|

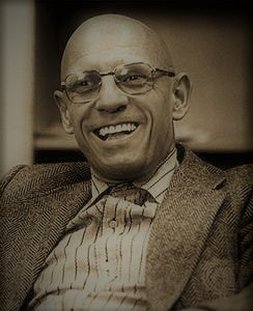

by Michel Foucault

An expression which was important in the eighteenth century captures this very well: Quesnay speaks of good government as 'economic government'. This latter notion becomes tautological, given that the art of government is just the art of exercising power in the form and according to the model of the economy. But the reason why Quesnay speaks of 'economic government' is that the word 'economy', for reasons that I will explain later, is in the process of acquiring a modern meaning, and it is at this moment becoming apparent that the very essence of government - that is, the art of exercising power in the form of economy - is to have as its main objective that which we are today accustomed to call 'the economy'.

loading...

The word 'economy', which in the sixteenth century signified a form of government, comes in the eighteenth century to designate a level of reality, a field of intervention, through a series of complex processes that I regard as absolutely fundamental to our history.

The second point which I should like to discuss in Guillaume de La Perriere 's book consists of the following statement: 'government is the right disposition of things, arranged so as to lead to a convenient end'.

I would like to link this sentence with another series of observations. Government is the right disposition of things. I would like to pause over this word 'things', because if we consider what characterizes the ensemble of objects of the prince 's power in Machiavelli, we will see that for Machiavelli the object and, in a sense, the target of power are two things, on the one hand the territory, and on the other its inhabitants. In this respect, Machiavelli simply adapted to his particular aims a juridical principle which from the Middle Ages to the sixteenth century defined sovereignty in public law: sovereignty is not exercised on things, but above all on a territory and consequently on the subjects who inhabit it. In this sense we can say, that the territory is the fundamental element both in Machiavellian principality and in juridical soveregnity as defined by the theoreticians and philosoehers of right. Obviously enough, these territories can be fertile or not, - the population dense or sparse, the inhabitants rich or poor, active or lazy, but all these elements are mere variables by comparison with territory itself, which is the very foundation of principality and sovereignty. On the contrary, in La Perriere's text, you wiil notice-that-the, definition of government in no way refers to territory. (One governs things) But what does this mean? I do not think this is a matter of opposing things to men, but rather of showing that what government has to do with is not territory but rather a sort of complex composed of men and things. The things with which in this sense government is to be concerned are in fact men, 'but men in their relations, their links, their imbrication with those others which are wealth, resources, means of subsistance, the territory with its specifk qualities, climate, irritgration, fertility, etc.; men in their relation to that other kind of things, cust0ms, habits, ways of acting and thinking, etc. lastly man in their-relation to that other kind of things. accidents and misfortnus such as famine. epidemics. death, etc. The fact that government concerns things understood in this way, this imbrication of men and things, is I believe readily confirmed by the metaphor which is inevitably invoked in these treatises on government, namely that of the ship. What does it mean to govern a ship? It means clearly to take charge of the sailors, but also of the boat and its cargo; to take care of a ship means also to reckon with winds, rocks and storms; and it consists in that activity of establishing a relation between the sailors who are to be taken care of and the ship which is to be taken care of, and the cargo which is to be brought safely to port, and all those eventualities like winds, rocks, storms and so on; this is what characterizes the government of a ship. The same goes for the running of a household. Governing a household, a family, does not essentially mean safeguarding the family property; what concerns it is the individuals that compose the family, their wealth and prosperity. It means to reckon with all the possible events that may intervene, such as births and deaths, and with all the things that can be done, such as possible alliances with other families; it is this general form of management that is characteristic of government; by comparison, the question of landed property for the family, and the question of the acquisition of sovereignty over a territory for a prince, are only relatively secondary matters. What counts essentially is this complex of men and things; property and, territory are merely one of its variables.

This theme of the government of things as we find it in La Perriere can also be met with in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. Frederick the Great has some notable pages on it in his Anti-Machiavel. He says, for instance, let us compare Holland with Russia: Russia may have the largest territory of any European state, but it is mostly made up of swamps, forests and deserts, and is inhabited by miserable groups of people totally destitute of activity and industry; if one takes Holland, on the other hand, with its tiny territory, again mostly marshland, we find that it nevertheless possesses such a population, such wealth, such commercial activity and such a fleet as to make it an important European state, something that Russia is only just beginning to become.

To govern, then, means to govern things. Let us consider once more the sentence I quoted earlier, where La Perriere says: 'government is the right disposition of things, arranged so as to lead to a convenient end'. Government, that is to say, has a finality of its own, and in this respect again I believe it can be clearly distinguished from sovereignty. I do not of course mean that sovereignty is presented in philosophical and juridical texts as a pure and simple right; no jurist or, a fortiori, theologian ever said that the legitimate sovereign is purely and simply entitled to exercise his power regardless of its ends. The sovereign must always, if he is to be a good sovereign, have as his aim, 'the common welfare and the salvation of all'. Take for instance a late seventeenth-century author. Pufendorf says: 'Sovereign authority is conferred upon them [the rulers] only in order to allow them to use it to attain or conserve what is of public utility'. The ruler may not have consideration for anything advantageous for himself, unless it also be so for the state. What does this common good or general salvation consist of, which the jurists talk about as being the end of sovereignty? If we look closely at the real content that jurists and theologians give to it, we can see that 'the common good' refers to a state of affairs where all the subjects without exception obey the laws, accomplish the tasks expected of them, practise the trade to which they are assigned, and respect the established order so far as this order conforms to the laws imposed by God on nature and men: in other wordst, the common good' means essential obedience to the law, either that of their earthly sovereign ot that God, the absolute sovereign. In every case, what characterizes the end of sovereignty, ihis common and general good, is in sum nothing other than submission to sovereignty. This means that the end of sovereignty is circular: the end of sovereignty is the exercise of sovereignty. The good is obedience to the law, hence the good for sovereignty is that people should obey it. This is an esential circularity which, whatever its theoretical structure, moral justification or practical effects, comes very close to what Machiavelli said when he stated that the primary aim of the prince was to retain llis principality. We always come back to this self-referring circularity of sovereignty or principality.

Now, with the new definition given by La Perriere, with his attempt at a definition of government, I believe we can see emerging a new kind of finality. Government is defined as a right manner of disposing things so as to lead not to the form of the common good, as the jurists' texts would have said, but to an end which is 'convenient' for each of the things that are to be governed. This implies a plurality of specific aims: for instance, government will have to ensure that the greatest possible quantity of wealth is produced, that the people are provided with sufficient means of subsistence, that the population is enabled to multiply, etc. There is a whole series of specific finalities, then, which become the objective of government as such. In order to achieve these various finalities, things must be disposed - and this term, dispose, is important because with sovereignty the instrument that allowed it to achieve its aim - that is to say, obedience to the laws - was the law itself; law and sovereignty were absolutely inseparable. On the contrary, with government it is a question not of imposing law on men, but of disposing things: that is to say, of employing tactics rather than laws, and even of using laws themselves as tactics - to arrange things in such a way that, through a certain number of means, such and such ends may be achieved.

I believe we are at an imporatant turning point here: whereas the end of sovereignty is internal to itself and possesses its own intrinsic instruments in the shape of its laws, the finarlity of government resides in the things it menages and it pursuit of the perfection and intensification of the processes which-it directs; and the instruments of goverment, instead of being laws, now come to be a range or multiform tactics. Within perspective of government, law is not what is important: this is a frequent theme throughout the seventeenth century, and it is made explicit in the eighteenth century texts of the Physiocrats which explain that it is not through law that the aims of government are to be reached.

Finally, a fourth remark, still concerning this text from La Perri ere: he says that a good ruler must have patience, wisdom and diligence. What does he mean by patience? To explain it, he gives the example of the king of bees, the bumble-bee, who, he says, rules the bee-hive without needing a sting; through this example God has sought to show us in a mystical manner that the good governor does not have to have a sting, that is to say, a weapon of killing, a sword - in order to exerclse - liis power; he must have patience rather than wrath, and it is not the right to kill, to employ force, that forms the essence of the figure of the governor. And what positive content accompanies this absence of sting? Wisdom and diligence. Wisdom, understood no longer in the traditional sense as knowledge of divine and human laws, of justice and equality, but rather as the knowledge of things, of the objectives that can and should be attained, and the disposition of things required to reach them; it is this knowledge that is to constitute the wisdom of the sovereign. As for his diligence, this is the principle that a governor should only govern in such a way that he thinks and acts as though he were in the service of those who are governed. And here, once again, La Perriere cites the example of the head of the family who rises first in the morning and goes to bed last, who concerns himself with everything in the household because he considers himself as being in its service. We can see at once how far this characterization of government differs from the idea of the prince as found in or attributed to Machiavelli. To be sure, this notion of governing, for all its novelty, is still very crude here.

This schematic presentation of the notion and theory of the art of government did not remain a purely abstract question in the sixteenth century, and it was not of concern only to political theoreticians. I think we can identify its connections with political reality. The theory of the art of government was linked, from the sixteenth century, to the whole development of the administrative apparatus of the territorial monarchies, the emergence of governmental apparatuses; it was also connected to a set of analyses and forms of knowledge which began to develop in the late sixteenth century and grew in importance during the seventeenth, and which were essentially to do with knowledge of the state, in all its different elements, dimensions and factors of power, questions which were termed precisely 'statistics', meaning the science of the state; finally, as a third vector of connections, I do not think one can fail to relate this search for an art of government to mercantilism and the Cameralists' science of police.

To put it very schematically, in the late sixteenth century and early seventeenth century, the art of government finds its first form of crystallization, organized around the theme of reason of state, understood not in the negative and pejorative sense we give to it today (as that which infringes on the principles of law, equity and humanity in the sole interests of the state), but in a full and positive sense: the state is governed according to rational principles which are intrinsic to it and which cannot be derived solely from natural or divine laws or the principles of wisdom and prudence; the state, like nature, has its own proper form of rationality, albeit of a different sort. Conversely, the art of government, instead of seeking to found itself in transcendental rules, a cosmological model or a philosophico-moral ideal, must find the principles of its rationality in that which constitutes the specific reality of the state. In my subsequent lectures I will be examining the elements of this first form of state rationality. But we can say here that, right until the early eighteenth century, this form of 'reason of state' acted as a sort of obstacle to the development of the art of goverment.

This is for a number of reasons. Firstly, there are the strictly historical ones, the series of great crises of the seventeenth century: first the Thirty Years War with its ruin and devastation; then in the mid-century the peasant and urban rebellions; and finally the financial crisis, the crisis of revenues which affected all Western monarchies at the end of the century. The art of government could only spread and develop in subtlety in an age of expansion, free from the great military, political and economic tensions which afflicted the seventeenth century from beginning to end. Massive and elementary historical causes thus blocked the propagation of the art of government. I think also that the doctrine formulated during the sixteenth century was impeded in the seventeenth by a series of other factors which I might term, to use expressions which I do not much care for, mental and institutional structures. The preeminence of the problem of the exercise of sovereignty, both as a theoretical question and as a principle of political organization, was the fundamental factor here so long as sovereignty remained the central question. So long as the institutions of sovereignty were the basic political institutions and the exercise conceived as an-exercise of sovereignty, the art of government could not be developed in a specific and autonomous manner. I think we have a good example of this in mercantilism. Mercantilism might be described as the first sanctioned efforts to apply this art of government at the level of political practices and knowledge of the state; in this sense one can in fact say that mercantilism represents a first threshold of rationality in this art of government which La Perriere's text had defined in terms more moral than real. Mercantilism is the first rationalization of the exercise of power as a practice of government; for the first time with mercantilism we see the development of a savoir of state that can be used as a tactic of government. All this may be true, but mercantilism was blocked and arrested, I believe, precisely by the fact that it took as its essential objective the might of the sovereign; it sought a way not so much to increase the wealth of the country as to allow the ruler to accumulate wealth, build up his treasury and create the army with which he could carry out his policies. And the instruments mercantilism used were laws, decrees, regulations: that is to say, the traditional weapons of sovereignty. The objective was sovereign's might, the instruments those of sovereignty: mercantilism sought to reinsert the possibilities opened up by a consciously conceived art of government within a mental and institutional structure, that of sovereignty, which by its very nature stifled them.

Thus, throughout the seventeenth century up to the liquidation of the themes of mercantilism at the beginning of the eighteenth, the art of government remained in a certain sense immobilized. It was trapped within the inordinately vast, abstract, rigid framework of the problem and institution of sovereignty. This art of government tried, so to speak, to reconcile itself with the theory of sovereignty by attempting to derive the ruling principles of an art of government from a renewed version of the theory of sovereignty - and this is where those seventeenth-century jurists come into the picture who formalize or ritualize the theory of the contract. Contract theory enables the founding contract, the mutual pledge of ruler and subjects, to function as a sort of theoretical matrix for deriving the generaL principle of an art of goverment. But although contract theory: with its reflection on the relations up between ruler and subjects, played a very important role in theories of public law, in practice, as is evidenced by the case of Hobbes (even though what Hobbes was aiming to discover was the ruling principles of an art of government), it remained at the stage of the formulation of general principles of public law.

On the one hand, there was this framework of sovereignty which was too large, too abstract and too rigid; and on the other, the theory of government suffered from its reliance on a model which was too thin, too weak and too insubstantial, that of the family: an economy of enrichment still based on a model of the family was unlikely to be able to respond adequately to the importance of territorial possessions and royal finance.

How then was the art of government able to outflank these obstacles? Here again a number of general processes played their part: the demographic expansion of the eighteenth century, connected with an increasing abundance of money, which in turn was linked to the expansion of agricultural production through a series of circular processes with which the historians are familiar. If this is the general picture, then we can say more precisely that the art of government found fresh outlets through'the emergence of the problem of population; or let us say rather that there occurred a subtle process, which we must seek to reconstruct in its particulars, through which the science of government, the recentring of the theme of economy on a different plane from that of the family, and the problem of population are all interconnected.

It was through the development of the science of government that the notion of economy came to be recent red on to that different plane of reality which we characterize today as the 'economic ', and it was also through this science that it became possible to identify problems specific to the population; but conversely we can say as well that it was thanks to the perception of the specific problems of the population, and thanks to the isolation of that area of reality that we call the economy, that the problem of government finally came to be thought, reflected and calculated outside of the juridical framework of sovereignty. And that 'statistics' which, in mercantilist tradition, only ever worked within and for the benefit of a monarchical administration that functioned according to the form of sovereignty, now becomes the major technical factor, or one of the major technical factors, of this new technology.

In what way did the problem of population make possible the derestriction of the art of government? The perspective of population, the reality accorded to specific phenomena of population, render possible the final elimination of the model of the family and the recentring of the notion of economy. Whereas statistics had previously worked within the administrative frame and thus in terms of the functioning of sovereignty, it now gradually reveals that population has its own regularities, its own rate of deaths and diseases, its cycles of scarcity, etc.; statistics shows also that the domain of population involves a range of intrinsic, aggregate effects, phenomena that are irreducible to those of the family, such as epidemics, endemic levels of mortality, ascending spirals of labour and wealth; lastly it shows that, through its shifts, customs, activities, etc., population has specific economic effects: statistics, by making it possible to quantify these specific phenomena of population, also shows that this specificity is irreducible to the dimension of the family. The latter now disappears as the model of government, except for a certain number of residual themes of a religious or moral nature. What, on the other hand, now emerges into prominence is the family considered as an element internal to population, and as a fundamental instrument in its government.

In other words, prior to the emergency of population, it was impossible to conceive the art of government except on the model of the familly terms of economy concieved, as the management of a famIly; from the moment when, on the contrary, population apears absoluteiy irreducible to the family, the latter become population, as an element internal to population: no longer, that is to say, a model, but a segment. Nevertheless it remains a privileged segment, because whenever information is required concerning the population, (sexual behaviour, demography, consumption, etc.), it has to be obtained through the family. But the family becomes an instrument rather than a model: the privileged instrument for the government of the population and not the chimerical model of good goverment. This shift from the level of the model to that of an instrument is, I believe, absolutdly .fundamental, and it is from the middle of the eighteenth century that the family appears in this dimension of instrumentality relative to the population, with the institution of campaigns to reduce mortalIty and to promote marriages, vaccinations, etc. Thus, what makes it possible f9f the theme of population to unblock the field of the art of government is this elimination of the family as model.

In the second place, population comes to appear above all else as the ultimate end of government. In contrast to sovereignty, government has as its purpose not the act of government itself, but the welfare of the population, the improvement of its condition, the increase of its wealth, longevity, health, etc.; and the means that the government uses to attain these ends are themselves all in some sense immanent to the population; it is the population itself on which government will act either directly through large-scale campaigns, or indirectly through techniques that will make possible, without the full awareness of the people, the stimulation of birth rates, the directing of the flow of population into certain regions or activities, etc. The population now represents more the end of government than the power of the sovereign; the population is the subject of needs, of aspirations, but it is also the object in the hands of the government, aware, vis-a-vis the government, of what it wants, but ignorant of what is being done to it. Interest at the level of the conciousness of each individual who goes to'make up the population,and interest considered as the interest of tne population regardless of what the particular interests and aspirations may be or the individuals, who compose it, this is the new target and the fundamental instrument of the government of population: the birth of a new art, or at any rate of a range of absolutely new tactics and techniques.

Lastly, population is the point around which is organized what in sixteenth-century texts came to be called the patience of the sovereign, in the sense that the population is the object that government must take into account in all its observations and savoir, in order to be able to govern effectively in a rational and conscious manner. The constitution of a savoir of government is absolutely inseparable from that of a knowledge of all the processes related to population in Its larger sense: that is to say, what we now call the economy. I said in my last lecture that the constitution of political economy depended upon the emergence from among all the various elements of wealth of a new subject: population. The new science caned poiitlcal economy arises out of the perception of new networks of continuous and multiple relations between population, territory and wealth; and this is accompanied by the formation of a type of intervention characteristic of government, namely intervention in the field of economy and population. In other words, the transition which takes place in the eighteenth century from an art of government to a political science, from a regime dominated by structures of sovereignty to one ruled by techniques of government, turns on the theme of population and hence also on the birth of political economy.

This is not to say that sovereignty ceases to play a role from the moment when the art of government begins to become a political science; I would say that, on the contrary, the problem of sovereignty was never posed with greater force than at this time, because it no longer involved, as it did in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, an attempt to derive an art of government from a theory of sovereignty, but instead, given that such an art now existed and was spreading, involved an attempt to see what juridical and institutional form, what foundation in the law, could be given to the sovereignty that characterizes a state. It suffices to read in chronological succession two different texts by Rousseau. In his Encyclopaedia article on 'Political economy', we can see the way in which Rousseau sets up the problem of the art of government by pointing out (and the text is very characteristic from this point of view) that the word 'oeconomy' essentially signifies the management of family properrty by the father, but that this model can no longer be accepted, even if it had been valid in the past; today we know, says Rousseau, that political economy is not the economy of the family, and even without making explicit reference to the Physiocrats, to statistics or to the general problem of the poplliation, he sees quite clearly this turning point consisting in the fact that the economy of 'political economy' has a totally' new sense which cannot be reduced to the old model of the, family, He undertakes in this article' the task of giving a new definition of the art of government. Later he writes The Social Contract, where he poses the problem of how it is possible, using concepts like nature, contract and general will, to provide a general principle of goverment which allows, room both for a juridical principle of sovereigiIty and for the elements through which an art of government can be defined and characterized. Consequently, sovereignty is far from being eliminated by the emergence of a new art of government, even by one which has passed the threshold of political science; on the contrary, the problem of sovereignty is made more acute than ever.

As for discipline, this is not eliminated either; clearly its modes of organization, all the institutions within which it had developed in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries - schools, manufactories, armies, etc. - all this can only be understood on the basis of the development of the great adminis.trative monarchies, but nevertheless, discipline was never more important or more valorized than at the moment when it became important to manage a population; the managing of a population not only concerns the collective mass of phenomena, the level of its aggregate effects, it also implies the management of population in its depths and its details. The notion of a government of population renders all the more acute the problem of the foundation of sovereignty (consider Rousseau) and all the more acute equally the necessity for the development of discipline (consider all the history of the disciplines, which I have attempted to analyze elsewhere).

Accordingly, we need to see things not in terms of the replacement of a society of sovereignty by a disciplinary society and the subsequent replacement of a _disciplinary society by a society of government; in reality one has a triangle, sovereignty-discipline-government, which has as its primary target the population and as its essential mechanism the apparatuses of security. In any case, I wanted to demonstrate the deep historical link between the movement that overturns the constants of sovereignty in consequence of the problem of choices of government, the movement that brings about the emergence of population as a datum, as a field of intervention and as an objective of governmental techniques, and the process which isolates the economy as a specific sector of reality, and political economy as the science and the technique of intervention of the government in that field of reality. Three movements: government, population, p0litical economy, which constitute from the eighteenth century onwards a solid seres, one which even today has assuredly not been dissolved.

In conclusion I would like to say that on second thoughts the more exact title I would like to have given to the course of lectures which I have begun this year is not the one I originally chose, 'Security, territory and population': what I would like to undertake is something which I would term a history of 'governmentality'. By this word I mean three things:

1. The ensemble formed by the institutions, procedures, analyses and reflections, the calculations and tactics that allow the exercise of this very specific albeit complex form of power, which has as its target population, as its principal form of knowledge political economy, and as its essential technical means apparatuses of security.

2. The tendency which, over a long period and throughout the West, has steadily led towards the pre-eminence over all other forms (sovereignty, discipline, etc.) of this type of power which may be termed government, resulting, on the one hand, in the formation of a whole series of specific governmental apparatuses, and, on the other, in the development of a whole complex of savoirs.

3. The process, or rather the result of the process, through which the state of justice of the Middle Ages, transformed into the administrative state during the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, gradually becomes 'governmentalized'.

We all know the fascination which the love, or horror, of the state exercises today; we know how much attention is paid to the genesis of the state, its history, its advance, its power and abuses, etc. The excessive

value attributed to the problem of the state is expressed, basically, in two ways: the one form, immediate, affective and tragic, is the lyricism of the monstre froid we see confronting us; but there is a second way of overvaluing the problem of the state, one which is paradoxical because apparently reductionist: it is the form of analysis that consists in reducing the state to a certain number of functions, such as the development of productive forces and the reproduction of relations of production, and yet this reductionist vision of the relative importance of the state's role nevertheless invariably renders it absolutely essential as a target needing to be attacked and a privileged position needing to be occupied. But the state, no more probably today than at any other time in its history, does not have this unity, this individuality, this rigorous functionality, nor, to speak frankly, this importance; rnaybe, after all, the state is no more than a composite reality and a mythicized abstraqion, whose importance is a lot more limited than many of us think. Maybe what is really important for our modernity - that is, for our present, - is not so much the etatision of society, as the govermentalization of the state.

We live in the era of a 'governmentality' first discovered in the eighteenth century. This governmentalization of the state is a singularly paradoxical phenomenon, since if in fact the problems of governmentality and the techniques of government have become the only political issue, the only real space for political struggle and contestation, this is because the governmentalization of the state is at the same time what has permitted the state to survive, and it is possible to suppose that if the state is what it is today, this is so precisely thanks to this governmentality, which is at once internal and external to the state, since it is the tactics of government which make possible the continual definition and redefinition of what is within the competence of the state and what is not, the public versus the private, and so on; thus the state can only be understood in its survival and its limits of the basis of the general tactics of governmentality.

And maybe we could even, albeit in a very global, rough and inexact fashion, reconstruct in this manner the great forms and economies of power in the West. First of all, the state of justice, born in the feudal type of territorial regime which corresponds to a society of laws - either customs or written laws - involving a whole reciprocal play of obligation and litigation; second, the administrative state, born in the territoriality of national boundaries in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries and corresponding to a society of regulation and discipline; and finally a governmental state, essentially defined no longer in terms of its territoriality, of its surface area, but in terms of the mass of its population with its volume and density, and indeed also with the territory over which it is distributed, although this figures here only as one among its component elements. This state of government which bears essentially on population and both refers itself to and makes use of the instrumentation of economic savoir could be seen as corresponding to a type of society controlled by apparatuses of security.

In the following lectures I will try to show how governmentality was born out of, on the one hand, the archaic model of Christian pastoral, and, on the other, a diplomatic-military technique, perfected on a European scale with the Treaty of Wesphalia; and that it could assume the dimensions it has only thanks to a series of specific instruments, whose formation is exactly contemporaneous with that of the art of government and which are known, in the old seventeenth- and eighteenth-century sense of the term, as police. The pastoral. the new diplomatic-military techniques and, lastly, police: these are the three-elerments that I believe made possible the production of this fundamental phenomenon in Western history, the governmentalization of the state.

excerpt from the book: THE FOUCAULT EFFECT, STUDIES IN GOVERNMENTALITY/ LECTURES BY MICHEL FOUCAULT

loading...

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Steven Craig Hickman - The Intelligence of Capital: The Collapse of Politics in Contemporary Society

Steven Craig Hickman - Hyperstition: Technorevisionism – Influencing, Modifying and Updating Reality

Archives

April 2020

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed