|

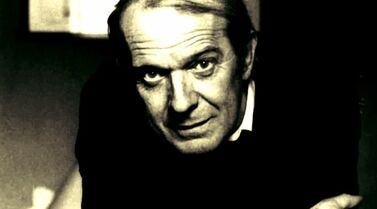

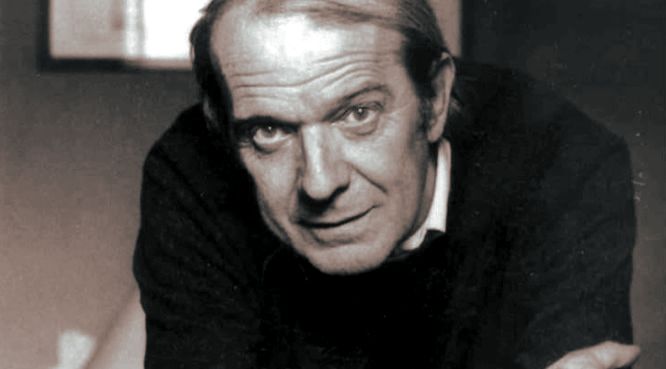

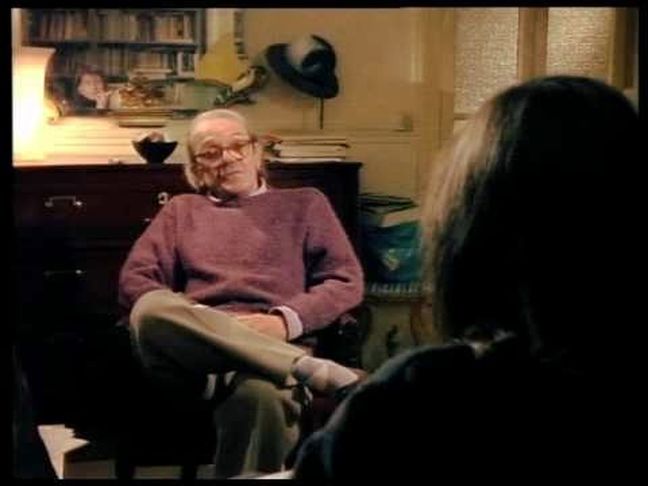

Marcus Moure’s 1995 interview with J.G. Ballard about his novel Rushing To Paradise  Ballard is one of the best writers of speculative fiction alive today. Whether exploring the innate sexuality of automobile accidents, the power of dreams as reality, or navigating through the rubble of modern civilization, his often savage, apocalyptic work has influenced artists and filmmakers alike. Ballard himself counts among his influences the surrealist painters Dali, Magritte, and Ernst, as well as William Burroughs, whom he considers to be one of the most important authors of the twentieth century. Ballard first entered the literary world as a science fiction writer, a genre he soon exhausted and has not explored in years. His transition to the mainstream was not entirely smooth, however. His 1970 anthology, The Atrocity Exhibition, was deleted from the Farrar, Straus and Giroux catalogue soon after its U.S. publication because of short stories like “Why I Want to Fuck Ronald Reagan” and “Plan for the Assassination of Jacqueline Kennedy.” After reading his classic 1972 novel, Crash, an editor wryly commented, “The author is beyond psychiatric help.” I found Mr. Ballard to be quite sane – piercingly so, in fact – as he talked to me recently from his home in Shepperton, a suburb of London. Ballard is the author of 16 novels, including Hello America, The Crystal World, Empire of the Sun, The Terminal Beach, The Unlimited Dream Company and The Disaster Area. His newest novel, Rushing to Paradise, was just published by Picador U.S.A. Ballard as seen by BallardMM: How do you see yourself as a writer and what do you think is your niche in the literary world? JGB: I can’t speak for the United States, but I suppose some still refer to me as a science fiction writer. But since Empire of the Sun came out ten years ago, I think people have welcomed me to the mainstream. Although I’m not so sure I want to be embraced by the mainstream. I think I’m still what I always was, a kind of fringe writer. I think I’m an imaginative writer who began his career by writing science fiction, but I haven’t written any, really, for a very long time. I don’t even consider Crash to be a science fiction novel. I don’t know whether you’ve read it or not. MM: Definitely. It seems to me that fantastically imaginative fiction tends to be lumped in with the whole science fiction genre. JGB: Exactly. If you look at twentieth century novels, you can see that there’s a sort of mainstream, or what I would call realistic or naturalistic fiction. And then there are the imaginative writers who often tend to be mavericks. You know Genet, Celine, Burroughs, and so on. And I like to think of myself as a maverick. I’m certainly not a literary man, and this is an important point. I’ve met a great number of writers, novelists rather, English ones in particular, whose stock of references – their sort of instant associations that come to mind when they create and all that – all tend to come from the world of literature. Mine do not. I’m interested in science and medicine, the media landscape, and so on. My reflexes are not the reflexes of a literary man. I’m more of a magpie pecking at any bright pieces of foil. I’m interested in the world, not the world of literature. Science FictionMM: So you wouldn’t file your work of the past 15 or 20 years under science fiction? JGB: No, not anymore. Some of my work was, there’s certainly no question about that. And I’m very proud that I was a science fiction writer. As I’ve often said, it’s the most authentic literature of the twentieth century. Sadly enough, most science fiction is being written by the wrong people nowadays. The constraints of a certain kind of commercial fiction have tended to formularize the field over the last 50 years. MM: Speaking from my own experience, I think many people, especially as young readers, are drawn to the newness, inventiveness, even classic adventure elements of science fction, but eventually outgrow it. As you said, you find the repetition and formula simply bore you. Especially when you realise there’s so much more out there. Why limit yourself? Why be just a science fiction writer or reader? JGB: I agree with you. That’s true. And that’s why I myself stopped writing. People within the science fiction world never regarded me as one of them in the first place. They saw me as the enemy. I was the one who wanted to subvert everything they believed. I wanted to kill outer space stone dead. I wanted to kill the far future and focus on inner space and the next five minutes. And sci-fiers to this day don’t regard me as one of them. I’m some sort of virus who got aboard and penetrated the virtue of science fiction and began to pervert its DNA. Rushing to ParadiseMM: Your new novel deals with obsessive themes like fanaticism, radicalism and militant feminism, all within the frame of the extremist wing of the environmental movement. It’s not only eerily timely, it also strikes a raw nerve, especially in view of the healthy wave of anti-political correctness sweeping ouer the United States at the moment. JGB: Well, that’s a good thing, isn’t it? The great talent of the United States is to take things too far, so that you have these huge pendulum swings of sorts. Always correct and then reverse. And then correct and reverse again. Here in England, I would say the extremist fringe of the feminist movement is largely positive. I’ve got two daughters as well as a son, and they’ve benefited enormously from the feminist movement of the past 20 years. England is a very class-bound society, and women, until recently, were practically an inferior class. Most professions were closed to women 30 years ago, except teaching and publishing. Nowadays they’re all mostly open. So we do have a few extremists, but nothing compared to the U.S., where you really do have some very strange people. Sex, Violence, Censorship, RealityMM: You said in a recent interview that “Everything should be done to encourage more sex and violence on television”. JGB: Yes, I did say that. And I think it’s true. I mean, I live in the most censored nation in the Western world. There’s no question about that. Many people have said so. Film, TV videos, and art are more heavily censored here than anywhere in Western Europe or the U.S. Censorship in England has a clear political role. It represents the fear of the established order that given any sort of imaginative freedom, or too much of it, the power structure will collapse. If people see sex and violence treated frankly, they may turn the same frank eye upon their own political situation. And start climbing up the base of the pyramid towards the apex. The people in real control sanitise the view of the world for us. Absolutely. Best WorkMM: In his book, The 99 Best Novels Since 1939, Anthony Burgess considers your novel The Unlimited Dream Company to be your most important work to date. Which do you consider your best? JGB: My most original and probably best novel is Crash. This is probably where I pushed my imagination as far as it has gone. I’ve also got a soft spot for other books of mine, most notably The Atrocity Exhibition. The Atrocity Exhibition is practically incomprehensible to most readers, whereas Crash is directly intelligible. There’s no doubt at all about what the author’s getting on about. The Unavoidable QuestionMM: Can we talk about Empire of the Sun? That is, if it isn’t already an exhausted topic. What is your opinion of Steven Spielberg’s film version of your novel? JGB: I was very impressed by it. I thought it was a fine film. In fact, trying to remain as neutral as possible, I think it’s a much better film than Schindler’s List because it’s more imagined than Schindler’s List. I think the film is a remarkable effort in many ways. He extracted a wonderful performance from the boy. He was very faithful to the spirit of the book. There are always problems when Hollywood tackles a war film because the conventions of the entertainment cinema can’t really cope with the horrors of war. Still, I think it was a remarkable film, and more and more people are beginning to realize it. Current ReadingsMM: Have you read anything recently thut impressed you favourably? JGB: Well, I don’t read much fiction nowadays, to be honest. Writing the stuff all day means when I read I tend to read nonfiction. It feeds my imagination. I read a great deal, but I can’t really pick a landmark book offhand. Let’s see, well, I just finished The Moral Animal by Richard Wright, a study of neo-Darwinism. That was quite impressive. Actually the best novel I’ve read in a while is by that Danish writer Peter Hoeg, Smilla’s Sense of Snow. I thought it was a wonderful book. Far more than a mere thriller. In fact, it’s a pity that it had any thriller element to it at all. It was much more than that. It was quite remarkable on all sorts of levels. I hope it did well in the states. My girlfriend is reading his new one (Borderliners) now. Current projectsMM: What are you working on now? JGB: I’m halfway through another novel untitled as of yet – another sort of cautionary tale. I’d rather not discuss it in detail thaugh. MM: Any plans to come over to the States and promote Rushing to Paradise? JGB: Oh, probably not, I’m too engrossed in the new book. published on: www.spikemagazine.com

1 Comment

by Jasna Koteska

Most persistent readings of the works of Kafka identify Kafka as the author of intimism (Freud's nuclear family) nihilism (everything eventually comes down to the impossible out of the undefined and unfair Law) and pessimism. The study Kafka, humorist suggested that Kafka should be read as a humorist, at least for two reasons: 1) The Kafka distanced himself from the bitter mode that dominated interpretations of his work as pessimistic. Тhe most - entertainin parts of the biography for Kafka of Max Brod are dedicated to describing the humorous, clownish way in which Kafka had read parts of his novel Process to an audience of literary readings in the apartment of Brod in Prague, and the audience responded with "unstoppable laughter." 2) Reading Kafka as a comedian but not as a pessimist, paradoxically, has a long and more credible tradition.

Since in 1934, on the tenth anniversary of the death of Kafka, Walter Benjamin in his study Kafka offers his work to be read in a humorous way. Deleuze and Guattari, following the advice of Benjamin in their study in 1975 'Kafka' talks about "a very joyous laughter" in Kafka, but note that this tip to read Kafka remains almost unnoticed by his critics. Finally, David Foster Wallace, in his text Laughing with Kafka in 1998 wrote about the complexities of humour in Kafka, claiming his humour has a "heroic normal" quality. The study Kafka, humorist of Koteska, testing the guidelines which provided by Benjamin, Deleuze and Guattari and Wallace and trying to interpret the humor in Kafka through some of his most frequent themes: animalism, miniaturization, asceticism; but and: children, food, knife, machines; finally the portrait of Kafka for some of the most famous figures of his time (among other things, his comments of Charlie Chaplin and Benito Mussolini, who surprise the reader with unusual similarity in their descriptions).

1. Kafka in court: "Kilogramme Kafka"

Future fulfils the dreams of the past. We see the example of Kafka - all life built courtroom, and the posthumously entered it. A few months ago, in October 2012, a court in Tel Aviv ruled that the literary legacy of Franz Kafka becomes the property of the National Library in Jerusalem. It was the final, cynical ending, of a long and painful journey of the grandiose author of the 20th century, who, all his life devoted to the study of airless space in the courtroom. How did Kafka end up exactly where хе placed most of his opus - in court?

As is known, Kafka published very little in his life. Since before death, he destroyed most of his works, and other manuscripts delivered to the friend Max Brod with a clear instruction: to destroy them after his death. Instead of fulfilling the covenant, Max Brod preserved the manuscripts and between 1925 and 1927, at first he published the novel Process, Castle and America, and in 1935 collected works of Kafka. When he moved to Palestine in 1939, Brod took with him the rest of the papers and there he kept until his death in 1968. After the death of Brod, the manuscripts inherits his secretary and mistress Esther Hoffe, who in 1988 on public auction sells the handwriting Process for two million dollars. Then it is already clear that Kafka is not only a cult author of modern civilisation but also lucrative commodities market. Esther died in 2007, and tens of the thousands of pages of manuscripts of Kafka, who inherited her two daughters, Eva and Ruth, deposited in private safes in banks in Tel Aviv and Zurich and in 2007 they have offered on public auction and the price is established according to the simple equation: the texts of Kafka will have the same market value, and the cost per manuscript will be determined by the weight of the boxes. This means that the bidder that offers the most money per kilogramme manuscript, will become the new owner of Kafka! The absurd finish of the most brilliant contemporary descriptor of absurd is twofold. Five years ago on the market of goods was offered Kilogramme Kafka for the richest bidder, and at the same time in the battle for possession over Kafka soon include the state of Israel with a request Kafka to be treated as a legacy of the Jewish people. The problem of this solution worked out brilliantly Judith Butler in the text Who Owns Kafka? (2011). Butler, herself Jewish, in the text has questioned the legitimacy of the so-called law of return: to whom actually belongs the cultural heritage of the Jewish diaspora: to the state of Israel or the Diaspora? (Butler, 2011: 3-8) The fact that Kafka all his life stayed away from affiliation, made the right of belonging over posthumous Kafka even more traore.

The dispute over the ownership of Kafka was conducted in front of the family court in Tel Aviv, in front of the only two institutions (family court), whose disclosure Kafka dedicate all his work. Except in Jerusalem for housing the legacy of Kafka between 2007 and 2012, has fought another institution - the German Literature Archive in Marbach, the same archive who in 1988 bought the manuscript Process of the auction house - Sotheby for three and a half million dollars. As a Czech Jew, Kafka spoke a German and Czech language, but from his rich correspondence it is clear that in both languages did not feel comfortable, none of them was quite at home. Although Hannah Arendt praises Kafka as the purest German stylist, and though the Kafka briefly lived in Berlin, Kafka clearly told that he is not feel like part of Germanism (at least not in socially, even in a cultural sense). On the other hand, although he was Cech according to territorially birth and he spoke the Czech language, Kafka did not feel either as a member of the Czech culture (Milena Jasenska in letters to Kafka often corrected his Czech language, just as his fiancée Felice Bauer corrected his German language), and nor quite feel that he belongs to the Jewish tradition. Although in 1911, Kafka once a week, went to the Yiddish theater, he read Kabbalah and discussed in his diaries, then readed Jewish magazines and went to the lectures on Zionism, still in his family Kafka rarely heard Yiddish and the language is treated as East and alienated, while the desire to move to Palestine, unlike Max Brod, who was active Zionists, in Kafka is more fantasy from the other side of the experience than planned activity. And although for Hannah Arendt fact that the language of Kafka is completely cleansed of "stylistic junk" makes the clearest evidence of German, exactly that purity drives Max Brod, Kafka's work to declare for the most typical Jewish document.

Who, then, belongs Kafka? The entire work of Kafka is lament for not hosted in any of the three cultures (Jewish, German, Czech), and Deleuze and Guattari, rightly, of his brilliant study of Kafka, simply titled Kafka (1975) it gave the subtitle to a small literature ( Deleuze and Guattari, 1998: 5-155). Kafka is the author of fundamental alienation, and for the fundamental non-belonging, except eventually to the small (cultures, literature, identities). However, the knower of Kafka is doomed to dispute even with Deleuze and Guattari. Kafka thoroughly does not belong to any small cultures, languages, ideologies, because he just does not want to belong to any subclass of a human; he does not want to belong to any human, and even belongs to himself - his whole project is the idea of destroying biotic, human, even on the most - singular level. Although he was engaged, Kafka has never married. He never owned any personal property and he had not his own apartment. Finally, Kafka did not want to own even his own work, leaving the clear instruction to Max Brod to destroy all his manuscripts after his death.

The project of Kafka refined attempt to kill the human circulation of commodities, goods, love, hatred, objects, meaning ... In this sense, belonging to "A minor literature", which spokes Deleuze and Guattari, is the existence of the minor literatures and cultures "defeated but proud" because Kafka had not had pathetic attitude to his place in culture ( "I'm overwhelmed, I'm small, but I am proud, I exist"). No. And not just because Kafka did not play on the miserable map of pride, but because in Kafka is the final question of existence. He thoroughly explores the idea of a last who will testify that no longer existence, the last one witness that testify that existence no longer exists. To exist as the last, with the idea to leave a testimony of disruption in existence, to justify the non-existence - it is probably the essential message of the work of Kafka. If it's so, the logical question is: why, then, Kafka himself did not destroyed his own manuscripts, when he already was sure that he wanted his own works to disappear with him? Is not it safe, if he really wanted he himself to light his work, making sure that none of him will remain after his death? Whether the transfer of the obligation to Max Brod no longer speak that Kafka least calculating with the possibility Max Brod to reject the application from the dead Kafka and therefore perverse to accomplish precisely his thoroughly desire: "I choose to celebrate me, but even after my death, to glorify me, but only as a commodity - it will be my final victory "? This question placed those who operating with the pragmatic logic that fame or success are factors of one's existence. It Kafka is still too little to understand the complexity of the project called K. For Kafka final gesture of destruction must pass to other (must pass to Max Brod) because only that passage guarantees the continuation of the absurd. The gesture of Kafka for delayed destruction of the manuscripts is the only logical outcome of his work.

Kafka is humorist of the absurd and his last testament to the destruction of meaning must pass to other because if Kafka himself burned his writings, he would close the circle of nonsense, while the work is always in the game to stay possibility absurd to transfer as a minimal message, as a minimal game. In that game, Kafka pledges all his work. And in this sense, the world really touched the absurdity of Kafka, when, turning his work into a commodity altercation in the front of the family court, really confirmed his masterful diagnosis: that civilisation will become only more movingly banal, and more pathologically dangerous that this culture, people and works only increasingly be replaced by items. Kafka ensures that beyond the existence, to the world will direct his own question: Do you not see that I had left my latest toy as evidence of not belonging, and you continue to gnaw who belongs that toy, remaining blind message from my gesture? Certainly, in the gesture of Kafka has a certain arrogance, but it is not the arrogance of the winner, it's the least arrogance of the defeated, the arrogance of the wise from the bottom. The gesture of Kafka is less humour of the director of the circus, and more humour of the clowns who have already pulled makeup.

Kafka is first great civilisation author who clearly states that man and works in the modern world have become objects, elements of nothingness, evidence of non-existence. According to the testimony of Janoah, Kafka said: "We are more object than a living being" (Kafka, 2011a: 128). As it progresses his diaries, so less Kafka himself describes the terms of a human being, less in terms of estranged or dead person, even less in terms of the animal (the decisions of the stories The Metamorphosis or The Burrow). Late Kafka has only one description of himself, he becomes a nice corpse to vultures towns, ham from the perfect supermarket. In the diary Kafka read his fantasy of "broad knife to butcher it quickly and with mechanical regularity cut into me by thin pieces (ham) flying" (Begley, 2008: 56), which Zelda Smith called it "a perfect piece Kafka ... Parma style, pezzi di Kafka "(Smith, 2008: 5).

Here is a brilliant prospect of the author, who, decades later, and in our historical time, really finished as kilogramme Kafka sold at auction Kilogramme Kafka for vultures of the city, which markets packed terms offered as food.

2. KAFKA, humorist

When we say that Kafka is humorist of the absurd, the question follows: Is it possible on the occasion of Kafka to talk about any humor? How can about the author of horrible terrifying meaninglessness, to attach any laughter?

Anyone who, like me, undertook to teach Kafka in universities' classrooms know that Kafka is almost impossible to teach. Kafka simply does not work in the classroom. And most charismatic lecturer, equipped with appropriate methodological arsenal, rarely manages to overcome the rejection by which students regularly respond to Kafka, the inability to transfer knowledge kilogramme Kafka on the "next generation." Kafka in my classroom most often caused anxiety, nausea and what specific sliding of meaning in our work as interpreters of literary works. Why is that? The work of Kafka's dramatic break with the logic of each micro-community (in the classroom, in the courtroom, the hospital, at the slaughterhouse) ... Students reject Kafka because they feel that Kafka breaks the social logic of the commons upon which classroom relies. Students intuitively feel that dialogue with Kafka is already some dialogue of the enemies, namely dialogue with someone who wants to set up a break in the dialogue. Kafka sometimes can really cause admiration, but it's always admiration mixed with disgust, admiration for someone, though still part of us, simultaneously is someone who erupted from the human circulation, someone who disputes the classroom. More than any other writer that I know, Kafka causes an interruption in the transfer of knowledge, resistance to Oedipal transmission of the human heritage, from older to younger, briefly - resistance to pedagogical tradition.

However, the acceptance of Kafka in the classroom is possible under one condition. From my humble experience, that is if Kafka in the classroom taught as philosophically meditative humorist. Kafka would not oppose this decision. The most beautiful pages of the biography of Max Brod, Kafka committed to remember when Kafka stopped before readers in Prague's round of Brod, which loudly laughed while he comically read the first chapter of Process. "They," said Max Brod, "laughed with unbridled laughter" (Deleuze and Guattari, 1998: 74). Before his listeners, Kafka performed as Charlie Chaplin, aware that his work can only be received through humour mode. He has performed as a clown who communicates truth in the pause of the battle between man and the lion, between the battle of acrobats and gravity. Kafka read his unfinished sketches as a fun interlude in which to denounce the whole grandiose representation of the world as a break while the circus administration changes mise-en-scene, to strain ropes next acrobat, it arranges decor of oriental East ... and only the lonely clown, whom audience mostly ignored, trying to turn the attention of irked and hungry viewers for blood. Just in that little pause and just a clown have permission to communicate the truth about the essence of things. But that truth is not true desires almost no one from the audience. Kafka was unaware that there in the theatre comedy exists those frightening dimensions of unshaped horror. Writing should be disclosure, writes Kafka, and thus define the theatre:

"In the theater come enemies, not the audience, strength is spent on secondary matters; from it at the end remains only effort, straining, and it is almost never begets quality. ... Therefore I not go to the theater. It's too sad"(Kafka, 2011a: 74).

The Circus, clownish mode in which Kafka had read his own creation in front of friends, paradoxically, is actually the most difficult tone to communicate the essence of things. Children with horror looking at the clownish person. Upset mother extracted weeping babies from the circus tents while clown performing. Thousands of people witnessed the horror that intimate feels of seeing the face of a clown in the condensed mixture of sadness and joy. Adult viewers mostly ignored irritant interlude of clowns. While in the arena, technicians placed the ropes for the next epic struggle of the trainer with the lion, for the next drama of the acrobat with the gravity, circus audience invariably endure the clown only for the award which he knows that will follow later, when they can see magnificent person who overcomes the lion, which tamed the snake, which overcomes gravity ... all subsequent points of the rank of the victory of the man ... in the epic game of the world, namely, man wins just because he learned to play in dishonest way, on unfair terrain and "rigged backdrops." We do not need much wisdom to realise that barehanded man could never beat the free, no-narcotised lion of prairie in an equal fight. While the circus was going great deception of the world, then the only clown has the most difficult task. The only clown with its small, small strokes must testify unto fundamental meaninglessness of the victory (which, if the viewer grasp in all its tragicomic dimension) will disintegrate precisely the meaning of the circus.

The American writer David Foster Wallace, who a few years ago has committed suicide and who was one of the last truly great inheritors of Kafkian's tradition in literature, in the brilliant text Laughing with Kafka (1998), also, pleaded to read Kafka as a humorist. Wallace said the big stories and good jokes have a common feature, are not information, but ex-formation (Wallace, 1998: 23). That good literature and a good joke are a vitality which escapes from signifying chains of information, which in shock effect of understanding happens suddenly, here and now, knowing that later causes paralysis of action. What I have yet to announce when Kafka telling his joke? The simple logic tells us that the easiest way to destroy the joke is to explain after it recounted. The same logic applies to Kafka: how to go further with the interpretation when the text of Kafka is already demystified by the logic of interpretation? Kafka does not work the traditional interpretation of symbols, decoding the 'semantic keys' in the plot and similar techniques which normally use for dismembering of the literary works. How to interpret the joke in Kafka? Kafka disliked literary theorists and critics, not tolerated literary machinery that chokes the text.

Moreover, Kafka stands outside the literary schools of stylistic directions. For various authors we can say that "written as" Kafka. Kafka himself might like to write as Robert Walser (the only author who truly admired). But certainly - can not on occasion Kafka to say: "A-ha, this story of Kafka-like Proust, like the Dostoevsky ...." As the joke can not say that it looks like another joke. The best joke is always singular, and if it is part of a series of similar jokes ( "go bear in the woods ..." or "little Mujo asks the teacher ..." or "Chuck Norris can ..."), then it is over strings of singular jokes they are not "talk" with other such jokes, because the real humor is a matter of first time, the creaking of the material, the resistance of the fabric, novelty that causing disruption of the public order, causing an earthquake in signifying chains, because it is unexpectedness and because it is like nothing before and after them. Likewise the stories of Kafka are singular creations. In them humor is dry; humour not based on a linguistic play or sexual allusion, nor on stylised effort. The characters in Kafka's are not ironic comments on the characters from the previous literature. Kafka's characters are absurd and frightening and sad and singular - his characters exist only in the literary world and come out of nowhere. Therefore, the humor of Kafka is furthest from the humor of sitcoms, for example, just as it is not a humor of blessed riddles and or coarse insinuations, nor is the so-called humor of the situation ( "the husband moved the bed and under saw him, the naked lover") - it is too barbaric for Kafka, but that does not mean that Kafka harbored a subtle humor. Rather, quite the opposite - the humour of Kafka is dry and clean and above all anti (subtle) humour.

to be continued ...

Translated from: http://www.jasnakoteska.blogspot.com/ by Dejan Stojkovski