|

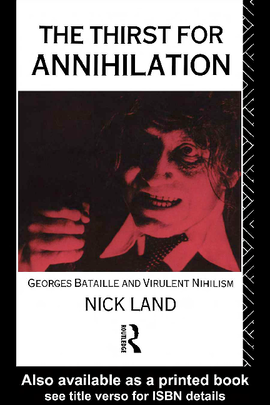

by Nick Land It is the green parts of the plants of the solid earth and the seas which endlessly operate the appropriation of an important part of the sun’s luminous energy. It is in this way that light—the sun—produces us, animates us, and engenders our excess. This excess, this animation are the effect of the light (we are basically nothing but an effect of the sun) [VII 10]. The solar ray that we are recovers in the end its nature and the sense of the sun: it is necessary that it gives itself, loses itself without reckoning [VII 10]. The peoples of ancient Mexico united man with the glory of the universe: the sun was the fruit of a sacrificial madness…[VII 192]. There is no philosophical story more famous than that narrated in the Seventh Book of Plato’s Republic, in which Socrates tells Glaucon of a peculiar dream. It begins in the depths of a ‘sort of subterranean cavern’ [PCD 747], in which fettered humans are buried from the sun, their heads constrained, to prevent them seeing anything but shadows cast upon a wall by a fire. The ascent through various levels of illusion to the naked light of the sun is the most powerful myth of the philosophical project, but it is also the account of a political struggle, in which Socrates anticipates his death. The denizens of the cave violently defend their own benightedness, to such an extent that Socrates asks: ‘if it were possible to lay hands on and to kill the man who tried to release them and lead them up, would they not kill him?’ [PCD 749]. Glaucon immediately concurs with this suggestion. Such violence is not unilateral. The philosopher, after all, has an interest in the sun that is not purely a matter of knowledge. To have witnessed the sun is a gain and an entitlement; a supra-terrestrial invitation (however reluctantly accepted) to rule: So our cities will be governed by us and you with waking minds, and not, as most cities now which are inhabited and ruled darkly as in a dream by men who fight one another for shadows and wrangle for office as if that were a great good, when the truth is that the city in which those who are to rule are least eager to hold office must needs be best administered and most free from dissension, and the state that gets the contrary type of ruler will be the opposite of this [PCD 752]. Light, desire, and politics are tangled together in this story; knotted in the darkness. For there is still something Promethean about Socrates; an attempt to extract power from the sun. (Bataille says: ‘The eagle is at one and the same time the animal of Zeus and that of Prometheus, which is to say that Prometheus is himself an eagle (Atheus-Prometheus), going to steal fire from heaven’ [II 40].) To gaze upon the sun directly, without the intervention of screens, reflections, or metaphors—‘to look upon the sun itself and see its true nature, not by reflections in water or phantasms of it in an alien setting, but in and by itself in its own place’ [PCD 748]— has been the European aspiration most relentlessly harmonized with the valorization of truth. Any aspiration or wish is the reconstruction of a desire (drive) at the level of representation, but the longing for unimpeded vision of the sun is something more; a ideological consolidation of representation as such. The sun is the pure illumination that would be simultaneous with truth, the perfect solidarity of knowing with the real, the identity of exteriority and its manifestation. To contemplate the sun would be the definitive confirmation of enlightenment. Gazing into the golden rage of the sun shreds vision into scraps of light and darkness. A white sun is congealed from patches of light, floating ephemerally at the edge of blindness. This is the illuminating sun, giving what we can keep, the sun whose outpourings are acquired by the body as nutrition, and by the eye as (assimilable) sensation. Plato’s sun is of this kind; a distilled sun, a sun which is the very essence of purity, the metaphor of beauty, truth, and goodness. Throughout the cold months, when nature seems to wither and retreat, one awaits the return of this sun in its full radiance. The bounty of the autumn seems to pay homage to it, as the ancients also did. Mixed with this nourishing radiance, as its very heart, is the other sun, the deeper one, dark and contagious, provoking a howl from Bataille: ‘the sun is black’ [III 75]. From this second sun—the sun of malediction—we receive not illumination but disease, for whatever it squanders on us we are fated to squander in turn. The sensations we drink from the black sun afflict us as ruinous passion, skewering our senses upon the drive to waste ourselves. If ‘in the final analysis the sun is the sole object of literary description’ [II 140] this is due less to its illuminative radiance than to its virulence, to the unassimilable ‘fact’ that ‘the sun is nothing but death’ [III 81]. How far from Socrates—and his hopes of gain—are Bataille’s words: ‘the sickness of being vomits a black sun of spittle’ [IV 15]. In order to succeed in describing the notion of the sun in the spirit of one who must necessarily emasculate it in consequence of the incapacity of the eyes, one must say that this sun has poetically the sense of mathematical serenity and the elevation of the spirit. In contrast if, despite everything, one fixes upon it with sufficient obstinacy, it supposes a certain madness and the notion changes its sense because, in the light, it is not production that appears, but refuse [le déchet], which is to say combustion, well enough expressed, psychologically, by the horror which is released from an incandescent arc-light [I 231]. Incandescence is not enlightening, but the indelicate philosophical instrument of ‘presence’ has atrophied our eyes to such an extent that the dense materiality of light scarcely impinges on our intelligence. Even Plato acknowledges that the impact of light is (at first) pain, because of ‘the dazzle and glitter of the light’ [PCD 748]. Phenomenology has systematically erased even this concession. Yet it is far from obvious why an absence/presence opposition should be thought the most appropriate grid for registering the impact of intense radiation. It is as if we were still ancient Hellenes, interpreting vision as an outward movement of perception, rather than as a subtilized retinal wounding, inflicted by exogenous energies. Everything begins for us with the sun, because (we shall come to see) even the cavern, the labyrinth, has been spawned by it. In a sense the origin is light, but this must be thought carefully. Our bodies have sucked upon the sun long before we open our eyes, just as our eyes are congealed droplets of the sun before copulating with its outpourings. The flow of dependency is quite ‘clear’ (lethal): ‘The afflux of solar energy at a critical point of its consequences is humanity’ [VII 14]. The eye is not an origin, but an expenditure. The first text in the Oeuvres Complètes is Bataille’s earliest published book: The Story of the Eye. It first appeared—under the pseudonym of Lord Auch—in 1928, which roughly places it amongst a group of early writings including The Solar Anus (1931), Rotten Sun (1930, quoted above), and the posthumously published The Pineal Eye (manuscripts dated variously 1927 and 1931). The common theme of these writings is the submission of vision to a solar trajectory that escapes it, dashing representational discourse upon a darkness that is inextricable from its own historical aspiration. The Story [Histoire] of the Eye is both the story and the history of the eye, as also The Pineal Eye is a fiction and a history. Every history is a story, which does not mean that the story escapes history, or is anything other than history consummating itself in a blindness which occupies the place of its proper representation. The Story of the Eye climaxes with the excision of a priest’s eye, which is ‘made to slip’ [glisser] into the vulva of the book’s ‘heroine’ Simone, once by her own hand, and once by that of Sir Edmond (an English roué). In this way the dark thirst which is the subterranean drive of the sun obliterates vision, drinking it down into the nocturnal labyrinth of the flesh. Similarly, in The Pineal Eye, the opening of ‘an eye especially for the sun’— appropriate to its ferocious apex at noon—invites an obliteration; blinding and shattering descent. The truth of the sun at the peak of its prodigal glory is the necessity of useless waste, where the celestial and the base conspire in the eclipse of rational moderation. By concluding the movement of ascent that is synonymous with humanity, and providing vision with the verticality that is its due, the pineal eye crowns the epoch of reason; opening directly onto the heavens (where it is instantaneously enucleated by the deluge of searing filth which is the sun’s truth): I represented the eye at the summit of the skull to myself as a horrible volcano in eruption, with exactly the murky and comic character which attaches to the rear and its excretions. But the eye is without doubt the symbol of the dazzling sun, and the one I imagined at the summit of my skull was necessarily inflamed, being dedicated to the contemplation of the sun at its maximum burst [éclat[II14]. The fecal eye of the sun is also torn from its volcanic entrails and the pain of a man who tears out his own eyes with his fingers is no more absurd than that anal setting of the sun [II 28]. The perfect identity between representation and its object—‘blind sun or blinding sun, it matters little’ [II 14]—is thought consistently in these early texts as the direct gaze; an Icarian collapse into the sun which consummates apprehension only by translating it into the register of the intolerable. In the copulation with the sun—which is no more a gratification than a representation—subject and object fuse at the level of their profound consistency, exhibiting (in blindness) that they were never what they were. The unconscious—like time—is oblivious to contradiction, as Freud argues. There is only the primary process (Bataille’s sun), except from the optic of the secondary process (representation) which—at the level of the primary process—is still the primary process. This is a logically unmanageable dazzling, quite useless from the perspective of reason, which seeks to differentiate action on the basis of reality. This libidinal consistency, which is (must be) alogically the same as the sun, is the thread of Ariadne, tangled in the labyrinth of impure difference. At the beginning of The Solar Anus Bataille notes that: Ever since phrases have circulated in brains absorbed in thought, a total identification has been produced, since each phrase connects one thing to another by means of copulas; and it would all be visibly connected if one could discover in a single glance the line, in all its entirety, left by Ariadne’s thread, leading thought through its own labyrinth [I 81]. All human endeavour is built upon the sun, in the same way that a dam is built upon a river, but that there could be a solar society in a stronger sense—a society whose gaze was fixed upon the death-core of the sun—seems at first to be an impossibility. Is it not the precise negation of sociality to respond to the ‘will for glory [that] exists in us which would that we live like suns, squandering our goods and our life’ [VII 193]? Without doubt any closed social system would obliterate itself if it migrated too far into the searing heart of its solar agitation, unpicking the primary repression of its foundation. It is nevertheless possible for a society to persist at the measure of the sun, on condition that a basic aggressivity displaces its sumptuary furore from itself, so that it washes against its neighbours as an incendiary rage. It is such a tendency that Bataille discovers in the civilization of the Aztecs, whose sacrificial order was perpetuated by means of military violence. In The Accursed Share—his great work of solar sociology—he remarks of the Aztecs that: The priests killed their victims upon the top of pyramids. They laid them on a stone altar and stabbed them in the chest with an obsidian knife. They tore out the heart—still beating—and lifted it up to the sun. Most of the victims were prisoners of war, justifying the idea that wars were necessary to the life of the sun: wars having the sense of consumption, not that of conquest, and the Mexicans thought that, if they ceased, the sun would cease to blaze [VII 55]. What unfolds beneath Bataille’s scrutiny cannot be an apology for the Aztecs or even an explanation. What is at stake in his reading of their culture is an economic intimacy, or thread of solar complicity, the pursuit of genealogical lineages that weave all societies onto the savage root-stock of the stars. The raw energy that stabbed the Aztecs into their ferocities is also that which—regulated by the apparatus of an accumulative culture— drives Bataille in his researches. The energetic trajectory that transects and gnaws his entrails is the molten terrain of a dark communion, binding him to everything that has ever convulsed upon the Earth. It is precisely the senseless horror of Aztec civilization that gives it a peculiar universality; expressing as it does the unavowable source of social impetus. ‘The sun itself was to their eyes the expression of sacrifice’ [VII 52], and their energies were dedicated to a carnage without purpose, whereby they realized the truth of the sun upon the earth. It seems to Western eyes as though their hunger for blood were indefensible, based upon ludicrous myths, and exemplifying at the extreme a human capacity to be perverted by untruth. If the culture of the Aztecs had been rooted in an arbitrary mythological vision such a reading might be sustained, but for Bataille the thirst for annihilation is the same as the sun. It is not a desire which man directs towards the sun, but the solar trajectory itself, the sun as the unconscious subject of terrestrial history. It is only because of this unsurpassable dominion of the sun that ‘[f]or the common and uncultivated consciousness the sun is the image of glory. The sun radiates: glory is represented as similarly luminous, and radiating’ [VII 189], such that ‘the analogy of a sacrificial death in the flames to the solar burst is the response of man to the splendour of the universe’ [VII 193], since ‘human sacrifice is the acute moment of a contest opposing to the real order and duration the movement of a violence without measure’ [VII 317]. Belonging alongside ‘sacrifice’ in Bataille’s work is the word ‘expenditure’, dépense. This word operates in a network of thought that he describes as general or solar economy: the economics of excess, outlined most fully in the same shaggy and beautiful ‘theoretical’ work—The Accursed Share—in which he writes: ‘the radiation of the sun is distinguished by its unilateral character: it loses itself without reckoning, without counterpart. Solar economy is founded upon this principle’ [VII 10]. It is because the sun squanders itself upon us without return that ‘The sum of energy produced is always superior to that which was necessary to its production’ [VII 9] since ‘we are ultimately nothing but an effect of the sun’ [VII 10]. Excess or surplus always precedes production, work, seriousness, exchange, and lack. Need is never given, it must be constructed out of luxuriance. The primordial task of life is not to produce or survive, but to consume the clogging floods of riches—of energy—pouring down upon it. He states this boldly in his magnificent line: ‘The world…is sick with wealth’ [VII 15]. Expenditure, or sacrificial consumption, is not an appeal, an exchange, or a negotiation, but an uninhibited wastage that returns energy to its solar trajectory, releasing it back into the movement of dissipation that the terrestrial system—culminating in restricted human economies— momentarily arrests. Voluptuary destruction is the only end of energy, a process of liquidation that can be suspended by the acumulative efforts whose zenith form is that of the capitalist bourgeoisie, but only for a while. For solar economy ‘[e]xcess is the incontestable point of departure’ [VII 12], and excess must, in the end, be spent. The momentary refusal to participate in the uninhibited flow of luxuriance is the negative of sovereignty; a servile differance, postponement of the end. The burning passage of energetic dissipation is restrained in the interest of something that is taken to transcend it; a future time, a depredatory class, a moral goal… Energy is put into the service of the future. ‘The end of the employment of a tool always has the same sense as the employment of the tool: a utility is assigned to it in its turn—and so on. The stick digs the earth in order to ensure the growth of a plant, the plant is cultivated to be eaten, it is eaten to maintain the life of the one who cultivated it…The absurdity of an infinite recursion alone justifies the equivalent absurdity of a true end, which does not serve anything’ [VII 298]. * One consequence of the Occidental obsession with transcendence, logicized negation, the purity of distinction, and with ‘truth’, is a physics that is forever pompously asserting that it is on the verge of completion. The contempt for reality manifested by such pronouncements is unfathomable. What kind of libidinal catastrophe must have occurred in order for a physicist to smile when he says that nature’s secrets are almost exhausted? If these comments were not such obvious examples of megalomaniac derangement, and thus themselves laughable, it would be impossible to imagine a more gruesome vision than that of the cosmos stretched out beneath the impertinently probing fingers of grinning apes. Yet if one looks for superficiality with sufficient brutal passion, when one is prepared to pay enough to systematically isolate it, it is scarcely surprising that one will find a little. This is certainly an achievement of sorts; one has found a region of stupidity, one has manipulated it, but this is all. Unfortunately, the delicacy to acknowledge this— as Newton so eloquently did when he famously compared science to beach-combing on the shore of an immeasurable ocean (= 0)—requires a certain minimum of taste, of noblesse. Physicalistic science is a highly concrete, sophisticated, and relatively utile philosophy of inertia. Its domain extends to everything obedient to God (he is dead, yet the clay still trembles). Within this domain lie many tracts that have momentarily escaped cultivation; ‘facts of spirit’ for example, along with constellations of docility of all kinds, but these are not sites of resistance. Science is queen wherever there is legitimacy; perhaps terra firma as a whole belongs to her. No one would hastily dispute her rights, but the ocean is insurrection (and the land—it is whispered—floats). Even after the infantile hyperbole of the scientific completion myth has been set aside, there is still a question concerning the success of science that remains untouched. It cannot be seriously doubted that philosophy has been damaged by science, for it has even come to anticipate its extinction. It has now reached the stage where it has lost all confidence in its power to know, where envy has totally replaced parental pride, and where the stylistic consequences of its bad conscience have devastated its discourse to the point of illegibility. For at least a century, and perhaps for two, the major effort of the philosophers has simply been to keep the scientists out. How much defensiveness, pathetic mimicry, crude self-deception, crypto-theological obscurantism, and intellectual poverty is marked by the name of their recent and morbid offspring die Geisteswissenschaften. The first and most basic source of this generalized neurosis amongst the practitioners and dependents of philosophy is their incomprehension of quite how it was that ‘they’ gave birth to the sciences. They tend to think that they were always bad scientists, or at least, immature ones. ‘If only we had been better at maths’ they mutter under their breath, as they take a mournfully nostalgic pleasure in the fact that as calculators Newton and Leibniz still seemed to be ‘neck and neck’. What is lost to such melancholy is the fact that philosophy does not relate to science as a prototype, but as a motor. It was the basic source of investigative libido before being supplanted by the arms industry, and if science has not yet been completely dissolved into a process of technical manufacture, the difference is only a flux of inexplict philosophy. For philosophy is a machine which transforms the prospect of thought into excitation; a generator. ‘Why is this so hard to see?’ one foolishly asks. The answer quickly dawns: the scholars. Scholarship is the subordination of culture to the metrics of work. It tends inexorably to predictable forms of quantitative inflation; those that stem directly from an investment in relatively abstracted productivity. Scholars have an inordinate respect for long books, and have a terrible rancune against those that attempt to cheat on them. They cannot bear to imagine that short-cuts are possible, that specialism is not an inevitability, that learning need not be stoically endured. They cannot bear writers allegro, and when they read such texts—and even pretend to revere them—the result is (this is not a description without generosity) ‘unappetizing’. Scholars do not write to be read, but to be measured. They want it to be known that they have worked hard. Thus far has the ethic of industry come. Curiosity has imperilled itself in its questioning, it has even harmed itself. That it has not traversed its history triumphantly is only one of the many certainties that it suffers from. It is all too obvious that the Russian roulette of the interrogative mode has led to its near extinction; maimed in the brain by the rigorous slug of the natural sciences. For the responses it has provoked have usually lacked even the bitter solace of aporia. To some the world is beginning to seem a crudely intelligible place; a desert of simplicity, dotted with the stripped bones of inquisitiveness. What if curiosity was worth more than comprehension? This is not such an impossible thought to entertain. Nor is it unreasonable to ask after the necessity that has led the motor of thought to be subordinated to its consequences. Resolution could only be desirable if there existed an interest superseding thought. Otherwise it should be merely a means, the end of which is the promotion of enigma and confusion. That thought has to tolerate solutions is simply an unfortunate necessity. Perhaps not even that. Curiosity is a desire; a dynamic impulse abolished by petrification. It would be an idiocy—although an all too familiar one—to try to preserve it in the formaldehyde of obscurantism and mystique. For an eternal mystery is as devastating to curiosity as any certainty could be. The ideology of thought’s exterminators is dogmatism, it scarcely matters of which kind. It is not the ability to preserve riddles that has value, but the ability to engender them. Any text that persists as an acquisition after coming to a comfortable end has the character of a leech, nourishing itself on the blood of problematic, and returning only repulsive inertia. The fertility of a text, on the contrary, is its inachievement, its premature termination, its inconclusiveness. Such a text is always too brief, and instead of a draining anaesthetic attachment there is the sting. This book is not of that kind, it slows Bataille down, driving his fleet madness into a swamp of metaphysics and pseudo-science. My refusal to surrender the sun to the denizens of observatories—and the unseemly tussle that results—makes my relation to Bataille somewhat problematic, wrecking large tracts of my text. My relation to scientific knowledge, on the other hand, is nothing less than a scandal. What I offer is a web of half-choked ravings that vaunts its incompetence, exploiting the meticulous conceptual fabrications of positive knowledge as a resource for delirium, appealing only to the indolent, the maladapted, and the psychologically diseased. I would like to think that if due to some collective spiritual seism the natural sciences were to become strictly unintelligible to us, and were read instead as a poetics of the sacred, the consequence would resonate with the text that follows. At least disorder grows. by the book: The Thirst for Annihilation/Chapter 2: The Curse of the Sun by Nick Land

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Steven Craig Hickman - The Intelligence of Capital: The Collapse of Politics in Contemporary Society

Steven Craig Hickman - Hyperstition: Technorevisionism – Influencing, Modifying and Updating Reality

Archives

April 2020

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed