|

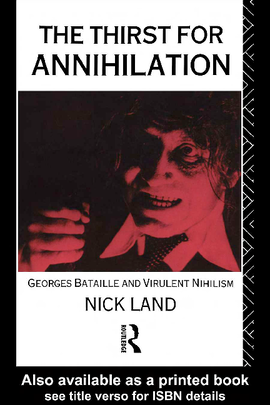

by Nick Land It is tempting to understand the difference between ‘general’ and ‘restricted’ economy as commensurate with that between ‘closed’ and ‘open’ systems. In both cases the former terms seem to refer to the total field of energy exchange, and the latter to the differentiated regions within such a field. A translation of this kind is not wholly inappropriate, but it simplifies the situation excessively. That which circulates in an economy of the kind Bataille describes is less a ‘content’ with a general and a local intelligibility than the capacity for relative isolation or restriction as such. There is a sense (that of scientific objectivism) in which utility presupposes negative entropy, but abstract order of this kind is quite different from the ‘canalization’ [VII 467] which is utility’s basic characteristic. The quasi-autonomous territories which inhibit the concrete universalization of the second thermodynamic law are not conditions of ‘composition’ as Bataille uses this term, they are composition as such. In other words, composition is simultaneous with the real differentiation ‘of’ space. It is thus that Bataille extracts ‘production’ from the idealist schemas which continue to operate within Marx’s analysis, those lending the critique of political economy a marked humanist tendency. Work is not an origin, sublating divine creation into historical concretion, but an impersonal potential to exploit (release) energy. The humanized exploitation of class societies is not without a prototype, since surplus production is only possible because of the solar inheritance it pillages. Bataille’s solar economics is inscribed within the lacuna in Marxism opened by the absence of a theory of excess, and describes the truly primitive (impersonal) accumulation of resources. Such cosmichistorical economy is axiomatized by the formula that ‘the energy produced is superior to the energy necessary to its production’ [VII 466], and maps out the main-sequence of terrestrial development, from which the convulsions of civilization are an aberration. Strictly speaking, the libidinal main-sequence, impersonal accumulation, or primary (solar) inhibition, emerges simultaneously with life, and persists in a more or less naked state up until the beginning of sedentary agriculture, sometime after the last ice-age. Life is simply the name we give to the surface-effects of the mainsequence. Compared to the violently erratic libidinal processes that follow it, the main-sequence seems remarkably stable. Nevertheless, libido departs from its pre-history only because it has already become unstable within it, and even though the preponderant part of the main-sequence occurs within a geological time-span, the evidence of a basic tendency to the geometric acceleration of the process is unmistakable. The main-sequence is a burning cycle, which can be understood as a physico-chemical volatilization of the planetary crust, a complexification of the energy-cycle, or, more generally, as a dilation of the solar-economic circuits that compose organic matter, knitting it into a fabric that includes an ever-increasing proportion of the (‘inorganic’) energetic and geo-chemical planetary infrastructure. Of course, the distinction between the organic and the inorganic is without final usefulness, because organic matter is only a name for that fragment of inorganic material that has been woven into meta-stable regional compositions. If a negative prefix is to be used, it would be more accurate to place it on the side of life, since the difference is unilateral, with inorganic matter proving itself to be non-exclusive, or indifferent to its organization, whereas life necessarily operates on the basis of selection and filtering functions. When colloidal matter enters the main-sequence it begins to differentiate two tendencies, which Freud characterized at a higher level with a distinction between ‘φ’ and ‘ψ’, or communication and isolation (immanence/transcendence, death and confusion)8. Organic libido emerges with the gradual differentiation of what seem superficially to be two groups of drives (Freud does not describe them as such until later). A progressive tendency isolates or ‘individuates’ the organism, first by nucleation (prokaryotes to eukaryotes), and then through the isolation of a germ-line, dividing the protoplasm into ‘generative cells’ and ‘somatic cells’. This is the archaic form of Freud’s ‘Eros’; on the one hand a tension between soma and generation, and on the other a conservation of dissipative forces within an economy of the species, leading ultimately to sexuality. But this erotic or speciating tendency is perpetually endangered by a regressive tendency that leads to dissolution (Thanatos). The ‘φ’ or communication tendency accentuates the various ‘interactions’ between biological matter and its ‘outside’, and is thus equivalent to a lowering of the organic barrier threshold, essential to photo-reactivity, assimilation, cybernetic regulation, nutrition, etc. This is the complex of organic functions which Bataille associates with primary immanence. The ‘ψ’ or isolation tendency is the inhibition of exchange, a raising of the barrier threshold that generates a measure of invariant stability, the conservation of code, controlled expenditure of bio-energetic reserves, etc. The combined operation of these tendencies effects a selective distribution in the degree of fusion between the organism and its environment (a difference that is not given but produced), which precariously stabilizes a level of composition. The maximum state of φ ( φmax) is equivalent to the complete dissolution of the organism, at which point its persistence would be a matter of unrestricted chance, free-floating at the edge of zero. At any other level of φ the organism sustains a measure of integration, and what we call ‘the organism’ is only this variable cohesiveness, or intensity: the real basis of Bataille’s ‘transcendence’; the mazefringe of death. Isolation or transcendence (ψ) is an intensive quantity, since it lacks pre-given extensive co-ordinates. In other words, there is no logico-mathematical apparatus appropriate to the emergence of ψ, since ψ ‘is itself’ the basic measure of identifiability or equivalence. Communication (φ) escapes both identity and equivalence because it is indifferentiation or uninhibited flow; the intensive zero, energy-blank, silence, death. Only differentiation from φ (dφ=ψ) is able to function as a resource, storing energy, and precipitating compositions (forms, behaviours, signs). The intensive quantity ψ is therefore the basis and currency of extensive accumulation. Bataille’s economics is based on the principle that extensive exchange (ψ1 → ψ2) is primitively accumulative. The extensive exchange is comprised of two intensive transitions: an expenditure (ψ → φ) and an acquisition (φ → ψ), with the latter always exceeding the requirement of replacement, so that ψ1 < ψ2. Bataille’s emphasis on this point leaves little room for misunderstanding: ‘the energy that the plant appropriates to its mode of life is superior to the energy strictly necessary to that mode of life’ [VII 466], ‘the appropriated energy produced by its life is superior to the energy strictly necessary to its life’ [VII 466]. ‘It is of the essence of life to produce more energy than that expended in order to live. In other words, the biochemical processes are able to be envisaged as accumulations and expenditures of energy: all accumulation requires an expense (functional energy, displacement, combat, work) but the latter is always inferior to the former’ [VII 473]. More technically: ψ1 → ψ2=dφ → d+nφ. Marx entitled his basic project ‘the critique of political economy’, which is something similar to what some might now call a ‘double reading’ in that—interpreting the accounts that the bourgeoisie give of their economic regime—Marx found that the word ‘labour’ was being used in two different senses. On one hand it was being used to designate the value imparted by workers to the commodities they produce, and on the other hand, it was being used to designate a ‘cost of production’ or price of labour to an employer. With the ascent of the Ricardian school the tradition of political economy had reached broad agreement that the price of a commodity on the market depended upon the quantity of labour invested in its production, but if workers are being paid for their labour, which then adds to the value of the product, it is impossible to detect any opening for profit in the production and trading of goods. Marx’s basic insight was that being paid for one’s labour, and the value of labour, were not at all the same thing. He coined the term ‘labour-power’ [Arbeitskraft] for the object of transaction between worker and employer, and kept the word ‘labour’ [Arbeit] solely for the value produced in the commodity. Having thus distinguished the concepts of ‘labour’ and ‘labour-power’ the next step was to explore the possibility that labour-power might function as a commodity like any other, trading at a price set by the quantity of labour it had taken to produce. The difference between the capacity for work and the quantity of work necessary to reproduce that capacity would unlock the great mystery of the origin of profit. If labour were traded in an undistorted market with complete cynicism it should command a price exactly equal to the cost of its subsistence and reproduction at the minimal possible level of existence, just as any other commodity traded in such a market should tend towards a price approximating to the cost of the minimal quantity of labour time needed for its manufacture. Marx thus speculated that the average price of labour within the economy as a whole should remain broadly equivalent to the subsistence costs of human life. Thus: Value of labour—Price of labour=Profit But why is it that labour-power comes to trade itself at a price barely adequate to its subsistence? There is a twofold answer to this, the first historical and the second systematic, although such separation is possible only as a theoretical abstraction. Both of these interlocking arguments are accounts of the excess of labour, or of the saturation of the labour market: 1. In the section of Capital entitled ‘The So-called Primitive Accumulation’ Marx attempts to grasp the inheritance of capital, and is led to examine a series of processes which are associated with the events in English history which are usually designated by the word ‘enclosure’. Broadly speaking the mass urbanization of the European peasantry, which separated larger and larger slices of the population from autonomous economic activity, was achieved by a more or less violent expulsion from the land: The prelude of the revolution that laid the foundation of the capitalist mode of production, was played in the last third of the 15th, and the first decade of the 16th century. A mass of free proletarians was hurled on the labour-market by the breaking-up of the bands of feudal retainers, who, as Sir James Steuart well says, ‘everywhere uselessly filled house and castle.’ Although the royal power, itself a product of bourgeois development, in its strife after absolute sovereignty forcibly hastened on the dissolution of these bands of retainers, it was by no means the sole cause of it. In insolent conflict with king and parliament, the great feudal lords created an incomparably larger proletariat by the forcible driving of the peasantry from the land, to which the latter had the same feudal rights as the lord himself, and by the usurpation of the common lands. The rapid rise of the Flemish wool manufacturers, and the corresponding rise in the price of wool in England, gave the direct impulse to these evictions. The old nobility had been devoured by the great feudal wars. The new nobility was the child of its time, for which money was the power of all powers. Transformation of arable land into sheepwalks was, therefore, its cry [Cap 672]. Urbanization is thus in one respect a negative phenomenon; a type of internal exile. In the language of liberal ideology the peasantry is thus ‘freed’ from its ties to agrarian production. Liberté! 2. The labour market is historically saturated by the expropriation of the peasantry, but it is also able to generate such an excess from out of an intrinsic dynamic. In other words, capital creates unemployment due to a basic tendency to overproduction. The pressure of competition forces capital to constantly decrease its costs by increasing the productivity of labour-power. In order to understand this process it is necessary to understand two crucial distinctions that are fundamental to Marx’s theory. Firstly, the distinction between ‘use value’ and ‘exchange value’, which is the distinction between the utility of a product and its price. Every commodity must have both a use value and an exchange value, but there is only a very tenuous and indirect connection between these two aspects. An increase in productivity is a change in the ratio between these facets of the commodity, so that use values become cheaper, and labour power can be transformed into a progressively greater sum of utility. Marx seeks to demonstrate that this transformation is bound up with another, which has greater consequence to the functioning of the economy, and which is formulated by means of a distinction between ‘fixed capital’ and ‘variable capital’. Fixed capital is basically what the business world calls ‘plant’. It is the quantity of capital that must be spent on factors other than (direct) labour in order to employ labour productively. As these factors are consumed in the process of production their value is transferred to the product, and thus recovered upon the sale of the product, but they do not—in an undistorted market—yield any surplus or profit. Variable capital, on the other hand, is the quantity of capital spent on the labour consumed in the production process. It is capital functioning as the immediate utilization of labour power, or the extraction of surplus value. It is this part of capital, therefore, that generates profit. Marx calls the ratio of variable capital to fixed capital the organic composition of capital, and argues that the relative increase in use values, or improvements in productivity, are—given an undistorted labour market—associated with a relative increase in the proportion of fixed capital, and thus a decrease in profit. The problems that have bedevilled Marxian theory can be crudely grouped into two types. Firstly, there is the empirical evidence of increasing metropolitan profit and wage rates, often somewhat hastily interpreted as a violation of Marx’s theory. In fact, the problem is a different though associated one: the absence of a free-market in labour. Put most simply, there has never been ‘capitalism’ as an achieved system, but only the tendency for increasing commodification, including variable degrees of labour commodification. There has always been a bureaucratic-cooperative element of political intervention in the development of bourgeois economies, restraining the more nihilistic potentialies of competition. The individualization of capital blocks that Marx thought would lead to a war of mutual annihilation has been replaced by systematic statesupported cartelling, completely distorting price structures in all industrial economies. The second problem is also associated with a state-capital complex, and is that of ‘bureaucratic socialism’ or ‘red’ totalitarianism. The revolutions carried out in Marx’s name have not led to significant changes in the basic patterns of working life, except where a population was suffering from a surplus exploitation compounded out of colonialism and fascism, and this can be transformed into ‘normal’ exploitation, inefficiently supervised by an authoritarian state apparatus. Marxism—it is widely held— has failed in practice. Both of these types of problem are irrelevant to the Marxism of Bataille, because they stem, respectively, from theoretical and practical economism; from the implicit assumption that socialism should be an enhanced system of production, that capitalism is too cynical, immoral, and wasteful, that revolution is a means to replace one economic order with a more efficient one, and that a socialist regime should administer the public accumulation of productive resources. For Bataille, on the contrary, ‘capital’ is not a cohesive or formalizable system, but the tyranny of good (the more or less thorough rationalization of consumption in the interests of accumulation), revolution is not a means but an absolute end, and society collapses towards post-bourgeois community not through growth, but in sacrificial festivity. Beyond political economy there is general economy, and the basic thought at its heart is that of the absolute primacy of wastage, since ‘everything is rich which is to the measure of the universe’ [VII 23]. Bataille insists that all terrestrial economic systems are particular elements within a general energy system, founded upon the unilateral discharge of solar radiation9. The sun’s energy is squandered for nothing (=0), and the circulation of this energy within particular economies can only suspend its final resolution into useless wastage. All energy must ultimately be spent pointlessly and unreservedly, the only questions being where, when, and in whose name this useless discharge will occur. Even more crucially, this discharge or terminal consumption—which Bataille calls ‘expenditure’ (dépense)—is the problem of economics, since on the level of the general energy system ‘resources’ are always in excess, and consumption is liable to relapse into a secondary (terrestrial) productivity, which Bataille calls ‘rational consumption’. The world is thus perpetually choked or poisoned by its own riches, stimulated to develop mechanisms for the elimination of excess: ‘it is not necessity but its contrary, “luxury”, which poses the fundamental problems of living matter and mankind’ [VII 21]. In order to solve the problem of excess it is necessary that consumption overspills its rational or reproductive form to achieve a condition of pure or unredeemed loss, passing over into sacrificial ecstasy or ‘sovereignty’. Bataille interprets all natural and cultural development upon the earth to be sideeffects of the evolution of death, because it is only in death that life becomes an echo of the sun, realizing its inevitable destiny, which is pure loss. This basic conception founds a materialist theory of culture far freer of idealist residues than the representational accounts of the dominant Marxist and psychoanalytical traditions, since it does not depend upon the mediation of a metaphysically articulated subject for its integration into the economic substrate. Culture is immediately economic, not because it is traversed by ideological currents that a Cartesian pineal gland or dialectical miracle translates from intelligibility into praxis, but because it is the haunt of literary possibilities that constantly threaten to transform the energy expended in its inscription into an unredeemed negative at the level of production. Poetry, Bataille asserts, is a ‘holocaust of words’. A culture can never express or represent (serve) capital production, it can compromise itself in relation to capital only by abasing itself before the philistinism of the bougeoisie, whose ‘culture’ has no characteristics beyond those of abject restraint, and self-denigration. Capital is precisely and exhaustively the definitive anti-culture. Capitalism, then, is (the projection of) the most extreme possible refusal of expenditure. Bataille accepts Weber’s conclusions concerning the relationship between the evolution of capital accumulation and the development of Protestantism, seeing the Reformation critique of Catholicism as essentially a critique of religion insofar as it ‘functions’ as a means of economic consumption, or as a drain for the excess of social production. The Protestant repudiation of indulgences—as well as its rejection of lavish cathedral building and the entire socio-economic apparatus allied to the doctrine of salvation through ‘works’—is the cultural precondition for the economy closing upon itself and taking its modern form. Bourgeois society is thus the first civilization to totally exclude expenditure in principle, opposed to the conspicuous extravagance of aristocracy and church, and replacing both with the rational or reproductive consumption of commodities. It is this constitutive principle of bourgeois economy that leads inevitably to chronic overproduction crisis, and its symptomatic redundancies of labour and capital. It is not that capital production ‘invents’ the crisis which comes to be named ‘market saturation’, it is rather that capital production is the systematic repudiation of overproduction as a problem. To acknowledge the necessity of a stringent (although perpetually displaced) limit to the absorption of surplus production is already to exceed the terms in which the bourgeoisie or administrative class can formulate its economic dilemmas. A capital economy is thus one that is regulated as if the problem of consumption could be derived in principle from that of production, so that it would always be determinable as an insufficiency of demand (during the period roughly between 1930 and 1980 this has typically led to quasi-Keynesian solutions nucleated upon US armaments spending). Bataille, in contrast, does not see a problem for production in the perpetual reproduction of excess, but rather, in a manner marking the most radical discontinuity in respect to classical political economy, sees production itself as intrinsically problematic precisely insofar as it succeeds. by the book: The Thirst for Annihilation/Chapter 2: The curse of the sun by Nick Land

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Steven Craig Hickman - The Intelligence of Capital: The Collapse of Politics in Contemporary Society

Steven Craig Hickman - Hyperstition: Technorevisionism – Influencing, Modifying and Updating Reality

Archives

April 2020

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed