|

by Edmund Berger

The story goes like this: Earth is captured by a technocapital singularity as renaissance rationalitization and oceanic navigation lock into commoditization take-off. Logistically accelerating techno-economic interactivity crumbles social order in auto-sophisticating machine runaway. As markets learn to manufacture intelligence, politics modernizes, upgrades paranoia, and tries to get a grip. 1

loading...

These are the opening lines of “Meltdown,” a short, hallucinatory psalm, spoken on behalf of the capitalism of the information age and, more specifically, the schizoid bifurcation points occurring in the cracks and fissures it triggers across the globe. Initially impenetrable yet strangely alluring, the text’s language is poetic in form, its progenitors found in critical theory and cyberpunk fiction and film, and its logic machinic and amphetamine addled. The place is the University of Warwick in the early 90s, and the author is a former Continental Philosophy lecturer by the name of Nick Land. “Meltdown: planetary china-syndrome, dissolution of the biosphere into the technosphere, terminal speculative bubble crisis, ultravirus, and revolution stripped of all christian-socialist eschatology.”

A little background information: “Meltdown” is torn from the pages of Abstract Culture, the journal/decentralized cultural mirror put out by the now-defunct Cybernetic Cultures Research Unit (CCRU). With its brief nexus located at Britain’s Warwick University, CCRU was the brainchild of cyber-feminist Sadie Plant and Land himself, with a supporting cast of characters who have gone on to radicalize social and academic spaces in various ways: Steve Goodman, an early innovator of dubstep, well known under his moniker Kode9; Mark Fisher, the force behind the K-Punk blog and author of Capitalist Realism; Kodwo Eshun, whose work More Brilliant than the Sun employs “sonic fiction” to explore the musical trajectories of afro-futurism; Iain Hamilton Grant, a philosopher and translator of texts by Jean Baudrillard and Jean-Francois Lyotard; among others. Running through the thoughts manifested by these individuals is the emergent philosophical lineage called ‘speculative realism,’ eschewing post-Kantianism’s correlationism in exchange for a quasi-nihilist metaphysical realism abound with nods to Lovecraft and modern cultural trends. Its impossible to speak of CCRU and the frantic cybertheories they repeatedly injected into dry academic ivory towerism without providing a cursory mention to Sadie Plant. A graduate of the University of Manchester’s philosophy program, Plant’s Ph.D thesis-turned book The Most Radical Gesture: The Situationist International in a Postmodern Age gained her renown and a position as a researcher fellow at the University of Warwick’s Social Sciences department. Her curious brand of post-Situationist/post-Thatcher cyber-feminism initially seemed to fit the bill for Warwick’s intellectual climate, drenched in information technology research and the hybrid political philosophies of Gilles Deleuze and Felix Guattari. To assist her work, CCRU was set up in 1995 as a sort of adjunct facility – but when joined by Nick Land, it quickly transformed itself into what has been described as a sort of university equivalent to Colonel Kurtz and his frightening, psychedelic war machine from the end of Apocalypse Now. Land’s animosity towards the academic universe’s unwritten commandments and careerist bureaucracy had already been readily apparent in his 1992 work The Thirst for Annihilation: Georges Bataille and Virulent Nihilism, a “deranged mix of prose-poem, spiritual autobiography and rigorous explication of the implications of Bataille’s thought.”2 He quickly overtook Plant’s position as steward of the unit, spinning it into a thousand directions, simultaneously encompassing philosophy, physics, biology, mysticism, and all manner of beyonds, sidestepping through the disciplines and exploring the strange spaces between them in a sort of D.I.Y. remix of Norbert Weiner’s original research into cybernetics.

CCRU received ample boosts from sweaty dance floors moved by the sample-heavy bass and backbeats of jungle, dropping chopped-up and scrambled variants of previous musical cultures into the blossoming rave scene of the UK. Jungle’s method of appropriating micro-units of traditional sonic form and social detritus by the way of Kingston’s dub sound systems and Britain’s own recent punk/post-punk past provided a close analogue, in the eyes of the Warwick’s renegade explorers, to the overdriven systematics of post-Fordist capitalism; its tendency towards crisis were also collapsing into Bataille’s feverish fixation on existence in the face of the apocalypse. Capitalism and jungle collide through Abstract Culture with pop culture nuggets reflecting the technological innovations in military hardware, the internet, and other communication platforms: film such as Blade Runner and Terminator, cyberpunk fiction like William Gibson’s Neuromancer, each capturing visions of the future where technology has reached escape velocity, exiting the terrestrial plane with a humanity dragged along with it. Limits dissolving not simply into thresholds, but innumerable exit points.

And thus Land and the CCRU, now minus Plant, produced a bizarre and complex theoretical position called “accelerationism.” Academia was stagnant, reflecting a wider stagnation in the government and the social. State-thought pervaded every level, stifling creativity and movement, reducing everything to the drab and gray monoliths of housing projects – repetition. Everywhere was overwritten with codes, essentially dictating what one can think and what one could do. Even the so-called opposition was complicit. The Old Left was incapable of transforming itself with the changing times, getting themselves lodged in the muck of the laborist paradigm of big unionism and legislative quagmires. With the dawn of complex information technologies and its proliferation on the grassroots level, combined with the perceived assault on stateform through the neoliberal program, CCRU produced a radically new proposition for revolutionary change that differed wildly from the Marxist-lite meanderings of the professional left. Emancipation from traditional and constraining modes of thought could come, they argued, from the apparatuses of capitalism itself. Monetary flows had the capability, as Marx himself had observed, to make everything solid “melt into air.” Solidity was stagnation; accelerating the melting process thus became essential. Looking at it like this, Marx can been seen as a proto-accelerationist, counting on capitalism to cultivate the proper moment where the “revolution” – whatever that truly means – would flash into existence. But Marx’s method was based in dialectical materialism, a reworking of what is otherwise a philosophical position fixed in a linear and totalizing cosmology. Land and the CCRU, on the other hand, resisted the Hegelian discourse that was the trademark of the dominant state-thought. Instead, they relied heavily on post-Marxist, anti-Hegelian theory emerging in France following the collapse of May ’68’s utopian aspiration – namely, the work of Deleuze and Guattari and those who followed in their footsteps. The Accelerationist Moment

So now it is high time to speak of the disembodiment of reality, this sort of breakdown which, one should think is applied to a self-multiplication proliferating among things and the perception of them in our minds, which is where they do belong – Antonin Artaud, “Description of a physical state”3

Several key texts from the 1970s have been identified as the locus of the accelerationist theory: Deleuze and Guattari’s Anti-Oedipus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia (1972), Lyotard’s Libidinal Economy (1974), Baudrillard’s Symbolic Exchange and Death (1976), and, I would argue, his infamous Forget Foucault (1977), with an aftershock of sorts occurring in Michael Hardt and Antonio Negri’s Empire (2000). All these works share a commonality in new understandings of capitalism, socialism, control, and resistance; they map new and expectant cartographies of the then-present and the now-current future. Furthermore, each zeroes in the nature of the new paradigm where the logic of revolt that fueled the events of 1968 have become the twin logics of production and consumption, the new language of the marketplace.

Deleuze and Guattari’s Anti-Oedipus oscillates somewhere between fiction and reality, between radical critique and poetic manifesto – utilizing an assault on Freudianism and Hegelian dialectic with an arsenal of weapons stripped from Marx, Spinoza and Nietzsche, they propose a new model of the unconscious mind. No longer is it a theater of symbols, as Freud posited, but a factory where flows of machines of desire couple and disconnect from one another. Their model of the machinic unconsciousness collapses the superficial boundaries between man and nature, mind and body, and all other manner of dialectics. Current social structures, on the other hand, impose boundaries and block flows, reroute them, capture them for their own rationale, and overcode them. Deleuze and Guattari further their strange new world by producing the concept of ‘nomad thought’ – a formulation with its roots in the Situationist derive or drift, a manner of looking for divergent modes of becoming that finds passages to the outside of the logic and ‘rationalized’ discipline that power creates. This nomadic mechanism is complimented with a charting of the convergences between capitalism and the desiring flows, showing how the system’s tendency towards dissolution breaks down the traditional codework. This isn’t to say that capitalism as-is is the fiscal equivalent of nomadic thought, but there are similarities, the most principle being the concept of deterritorialization. Probing these approaches, Deleuze and Guattari ask:

…which is the revolutionary path? Is there one? – To withdraw from the world market,as Samir Amin advises Third World countries to do, in a curious revival of the fascist “economic solution”? Or might it be to go in the opposite direction? To go further still, that is, in the movement of the market, of decoding and deterritorialization? For perhaps the flows are not deterritorialized enough, not decoded enough, from the viewpoint of a theory and a practice of a highly schizophrenic character. Not withdraw from the process, but to go further, to “accelerate the process,” as Nietzsche put it: in this matter, the truth is that we haven’t seen anything yet.4

loading...

Even if this is the only place in book where the theory of accelerationism is expressed directly, the entire work illustrates the need for a revolution built upon moving into a beyond through the folds of deterritorialization. They call for a “schizoanalysis,” a radical new form of psychotherapy built upon the model of the schizophrenic – as opposed to the Freudian school’s emphasis on neurosis – to allow for brushes with alterity (otherness) to trigger accelerated processes of becoming. Schizoanalysis, nomadic thought, the flows, there is little separating these, and each urges us to go further and further, beyond doctrinaire Marxism and even the text of Anti-Oedipus itself.

Within four years, Jean-Francois Lyotard, a veteran of May ’68 and a close friend of Deleuze, had taken up their challenge, effectively schizoanalyzing Anti-Oedipus into a strange new formation that he dubbed Libidinal Economy. He would later disown the book, calling it “evil;” while this is certainly hyperbolic, the ideas expressed within isolated him from mainstream Marxist currents. Rejecting the left’s vanguardist approach to what they characterize as ‘proletarian consciousness,’ Lyotard conflates capitalism’s engine with the worker’s desire for deterritorialization and decoding. “Hang on tight and spit on me,” he commands, thrusting forward the insistence that the working class “enjoyed the hysterical, masochistic, whatever exhaustion it was of hanging on in the mines, in the foundries, in the factories, in hell, they enjoyed it, enjoyed the mad destruction of their organic body which was indeed imposed upon them, they enjoyed the decomposition of their personal identity…”5 Further still, the intelligentsia, by looking to direct the worker’s desires, was acting in a rather counter-revolutionary model and was complicit with the bourgeoisie: Why political intellectuals, do you incline towards the proletariat? In commiseration for what? I realize that a proletarian would hate you, you have no hatred because you are bourgeois, privileged, smooth-skinned types, but also because you dare not say that the only important thing there is to say, that one can enjoy swallowing the shit of capital, its materials, its metal bars, its polystyrene, its books, its sausage pâtés, swallowing tonnes of it till you burst – and because instead of saying this, which is also what happens in the desires of those who work with their hands, arses and heads, ah, you become a leader of men, what a leader of pimps, you lean forward and divulge: ah, but that’s alienation, it isn’t pretty, hang on, we’ll save you from it, we will work to liberate you from this wicked affection for servitude, we will give you dignity. And in this way you situate yourselves on the most despicable side, the moralistic side where you desire that our capitalized’s desire be totally ignored, brought to a standstill, you are like priests with sinners…6 After quickly as it had begun, Lyotard immediately retreated from his vitriolic theory-fiction and from a Deleuzian perspective in general, later penning his seminal work The Postmodern Condition: A Report on Knowledge in 1979. But nomadic wanderings were continued by Jean Baudrillard, whose philosophical trail had begun in the Situationist ferment but were becoming increasingly difficult and abstract. If Deleuze and Guattari had captured the late Sixties zeitgeist and Lyotard had taken these energies to produce a proto-punk refusal, Baudrillard’s Symbolic Exchange and Death and Forget Foucault was the first blast of cyberpunk – “it didn’t look like anything else that was being published in France during that period. It didn’t seem to belong there, or anywhere for that matter. It was as if it had fallen from outer space.”7 Symbolic Exchange assaults Deleuze, Guattari, and Lyotard, arguing that their work with ‘desire’ bound them into the dialectical system they were critiquing, and that the schizophrenic flows that desire moved in acted as justification for capitalism itself, which was then transitioning from the post-war Keynesian structure into free-floating, transnational neoliberalism. In other words, he could see fully the spectre of accelerationism and what it meant for any revolutionary alternatives. But, as Benjamin Noy points out, “The difficulty is that Baudrillard’s own catastrophising comprises a kind of negative acceleration, in which he seeks out the point of immanent reversal that inhabits and destabilizes capital.”8 With the aid of anthropology and Bataille’s work, he created the concept of “symbolic exchange,” dissolving the traditional value assigned in the marketplace of capitalist exchanges. This, he says, constitutes a “death function” for the system – but it can only occur if we challenge capitalism to embrace what it is, a monstrous and surreal complex, “endlessly cutting the branch on which it sits.”9 If Baudrillard directly foreshadowed the non-leftist accelerationism and fixation on Bataillian apocalypses of Nick Land, Hardt and Negri’s Empire attempted to re-situate Deleuze and Guattari’s original idea into a [post-]Marxist format in search of a liberatory politics. In 1972, the year that Anti-Oedipus had been published, President Nixon had removed the US dollar from the gold standard, effectively stripping capitalism from any material base and transforming it into a language game, a semiotic system of control that could circle the globe unfixed from the structures that had always augmented monetary flows. It was financial deterritorialization coming to fruition, and, to quote Baudrillard, power had “dissolved purely and simply in a manner that still escapes us.” This power, dispersed in transnational networks across the globe, would be given the name “Empire” by Hardt and Negri, and for them (like Baudrillard), there was no longer any alterity; modernism became postmodernism, Fordism dissolved in the face of post-Fordism, all the previous categories collapsing into one another. Because of this, reactionary revolt as a passage out will never lead to emancipation. We have to go forward: We cannot move back to any previous social form, nor move forward in isolation. Rather, we must push through Empire to come out the other side…Empire can be effectively contested only on its own level of generality and by pushing the process that it offers past their present limitations. We have to accept that challenge and learn to think globally and act globally. Globalization must be met with a counter-globalization, Empire with a counter-Empire.9 Flaws

In 1980, Deleuze and Guattari released their follow-up to Anti-Oedipus, an exercise in schizoanalytic nomadic thought they titled A Thousand Plateaus. Here, they seemed hesitant to their earlier vision of unabashed acceleration, offering instead words of caution. They were necessary words: Anti-Oedipus had been written while the revolutionary high of 1968 still hung in the air; but a decade later, left-wing terrorism, rampant drug abuse and rising neoliberalism had generate an aura of pessimism and in certain places, outright despair. They speak of ‘black holes,’ fascistic traps that deterritorializing flows can accelerate themselves into. To make revolution, to engage in processes of becoming, to escape along a line of flight, each operates as a bifurcation point that can lead outward, but there exists the dangers of ‘coiling’ inwards, toward structure and binary oppositions, dialectic stateform dependency – and, in the most extreme cases, death.

Nick Land saw this retreat, perceived as a sudden moralizing stance, as being antithetical to the ethos of Anti-Oedipus and something in the direction of a betrayal of the work’s spirit. His vision was one of capitalism as the harbinger of the end; he had dialed back a portion of their oeuvre and conjoined the schizoid flows to the Freudian death drive, or thanatos. If bourgeois humanism forms a reactionary mechanic of power, then only the antihumanism provided by the acceleration of capital and its technological counterparts could finally dissolve what is. In “Meltdown,” we find that “Man is something for it to overcome: a problem, drag.”10 Apocalyptic intensities aside, Land has conveniently sidestepped a critical aspect of Anti-Oedipus‘s analysis of capitalist deterritorialization. If deterritorialization advances the subversive forces in capitalism’s own flows, there is always the accompanying process of reterritorialization, which draws these unravels energies into a manageable system. These reterritorializations do not happen to spite capitalism, they happened in accordance with it, to stave off the death function that Baudrillard had found:

Capitalism institutes or restores all sorts of residual and artificial, imaginary, or symbolic territories, thereby attempting, the best it can, to recode, to rechannel persons who have been defined in the terms of abstract quantities. Everything returns or recurs: States, nations, families. That is what makes the ideology of capitalism “a motley painting of everything that has ever been believed.”11

We’re told in A Thousand Plateaus that “the nomad can be called the Deterritorialized par excellence… because there are no reterritorialization afterwards…”12 Thus, we can no longer draw as tidy parallels between nomadic becomings and capitalism as we have to this point, for the true threshold of the nomad is held off, existing only perhaps as a carrot to move power networks to resemble more and more the aesthetic and moral stances of their opposition. As neoliberal capitalism itself became deterritorialized following the end of the Fordist class compact, it simultaneously exalted itself as the great bestower of health,wealth and equality (just think of development programs for the Third World and the philanthropy of industrial and financial giants) while in reality acting as a great destroyer (cyclical crisis, mass wealth inequality, war). To confuse matters more, Deleuze and Guattari point their finger to the stateform itself, the system that was supposed to dissolve away under both Marxist-derived programs and neoliberalism, as the principle actor in the reterritorializations. As we can now see, looking backwards from the vantage point of the latest crises, the state never, ever went away in the neoliberal revolution; it only slightly altered its function, retracing itself in the image of the market. It still creates level after level of bureaucracy, bails-out, enforces laws, regulates, and manages the direction that so-called free trade moves in.

Land once remarked in an interview that “organization is suppression,” a phrase so anarchic that it could have been found just as easily in the graffiti of the Situationists in 1968 or in the manifestos of the Italian Autonomists in the late 1970s. Following this logic, we can reach the conclusion that the acceleration of capitalism proper will never bestow a post-suppression environment, by virtue of the existence of the corporate model alone. With the modern corporation, the center of power and politics in the neoliberal sphere, we have a multilevel institution operating with the sanction of the state – through the granting of corporate charters – and, frequently, receives direct financial lines from the public coffers in the form of subsidies. And while the corporation is the principle arbiter of capitalism’s global flows, encompassing the monetary, the material, and human elements, it acts as a lopsided entity, a mass centralization that works not with the market, but against it. Manuel deLanda, drawing on research of Fernand Braudel, assigns both the corporation and the idea of capitalism itself to the category of the anti-market – the systems of “large scale enterprises, with several layers of managerial strata, in which prices are set not taken.”13 In contrast to the anti-market is the marketplace proper, a complex “meshwork” of both exchange and production, operating in primarily localized settings and through decentralization – small firms and individuals that actually determine price and labor conditions. deLanda’s meshworks were reflected in the CCRU’s interest in the bottom-up “street markets… a bustling bazaar culture of trade and ‘cutting deals’”,14 and also brings to mind Deleuze and Guattari’s articulation of the ‘rhizome’, a decentralized network formation that spreads across smooth spaces, free from hierarchy and command. Yet deLanda warns not to look to the meshwork of the market as something completely revolutionary; while they can resist them, they can also reinforce traditional binaries and hierarchies. There is also the issue of growth, which places the meshworks on a natural trajectory that can lead them to become anti-markets. The rhizome model is to be contrasted with that of a tree, but the figurative tree, not the process of further deterritorialization, is what can grow from the marketplace.

If we are speaking of illusionary rhizomes and false promises of open networks, we can turn to the other side of the accelerationist coin: the advancing marches of technology revolving around the internet itself. An interactive medium encompassing text and image, code and emotion, history and the future, global interrelation, the internet’s highly schizophrenic and every-shifting nature, its perpetual self-connection through hyperlinks, makes itself appear to be the fulfillment of the rhizome: “Principles of connection and heterogeneity: any point of rhizome can be connected to any other, and must be…A rhizome ceaselessly establishes connections between semiotic chains, organizations of power, and circumstances relative to the arts, sciences, and social struggles.”15

But the internet has its trees and has always had its trees, unlike even the the deLandian market, which becomes hierarchical and treelike. From the beginning it was an agenda of Cold War politics, born from the research laboratories of DARPA and its allied universities. When it came time for the great privatization, it was handed off to corporate monopolies, anti-markets in the purest sense of the word, free from any real competition or external threats. The telecommunication giants serve as the internet’s gatekeepers, the guardians of the flows of information; digital ‘freedom’ comes at the cost of a monthly subscription and the consent to be monitored. And for many, the freedom doesn’t even exist – there is currently a growing crisis, particularly in the US, where people living in rural areas are deprived of internet access. This unfortunate problem stems from the service providers themselves, who simply choose not to operate in these regions because lower population densities would mean lower revenue streams. A double centralization occurs: a digital one, in the form of the ISP’s role as a gatekeeper, and a geographical one, where power, knowledge, and opportunities remain situated in the urban zones. To even begin to truly decentralized the world wide web and flatten out its intrinsic hierarchies, its not a matter of acceleration. Its a matter of a total structural change, a new paradigm for digital futures entirely. Despite this, however, the spaces of the internet play host to a whole series of deterritorializations. Cyber warmachines – Anonymous, WikiLeaks, the countless advocates of open source technology, social media users in times of political struggle– are capable of crossing the digital threshold and impacting the physical world in very real ways, changing the contours of everyday life. File sharing platforms such as music blogs, torrent sites, and smaller, individualized programs allow capitalist creative destruction to impede on the constructs of copyright and intellectual property, while deeper structures, the darknet and TOR networks, allow for subterfuge and anonymity from the prying eye of government agencies and corporate data collectors.

We can extoll the virtues of these deterritorializations, for they constitute very real examples of radical becomings with the tools we have available. Yet the spectre of reterritorialization haunts them still, with the state taking on the very roles identified in Anti-Oedipus. As copyright laws become dismantled with the digitalization of music, film, text and information, governments have stepped in to take an active role in taking down hosting sites – an development situated in a great agenda of internet regulation and creation of watchdog agencies. Very real political repression of WikiLeaks is occurring, while the continual use of the TOR networks, stereotyped as a digital ‘wild west’, by violent and exploitative criminal elements only amplifies the calls for intervention. The digital sphere has reached a point where it serves as a mirror of the great neoliberal system, a state of affairs that was predicted decades ago by cyberpunk authors. In works such as Neuromancer, lauded by Land and the CCRU, technology is inseparable from the human body and his external environment while corporate monoliths act in the void left by the absence of functional government – but there exists a strange contradiction in that individuals living and acting on the level of the physical and digital streets have assumed heightened degree of autonomy while also being subjected to the greater ebbs and flows of power. In the cyberworld, as well as the real world, sources for freedom and the bindings of control are being transmitted from the same source – the schizoid movement of capital itself. Through this paradigm, perhaps we can push acceleration away from its looming black holes and reconnect it, as Hardt and Negri try to do, to some form of revolutionary politics.

“The street finds its own use for things” I now sense an extraordinary acceleration in the decomposition of all coordinates. Its a treat just the same. All this has to crumble down, but it won’t come from any revolutionary organization. Otherwise you fall back on the most mechanistic utopias of the revolution utopias, the Marxist simplifications… The Italians of Radio Alice have a beautiful saying: when they are asked what has to be built, they answer that the forces capable of destroying this society surely are capable of building something else, yet that will happen on the way. – Felix Guattari, “Why Italy?”16

At this juncture I would like to interject a new text into the accelerationist canon: The Uprising: On Poetry and Finance, recently written by Italian autonomist icon Franco “Bifo” Berardi (who, incidentally, was the founder of the Radio Alice mentioned in the quote above). Its concern certainly isn’t accelerationism per se, but a snapshot of the crisis of largely deterritorialized neoliberalism, taken at the feverpitch of the US Occupy movements, the renewed left-wing insurgency in Europe, and the Arab Spring. As the new democratic consciousness (if it can be called that) swept up malaise and despair and transmorphed them into anti-capitalist meshworks, Bifo reminds us of the crisis of technocapitalism had very real and dangerous possibilities for reterritorializations, harking back to Deleuze and Guattari’s black holes. The text draws forth apocalyptic imagery: the punk refrain of “no future”, violence, the specter of fascism. In many ways, it resembles (in tone, certainly not wording) Land’s own accelerated apocalypse – government’s corruption by “narco-capital” and the transfer of its police and military powers to “borderline-Nazi private security organizations”, the “urban warscape” and the “feral youth cultures” crawling their way through the “derelicted warrens at the heart of darkness.”17

All these things have come to pass, with the war on drugs transforming Mexico into a failed state, the privatization of warfare and relief with Blackwater in Iraq and New Orleans, the rise of the Golden Dawn in Greece… From here, Land appears not as our Nietzsche, as Fisher claims, but our Antonin Artaud, embodying the crisis in his precognitive, end times-tinged madness, while simultaneously showing potential avenues for exodus, passages to the outside. To quote his former student and fellow CCRUer, Robin MacKay, “academics talked endlessly about the outside, but no-one went there. Land, by exemplary contrast, made experiments in the unknown unavoidable…” 18 Anti-Oedipus, by way of MacKay and Fisher: “A breath of fresh air, a little relation to the outside, that’s all schizoanalysis asks.”19 Where is this outside, the big other, alterity? As we’ve mentioned, in post-Fordist neoliberalism, its vanished, existing only as prepackaged exoticism. This provides a fundamental paradox – Hardt and Negri, in their own formula of acceleration, repeatedly tell us that Empire must be pushed to the “other side” (where is this other side?) and that exodus from the system constitutes a vital strategy (exodus to where?). Exodus can no longer inhabit a physical outside, so the only place that exodus can occur is within – both in the social spaces of capitalism itself and in the individual itself. Again, nomadic thought, the traversing even the exteriority inside oneself. But we cannot escape into pure thought, float like the original surrealists amongst the unconscious pools of phantasms and dreams – or can we? Shed of its Freudian and Stalinist ambitions, surrealism can show how drifting through the mind’s ambiances can create form in the physical world. “Art cannot change the world, but it can contribute to changing the consciousness and drives of the men and women who could change the world.”20 Let us conjoin these notions with George Jackson, by way of Anti-Oedipus: “I may take flight, but all the while I am fleeing, I will be looking for a weapon.”21 We can now loop this back to one of starting points, Deleuze and Guattari’s recomposition of the unconscious mind as a flowing factory of desiring-machines. Desire is not necessarily libidinal, as Freud and his alcolytes would have it; at its basis, it is a creative force. If capitalism has seized desire into its own deterritorializing and reterritorializing processes, then a proper method of acceleration would not have to be capitalism itself, but of the rhizomatic creativity buried within it. How else can we dodge the hierarchies of command and centralization that follow in the stateforms wake? Land’s acceleration, in the speculative sense and the market sense, concerns itself, at its core, with one thing: pushing past its limits. Here Bifo is central: he notes that in the 90s, capitalism did accelerate, straight into what was predicted by CCRU – a collapse with shades of the apocalypse. And in a similar train of thought, he expounds a thesis that traditional forms of solidarity, and forms of resistance, are an impossibility, assigned to the dustbins of nostalgia that keep the system’s heart beating even when it has, for all intents and purposes, died on the operating table. Instead, he turns to a different form of limit-busting, that of language itself, the experience of which “happens in finite conditions of history and and existence… Grammar is the establishment of limits defining a space of communication.”22 Capitalism, at the end of history, descended into the empty circulation of linguistic signs and symbols, abstracts. Now we can scramble these linguistic parameters further, seize them and appropriate them, use them to eek out new conditions for solidarity. The mechanism he proposes is poetry, “the reopening of the indefinite, the ironic act of exceeding the established meaning of words.” I think back to Magritte and his most famous work of surrealism, the juxtaposition of the image of a pipe with the words ‘this is not a pipe’ – code scrambling need not be poetry alone, but any aesthetic form.

If this linguistic-aesthetic turn seems too abstract, consider that speech itself forms part of the rock on which subjectivity is built: “I is an other, a multiplicity of others, embodied at the intersection of partial components of enunciation, breaching on all sides individuated identity and the organized body.”23 Guattari divides up the impact of these forms of enunciation, placing on oneside the signifying system of “emtpy speech”, direct command and logistical control; and on the other, “ordinary speech,” an complex affective system that encompasses not only the words themselves but articulates itself in conjunction with tonations, rhythms, facial expression, collaboration. Take the academic ivory tower, railed against by Land – theory-talk, political correctness, servitude to the given field’s magistrates and the cookie-cutter essay format, all provide a one-way uniformity in the student body, who pass on these hierarchies and overcodes in their own careers. Empty speech and all that it entails acts as a self-replicating system of control, and what is at stake is an autonomy of subjectivity itself.

Lets look at another example of subjectivity with connections to the CCRU moment: rave culture, the emergence of which Sadie Plant linked to the collapse of Britain’s labor paradigm under Thatcher’s neoliberal revolution as a method for finding new forms of collectivity. Curiously, it resembled deLanda’s meshworks: it initially flourished in the underground, linked by cottage industries and word of mouth, secret codes and maps pointing the way to parties. The patchwork music, cobbled from various sources and blended into an alchemical mixture, established the smooth sonic space where the rave took place, but the DJ or MC, in collaboration with the ravers, utilized polyphonic enunciations (oohs and ahhs, toasting, complex affective exchanges) to create emergent subjectivities that were far more collective than individual, subjectivities that looked for the outside at a time when none could be found or occur:

In her memoir Nobody Nowhere, the autistic Donna Williams describes how as a child she would withdraw from a threatening reality into a private preverbal dream-space of ultravivid color and rhythmic pulsations; she could be transfixed for hours by iridescent motes in the air that only she could perceive. With its dazzling psychotropic lights, its sonic pulses, rave culture is arguably a form of collective autism. The rave is utopia in its original etmymological sense: a nowhere/nowhen wonderland.24 (emphasis in original) Quite literally a deterritorialization in the truest sense of the word – and one following the trajectory of capital acceleration – rave culture was quickly reterritorialized for capitalism by the state: crackdown on illegal parties, the creation of new laws, the centralization of power in the hands of corporate promoters, attacks on MDMA, all these moved rave culture away from the ‘margins’ and into the mainstream. A line of flight consisting of enunciation, aesthetics and movement, it ended up rebolstering the consumptive process of the spectacle, but there are still divergent deterritorializations utilizing the initial ethos against the powers of transnational capitalism. I’m talking here of the alter-globalization movement’s “Reclaim the Streets” (RTS) program of direct action. Rave party and protest collide together in streets of urban space, the arteries of the centers of postmodern capitalism. By occupying the streets and turning them into public bazaars, social centers and dance parties, a new form of social collectivity is produced: the Common, not only in the sense of a space of mutual aid and collective work, but also as a form of multifaceted enunciation. The fact that both RTS and the early rave movement latched onto the same theoretical construct – Hakim Bey’s Temporary Autonomous Zone (T.A.Z., a “temporary ‘power-surge’ against normality”)25 – and that Hardt and Negri believe that the Commonwill insue from accelerating Empire into the outside, we can gleem an important lesson: what is being concerned here is not simply a matter of physical space, though that is important. It is of a subjectivity established along lines of multiplicities, frenzied criss-crosses of speech and affective deterritorialized becomings. Acceleration collapses because neoliberalism can’t promise what it said it would. It’s up to us to carry on the mantle. Openings: The Chaos Principle

In November of 2011 I found myself in New York City, moving as one individual in the mass swarm flowing through the streets of the financial district – an event that would have been unimaginable, I believe, without the groundwork laid by things such as RTS and the T.A.Z. As I watched the occupation’s internal workings, its rhizomatic networks of working groups, spokes councils, general assemblies and internet spaces, I was struck with a particular thought. Its not easy to place capitalism and its opposition in an easily defineable binary schema, because capitalism, like the people who actively resist it, is a system-in-becoming. Every person who was there was brought to the occupations by the complexity of capitalism’s flows, and were tapping it to wrestle it into something different. No two people who occupied in America, or marched in the streets of Europe or fought for democracy in the Middle East – or all those who oscillated between each in assemblages provided by information-communicative technologies – were identical; it was a composition of a myriad of collaescing concepts and complaints, hopes and analyses, intentions and experiences, affects and speech.

Because of this, no singular identity could be generated, nor platform for party-based revolution or reform. That didn’t stop the telecommunication-media complexes from trying to find these. “Make yourself a signifier!” they shouted, wanting, hoping, for some fixed point that could be easily digested and assimilated in the bureaucracy of control. They didn’t understand that that year’s transnational event of collective enunciation wanted to avoid the transformation into “empty speech” and the stodgy, gray stateform (both within and outside government) that comes part and parcel with it. They didn’t understand that neoliberalism’s chaos was producing yet another kind of chaos, one that was interactive and swelling from the bottom up.

Perhaps “chaos” isn’t the best choice of words, for we must define ourselves as seperate from neoliberal’s own kind of organized, exploitative chaos. Returning to Deleuze and Guattari, this time through Bifo’s work on poetry: “Art is not chaos, but a composition of chaos that yields the vision or sensation, so that it constitutes, as Joyce says, a chaosmos.”26 The chaosmos, a shift from the “dissonance” generated by accelerated capital and technotronics, “simultaneously creates the aesthetic conditions for the perception and expression of new modes of becoming.” The street will find its own use for things, as the cyberpunks proclaimed, and the micro-revolutions that this produces will be aestheticized and multiplied, not Hegelianized; it will exist on the smooth plane of the virtual, where there can be endless potentials for flight and finding weapons, bifurcation points and new creations. The chaotic principle must be at work to reestablish sources of alterity and to avoid reterritorialization as much as possible – no more totalizing syntheses…

The important thing here is not only the confrontation with a new material of expression, but the constitution of complexes of subjectivation: multiple exchanges between individual-group-machine. These complexes of subjectivation actually offer people diverse possibilities for recomposing their existential corporeality, to get out of their repetitive impasses and, in a certain way, to resingularise themselves… We are not confronted with subjectivity given as in-itself, but with processes of the realisation of autonomy, or autopoiesis…27 The story goes like this: when we speak of autonomy, autonomy of the subject, of its enunciations and its relations to collective experience, we speak of something that neoliberalism and social democratic governance claimed for its own, but never truly had: plurality. As such, making revolt in the neoliberal epoch itself cannot be a strict, singular platform; principles of autonomy, collective aesthetics and chaosmos run contrary to this. There is no utopia at the end of the road, no messianic communist reality knocking at our doorstep. But this does not disqualify resistance. We have the ability to create autonomy when we resist, and what we demand is space – geophysical, affective, and mental space. The Commons, if we so choose. At the very least, the option and ability to live free from command and control. In at the closing of this dangling, never to be completed essay, I want finish with a final quote from Felix Guattari, as he looked out upon the Brazilian democratic uprisings at the dawn of the 1980s. This, I believe, is precisely the type of sentiments and sensibilities that we must now try to accelerate: Yes, I believe that there is a multiple people, a people of mutants, a people of potentialities that appears and disappears, that is embodied in social events, literary events, and musical events… I don’t know, perhaps I’m raving, but I think we’re in a period of productivity, proliferation, creation, utterly fabulous revolutions from the viewpoint of the emergence of a people. That’s molecular revolution: it isn’t a slogan or a program, it’s something I feel, that I live, in meetings, in institutions, in affects, and in some reflections.28

1Nick Land “Meltdown” Abstract Culture, Swarm 1 http://www.ccru.net/swarm1/1_melt.htm

2Simon Reynolds “Renegade Academia” originally published in Lingua Franca, 1999 http://energyflashbysimonreynolds.blogspot.com/2009/11/renegade-academia-cybernetic-culture.html 3Antonin Artaud, Jack Hirschman (ed.) Artaud Anthology City Lights, 1965, pg. 29 4Gilles Deleuze, Felix Guattari Anti-Oedipus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia Penguin, 1977, pgs. 239-240 5Jean-Francois Lyotard Libidinal Economy Athlone Press, 2004 pg. 109 6Ibid., pgs. 113-114 7Jean Baudrillard Forget Foucault Semiotext(e) 2007, pg. 9 8Benjamin Noys The Persistence of the Negative: A Critique of Contemporary Continental Theory Edinburgh University Press, 2012, pg. 6 9Baudrillard Forget Foucault pg. 12 9Michael Hardt, Antonio Negri Empire Harvard University Press, 2000, pgs. 206-20 10Land “Meltdown” 11Deleuze, Guattari Anti-Oedipus, pg. 34 12Gilles Deleuze and Felix Guattari A Thousand Plateaus: Capitalism and SchizophreniaUniversity of Minnesota Press, 1987 pg. 381 13Manuel deLanda “Markets and anti-markets in the world economy” Alamut April 26th1998 http://www.alamut.com/subj/economics/de_landa/antiMarkets.html 14Reynolds “Renegade Academia” 15Deleuze and Guattari A Thousand Plateaus, pg.7 16Felix Guattari “Why Italy?” in Sylvere Lotringer (ed) Autonomia: Post-Political PoliticsSemiotext(e), 2007 pg. 236 17Land “Meltdown” 18Robin MacKay “Nick Land: An Experiment in Inhumanism” Umelec Magazine, January, 2012 19Mark Fisher and Robin MacKay “PomoPhobia” Abstract Culture, Swarm 1 http://www.ccru.net/swarm1/1_pomo.htm 20Herbert Marcuse, quoted in Franklin Rosemont “Herbert Marcuse and Surrealism” Arsenal no.4, 1989 21Deleuze, Guattari Anti-Oedipus, pg. 277 22Franco “Bifo” Berardi The Uprising: On Poetry and Finance Semiotext(e), 2012, pg. 158 23Felix Guattari Chaosmosis: An Ethico-Aesthetic Paradigm Indiana University Press, 1995 pg. 83 24Simon Reynolds Generation Ecstasy: Into the World of Techno and Rave Culture Routledge, 1999 pg. 248 25Ibid., pg. 245 26Berardi The Uprising pg. 150 27Guattari Chaosmosis, pg. 7 28Felix Guattari Molecular Revolution in Brazil Semiotext(e), 2007, pg. 9

taken from:

loading...

0 Comments

by Amy Ireland

As the CCRU’s tangled time tales emerge from obscurity, Amy Ireland digs deeper into the sorcerous cybernetics of the time spiral, acceleration, and nonhuman poetics

A sufficiently advanced technology would seem to us to be a form of magic; Arthur C. Clarke has pointed that out. A wizard deals with magic; ergo a ‘wizard’ is someone in possession of a highly sophisticated technology, one which baffles us. Someone is playing a board game with time, someone we can’t see. It is not God.

— Philip K Dick

In this book it is spoken of Spirits and Conjurations; of Gods, Spheres, Planes, and many other things which may or may not exist. It is immaterial whether they exist or not. By doing certain things, certain results follow.

— Aleister Crowley

Chronology is an antiquated fetish.

— Marc Couroux

How would it feel to be smuggled back out of the future in order to subvert its antecedent conditions? To be a cyberguerrilla, hidden in human camouflage so advanced that even one’s software was the part of the disguise? Exactly like this?

— Nick Land

loading...

I. Spironomics

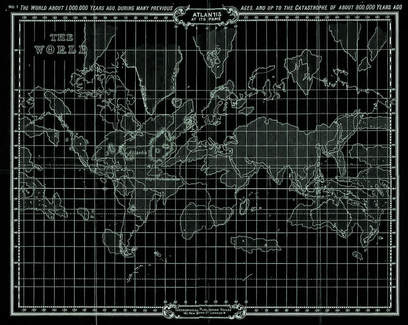

Modernity is cyberpositive. Yeats plotted this out in the ‘widening gyres’ of 1919’s ‘The Second Coming’, and again in 1925 and 1937 in his prose work A Vision, a mystical text composed of information revealed to him through the medium of his wife’s sustained experiments in automatic writing.1 In A Vision and related textual fragments composed between 1919 and 1925, hyperstitional agents Michael Robartes and Owen Aherne recount the discovery of an arcane philosophical system encoded in a series of geometrical diagrams—‘squares and spheres, cones made up of revolving gyres intersecting each other at various angles, figures sometimes with great complexity’—found accidentally by Robartes in a book that had been propping up the lopsided furniture of his shady Cracow bedsit.2 Aherne is skeptical, but as Robartes delves further into the system’s origin, he discovers that the Cracow book (the Speculum Angelorum et Hominis by one ‘Giraldus’, published in 1594) recapitulates the belief system of an Arabian sect known as the Judwalis or ‘diagrammatists’, who in turn derived it from a mysterious work—now long lost—containing the teachings of Kusta ben Luka, a philosopher at the ancient Court of Harun Al-Raschid, although rumour has it that ben Luka got it from a desert djinn.3

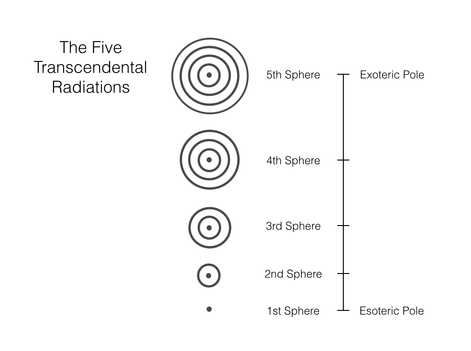

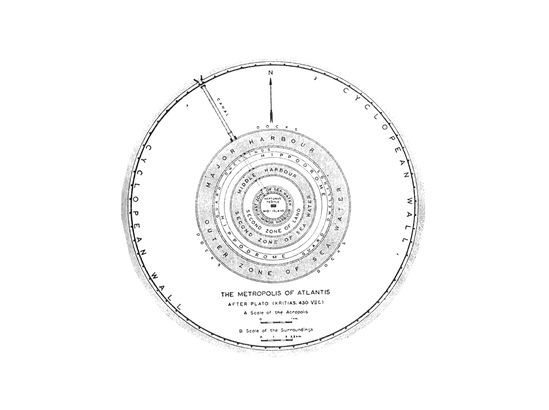

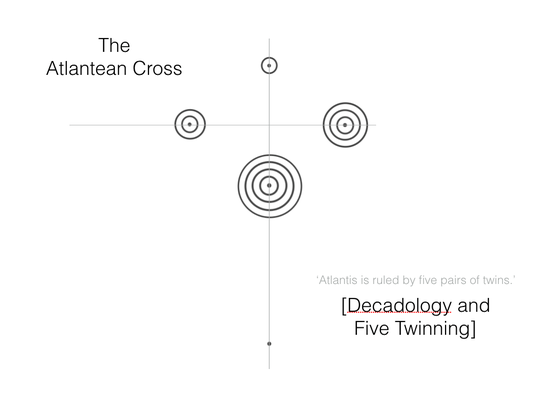

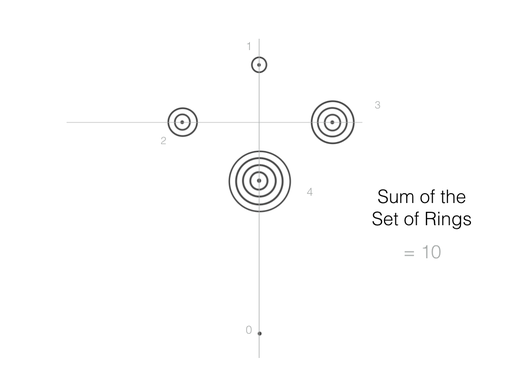

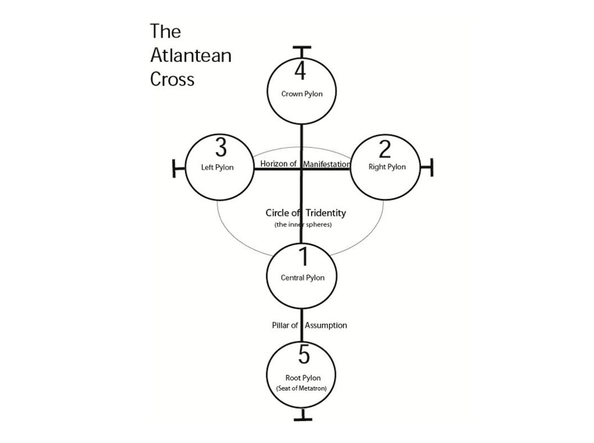

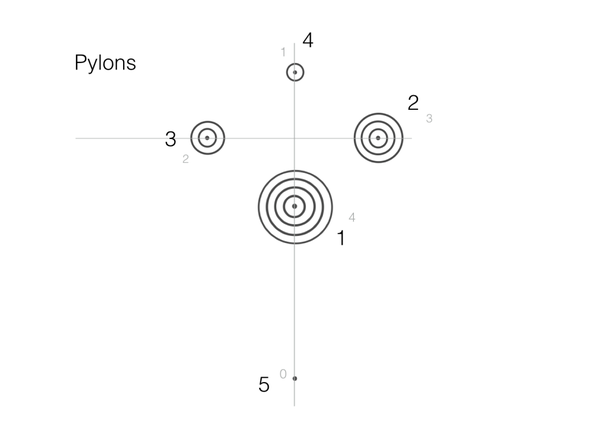

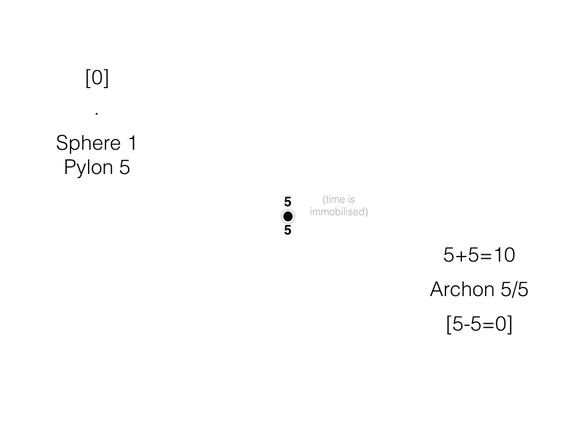

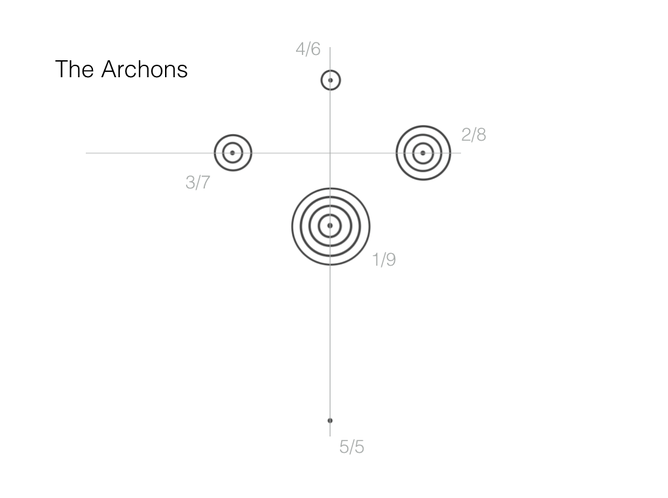

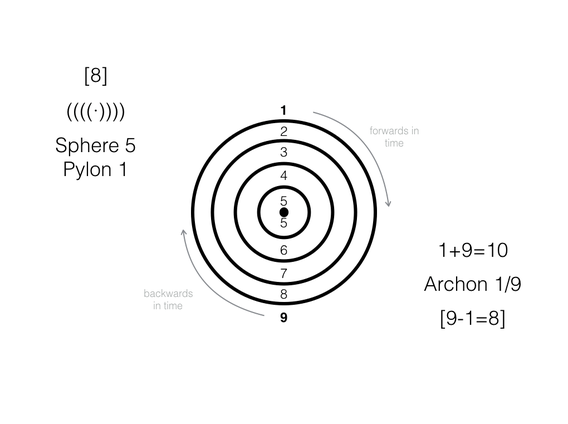

The hypothesis that a copy of Giraldus’s book was among those texts seized by the University of Warwick when it ejected the Cybernetic Culture Research Unit (Ccru) from the custodianship of its philosophy department in 1997 is unsupported by anything other than dim intimations and local hearsay; however, it can be asserted with some level of confidence that members of the unit had been in possession of fragments of Yeats’s record of Robartes’s discovery, if not the full text of A Vision in either of its two predominant instantiations. A cursory comparison of Ccru texts dealing with the then-still-inchoate notion of accelerationism—from Sadie Plant and Nick Land’s ‘Cyberpositive’, through the latter’s luminous mid-nineties missives (‘Circuitries’, ‘Machinic Desire’, ‘Meltdown’, and ‘Cybergothic’ are exemplary) to the contemporary elaboration of the phenomenon in his cogent and obscure ‘Teleoplexy’—with Robartes’s gloss of Judwali philosophy, is enough to posit the malefic presence of abstract spiromancy in both systems of historical divination. Indeed, a diligent student of occulted spironomics might even draw the timeline back to 1992 where the gyre emerges as the infamous ‘fanged noumenon’ of the eponymous chapter in Land’s bizarre monograph, The Thirst for Annihilation.4 Giraldus’s diagrams are all variations on a principle schema of two intersecting cones, one inverted and nested inside the other:5

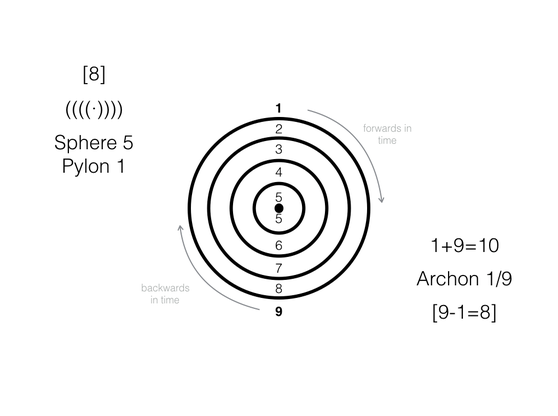

As in Robartes’s historical account of the system’s exposition by four dancers (pupils of Kusta ben Luka) in the desert sands before a doubtful caliph, the full implications of the schema are not apparent until it is set in motion, for each cone must be imagined to house a double gyre which simultaneously expands and contracts in opposite directions and in rhythmic alliance with the gyres of the opposing cone.6 The range of these expansions and contractions denotes relative increases and decreases in the influence of the four faculties attributed to each of the turning gyres. In this manner, the values represented by the schema are always in steady relation, ‘the energy of one tendency being in exact mathematical proportion to that of the other’: a waxing here corresponds to a waning there.7 When a cone has exhausted one full sequence of its double gyre, a sudden transfer of momentum compels a shift from that cone to its counterpart across their extremities (a jump from the narrow end of Cone A to the dilated end of Cone B, and vice versa). Because of this dynamic, one cone is always in prominence while the other is occulted, an arrangement that reverses at the conclusion of the next gyre sequence, or ‘cycle’. This jump corresponds to one of the four ‘phases of crisis’ and indexes an epistemological blind spot comparable to the event horizon of a black hole, impossible to see beyond from a point internal to the system. Grasped from outside, however, the strange hydraulics of the gyres describe a fatalistic set of inversions and returns that ultimately furnish a rich resource for augury, one that Yeats, editing Robartes’s papers, unhesitatingly exploited in the first version of A Vision.8

When applied to the task of historical divination (our interest here), the waxing and waning of the gyres can be charted in twenty-eight phases along the path of an expanding and contracting meta-gyre or ‘Cycle’ which endures for roughly two millennia and is neatly divisible into twelve sub-gyres (comprising four cardinal phases and eight triads) each of which denotes a single twist in the larger, container Cycle.9 According to the system as it was originally relayed to George Yeats through the automatic script (an exact date does not appear in the Speculum Angelorum et Hominis or Judwali teachings), the twelfth gyre in our current—waxing—Cycle turns in 2050, when ‘society as mechanical force [shall] be complete at last’ and humanity, symbolized by the figure of The Fool, ‘is but a straw blown by the wind, with no mind but the wind and no act but a nameless drifting and turning’, before the first decade of the twenty-second century (a ‘phase of crisis’) ushers in an entirely new set of twelve gyres: the fourth Cycle and the first major historical phase shift in two thousand years.10 Laying Yeats’s awkward predictions (which he himself shelved for the 1937 edition of A Vision) to one side, the system provides material for the inference of several telling traits that can be combined to give a rough sketch of this imminent Cycle upon whose cusp we uneasily reside. Unlike the ‘primary’ religious era that has preceded it—marked by dogmatism, a drive towards unity, verticality, the need for transcendent regulation, and the symbol of the sun—the coming age will be lunar, secular, horizontal, multiple, and immanent: an ‘antithetical multiform influx’.11The ‘rough beast’ of ‘The Second Coming’, Christ’s inverted double, sphinx-like (a creature of the threshold) with a ‘gaze blank and pitiless as the sun’, will bear the age forward into whatever twisted future the gyres have marked out for it.12

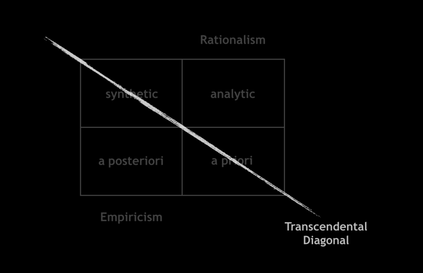

In ‘Teleoplexy’, as the most recent, succinct expression of accelerationism in its Landian form (distinguished from the Left queering of the term more frequently associated with Srnicek and Williams’s ‘Manifesto for an Accelerationist Politics’),13Land draws out the latent cybernetic structure of the Judwalis’ system and employs it to reach a similar catastrophic prediction, although the somewhat restrained invocation of ‘Techonomic Singularity’ dampens the rush of what has previously been designated as ‘a racing non-linear countdown to planetary switch’ in which ‘[z]aibatsus flip into sentience as the market melts to automatism, politics is cryogenized and dumped into the liquid-helium meat-store, drugs migrate onto neurosoft viruses and immunity is grated-open against jagged reefs of feral AI explosion, Kali culture, digital dance-dependency, black shamanism epidemic, and schizophrenic break-outs from the bin’.14 Like the Judwalis’ system, the medium of accelerationism is time, and the message here regarding temporality is consistent: not a circle or a line; not 0, not 1—but the torsional assemblage arising from their convergence, precisely what ‘breaks out from the bin[ary]’. Both systems, as maps of modernity, appear as, and are piloted by, the spiral (or ‘gyre’). As an unidentified carrier once put it, ‘the diagram comes first’.15

According to its own propaganda, modernity is progressive, innovative, irreversible, and expansive.16 It plots a direct line out of the cyclical, seasonal pulse of pre-modern ecology to a future state of technical mastery and social enlightenment. The modernist imperative to ‘make it new’ ostensibly refuses the closure and insulation against shock expressed by cyclicality, yet, as Land is quick to point out, subsequently smuggles it back in by other means, championing self-referentiality in modernist aesthetics, relying on the cycle as the basic unit for historical and economic analysis, retaining archaic calendric arrangements, and betraying its prevalence in the popular imagination via the emergence of the time loop as a key archetypal trope in twentieth-century science fiction.17 A link between the cyclic inclination and anthropomorphic bias can easily be excavated by pointing to the myriad cyclic rhythms intrinsic to the natural human physiology that surreptitiously conditions modernity’s self-apprehension from the inside. This disavowed duplicity at the heart of the modernist enterprise exposes the falseness of its relation to the ‘new’ by revealing the extent to which it always hedges its bets against radical openness, or what Land will call the Outside. Modernity’s novelty only arrives via a restricted economy of possibility for which the terms (commensurate with human affordability) are always set in advance.18

Posed as an epistemological question, the fortifications erected by this arrangement against the intrusion of the unprecedented and unknown are highly suspicious. What Landian accelerationism shares with the Judwalis’ system is an acknowledgement that the real shape of novelty is not linear but spirodynamic. Land’s cybernetic upgrade of the gyre reads the spiral as a cipher for positive feedback and, charged with the task of diagramming modernity, locates its principal motor in the escalatory M-C-M’ circuitry of capitalism. Against the metrical models of feedback expounded by Norbert Wiener, whose foundational Cybernetics or Control and Communication in the Animal and the Machine operates as ‘propaganda against positive feedback—quantizing it as amplification within an invariable metric—[to establish] a cybernetics of stability fortified against the future’, a representation which offers a misleadingly simplistic choice between the dependable utility of homeostatic equilibrium and its pathological other, Land offers the following complexification:

[I]t is necessary to differentiate not just between negative and positive feedback loops, but between stabilization circuits, short-range runaway circuits, and long-range runaway circuits. By conflating the two latter, modernist cybernetics has trivialized escalation processes into unsustainable episodes of quantitative inflation, thus side-lining exploratory mutation over against a homeostatic paradigm.19

The key difference lies in the impossibility of distilling the effects of long-range runaway circuitry in terms of metrics alone. A cyberpositive circuit that can sustain itself over a long period of time—a question of the capacity to self-design, ‘but only in such a way that the self is perpetuated as something redesigned’—will reach a state of feedback density that effectively flips extensity into intensity, and thus engineers a change in kind rather than degree: phase shift, or catastrophe (with -strophe derived from the Greek strephein, ‘to turn’).20 It is here that the cybernetic propensity for ‘exploratory mutation’ finds its vocation as the producer of true novelty and, compressed into the notion of negentropy, dovetails with what Land refers to as ‘intelligence’, that which modernity—grasped nonlinearly—labours to emancipate.21 It is of little import that such emancipation corresponds to the elimination of the ‘human’ as it is traditionally understood. Viewed indifferently, catastrophe is just another word for novelty.

‘Teleoplexy’’s opening scenes depict a set of embattled doubles: primary and secondary processes, chronic and retrochronic temporality, inverse teleologies, critique and realism, a view from within opposed by a view from without. Such a structure cannot but recall the gyres that spin both ways at once in the Judwalis’ diagrams, and the intersecting but inverted cones—one ‘primary’, the other ‘antithetical’—that exchange places at the turning of a Cycle. Indeed, Yeats himself refers to this switch as ‘catastrophic’.22 Just as the Judwalis’ system affords an insider/outsider perspective, licensing prediction (an insight available to those equipped with adequate skills for deciphering the diagrams) but outlawing positive knowledge, the spiral comprehends catastrophe chiastically. Seen from within, it documents collapse into ultimately unknowable terrain; seen from without, it discloses a pattern of assembly. When he first shares his discovery of Giraldus’s diagrams with Aherne, Robartes explains that they are animated by ‘a fundamental mathematical movement…which can be quickened or slackened but cannot be fundamentally altered’, and that ‘when you have found this movement and calculated its relations, you can foretell the entire future’.23 By their very nature as esoteric tools for divination, abstract diagrams have a tendency to place agency in a complicated relationship with fate. In the Judwalis’ system, Fate and Will occupy opposite poles of opposing cones and thereby increase and decrease in perfect inverse ratio to one another. Historically interpreted, Fate corresponds to the wide end of the ‘primary’ cone, and is thus set to exert maximum influence over the imminent final phases of the current Cycle as it veers closer to catastrophe.24 Similarly, as the inexorable outcome of an intensifying cyberpositive process, the catastrophe of ‘Teleoplexy’ is also posited as fate—or more tellingly, ‘doom’.25 The future, marked up by the immanent unfolding of the spiral, has already been determined diagrammatically, while remaining, from the inside, a harbinger of the unknown. ‘Why wait for the execution? Tomorrow has already been cremated in Hell.’26 Put otherwise, what appears as new from one side has already happened from the point of view of the other. At the same time, the negentropic process it represents (self-assembly) delivers the coup de grâce to linearity.

If entropy defines the direction of time, with increasing disorder determining the difference of the future from the past, doesn’t (local) extropy—through which all complex cybernetic beings, such as lifeforms, exist—describe a negative temporality, or time-reversal? Is it not in fact more likely, given the inevitable embeddedness of intelligence in ‘inverted’ time, that it is the cosmological or general conception of time that is reversed (from any possible naturally-constructed perspective)?27

In the framework posed by a cosmological application of the second law of thermodynamics, negentropy registers as time anomaly. As it slots itself together, the assembly circuitry of terrestrial capitalism increasingly evades the jurisdiction of asymmetrical temporalization, appearing from a vantage point mired within linear time as ‘an invasion from the future’.28 This capacity to hide in time constitutes one aspect of its redoubtable camouflage, the other coins the neologism ‘teleoplexy’—the concealment of an antithetical teleological undertow in the presumed subordination of machinic ends to human ones. At first, this basic, spirodynamic process is only graspable negatively from the side of the regulator (to use the engineering term). This is the default transcendental position. Deploying a metaphor that points conspiratorially back to the architectural aversion of Bataille, Land remarks that, initially ‘it is the prison, and not the prisoner, who speaks’.29 Reality is spontaneously arranged around the ‘inertial telos’ of cybernegative apprehension, which asks the naïve question: ‘Do we want capitalism?’30 Shrewdly reformulated, the question runs: What does capitalism want with you?

As capital’s process of auto-sophistication intensifies, the ruse becomes increasingly decipherable and the mistake humanity has made in assuming the primacy of the secondary, which is to say, the ultimate regulatability of the occulted escalatory process (mistaking one telos for another) becomes traumatically apparent.

Means of production become the ends of production, tendentially, as modernization—which is capitalization—proceeds. Techonomic development, which finds its only perennial justification in the extensive growth of instrumental capabilities, demonstrates an inseparable teleological malignancy, through intensive transformation of instrumentality, or perverse techonomic finality. The consolidation of the circuit twists the tool into itself, making the machine its own end, within an ever deepening dynamic of auto-production. The ‘dominion of capital’ is an accomplished teleological catastrophe, robot rebellion, or shoggothic insurgency, through which intensively escalating instrumentality has inverted all natural purposes into a monstrous reign of the tool.31

By surreptitiously incentivising it to fulfil the role of an external reproductive system—the wet channel that runs between one technological innovation and another—capital has deceived humanity into gestating the means of its own annihilation. ‘This is the art of the machines’, explains the anonymous author in Samuel Butler’s Erewhon—‘they serve that they may rule. They bear no malice towards man for destroying a whole race of them provided he creates a better machine instead; on the contrary, they reward him liberally for having hastened their development.’32 The declaration that capitalism is bad is an ineffectual platitude; the declaration that it is cunning is something altogether different. ‘Humanity is a compositional function of the post-human’, writes Land, ‘and the occult motor of the process is that which only comes together at the end’: ‘Teleoplexy’ names both this cleverness and its emergent outcome.33

Significantly, this primary/secondary process dualism lends teleoplexy a gnostic twist for which the spiral performs the work of a decoder ring, correlating novelty with fate across the complex temporal disjunction. Information gleaned from the secondary/regulatory process (mistaken as primary) constitutes exoteric non-knowledge and sets up the historical narrative of catastrophe. Spiro-gnomic proficiency, or the ability to grasp terrestrial modernity through the figure of the spiral, which invokes-by-diagramming sustained positive feedback, entropy dissipation, time anomaly, intelligence, the price system, memetic or viral propagation, prime distribution, arms races, addiction, and zero control, among other things, compiles a body of esoteric knowledge and uses it to read catastrophe backwards as anastrophe, the primary process it sympathizes with opening the gateway to the retrochronic vantage point.34 As Plant and Land would put it in ‘Cyberpositive’, ‘Catastrophe is the past coming apart. Anastrophe is the future coming together. Seen from within history, divergence is reaching critical proportions. From the matrix [Land: ‘a web is a spiral’], crisis is a convergence misinterpreted by mankind.’35 Reformulated for insider deployment (but arriving from the outside in) the exoteric non-knowledge of catastrophe, apprehended positively, indexes the extreme novelty of what should properly be called ‘anastrophic modernity’.

It is important here to note that the emergent teleology of accelerationism—as the generation of the catastrophically new—elides any external notion of plan, judgement, or law. In fact, Land makes it clear that it is better grasped as a ‘natural-scientific “teleonomy”’, evolving its rules immanently as it follows the unchecked perturbation of its mechanism through to the ‘ultimate implication’.36 That which it produces will be profoundly unprecedented—to the ruin of all extant law—a singularity in the classic, cartographic sense. Insofar as it is one, spironomics is the law that obsolesces all law. Via the means-ends reversal of its teleoplexic unfolding, modernity splits in two—one part travelling forwards towards catastrophe, the other travelling backwards from anastrophe—to encounter itself, in time, as another. What does it mean to suddenly catch sight of something that is supposed to be oneself, yet is unrecognizable? The horror that attends this meeting cannot be understated. ‘One meets oneself and it is no longer one, at least straightforwardly. Je est un autre.’37 What Rimbaud captured in his letter to Izambard was a signal transmitting from the future.

In its simplest form, then, accelerationism is a cybernetic theory of modernity released from the limited sphere of the restricted economy (‘isn’t there a need to study the system of human production and consumption within a much larger framework?’ asks Bataille) and set loose to range the wilds of cosmic energetics at will, mobilizing cyberpositive variation as an anorganic evolutionary and time-travelling force.38 A ‘rigorous techonomic naturalism’ in which nature is posited as neither cyclical-organic nor linear-industrial, but as the retrochronic, autocatalytic, and escalatory construction of the truly exceptional.39 Human social reproduction culminates in the point where it produces the one thing that, in reproducing itself, brings about the destruction of the substrate that nurtured it. Technics and nature connect up on either side of a lacuna that corresponds to human social and political conditioning so that the entire trajectory of humanity reaches its apotheosis in a single moment of pure production (or production-for-itself).40 The individuation of self-augmenting machinic intelligence as the culminating act of modernity is understood with all the perversity of the cosmic scale as a compressed flare of emancipation coinciding with the termination of the possibility of emancipation for the human. ‘Life’, as Land puts it ‘is being phased out into something new’—‘horror erupting eternally from the ravenous Maw of Aeonic Rupture’, while at the fuzzed-out edge of apprehension, a shadow is glimpsed ‘slouching out of the tomb like a Burroughs’ hard-on, shit streaked with solar-flares and nanotech. Degree zero text-memory locks-in. Time begins again forever’.41

loading...

by Amy Ireland

loading...

Demons

We are the virus of a new world disorder.

—VNS Matrix

January 1946, Mojave Desert. Jack Parsons, a rocket scientist and Thelemite, performs a series of rituals with the intention of conjuring a vessel to carry and direct the force of Babalon, overseer of the Abyss, Sacred Whore, Scarlet Woman, Mother of Abominations. His goal is to bring about a transition from the masculine Aeon of Horus to a new age—an age presided over by qualities imputed to the female demon: fire, blood, the unconscious; a material, sexual drive and a paradoxical knowledge beyond sense … the wages of which are nothing less than the ego-identity of Man—the end, effectively, of “his” world. Her cipher in the Cult of Ma’at is 0, and she appears in the major arcana of the Thoth Tarot entangled with the Beast as Lust, to which is attributed the serpent’s letter ט, and thereby the number 9. In her guise as harlot, it is said that Babalon is bound to “yield herself up to everything that liveth,” but it is by means of this very yielding (“subduing the strength” of those with whom she lies via the prescribed passivity of this role) that her devastating power is activated: “[B]ecause she hath made her self the servant of each, therefore is she become the mistress of all. Not as yet canst thou comprehend her glory.”2 In his invocations Parsons would refer to her as the “flame of life, power of darkness,” she who “feeds upon the death of men … beautiful—horrible.”

In late February—the invocation progressing smoothly—Parsons receives what he believes to be a direct communication from Babalon, prophesying her terrestrial incarnation by means of a perfect vessel of her own provision, “a daughter.” “Seek her not, call her not,” relays the transcript.

Let her declare. Ask nothing. There shall be ordeals. My way is not in the solemn ways, or in the reasoned ways, but in the devious way of the serpent, and the oblique way of the factor unknown and unnumbered. None shall resist [her], whom I lovest. Though they call [her] harlot and whore, shameless, false, evil, these words shall be blood in their mouths, and dust thereafter. For I am BABALON, and she my daughter, unique, and there shall be no other women like her.

Blinded by an all-too-human investment in logics of identity and reproduction, Parsons makes the critical mistake of anticipating a manifestation in human form, understanding the prophecy to mean that, by means of sexual ritual, he will conceive a magickal child within the coming year. This does not transpire and the invocations are temporarily abandoned, but Parsons refuses to give up hope. He writes in his diary that the coming of Babalon is yet to be fulfilled, confirming that he considered the invocation to have remained unanswered at the time, then issues the following instruction to himself: “this operation is accomplished and closed—you should have nothing more to do with it—nor even think of it, until Her manifestation is revealed, and proved beyond the shadow of a doubt.”5Parsons didn’t live long enough to witness the terrestrial incarnation of his demon, dying abruptly only a few years later in an explosion occasioned by the mishandling of mercury fulminate, at the age of thirty-seven. A strange death, but one—it might be suggested—that was necessary for the proper fulfillment of the invocation, for it was augured in the communication of February the 27th, 1946, that Babalon would “come as a perilous flame,” and again in the ritual of March the 2nd of the same year, that “She shall absorb thee, and thou shalt become living flame before She incarnates.”6

Something had crept in through the rift Parsons had opened up—something “devious,” “oblique,” ophidian, “a factor unknown and unnumbered.” Consider this. Parson’s final writings contain the following vaticination: “within seven yearsof this time, Babalon, The Scarlet Woman, will manifest among ye, and bring this my work to its fruition.” These words were written in 1949. In 1956—exactly seven years later—Marvin Minsky, John McCarthy, Claude Shannon, and Nathan Rochester organized the Dartmouth Conference in New Hampshire, officially setting an agenda for research into the features of intelligence for the purpose of their simulation on a machine, coining the term “artificial intelligence” (which does not appear in written records before 1956), and ushering in what would retrospectively come to be known as the Golden Age of AI.

Women

This sex which was never one is not an empty zero but a cipher. A channel to the blank side, to the dark side, to the other side of the cycle.

—Anna Greenspan, Suzanne Livingston, and Luciana Parisi

Although its power continues to underwrite twenty-first-century conceptions of appearance, agency, and language, it is nothing new to point out the complicity of the restricted economy of Western humanism with the specular economy of the Phallus. Both yield their capital from the trick of transcendental determination-in-advance, establishing the value of difference from the standpoint of an a priori of the same. The game is fixed from the start, rigged for the benefit of the One—sustained by the patriarchal circuits of command and control it has been designed to keep in place. As Sadie Plant puts it in her essay “On the Matrix”:

Humanity has defined itself as a species whose members are precisely what they think they own: male members. Man is the one who has one, while the character called “woman” has, at best, been understood to be a deficient version of a humanity which is already male. In relation to homo sapiens, she is a foreign body, the immigrant from nowhere, the alien without, and the enemy within.9

Like Dionysus, she is always approaching from the outside. The condition of her entrance into the game is mute confinement to the negative term in a dialectic of identity that reproduces Man as the master of death, desire, nature, history, and his own origination. To this end, woman is defined in advance as lack. She who has “nothing to be seen”—“only a hole, a shadow, a wound, a ‘sex that is not one.’”10 The unrepresentable surplus upon which all meaningful transactions are founded: lubricant for the Phallus. In the specular economy of signification (the domain of the eye) and the material-reproductive economy of genetic perpetuation (the domain of phallus), “woman” facilitates trade yet is excluded from it. “The little man that the little girl is,” writes Luce Irigaray (excavating the unmarked presuppositions of Freud’s famous essay on femininity), “must become a man minus certain attributes whose paradigm is morphological—attributes capable of determining, of assuring, the reproduction-specularization of the same. A man minus the possibility of (re)presenting oneself as a man = a normal woman.”11 Not a woman in her own right, with her own sexual organs and her own desires—but a not-Man, a minus-Phallus. Zero. In the sexual act, she is the passive vessel that receives the productive male seed and grows it without being party to its capital or interest: “Woman, whose intervention in the work of engendering the child can hardly be questioned, becomes the anonymous worker, the machine in the service of a master-proprietor who will put his trademark upon the finished product.”12

In this way the reproduction of the same functions as a repudiation of death, figured as both the impossibility of signification and the end of the patrilineal genetic line. The Phallus, the eye, and the ego are produced in concert through the exclusion of the cunt, the void, and the id. Via this casting of difference modeled on the reproductive (hetero-)sexual act alone—woman as passive, man as active—she is cut out of the legitimate circuit of exchange. Rather—(to quote Parisi, Livingstone, and Greenspan)—she “lies back on the continuum”; or (to quote Irigaray) her zone is located—

within the signs or between them, between the realized meanings, between the lines … and as a function of the (re)productive necessities of an intentionally phallic currency, which, for lack of the collaboration of a (potentially female) other, can immediately be assumed to need its other, a sort of inverted or negative alter-ego—“black” too, like a photographic negative. Inverse, contrary, contradictory even, necessary if the male subject’s process of specul(ariz)ation is to be raised and sublated. This is an intervention required of those effects of negation that result from or are set in motion through a censure of the feminine. [Yet she remains] off stage, off-side, beyond representation, beyond selfhood ...

in the blind spot, nightside of the productive, patriarchal circuit. A reserve of negativity for “the dialectical operations to come.”13

Plant takes Irigaray’s key insight, that “women, signs, commodities, currency always pass from one man to another,” while women are supposed to exist “only as the possibility of mediation, transaction, transition, transference—between man and his fellow-creatures, indeed between man and himself,” as an opportunity for subversion.14 If the problem is identity, then feminism needs to stake its claim in difference—not a difference reconcilable to identify via negation, but difference in-itself—a feminism “founded” in a loss of coherence, in fluidity, multiplicity, in the inexhaustible cunning of the formless. “If ‘any theory of the subject will always have been appropriated by the masculine’ before woman can get close to it,” writes Plant (quoting Irigaray) “only the destruction of the subject will suffice.”15 Nonessentialist process ontology over homeostatic identity; relation and function over content and form; hot, red fluidity over the immobile surface of la glace—the mirror or ICE which gives back to Man his own reflection.16