|

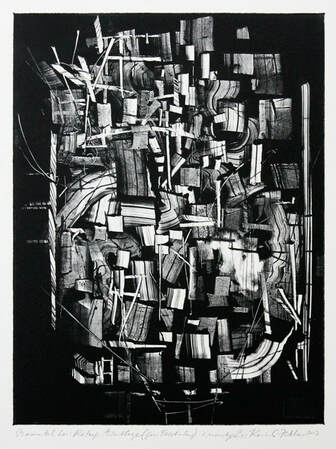

by Ian Buchanan Kevin Fletcher - ornamental low relief assemblage AbstractIf the development of assemblage theory does not need to be anchored in the work of Deleuze and Guattari, as increasingly seems to be the case in the social sciences, then cannot one say that the future of assemblage theory is an illusion? It is an illusion in the sense that it continues to act as though the concept was invented by Deleuze and Guattari, but because it does not feel obligated to draw on their work in its actual operation or development, it cannot lay claim to being authentic. That this does not trouble certain scholars in the social sciences is troubling to me. So in this paper I offer first of all critique of this illusory synthetic version of the assemblage and accompany that with a short case study showing what can be gained by returning to Deleuze and Guattari. Keywords: assemblage theory, ontology of policy, infrastructure policy, actant, agencement, indigenous housing I. Assemblage as ‘Received Idea’One cannot help but wonder how different the uptake of Deleuze and Guattari’s concept of ‘agencement’ would be if it had not been translated as ‘assemblage’ and an alternate translation such as ‘arrangement’ (which is my preferred translation [Buchanan 2015: 383]) had become the standard? It may be that assemblage theory as we know it today would never have taken off, which would be a pity because the field is enormously productive and it has brought into its orbit a huge range of questions and problematics that might otherwise never have been considered. But at least we would not be faced with the problem of how to ‘re-think’ a concept that has all but become a ‘received idea’ (as Flaubert put it), that is, an idea that is so well understood it no longer bears thinking about in any kind of critical way. Unfortunately, the consensus understanding of the concept has been shaped as much (if not more than) by a plain language understanding of the English word ‘assemblage’ as it has by any deep understanding of the work of Deleuze and Guattari. This is particularly evident in the social sciences where there is a strong and–I will argue–undue emphasis on the idea of ‘assembling’ as the core process of assemblages. This is compounded by an apparent consensus that assemblage theory is one of those concepts like deconstruction and postmodernism that no longer owes its development to a specific authorial source. While it is hard to fault the latter view in that one should be free to re-make concepts, its detachment from Deleuze and Guattari’s thinking has led to a considerable loss of clarity and cohesion in the concept.1 The fact that the English word ‘assemblage’ is not Deleuze and Guattari’s own word, but an artefact of translation, is rarely, if ever, brought into consideration, and where it is it tends to be dismissed as unimportant, which perhaps explains the emphasis on assembling as the central concern of assemblage theory. There are a number of problems with this view of things, not least the fact that assemblage in English does not mean the same thing as agencement in French. Not only that, it is itself a loan word from French, thus adding to the confusion. As Thomas Nail (among others) has shown, agencement derives from agencer, which according to Le Robert & Collins means ‘to arrange, to lay out, or to piece together’, whereas assemblage means ‘to join, to gather, to assemble’ (Nail 2017: 22; but see also Buchanan 2015: 383). The difference between these two definitions is perhaps subtle, but by no means inconsequential: we might say the former is a process of composition whereas the latter is one of compilation; the difference being that one works with a pre-existing set of entities and gives it a different order, whereas the latter starts from scratch and builds up to something that may or may not have order. A compilation may be a‘ heap of fragments’, where as a composition cannot be.2 The solution, however, is not as simple as insisting that Deleuze and Guattari should (or as some would have it, can) only be read in the ‘original’ French, which is not practical for all readers in any case, because, as I will show, this same plain language approach also applies to straightforward terms like ‘multiplicity’ and ‘territory’. The solution, in my view, is to ‘return’ to Deleuze and Guattari’s work. I will take as my case in point an essay by two human geographers,Tom Baker and Pauline McGuirk, ‘Assemblage Thinking as Methodology: Commitments and Practices for Critical Policy Research’ (2016), one of the richest, most comprehensive and sophisticated accounts of assemblage theory as it is deployed in the social sciences yet written, and therefore a perfect and anything but ‘straw man’ example of the kind of work I am talking about. In spite of its considerable sophistication, it has completely detached the concept of assemblage from Deleuze and Guattari and replaced it with a synthetic accumulation of readings of readings of Deleuze and Guattari. Ironically, the kind of genealogical reading Baker and McGuirk say is part and parcel of assemblage thinking is completely absent from their own use of the concept. Instead of tracing the concept back to a point of origin, they pull together a heterogeneous ensemble of quotes about the concept of the assemblage from a vast trawl-through of the secondary literature. It is therefore unsurprising, but telling that in defining the concept of Deleuze and Guattari, or DeLanda’ (Baker and McGuirk 2016: 15, n.1). Without any anchor in Deleuze and Guattari’s work the concept floats off into an alternate universe in which all contributions to the discussion are treated as equally valuable and there is no arbitration between the strong and the weak versions, never mind the accurate and the wrong versions.the assemblage Baker and McGuirk do not refer to the work of Deleuze and Guattari, which is mentioned but not cited. In a footnote they clarify that for their purposes ‘assemblage thinking refers to a diverse set of research accounts that may or may not engage directly with formal theories of assemblage, such as those of Deleuze and Guattari, or DeLanda’ (Baker and McGuirk 2016: 15, n.1). Without any anchor in Deleuze and Guattari’s work the concept floats off into an alternate universe in which all contributions to the discussion are treated as equally valuable and there is no arbitration between the strong and the weak versions, never mind the accurate and the wrong versions. Baker and McGuirk define the ‘assemblage as a “gathering of heterogeneous elements consistently drawn together as an identifiable terrain of action and debate”’ (drawing on the work of Tanya Li), noting that its elements include ‘arrangements of humans, materials, technologies, organizations, techniques, procedures, norms, and events, all of which have the capacity for agency within and beyond the assemblage’ (Baker and McGuirk 2016: 4). They also say, citing J. Macgregor Wise, that the assemblage ‘claims a territory’, and that it ‘is realized through ongoing processes of deterritorialization and reterritorialization, such that assemblages are continually in the process of being made and remade’ (4). To which they add Colin McFarlane’s suggestion that the ‘popularity of assemblage results in large part from its understanding of the social as “materially heterogeneous, practice based, emergent and processual”’ (4). For Baker and McGuirk the assemblage is primarily a ‘methodological-analytical framework’ so ‘its application demands an explicitly methodological discussion’, something which in their view is sorely lacking in the literature (Baker and McGuirk 2016: 4, 5). This is the most important (and frustrating) part about Baker and McGuirk’s project. While I do not agree with the particulars of their way of constructinga ‘ methodological-analytical framework ’ out of the concept of the assemblage, I nonetheless support very strongly the necessity of so doing.I would add that in my view explicitly methodological discussions of the assemblage are sorely lacking in the secondary Deleuze and Guattari literature too. It is to the particulars of Baker and McGuirk’s ‘methodological-analytical framework’ that I now want to turn. They write: Assemblage methodologies are guided by epistemological commitments that signify a certain interrogative orientation toward the world. Though abstract, these commitments inform inclusions, priorities, and sensitivities, which together constitute the field of vision brought to bear on empirical phenomena. Sifting through the substantial number of accounts using assemblage thinking [note again the fact they do not refer to Deleuze and Guattari], we can identify four commitments common to those using assemblage methodologically. These are commitments to revealing multiplicity, processuality, labour, and uncertainty. (Baker and McGuirk 2016: 6; my emphasis) As I will show, the detachment from Deleuze and Guattari’s work seems to compel a plain language approach which, to borrow a term from translation studies, puts them at the mercy of several ‘false friends’, that is, words that look like they should mean one thing but in fact mean something else. Commitment to multiplicity is, for Baker and McGuirk, an interpretive strategy for setting aside the presumption of coherence and determination that reigns in certain quarters of contemporary policy studies. It holds to the idea that all social and cultural phenomena are multiply determined and cannot be reduced to a single logic. More particularly, in a policy context, it points to ‘the practical coexistence of multiple political projects, modes of governance, practices and outcomes’ (Baker and McGuirk 2016: 6–7). This means policy outcomes cannot be linked in a linear way to a specific determination, but have to be treated as contingent, or, at any rate, indirect. There are three problems here: firstly, we have to be careful not to conflate the content (policy) with the form (assemblage) because however incoherent a policy formation may be in the eyes of its critics, as an assemblage it must as a matter of necessity tend towards coherence, that being one of its essential functions (the problem of unity and diversity is central to Deleuze and Guattari’s account of the assemblage [Deleuze and Guattari 1987: 43–5]). Secondly, the assemblage is a multiplicity, but this does not mean it is multiply determined. It refers to a state of being, not its actual process of composition, and there is no reason at all why it cannot have a single or singular logic.3 Thirdly, while it is true assemblages are contingent, their outputs are not. Indeed, what would be the point of the concept if this was the case? As Deleuze and Guattari say, given a certain effect, what kind of machine (assemblage) is capable of producing it? (Deleuze and Guattari 1983: 3.) The commitment to multiplicity is enacted via a second commitment to what they call processuality, which Baker and McGuirk define (again borrowing liberally from a diverse body of secondary literature) as what happens in an assemblage. At first glance they seem to be saying assemblages assemble, that they draw together disparate elements and combine them in a provisional fashion; they may tend towards stabilisation, or not, but regardless exist in a state of constant flux: In methodological terms, a focus on the processes through which assemblages come into and out of being lends itself to careful genealogical tracing of how past alignments and associations have informed the present and how contemporary conditions and actants are crystallizing new conditions of possibility. (Baker and McGuirk 2016: 7) But as this quote makes clear, something quite different is meant by processuality. It names, rather, a concern for genesis–but how something comes together and how it operates once it does are quite different issues (Deleuze and Guattari 1987: 152). But that is not the only problem here. One wonders how this interpolation of what I assume is Foucault’s concept of genealogy (rather than Nietzsche’s, or even Deleuze’s version of Nietzsche) can be squared with the aforementioned commitment to non-linearity? More importantly, though, the whole idea of a genealogy of the assemblage stands in flat contradiction of Deleuze and Guattari’s account of the assemblage, which is focused on the question ‘how does it work?’ and not ‘what does it mean?’ much less ‘where does it come from?’ (Deleuze and Guattari 1983: 109).4 The commitment to revealing the labour needed to produce and maintain assemblages is said by Baker and McGuirk to echo Deleuze and Guattari’s ‘original term agencement–roughly meaning “putting together” or “arrangement”–later translated to assemblage’ (Baker and McGuirk 2016:7), but in fact it echoes the plain language understanding of assemblage as the putting together of things, as their subsequent clarifications of this point make apparent. They go on to say, again borrowing widely, assemblages ‘are not accidental, but knowingly and unknowingly held together’ and they ‘are always coming apart as much as coming together, so their existence in particular configurations is something that must be continually worked at’ (7). Ultimately, what this commitment reveals is that ‘policy and policy-making [is] a laboured over achievement’ (8). Without wishing to dispute their conclusion here–there can be no doubt policy and policy-making is a laboured over achievement–I do want to say for the sake of understanding the concept of the assemblage that the labour required to sustain a particular instance of an assemblage is a kind of local area problem that should not be confused with the actual operation of the concept itself. The assemblage itself is, by definition, self-sustaining: it requires labour to actualise it, to be sure, but its existence does not depend on that labour. There is constant slippage between what we might call actually existing assemblages and the concept of the assemblage in Baker and McGuirk’s account such that the former tends to stand in the place of the latter and the difference between the two vanishes. When that happens the concept becomes adjectival rather than analytical, it describes rather than defamiliarises, which defeats the purpose of having the concept in the first place. The fourth and final commitment is to uncertainty and the temptation to know too much. ‘Such a position involves accepting that, rather than producing Archimedean accounts of the world “as it is”, social research can only produce situated readings and, therefore, must make modest claims’(Baker and McGuirk 2016:8). Interestingly, this is not something Deleuze and Guattari advocated. In fact, they argued for precisely the opposite view: as they put it, the only problem with abstraction is that we are not abstract enough. One cannot arrive at the assemblage by means of a situated account because the contents of an assemblage do not necessarily disclose the form of an assemblage; similarly, we need to be wary of assigning every local variety of anassemblage an independent identity distinct from the abstract assemblage. Paradoxically, there is no surer way of winding up in the ‘knowing too much’ space that assemblage thinking is supposed to avoid than the approach Baker and McGuirk recommend because such self-limiting analyses presume to know in advance what knowing enough and therefore what knowing too much looks like. It is precisely this kind of analytic cul-de-sac that Deleuze and Guattari were trying to avoid by saying we need to be experimental in our approach. What many readers find infuriating in their work is precisely their blatant refusal to stick to making modest claims.On the contrary, they make bold, global claims and in the process force us to think differently about the world. to be continued ... taken from:

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Steven Craig Hickman - The Intelligence of Capital: The Collapse of Politics in Contemporary Society

Steven Craig Hickman - Hyperstition: Technorevisionism – Influencing, Modifying and Updating Reality

Archives

April 2020

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed