synthesis of the appearance of objects across space and time by stabilising their manifolds into a consistent unity for the application of concepts. The imagination performs this role via three syntheses which occur together (but are grounded in the third) in order to produce representation: the synthesis of apprehension which formalises sensible intuitions (diversity in time and space, and the diversity of time and space) into representable shape within a space-time grid, generating a single and uniform spatio-temporal manifold subject to extensive measurement; the reproduction of spatial coordinates that are not subject to instantaneous apprehension (the momentarily non-appearing parts of a volume, for example) as well as past and projected (future) coordinates in the present; and the synthesis of recognition, which underwrites the possibility of representably-stable conceptual traction via the relation of the prior syntheses of apprehension and reproduction to the form of the object in the understanding, the ‘object = [x]’, and this relative to the synthesising subject’s own transcendental identity, the ‘unity of apperception’.98 The first two syntheses structure a determination of space and time and the third relates it to consciousness, together supplying an a priori basis for the spatio-temporal unity and continuity of experience — intuited by us as one-dimensional time and three-dimensional space, only objectively actualisable in extensity, due to the envelopment of space within the inner sense of time — comprised of conscious perceptions anchored to a unified identity.99 The kind of compression enacted by the synthesis of imagination is not simply a linear one, but the flattening of time and space into a homogenous metric upon which the understanding enacts its determinations — which only then provides a basis for linear compression or acceleration in extensity, such as that detailed by Hölderlin in his rhythmic diagrams of Oedipus and Antigone. Curiously, Kant employs the example of cinnabar to demonstrate the successive, temporal aspect of the reproductive synthesis (which supplies the recognising synthesis with its input) — an intriguing reference given its long history of alchemical and esoteric use. “If cinnabar were now red, now black, now light, now heavy”, he writes

if a human being were now changed into this animal shape, now into that one, if on the longest day the land were covered now with fruits, now with ice and snow, then my empirical imagination would never even get the opportunity to think of heavy cinnabar on the occasion of the representation of the colour red. [W]ithout the governance of a certain rule to which the appearances are already subjected in themselves … no empirical synthesis of reproduction could take place. There must therefore be something that itself makes possible this reproduction of the appearances by being the a priori ground of a necessary synthetic unity of them.100

The conceptual identity of a piece of cinnabar, along with its empirical variations, endures in time because we are able to synthesise past experiences of cinnabar with present ones via their reproduction as images in memory. We produce a recognition of categorical consistency through the relation of ‘cinnabar moments’ in the spatio-temporal manifold by connecting them to the object we are determining as a piece of cinnabar by means of its steady appearance across different times to the transcendental cogito, whose persistence as an identity is presupposed by the act of recognition. Meanwhile, the endurance of cinnabar perceptions must, according to Kant, be sufficiently objectively consistent for this to be possible in the first place, for if the objective world was in itself so chaotic that such consistency could not take place, neither would our syntheses of it. The Kantian ‘I think’ is thereby an identity which recognises itself as such against the differences it measures empirically and supposes objectively. A move that is only made possible through the combination of the syntheses of the unity of apperception and the spatio-temporal ordering effectuated under the faculty of the imagination. Together, the three syntheses of the imagination place the receptive faculty of sensibility that is productive of apprehension and reproduction in communication with the active faculty of understanding, which plugs them into the object = [x] and the transcendental unity of apperception, ostensibly resolving the problem of these faculties’ conflicting natures in the direction of categorical tractability, and subsuming spatio-temporal difference under a conceptual unity.101

Due to this implicit vectorisation — from sensibility to understanding — the transcendental synthesis of the imagination can be grasped as an “aesthetic” function made to conform to a conceptual, recognising one, which gives it its axioms — something we shall find reason to return to as the mystery of Lönnrot, Carter and Challenger continues to unfold.102 Its operation applies a unit of measure — Kant’s ‘magnitudes’ — to the sensible manifold in order to relate it to conceptual elements in the synthesis of recognition. Kant will have cause, in the Third Critique, to show the fragility of the transcendental synthesis of the imagination, one that is subject to the breaking of its measure by insurgent forces erupting from below. Subterranean revolt on behalf of the cold earth’s volcanic core. With a unified conceptual identity providing the transcendental ground for the objective validity of the categories, and a consistent, extended and sequenced spatio-temporal manifold furnishing the foundation for all appearances in intuition established via the deduction, Kant will attempt to knit the two together in the application of the principles of judgement that constitute the schematism, consolidating the objectivity of the phenomenal-real. The schematism is the temporalisation of the categories, and thus works in reverse order to the operation of the transcendental synthesis of the imagination — beginning with a concept and determining the spatio-temporal manifold in accordance with it. The three syntheses of the imagination, taken together as a single mechanism, provide the rules for recognition; schematisation, on the other hand, gives the rules of construction for a concept in space and time. The understanding, under the guise of judgement, deploys or expresses the spontaneous syntheses of the unity of apperception and the imagination in time, completing the a priori synthetic weave between expansive sense experience and categorical contraction.103 Each of the four divisions of the categories warrants a different form of expression: the three categories of quantity (unity, plurality, totality) express extensive magnitudes; the three categories of quality (reality, negation, limitation) express intensive magnitudes; the three categories of relation (inherence and subsistence, causality and dependence, community and reciprocity) establish the objectivity of time and space, and the three categories of modality (possibility/impossibility, existence/non-existence, necessity/contingency) generate the postulates of empirical thought in general. It is this penultimate group (developed in the reciprocally arising conditions of the Analogies of Experience) which confine all human experience to a universalisable temporality, and unfold change in time, consonant with the thermodynamic arrow.104 The unfolding of all four categorial groups through a priori synthetic judgements constitute acts of representation, which yield the actuality of the world for us, founding all knowledge upon representation as an activity of the human mind bound to temporal succession. The schematism is therefore,

nothing but a priori time-determinations in accordance with rules, and these concern, according to the order of the categories, the time-series, the content of time, the order of time, and finally thesum total of time in regard to all possible objects. From this it is clear that the schematism of the understanding through the transcendental synthesis of imagination comes down to nothing other than the unity of the manifold of intuition in inner sense, and thus indirectly to the unity of apperception, as the function that corresponds to inner sense (to a receptivity).105

As a result, there are certain pieces of information we will always know in advance regarding the possibility of anything whatsoever in experience, despite the a posteriori nature of certain aspects of the latter. Namely, that “all appearances are, as regards their intuition, extensive magnitudes”, and “in all appearances the sensation, and the real, which corresponds to it in the object (realitas phaenomenon), has an intensive magnitude, i.e. a degree”.106 Kant defines an extensive magnitude as ‘that in which the representation of the parts makes possible the representation of the whole (and therefore necessarily precedes the latter)’.107 A unity in extensive magnitude is composed of successive or co-extensive parts that can be added together due to the fact that they share a homogenous unit of measure.108 The nature of their difference is therefore external — a difference between parts. For the categories of quantity, the fact that appearances are systematically subordinated to extension is straightforward, for this is how we apprehend space and time — unified “multitudes of antecedently given parts”.109 For the categories of quality, however, the surety of advance knowledge is less naturally evident because it bears on sensation and thus involves an entirely subjective, empirical input. So much so that Kant will even write, years later, in the Opus Postumum that

It is strange — it even appears to be impossible, to wish to present a priori that which depends on perceptions (empirical representations with consciousness of them): e.g. light, sound, heat, etc., which all together, amount to the subjective element in perception (empirical representation with consciousness) and hence, carries with it no knowledge of an object. Yet this act of the faculty of representation is necessary.110

Intensive magnitude is a property of the real of sensation and is therefore strictly empirical, yet we are said to have a priori knowledge of it. This is guaranteed by the conspiracy of the transcendental unity of apperception and the object = [x] that gives sensation its determinate form, and it is therefore this form alone — not the determination but the form of determination — which can be anticipated. Thus we can know in advance that every conscious representation we can ever have will involve a degree of intensity, without knowing anything about the specificities of the intensities which will affect us. To this end, Kant defines intensive magnitude as that “which can only be apprehended as a unity, and in which multiplicity can only be represented through approximation to negation = 0”.111 Unlike extensive magnitudes, which imply a continuous aggregation of homogenous parts, intensities differ internally on an infinite continuum (“of which no part … is the smallest”) between 0 and n, and therefore must be apprehended instantaneously.112 However, because of the nature of our perception, intensive magnitudes cannot be perceived separately from space and time and thus come to “fill” extended magnitudes to various degrees.113 Consequently, the intensive property of internal difference is controlled by extension, locked — forever — into the extensive matrix of apprehended space-time. Most significantly of all, Kant tethers zero intensity to pure consciousness, so that the subtraction of intensive matter from experience only reaffirms, in the absence of contaminants, the immaculacy of thought.

[F]rom the empirical consciousness to the pure consciousness a gradual alteration is possible, where the real in the former entirely disappears, and a merely formal (a priori) consciousness of the manifold in space and time remains; thus there is also a possible synthesis of the generation of the magnitude of a sensation from its beginning, the pure intuition = 0, to any arbitrary magnitude.114

Sensation degree zero indexes the annihilation of reality, not the subject. This division, although Kant will go on to qualify it (writing that such an occurrence is not “to be encountered”, an empty concept without an object comprising one of the four classes of illegitimate “nothing”) makes the separation between sensible matter and thought inherent to the transcendental apparatus luminously clear.115Kant thinks intensity, but only in a way that renders it secondary both to the form of its appearance in extensity and to the pervasive authority of transcendental conceptualisation under the law of the understanding — “[subjectifying] abstraction” and “[sublimating] death into a power of the subject”, all for the sake of maintaining a spurious notion of transcendental accord.116

For the Timaean cosmos, harmony between subject and object takes the form of an external, teleologically-assured likeness between copy and model; for Leibniz, it finds its expression in the notion of final accord, and for Hume it must, no matter how reluctantly, be presupposed.117 The ideal of externally sanctioned accord between subject and object is overturned in the Critique of Pure Reason by the necessary submission of objects to the subject, which refocuses the division between subject and object to that between active and passive faculties interior to the process of determination. We have seen above how the transcendental synthesis of the imagination operates to bridge the divide. This causes Kant to rely on the understanding to rein in the productive function of imagination, subordinating its syntheses to unified identity in the transcendental subject and unified objectivity in the transcendental object, their productions nourished by passive sensibility. Reason, the third of the three active faculties (alongside the understanding and the imagination), by analogy with the function of understanding, attempts to determine its own purely conceptual objects without the necessary components of time and space furnished by sensibility, and in so doing, exercises its powers ‘problematically’ in the production of noumena — illusory totalities which nonetheless have a positive role to play in systematising the knowledge produced under the aegis of understanding in its stewardship of the syntheses.118 It can be seen, therefore, that it is the faculty of understanding that is charged with the task of limiting the functions of the other faculties in the production of experience, confining them to specific operations and drawing the boundary dividing legitimate from illegitimate knowledge. Although the three Critiques work together to define the ends of speculative reason, “[p]ure reason”, in the First Critique, “leaves everything to the understanding”, casting it in the role of legislator so that, in the great critical tribunal, it might judge according to the interests of reason, even when this entails turning against reason’s own products.119 Knowledge is thus lent a maximum of systematic unity via the relation between faculties delineated in the First Critique, which is nominally harmonious without invoking the divinity of pre-established harmony that animated pre-critical philosophy. Instead, it produces an accord of “common sense”, the “subjective condition of all ‘communicability’” — a return to the comfort of rhyme, now resonating between the faculties, mirroring thought in its objects.120 Kantian accord may be understood as an innovation of pre-established harmony, but it retains lineaments of the Platonic Idea of the good in that it still sees thought imbued with health and an honourable will, naturally inclining towards truth via the “best possible distribution” of its capacities.121 And why would it be otherwise? Surely reason, the “highest court of appeals for all rights and claims of our speculation, cannot possibly contain original deceptions and semblances”!122 By means of the accord of common sense, we recognise ourselves in the objects of the world. What a surprise, after all this, to rediscover our own silhouettes still flickering on the cavern wall. Common sense is “the norm of identity from the point of view of the pure Self and the form of the unspecified object which corresponds to it”, it is always related to recognition, and “relies upon a ground in the unity of a thinking subject of which all the other faculties must be modalities”.123 To thinking, common sense contributes only “the form of the same”.124 The democratic distribution of capacity and similitude is philosophy’s principal doxa, subtending what Deleuze will famously denounce — in Difference and Repetition — as “the Image of Thought”.125 If is not simply an illegitimate presupposition, saturated in humanist bias, whence does this principle arise? There is a deeper problem with the positing of fundamental accord between the faculties in the Critique of Pure Reason, and Deleuze will turn the legal distinction between rights and facts used in the Transcendental Deduction back on Kant, asking by what right the critical philosophy takes harmony as its ground for the relation of the faculties.126 Kant, in the end, provided a remedy for this oversight, but it would not be enough to placate the tremors the critical system had induced.

Despite his predilection for tribunals, Kant’s recalibration of thought replaces the transcendence of god (and its models) as the ultimate arbiter of truth with the process of immanent critique, and thus transposes error into illusion. The strangeness of this new form of falsity springs from the fact that it is internal to the power of thought itself, contrary to the externality and materiality of error that informs Timeaus’ universe. Reason’s propensity to produce illusion as a consequence of its productive power brings Plato’s planomenon into thought itself, menacing it from inside “as if from an internal arctic zone where the needle of every compass goes mad”, a further disturbance of the cardinality which operates the turning of the great revolving door.127 This threat, nevertheless, is immediately quarantined. With the understanding commandeering synthesis, it is no longer a question of reversing of “the corruption of the circuits in our heads”, rather it is this very circuitry that constitutes the correction of illusion by forcing everything through the transcendental unity of apperception and its object = [x].128 The conservatism of the revolving door and the eruptive potential of the straight labyrinth leak into one another repeatedly throughout the First Critique. The labyrinth’s corrosive implications recognised then covered up, again and again, as if Kant realises the enormity of the abyss he has levered apart but cannot countenance its vertiginous depth, a “depth [which] is like the famous geological line from NE to SW, the line which comes diagonally from the heart of things and distributes volcanoes”.129 But Kant is no Empedocles. He does not wish to explode the sun. Asymmetry petrifies him — and for good reason.

If the Critique of Pure Reason “seemed equipped to overturn the Image of thought” in its substitution of illusion for error, the fractured I for a unified and substantialised cogito, and the invocation of the speculative deaths of God and the self, Kant

in spite of everything, and at the risk of compromising the conceptual apparatus of the three Critiques … did not want to renounce the implicit presuppositions. Thought had to continue to enjoy an upright nature, and philosophy could go no further than — nor in directions other than those taken by — common sense.130

Where Kant hesitates at the caldera’s edge, Hölderlin explores it with tortured determination, extracting from Oedipus what is truly radical in both “[t]he Greek image of thought” that “already invoked the madness of the double turning-away”, and the Kantian one, which launches “thought into infinite wandering rather than into error”.131 Vision, the Timaean antidote to corruption, is still insisted upon as the implicit other of the blindness Kant so frequently invokes, but it must be remembered that Tiresias’s prophetic knowledge is coincident with his loss of sight, and at the moment of the comprehension of his fate, Oedipus blinds himself.132

Asymmetry (Alienation)

The true innovation of the critical project, then — and that which constitutes its unprecedented modernity — is not the tiresome delineation of conditions for anthropomorphic experience productive of and produced by an intransigent conceptual faculty, but its profound reconfiguration of time. In Kant, pre-modern, cyclical, scroll-like temporality “unrolls itself like a serpent”, no longer subordinate to gods or nature — to logic, to reason, psychology, matter or sense — no longer subordinate to anything, save the mystery of its own inner workings, an enigmatic process of auto-affection.133 An impersonal reading of the First Critique reveals this immediately: the subject may have a productive role in the constitution of phenomena, but it is always in the thrall of something it has no empirical access to, which, in turn, is producing its production of experience.134 Both of these productive syntheses are temporal and, necessarily for Kant — who has reached for the one thing common to the two sides of the rift he has opened up inside the transcendental production of experience — only legitimately reconcilable by yet another temporal function: the application of the categories to experience in time via the faculty of judgement.135 Rather than a fortification of subjective prowess in the realm of experience, the Critique of Pure Reason is the story of time’s relation to itself, through itself — and this relation takes the form of a limp.